Rotator Cuff Tear

advertisement

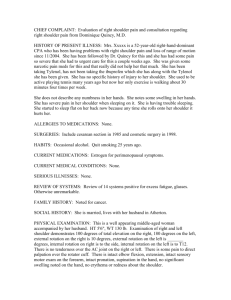

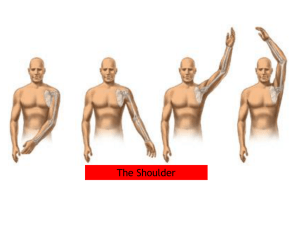

Rotator Cuff Tear Case Study: Carrie is a 62 year old secretary who enjoys tennis and golf during her time off from work. Carrie presents for an initial evaluation with severe pain and loss of function of her right shoulder. She explains that she felt her shoulder "give out with serious pain" during the downward motion of her tennis serve. The patient reports that she had to immediately take a break from tennis that day due to the pain. Carrie reports that she could not sleep at all the night after the injury and woke up with her arm "stuck" at her side. The patient presents with subjective pain 9/10 on the NPRS when attempting to lift her arm from her side and when she is trying to relax in bed. The patient also presents with trace muscle activation (1/5 MMT) in right shoulder flexion, abduction and external rotation with her arm at her side. Carrie did not go to an orthopedic surgeon and did not have imaging done to confirm a diagnosis. The patient is currently limited by pain in all shoulder and scapular movements that would allow for special testing to be done. Pathophysiology: Chronic overuse of the glenohumeral complex can lead to erosion of the connective tissue of the rotator cuff muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis). Rotator cuff tears are often associated with overhead motion which chronically impinges the infraspinatus and supraspinatus tendons. Chronic impingement of the rotator cuff complex initially presents with weakness in glenohumeral external rotation and abduction as the supraspinatus aides in shoulder elevation within the initial 60 degrees of range. Symptoms of an overuse rotator cuff tear include (but are not limited to): * Impaired active range of motion secondary to tendonous lesion * Severe subjective pain * Difficulty letting the affected upper extremity hang at one's side * Difficulty sleeping through the night * Difficulty carrying heavy objects * Weakness in active glenohumeral flexion, abduction, and external rotation * Difficulty with bathing and dressing (donning/doffing a bra) * Difficulty with activities of daily living related to glenohumeral function Treatment: A patient with suspected rotator cuff tear will typically present to Physical Therapy with complaints of severe pain with flexion and abduction of the GH joint. A patient with suspected rotator cuff tear must regain functional AROM within the first 6-8 weeks after injury. Failure to regain functional active range of motion and/or passive range of motion within this time period may result in adhesive capsulitis of the glenohumeral joint. Adhesive capsulitis of the glenohumeral joint can arise from a variety of factors including: * Overuse * Trauma * Diabetes Mellitus I and II * Surgical error * Hypothyroidism * Postural abnormality Along with regaining active range of motion in the injured glenohumeral joint, it is vital to regain functional motor control of the surrounding active tissues. Without proper motor control and strength of the intact structures, biomechanical faults may lead to further injury and joint restriction. The entire shoulder complex must be assessed when treating a rotator cuff injury. Scapulothoracic biomechanics, glenohumeral roll and glide, and sternoclavicular/acromioclavicular mobility all equate to proper upper quarter function. Special Test Sequence for Assessing Upper Quarter Dysfunction: Credit: Jason Myerson MPT, PT, OCS, FAAOMPT, DMT * Patient seated * Passive Neer Test * Passive Hawkin's Kennedy * Active Empty Can * Evaluate Scapular mobility * Stabilize scapula in retraction and depression and re-assess glenohumeral mobility Passive range of motion is initially introduced once the patient's subjective pain level is under control. Passive progressions include: * Supine PNF patterns in D1/D2 * Side lying scapular PNF in D1/D2 * Supine passive glenohumeral flexion/scaption/abduction/IR/ER Once functional passive range of motion is achieved, the patient is introduced to active assisted range of motion (AAROM) to begin the process of achieving functional motor control. AAROM should begin in a gravity assisted position to assist in achieving improved range through the movement. Active assisted range of motion aides in glenohumeral mobilization with an emphasis on an introduction in proper motor control strategies of surrounding contractile tissue. Non-contractile tissue also benefits from both the active and passive components of this type of movement through mild stress and synovial lubrication of the joint. When instructing a patient on proper form when performing AAROM techniques, it is very important to address scapular mobility to allow for full, healthy motion. AAROM is performed until the patient has achieved functional range using an external assistive force. Once this is achieved, active range of motion progressions should be introduced. Active range of motion (AROM) should begin in a gravity-eliminated position. Gravity's influence on the involved extremity can add resistance to the movement, not allowing for a proper progression. In the case of the glenohumeral joint, supine and side lying are advantageous positions to begin flexion, abduction, and rotational activity. Achieving functional AROM in the injured glenohumeral joint is a difficult task, The keys to maximizing treatment effects when dealing with a rotator cuff injury include: * Decreasing subjective pain level * Improving the patient's ability to sleep through the night * Achieving full PROM immediately * Avoiding tasks and movements that stress healing tissue * Achieve full AAROM with gravity and external assistance (i.e. table slide/wall slide) * Achieve functional AROM of the glenohumeral joint * Achieve functional MMT of the intact shoulder girdle musculature.