Producing Accessible Publications

advertisement

First Steps in Producing

Accessible Publications

July 2005

Contents

Foreword

5

Introduction

6

Context of this Guide

6

Single Source Publishing

6

Clear Print in Principle

7

Typeface

7

Type size

8

Type weight

8

Type style

8

Leading

8

Numbers

9

Line length

9

Word spacing and alignment

9

Bullet lists and tabs

10

Design and layout

10

Contrast

10

Reversing type (white text on black background)

11

Navigational aids

11

Images

11

Columns

12

Paper

12

Clear Print in Practice

13

Putting Clear Print into Practice

13

Clear Print in Production

14

MS Word

15

Large Print

15

Process

16

Non-textual Contents

16

Alternative

17

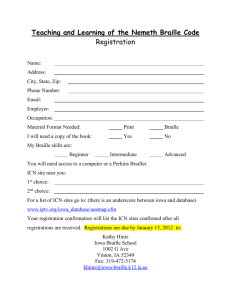

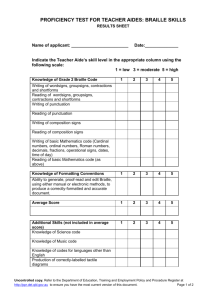

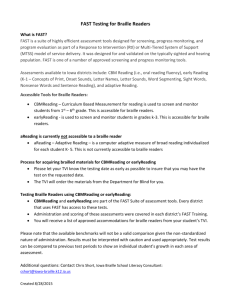

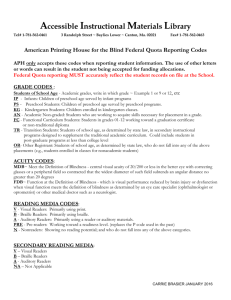

Braille

17

Process

17

Procedures

17

Timing

18

Costs

18

Resources

19

Audio: Cassette or CD-ROM

20

Process

20

Recording Medium

21

Visual to Aural

21

Additional and Non-textual Contents

22

Labelling

22

Post Production

23

Future of Audio format

23

Costs

23

Resources

24

Electronic Formats

24

HTML

24

PDF

29

CD-ROM

32

Standard Print Publication

32

Extras Covers or Inserts

33

Additional services

33

Bibliography

34

Foreword

Publication is one important and useful method of communicating information to an

audience. In much of our everyday lives - in education, business, consumer services- the

information available that we need to live and participate fully in our society is presented in

standard paper publications. While these are accessible to many people they exclude many

others, who cannot access the information within. The solution is simple - providing

publications in a choice of formats, so that each member of the audience can select one that

suits them best, allows greater access to the information and ensures messages are more

effectively communicated.

In producing this booklet the National Disability Authority has two core aims. First, to assist

those involved in producing publications to explore the need and opportunity to produce their

publications in a range of formats to meet the diverse needs of their intended audience. The

second aim is to provide basic information on how to produce these various formats. The

booklet is not intended as a comprehensive guide to creating accessible publications, but it

outlines many of the ‘first steps’ and directs the user towards sources of additional

information. Advances in technology mean that some of the information offered will

inevitably become dated, as the range of options available to those who wish to

communicate information becomes even greater.

The information and advice offered here are drawn from a number of sources, including the

National Disability Authority’s own experience of producing publications in different formats,

and from consultation with people who require different publication formats to meet their

needs. The document is available in standard document, large print, and Braille printed

versions, audio cassette, audio CD; HTML, PDF, electronic word and CD-ROM formats.

The NDA hopes that this will be a useful tool for all those who seek to communicate with an

audience, and will promote the use of a range of formats so that more people will be able to

access information in a format that suits them.

Angela Kerins

Chairperson, National Disability Authority

Introduction

Understanding the needs of your audience is critical to getting your message across. When creating

documents for a wide ranging audience, it is good practice to consider the various needs and

requirements of your audience and then to construct and design the content to best suit those

needs.

This publication will examine good practices for single source publishing – that is creating various

formats from one master copy. This will help to reduce the time and cost involved with the

production process. In doing so, the authors need to understand and adopt the ‘clear print’

procedures and to consider the style and design when planning the creation of an accessible-ready

master copy.

Context of this Guide

This guide will provide a simple understanding on how to maximise efficiency when creating a single

master document for the production of multiple accessible formats. It will examine good practices

associated with producing documents in Word, large print, Braille, audio CD/cassettes, HTML, PDF,

CD-ROM and the standard print publication. These procedures are intended to assist with the

preparation of the document. Some of the formats may require a multi-step conversion process

before they are fully accessible.

Single Source Publishing

Single source publishing is an approach in which one master document is formatted in such a way

as to allow the production of the document in other formats. It is essential that the planning phase of

the document be considered in depth. The author or project manager must identify all possible

audiences of the document, determine the different types of formats required and consider the

timing and costs involved. For example, MS Word and HTML are very popular electronic formats for

people who use assistive technology and software such as screen readers and magnifiers to access

documents. Examples of such software include JAWS, Windows Eyes, Supernova Reader

Magnifier, Zoomtext and Kurzweil. For Braille readers, a Braille document may be the preferred

medium. Some people with visual impairment may prefer large print, audio CD or cassette.

The key to successful single source publishing is the production of a ‘clear print’ document using

good practices for accessibility. Adopting these recommendations will assist the production of other

formats such as HTML, PDF, large print, Braille and audio.

Clear print is an approach to the design and production of printed materials which takes into

consideration the needs of readers who are blind, partially sighted or who have other special

needs. The following recommendations are straightforward, practical and inexpensive. They

focus on font, type size, contrast, and page navigation. These recommendations are based

on NCBI’s suggestions and the RNIB’s See It Right Pack.

Clear Print in Principle

Typeface

Typeface refers to a group of characters with the same properties and appearances. In

addition to the upper and lower case options, it also includes punctuation, numbers and

symbols.

There are two general categories of typefaces: san serif and serif. Serif typefaces have little

‘feet’ (serifs) at the end of the letters. San serif typefaces do not.

For example: Gils Sans is a san serif font and Times New Roman is a serif font.

Both typefaces are used in publications. However, according to the NCBI, san serif fonts are

preferred. Arial, Helvetica, and Gill Sans are some of the more popular sans serif choices.

Choose a clear, easy-to-read typeface for your document.

Typefaces to avoid are the highly stylised ones such as the ornamental or display typefaces

shown here.

Algerian

Bauhaus

Castellar

Harlow Solid Italics

Type size

The size of the type also known as point size is one of the two most important features when

producing ‘clear print’ documents. ‘Clear print’ documents should use a minimum type size of 12.

Size 14 is a preferred size so that some people with visual impairment can access the standard

format. The most commonly used large print size is 18.

Type weight

Typefaces are usually available in light, normal (Roman), semi-bold (medium) or bold weights. Light

options should be avoided as bolder typefaces are easier to read. If necessary use bold for

emphasis rather than UPPER CASE or italics.

Type style

Text which is set in italics or capitals is usually more difficult to read. For this reason, capital letters

in words, titles and the body of the text should be avoided whenever possible. If necessary, they

may be used to give emphasis to a single word or phase but not to the entire block of text.

Italics should be avoided. Instead, use a different type weight to emphasise the text.

Underlining should also be avoided since it makes the letters harder to recognise.

Leading

Leading refers to the space between one line of type and the next. The space between one line and

the next should be at least 1.5 times the space between words on a line.

This 13 points Helvetica text has very tight leading which can

make reading more difficult. This is set on 12 points leading.

It is harder to read words that are spaced closely to each

other.

This 13 points Helvetica text is set on 14 points leading which

is common for type at this size.

This 13 points Helvetica is set on 18 points leading which is

generous for the font size and helps to create an open,

inviting document.

Numbers

If your document includes numbers, it is important to choose a font that distinctly portrays the

numbers. The numbers 3, 5, 6, 8 and 0, may easily be misread and may cause added difficulty for

people with visual impairments. To avoid confusion, wherever possible, write out the word ‘five’ or

‘eight’ instead of the numeral. Some typefaces have clearer numerals than others. Here are some

examples:

1234567890

1234567890

It is advisable to use clear and consistent page numbering throughout your document.

Line length

Line length should be between 60-70 characters per line. Lines that are too long or too short may

tire the eyes. The same applies to sentence and paragraph lengths.

Splitting words by using hyphens disrupts the flow of the text and should be kept to a minimum.

However, if it is not possible to completely omit the use of hyphens in a report, the inclusion of one

or two hyphenated words within a block of text is acceptable.

Word spacing and alignment

It is best to keep the same amount of space between each word. Do not condense or stretch lines

of type to fit your line length since this reduces legibility.

Word spacing refers to the way in which text is aligned – left, right, justified or centred. In left

aligned text, it is easy to find the start and finish of each line and even spaces exist between the

words.

Justified text, which is aligned both left and right, may be easily read if the space between the

words is consistent. However, this is difficult to achieve with most desktop publishing software. It is

therefore best avoided as it can result in stretched or crammed lines of text.

Right alignment of text produces a ragged left margin that may be problematic for people with visual

impairment. Each new line starts in a different place and is therefore difficult to find.

Centred text where each line begins and ends differently may be even more difficult to read. It

should be avoided for blocks of text. It is acceptable for use in titles or headings.

Line spacing should be even. Continuous paragraphs should not be widely spaced. Initials or

words should not be divided or split across a line break. Text should be set horizontally. Text that

is set at an angle or on a curved line is more difficult to follow. Text set vertically is extremely

difficult to read and should not be used.

Bullet lists and tabulations (tabs)

It is advisable to present information in a list rather than using a column or table format. When

creating bullet lists, define and create the bullet style in the style sheet of the document. It is also

advisable to pre-set all tabs in the document so that it is consistent. Avoid using the space bar for

tabs and indentations. Set the tab style and start with a minimum of 0.5cm and indent at equal

increments such as every 0.5cm so that the next tab will be set at 1.0cm, 1.5cm, etc. This could all

be pre-set in the style sheet.

Design and layout

User-friendly design is simple and uncluttered. The elements of a page layout - headings,

photographs, illustrations, text, captions, tables, etc. – should be clearly separated from other

sections.

Contrast

The contrast between text and the background on which it is printed or photocopied is extremely

important. People with visual impairment frequently have difficulty with colour perception. Hence

two colours that are sharply contrasting to an individual without visual impairment such as green

and red, will appear far less distinguishable to someone with partial sight.

Contrast is affected by several factors including paper colour, printing ink, lighting and the size and

weight of the type. The relationship between colours is more important than the colours

themselves. As a general rule, contrast dark against light.

Reversing type (white text on black background)

If using white type, make sure that the background is dark enough to provide sufficient contrast.

Some people prefer a darker background because it reduces the amount of glare from the paper.

However, from a publishing perspective, it is virtually impossible to produce good quality white text

on a dark background.

The size and weight of the type is also important when reversing type. The chosen font may need

to be increased in size and weight when put on a non-white background in order for it to be distinct.

Avoid switching between black on white and white on black as that tires the eyes. Also avoid

reversing out on colours that may not be strong enough to create a good contrast – colours such as

yellow and any light colours.

Navigational aids

Use features that make the layout of the document easy to follow and the information easy to find.

Re-occurring features such as headings and page numbers should be consistent in style and

format and should always be in the same position. A table of contents is helpful.

Leave a space in between paragraphs. This break makes it easier to read. An indentation of five

millimetres on the first line of a paragraph to the left of the text is useful. It helps the readers to find

the beginning of the line, especially those readers who use magnifiers.

Images

Images should not be used in isolation to convey a message. It is essential that any images be

clearly described in the narrative part of the document. If images or photographs must be

incorporated in your document, be sure that they are clearly defined in the text.

Avoid fitting text around the images if it means that the beginning of the text starts at different places

causing a ragged left margin. Images or photographs may be placed on the right side of the text as

that does not disrupt the beginning of each line.

When selecting images or photographs, bear in mind that a dark coloured foreground image against

a light coloured background is easier to read. Avoid poor contrast and busy backgrounds as they

reduce visibility. Make the illustration, image or photograph as large as possible without loosing

definition (too grainy). Avoid setting text directly over images. This will detract from the type and

confuse the eye. Some readers may not expect to find text within an image so the message may be

missed. If an image does not have a defined border, place a frame around it so that it will not be

missed when readers are using magnification programmes. It is essential that any accompanying

text clearly describes the content of any visual. If illustrations are used, ensure that the strokes are

dark and clearly defined.

Abstracts and watercolours should be avoided. If photographs are used, ensure they do not contain

too many details and do not overlay one photograph upon another. Choose a high contrast and

clean uncluttered backgrounds. One simple way to test the visibility of the image is to print or

photocopy the full colour image in black and white. Are the different shades of grey clearly

distinguishable? If they are, there is sufficient contrast.

Columns

When using columns, make sure that any gutters (margin surrounding the columns) are clearly

separated. Columns that are too close together may confuse the reader. If space is limited, place a

vertical line to separate the columns. Avoid putting images within columns as they disrupt the flow

of the text and may confuse the readers. Tables and columns are difficult to produce in formats

such as Braille and audio; and they may also complicate the procedures for screen readers. It is

advisable to incorporate all pertinent information in the tables into the text and not to solely rely on

the table to convey your message.

Paper

When selecting paper, avoid glossy paper as it reflects light and glare making it more difficult to

read. Choose uncoated paper that is at least 90 gsm (copy paper is normally 80 gsm) so that the

paper is not too thin. If it is, text may show through from the reverse side.

Be aware of where the paper is folded. Avoid creases which obscure the text. Make sure that the

centre margin is wide enough to avoid text printing too closely to the spine as it will appear distorted

when photocopied or scanned. People who use scanners or screen readers need to place the

document flat to enable the software to properly display the material.

Perfect binding, such as is used in paperback publications, should be avoided as it is too difficult to

flatten the document. Documents that are too large (A3+) should be avoided as they are too

cumbersome. Documents that are too small (A5 or smaller) require the constant turning of pages.

When preparing the document, it is essential to consider all the above aspects. They all have an

impact on how well your document will be ‘viewed’ by your audience.

Clear Print in Practice

This is a guide on how to set up the ‘clear print’ recommendations in your document. To save all

your formatting and styles so that you have it as a standard or default, open MS Word and have a

new document screen, follow the steps below and when finished, save it as a Template. If this is a

formatting style unique to a particular document, follow the steps below and, when finished, just

work on your document and save it as usual.

Putting Clear Print into Practice

n

From the Menu bar, select Format, then Style.

n

Start with Normal since all subsequent styles are based on it.

n

Select Normal, then select Modify.

n

Select Format at the lower right. From here you can set Font, Paragraph, Tabs, Border,

Language, Frame and Numbering.

n

Under Font, select Type Face. This will give you the family names of the fonts such as

Arial, Helvetica and Times New Roman. Next select Font Style = Type Weight. This will

give you the option for Regular, Italics, Bold and Bold Italics. Finally, select Size. When

finished, click OK.

n

This will bring you back out to the Modify Style screen. Select Paragraph next. This will

allow you to define your leading (space in between paragraphs and headings).

n

Alignment – Make sure Normal text is set to the left.

n

Indentation – The Left and Right denotes how much the entire paragraph should be

indented from the margins. If you want to indent on the first line, you need to go to the

drop down menu under Special and choose First line, then denote the indentation under

by: e.g., 0.5 cm.

n

Spacing – This section allows you to build in carriage returns before and after each

paragraph so there will not be any unnecessary returns. Setting ‘Before’ and ‘After’ to 6

points will help to separate the text for ease of reading. Under Line Spacing - it is

advisable to select 1.5 for ease of reading.

n

Click OK when finished with Paragraph settings.

n

Click OK in the Modify Style window.

n

Click Apply in the Style window.

This guide provides the basic steps to establish your ‘clear print’ practices. Other styles and

recommendations may also be applied using this technique.

Clear Print in Production

This section will describe ways of producing your document in each of the specified formats.

It will include helpful hints highlighting accessibility issues and information on outsourcing the

production of the document.

MS Word

The electronic MS Word file you produce will be the master document. This document should

incorporate the suggested steps. This master document must be updated with any editorial

changes. It will be the copy for the print, the Braille, the audio, the HTML, the large print and the

PDF versions.

Once the master document is produced, it will be forwarded to the printer. Most printers do not

use word processing-based software to transform your document into the finished product. The

master document you send them will be converted to a desktop publishing file. It may be in

QuarkXPress™, Adobe® InDesign® or some other similar package. It is from these files, your

printer will design and layout your document for print.

It is crucial that every edit and/or update is incorporated into your master document. Any changes

from subsequent proofs from the printer must be made to your master document. {Publishing

software packages are not word-processing based, therefore, any subsequent conversion back to

Word will result in the loss of all applied ‘clear print’ styles to your document.}

Large Print

Large print documents are of benefit to partially sighted readers. Large print documents should

be produced adhering to the ‘clear print’ procedures and they should be as close as possible to

the standard print version.

When creating your document in large print, ensure that the font size is at least 16 points. 18

points font or greater is the preferred size. If your document is only one page, it may be

acceptable to enlarge the document using a photocopier. However, it is not advisable to take

such a step when the document is more than a few pages because photocopies lose contrast and

print weight when they are enlarged.

Process

Large print may be simply produced once the document is created following the accessibility ‘clear

print’ procedures mentioned previously. A minor change under the font size in the Style function

under Normal will be able to render all text in the document to large print. Once you have changed

the Normal font size, all the other Heading font sizes will follow suit. Select apply and the entire

document will be updated in the new enlarged font sizes accordingly.

As with any print document, ensure that the design and layout is simple, easy to follow and

uncluttered. Ensure that there is a proper contrast between the type, the background and the paper

for printing.

A problem with large print documents is that the pagination differs from the regular version.

However there are ways to minimise this problem:

Divide the document into clearly labelled sections and chapters;

Use shorter paragraphs;

Number the paragraphs and

Review pagination once the large print has been set. If page 1 translates into three pages, use 1/1,

1/2 and 1/3. When referencing the document, use section or chapter titles rather than page

numbers.

Non-textual Contents

If your document contains photographs, graphs, charts or tables, creating a large print format will

require some time to enlarge these visual items. Depending on the nature and size of these nontextual contents, it is advisable to describe the essence of the data in the body text to avoid

unwieldy duplication and the enlargement of such items. It is advisable when creating accessible

documents that all non-textual and visual graphics be kept to a minimum.

When enlarging photographs and other visuals in the document, be aware that certain graphics do

not enlarge properly. The image may be distorted or become too grainy. People with visual

impairment may only see a small part of the visual at one time. If that is the case, consider omitting

the visual and providing a clear description of the visuals in the body of the text as an alternative.

Also, ensure that text is not wrapped around any graphics nor split into multiple lines, does not have

uneven gaps, does not contain all capital letters nor is unnecessarily aligned, as these may cause

problems and difficulties for some users.

Alternative

An alternative to creating a large print format in-house is to request your printer to typeset and layout

the exact version of your document in large print – size 18 points or larger. However, if it were

necessary to produce an exact duplicate of your document in large print, this would be advisable.

Braille

Providing a Braille version of your document requires forward planning. The Brailling processes

described below refer to Grade 2 Braille.

Process

Braille is produced using a Braille translator programme and an embosser. The Braille translator

programme (for example, Duxbury) processes a text-based document (such as a Word.doc or a .txt

file) into the necessary symbols for the embossing of Braille. Braille translation programmes are

incompatible with graphical desktop publishing packages such as QuarkXPress™, Adobe®

PageMake® or Adobe Portable Document Format® (PDF) files.

Procedures

Principles of proper word processing are important to observe when producing Braille documents

because the translation software takes word processing styles and other specialised indicators into

account. For example, a tab stop beginning a paragraph in print is translated into to two blank

spaces that denote the beginning of a paragraph in Braille. Braille translation software renders

bulleted points, italics, bolding, underlining and other similar styles into specialised configurations

recognisable to Braille readers.

Pictures, diagrams, tables, charts and graphs are difficult to render into Braille. When using visuals

in your document, it is advisable to clearly describe in text the essence of the visuals. All relevant

information derived from the visuals should be clearly described in the text. Simple tables can be

translated into Braille. A proof reader should ensure that all the information has been correctly

converted into Braille. Braille pages are slightly larger than A4. They are generally 12” x 12”. When

publishing in Braille, be sure to order from the printers front and back covers and interior dividers, if

applicable, in the correct size for the Braille version. This will ensure that the covers of both versions

will be similar.

Timing

There are only a few places in Ireland that provide a Braille service. There is usually a two to three

week production period to convert the printed document into Braille. This actual time depends upon

the size of your document, the amount of editing and the number of copies required.

Costs

The costs of Braille production depend on the number of pages and the format in which your

document is delivered. (The prices quoted below are a guideline and are correct at the time of

printing.)

Document provided on disk or email (Word document)

A4 of page print = approximately 2 Braille pages

Master cop

Additional copies

€2.00 Braille page

€1.00 per Braille page

Document provided to be scanned

Note: Not all document features are suitable for scanning (i.e., columns, tables, certain types of print,

etc.)

A4 print page to scan

€4.00 per page

Braille copy

€1.00 per Braille page

Document to be word processed

A4 page to word process

€5.00 per page

Braille copy

€1.00 per Braille page

Binding and Covers

Covers and binding

€10.00 per copy

Resources

Braille Centres in Ireland

The National Council for the Blind of Ireland

The Media Services Production Unit

Whitworth Road

Drumcondra

Dublin 9

Tel: 01 830 7033

Fax: 01 830 7787

Email: info@ncbi.ie

Web: www.ncbi.ie

St. Joseph’s School for the Visually Impaired

National Braille Production Centre

Gracepark Road

Drumcondra

Dublin 9

Tel: 01 837 3635

Fax: 01 857 1079

Email: mcooper@braille.ie

Note: The National Braille Production Centre at St. Joseph’s School for the Visually Impaired

concentrates on the production of school books in Braille.

Arbour Hill Prison

The Brailling Unit

Arbour Hill Prison

Dublin 7

Tel: 01 673 2949

Fax: 01 679 9518

Tactile Covers from Sweden

Iris InterMedia

Kristiansbergsvägen 5

SE-737 30 Fagersta, Sweden

Tel: +46 (0) 223 424 23

Web: www.irisintermedia.se

Note: It is possible to get embossed covers with tactile illustrations and Braille text from Iris

InterMedia.

Audio: Cassette or CD-ROM

An audio format of your document will benefit the visually impaired and may be the preferred

version for those who have reading difficulties. It may also be the choice of those without

difficulties.

Once your document is produced based on the ‘clear print’ procedures, it is quite simple to

modify the document for audio recording. The finished document is sent to a printer for

layout, design and print, and simultaneously, the audio version is produced in a recording

studio. An alternative would be to produce an in-house version. However, the in-house

production would not match the quality of a professional production.

The commissioning and production of the audio version requires forward planning to allow

adequate time for completion of the process. It is advisable to consult experts in the area of

production. {A list of some available resources is provided at the end of the section.}

Recording Medium

Audio cassettes are available in C60, C90 and C120 for recording. A C60 tape can record

up to 9000 words and a C90 tape can record up to 12,000 words. C120 tapes are not

recommended for repeated usage since they are prone to breaking and tangling in the

cassette players. They are also too unwieldy for retrieving information quickly. Compact

discs (CDs) generally hold about 70 minutes of audio data. Each A4 page of text translates

into three to four minutes of recorded time.

Visual to Aural

The author has a responsibility to prepare the document in such a manner as to facilitate its

oral presentation. The author should also bear in mind the conventions that assist the

production of a voice over. Here are a few suggestions on how to accurately convert your

document from visual to aural impact.

Written headings are essential to help a listener to ‘glance’ through a publication. The verbal

equivalent is a numbered content list (e.g., 1, 2, 3 or a, b, c etc.) for ease of reference. At the

beginning of each tape, the reader will record announcements that are basically a mini

version of a table of contents.

Announcements contain information such as the title and author, the contents of the track

(side one or side two), the printed pages recorded in that cassette, the length of the

recording and a note of the indexing styles to indicate new headings, sections or chapters.

The announcements are usually left blank and then recorded at the end of the production of

the tape.

If your document requires more than two cassettes, it is also advisable to create an index

cassette, which is the directory to the audio set. This index is divided into two parts. The first

part provides a list of the cassettes and tracks used and the page numbers each contains.

The second part contains a list giving the starting point of each chapter, with the page,

cassette and track number. Overviews and executive summaries should be given for longer

documents. These may be recorded separately like the index. These added features will

give the listener greater flexibility to ‘browse’ through your document with ease.

Additional and Non-textual Contents

The reader will read all printed material, page numbers, notes, footnotes and references. For

notes, footnotes and references, it is generally advisable for the reader to read them after the

body text. If the body text must be interrupted to insert these notes, the reader will indicate

such a break upon interrupting the body text. Single word quotations and very short phrases

can be indicated by tone of voice. Otherwise, the reader will say ‘quote’ and ‘unquote’ or

‘end quote’. Italics and bold, when necessary, can also be indicated by the tone of voice. It

is not advisable to use such techniques to emphasise the information.

To accurately convert diagrams, illustrations and photographs in your document, it is

advisable to provide a concise description of them. The objective for the reader is to convey

the author’s intent to the listener.

For graphs, charts and flow charts, the reader will read the title, source and caption provided.

It is essential that the accompanying text adequately describes the diagram. For more

complex charts and graphs, it is advisable to provide a concise description of the item in

discussion rather than to read each level and box of the diagram.

Tables are generally read across after describing the number of columns and their headings.

All captions, legends and auxiliary information will also be read. However, depending on the

nature of the content, tables may be read across or down. In such an instance, it is

advisable for the author to clearly describe the essence of the table and to ensure that the

reader adequately conveys the message to the listener as the table is being read.

Labelling

All cassettes must be labelled immediately after recording. It is advisable to request labelling

on one side only – side one. Adopt a consistent system of labelling to show the title, the

author, the cassette number {if part of a multiple set} and tactile or Braille labels for both the

cassette and the plastic case.

Post Production

Once the original cassette(s) or digital track is produced, it is advisable to keep a master

copy from which all other copies and formats may be produced. As cassettes become worn,

it may be necessary to produce replacement copies. The master copy may be produced

either in cassette or CD-ROM form. The advantage of CD-ROMs is that they may be tracked

for easy navigation and portability, especially for multiple sets. It is also advisable to have

audio versions in MP3 or WMA formats for downloading via the Internet. If these formats are

required, be sure to convey this to the production studio at the onset to avoid extra

conversion costs later.

Future of Audio format

With the advance of technology, audio files may now be streamed with text and graphics to

create DAISY documents. DAISY (Digital Audio-based Information System) is a system of

both hard and software used to maximise the navigation capabilities within the document.

Files created in such a format allow partially sighted users to both ‘see’ and ‘hear’ the

document. However, this format depends upon specific hard and software requirements.

The discussion of this system is beyond the scope of this document.

Costs

The costs of audio production depend upon the size of the document, the final delivery

formats and the number of copies, in addition to professional reader and studio fees.

Be aware that the lead time to source and book professional readers or studios may be up to

three or four weeks and allow two to three weeks for the actual production. Professional

readers can generally read continuously for twenty minutes without a break. They can

normally record up to four hours at a time.

Resources

Audio production centres in Ireland

The National Council for the Blind of Ireland

The Media Services Production Unit

Whitworth Road

Drumcondra

Dublin 9

Tel: 01 830 7033

Fax: 01 830 7787

Email: info@ncbi.ie

Web: www.ncbi.ie

Prices from NCBI are as follows: (accurate at time of printing)

Studio rental:€1,680.00+ per day*

Master copy: € 4.00 per recorded minute**

Extra copies: € 2.50 per audio cassette/CD

*In this instance, you would be supplying your own reader.

**In this case, the NCBI would be providing the studio, the sound engineer and the reader.

There are many other recording studios in Ireland. Be aware, however, that the costs vary

between the different studios.

Electronic Formats

People with visual impairments may access electronic files through assistive software and

technology such as JAWS, Windows Eyes, Supernova Reader Magnifier, and Kurzweil.

These screen readers and magnifier applications assist people with visual impairments to

‘view’ documents by converting text to speech.

HTML

One of the more popular electronic formats is HTML (Hyper Text Markup Language) which is

also used to create web sites. Creating accessible HTML requires a multi-step process. For

the purpose and scope of this document, we will examine techniques to be used and steps to

be taken by the author to facilitate the conversion required in the creation of an accessible

HTML file from a MS Word document and which in turn will be uploaded onto a web site.

However, even if your document is accessible in HTML that does not mean that the web site

on which it sits is accessible. So in creating accessible HTML, you will need to ensure that

the content is accessible and also that the design and features of the web site are also

accessible. Code-specific practices to make your web site accessible are beyond the scope

of this document. However, they are issues that your web developer should consider when

creating the web site.

Accessible HTML document

Creating an accessible web site and content within the site benefits not only those with visual

impairments but also people who do not have the latest browsers or those who wish to view

the site text only. With this in mind, the contents, design and features should be sufficiently

flexible to enable them to be adjusted to suit each user’s requirements.

Here are some good practices for the author to ensure that the document is accessible when

converted into HTML. These suggestions are extracted from the Irish National IT

Accessibility Guidelines (published by the NDA) which are based on the guidelines published

by Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) which is part of the World Wide Web Consortium

(W3C).

Ensure your document contains a proper structure.

Headings

When creating your document, ensure that you apply the proper document structure. Use

the ‘clear print’ procedures to create headings. This is vital to the conversion of the

document to an accessible HTML file and to the mapping of the document. Do not simply

bold or increase the font size to indicate headings.

Lists

When creating lists, use the numbered and bulletted function in MS Word. (From the Menu

bar, select Format then Bullets & Numbering.) Manual insertions of numbers will not

properly convert to a list in HTML. When deciding whether to use numbers or bullets,

consider whether the items require sequential order or not. The look and shape of the bullets

are irrelevant.

Ensure that your document is clear and simple.

When writing, ensure that you clearly define and express the purpose and objective of the

document. Keep the sentences short and concise. Do the same with paragraphs.

Provide an alternative text to visual content.

If your document contains non-textual content such as graphs, photographs, illustrations,

diagrams or charts, ensure that you provide a meaningful alternative textual explanation of

the element and how it relates to the body text. Text is the most versatile. It may be read,

displayed and converted into Braille. People using screen reader software will be able to

access such non-textual contents. Images should not break up the text. Images may be

inserted at the beginning or end of a paragraph but not in the middle of the text. Ensure that

the images do not contain fine details. Use high-contrast illustrations so that no details are

lost.

Do not rely on colour alone.

People with visual impairment may not be able to distinguish colour emphasis within the body

of the text. Ensure that the colours used in your coloured document have a good contrast

especially when converted into HTML. One way to ensure this is to print a test page of your

coloured document (text and all non-textual contents) in black and white and determine if all

the grey areas are distinctive and identifiable. As a general rule, contrast dark colours with

light colours. Avoid pairing colours such as red and green and blue and yellow as to a

partially sighted person these combinations may cause confusion.

Use tables properly.

People with visual impairment often use screen readers to access the Internet. Most screen

readers read tables from left to right across the table. With this in mind, it is advisable to

avoid complex tables, which should be broken into smaller tables. Only use tables for tabular

data. Tables should not be used for visual layouts.

The above practices facilitate the easy conversion of an MS Word document into an HTML

file. Here are some other techniques to consider when creating accessible files.

Do not provide numbered cross-references. When the file is converted into HTML, the

numbering may be rendered useless.

Avoid using the spacebar for indentations and tabs or the return key for formatting purposes.

Keep the format of the document as simple as possible. Avoid using text boxes, Word Art,

text animations or columns.

If the document is created using MS Word, it may be easily converted into HTML by

choosing FILE and Save as Web Page or Save as Web Page, filtered if you use Office XP.

The second option removes MS Word junk from the HTML file and the file then stands a

better chance of being valid HTML. This is important for accessibility.

If you use Office 2000, you may download a filter from Microsoft that also removes the MS

Word specific junk. This is available at

http://office.microsoft.com/downloads/2000/Msohtmf2.aspx

Similarly, there is a number of free programmes, such as HTML Tidy, which also remove MS

Word junk from the converted HTML file. HTML Tidy is available at

http://tidy.sourceforge.net/.

Accessible Web site

Now that you have saved your document as HTML, you may need to insert some specific

code into the HTML to aid the accessibility of the content. For example if you use data

tables, you would need to insert mark-up (HTML code) for the headings in the tables and for

the table summaries. Writing HTML is beyond the scope of this document as is advice on

how to build accessible web sites. However you can get good advice on both these topics in

the Irish National IT Accessibility Guidelines (published by the NDA) from the Web, available

at http://www.accessit.nda.ie. As the author, you should ensure that the web developers

adhere to these guidelines in order to facilitate the accessibility of your document.

Guidelines

The Irish National IT Accessibility Guidelines, (published by the NDA), includes guidelines for

the web (based on the WAI WCAG’s), telecoms, software applications and public access

terminals. http://www.accessit.nda.ie.

The W3C Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) homepage http://w3.org/wai. The Web Content

Accessibility Guidelines v 1.0 (WCAG 1.0) http://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG10/ and the

checkpoints http://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG10/full-checklist.html.

Web Accessibility Evaluation Tools

Accessibility Toolbar is a useful plug-in for MS Internet Explorer. Here are links to many

tools that are available online http://www.nils.org.au/ais/web/resources/toolbar/.

Aprompt is another useful site for free tools. http://aprompt.snow.utoronto.ca/overview.htm

Bobby – the free online version. Be aware that compliance with Bobby does not mean

comprehensive accessibility. http://bobby.watchfire.com/bobby/html/en/index.jsp

Tutorials and ‘How to …’

“Dive Into Accessibility” is a good online tutorial on accessibility by Mark Pilgrim

http://www.diveintoaccessibility.org.

Tips on how to evaluate web site

accessibility: http://www.webaim.org/techniques/articles/freetools/. Webaim also offers

online seminars and training.

Tips on how to maintain an accessible web site using MS Word and XML:

http://www.xmlw.ie/events/04-01-03.html#.

Often the first step to ensuring that content can be easily transformed into accessible HTML

is to ensure that the content is initially captured in a well-structured format. This article

contains tips on how to create well-structured MS Word documents that are in turn relatively

easy to transform into accessible HTML. http://www.webaim.org/techniques/word/.

Writing for the Web

‘How Users Read on the Web’ (useit.com) – http://www.useit.com/alterbox/9710a.html

‘Applying Writing Guidelines to Web Pages’ –

http://www.useit.com/papers/webwriting/rewriting.html

‘Inverted Pyramids in Cyberspace’ – http://www.useit.com/alterbox/9606.html

PDF

The acronym PDF stands for portable document format. The original purpose of PDF was to

create a printable file that would be operating system and software independent (other than

the free Adobe Acrobat Reader) so that the document could be viewed on any computer.

The PDF format was not intended for screen reading. However, due to the benefits and

popularity of such a format, many web developers and users welcome this additional

alternative in providing their content.

However, although more and more screen readers are able to ‘read’ PDF files, PDF files are

not as accessible as HTML files. In order for PDF files to be more accessible, there are

some conditions that must be met.

The user must have a version of Acrobat Reader that includes an embedded speech

synthesiser.

The user must also have either JAWS or Windows Eyes to ‘read’ PDF files.

When the users have all the software requirements, then the document must contain ‘live’ or

‘real’ text. The document must also contain proper PDF tags and must be marked up for

accessibility (only possible in full versions of Acrobat 5.0 or later). PDF files must go through

an ‘accessibility proofing’ process by developers to ensure that they can be accessed by the

screen readers.

Creating PDF from Word

When creating PDF files from MS Word, it is critical to adhere to proper authoring techniques

to ensure accessibility. In order to easily create accessible PDF files, it is essential to

understand the workings and limitations of screen reading software packages and how they

translate PDF text to verbal content.

For a PDF file to be accessible, it must have ‘live’ text not ‘scanned’ text. Screen readers

can only read ‘live text’ that is properly tagged. Accessibility also means that the document is

read in a proper order, not necessarily the way the document is designed. Full PDF

accessibility will enable the structure of the content to be accessible, not just the words.

As the author, it is important to adopt the ‘clear print’ procedures whereby the structure

(headings and lists) of the document is consistent and used properly (e.g., no unnecessary

returns, tabs or spaces). When used properly, later versions of MS Word (MS Word 2000 or

later) would be able to properly convert the word document into an accessible PDF file. Here

are some steps necessary to be taken in order to create an accessible file.

Alternative Text for Images

Alternative text for images is required for accessibility. You should ensure all images in the

document have a concise and relevant description. Screen readers read all alternative texts

in PDF.

Design and Layout

Graphical lines are for decorative purposes only. If your document requires features such as

a text box or graphic lines to break up the text, consider using the Borders and Shading

functions in MS Word to create the visual effect. Avoid using the Drawing tools.

The same ‘clear print’ principles apply when selecting text and background colours. Ensure

there is optimum colour contrast. Avoid using colours, bold or italics to emphasise points.

State such importance in the body of the text. Unlike readers for the audio format, screen

readers do not apply a different tone when such styles are implied to words.

Document Structure

The proper formatting of the document structure is essential to map the document. Ensure

the proper headings are used. Similar to Word, each heading and sub-heading is created to

reference the exact point in the document. Avoid using unnecessary headings as the screen

reader will repeat them. Instead use Headers and Footers to display information you would

like to be displayed consistently throughout the document.

When creating lists, use the Number and Bullet functions in Word. Manual insertions of

numbers will not create the necessary PDF tags to alert screen reader applications that it is a

list.

Paragraph return notations must be used properly. Empty returns must not be used to

create breaks between paragraphs. Doing so would interfere with the PDF document

mapping process by creating ‘blanks’ in the map. Similarly as with paragraph returns, do not

use unnecessary tabs or spaces to indent.

Proper use of Tables

Similarly to HTML, avoid using tables for layout purposes unless the content makes sense

when read across. Instead, use the Column function in MS Word to create the same effect.

Text boxes are not recommended either as screen readers are not alerted to read the text in

visual order but rather in creation order.

These are some of the significant author related issues in creating PDF files.

With the advances of Adobe, it is now possible to access PDF files using screen readers.

However, only certain types of screen readers are able to convert text into speech and that

also depends on the version of Adobe Reader used. Because of such limitations and user

requirements, the most reliable way to make a PDF file accessible is to convert it into

accessible HTML.

For more information on accessible PDF files, visit the following web sites:

www.webaim.org

www.adobe.com

http://access.adobe.com

CD-ROM

When creating a CD for your document, ensure that your CD writing software is set up

properly to facilitate all CD readers. When saving the document on a CD, ensure that the CD

is recorded at the lowest (4x) speed so that computers and laptops with older CD readers will

be able to access and read the file. The writing of the CD at such speed will take longer but

it will ensure greater accessibility. If your printer produces your CD, please request that the

CD is written at the lowest speed possible to guarantee maximum accessibility.

Standard Print Publication

Once your master Word document is ready to be published, it will be sent to your printer.

From there, it will be formatted using desktop publishing software to add in layout and

design. Be sure to meet your printer to discuss the layout, design, colours and paper to

ensure the finished publication adheres to the ‘clear print’ requirements. If other formats

need to be produced the printer should be advised of the extra requirements such as labels

and covers.

Allow time for the different stages of production. The length and specifications of your

document will have a bearing on the time required.

Printers would normally charge a

professional fee covering design and layout costs. The printing fee is separate and is

dependent on the paper type, its quality, the binding and the quantity.

Extras Covers or Inserts

When you have decided on the various formats for your document, consult your printer and

order extra front and back covers, internal dividers, CD covers, and/or audio cassette covers,

if applicable, to ensure a professional finish to your document in all of its formats. Convey

this at the onset to avoid incurring unnecessary additional charges by virtue of a late order.

Additional services

In addition to the published standard copy of your document, your printer may also be able to

provide you with other formats such as PDF and HTML. Be sure to request accessible PDF

files. Some publishers offer proof reading and editing services.

Bibliography

“A Guide to Making Documents Accessible to People Who Are Blind or Visually Impaired”,

Jennifer Sutton, American Council for the Blind (Washington DC: American Council of the

Blind, 2002).

Accessible Documents, (United Kingdom: Trade Union Congress, Equal Rights Department,

1996).

Adobe Acrobat Accessibility Techniques, (WebAIM, www.webaim.org, 1998-2004).

Guide to Authors of Accessible PDFs, Julian Rickards, (Canada: Government of Ontario).

How To Provide Information Well - A Good Practice Guide, (2nd Edition, United Kingdom:

National Information Forum, 2002).

Introduction to Alternative Media, (Cupertino, CA: High Tech Centre Training Unit, 2003).

Listening and Learning: Booklet 2, (United Kingdom: Royal National Institute of the Blind,

2003)

Producing Accessible Information A Practical and Strategic Guide, (United Kingdom:

Employers’ Forum on Disability, 2000).

See It Right Pack, (United Kingdom: Royal National Institute for the Blind, 2002).

Ways to Make Written Documents Accessible to All, (Ireland: The National Council for the

Blind of Ireland).

“Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 1.0”, Wendy Chisholm and Gregg Vanderheiden,

W3C (World Wide Web Consortium, 1999).