Educational Services for Students with Vision Loss in Canada

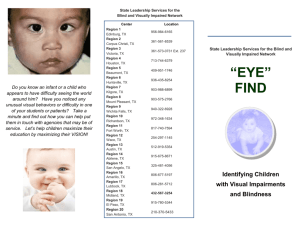

advertisement