1 Tickled Pink / Webster “Tickled Pink” is a story from a set of related

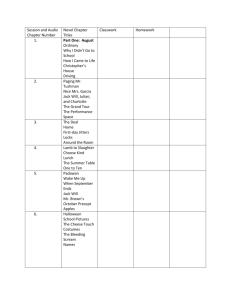

advertisement

“Tickled Pink” is a story from a set of related stories under the title What to Do in Case of Fate. Characters named Henry Horse, Percy Baldridge, Olivia Piano, Greta Mann, Alice Doren, and Jack Popcorn – are featured at least once in youth and at least once again at the midpoint of their lives – either as the central character in a particular story or as a minor character in another character’s story. “Tickled Pink” is split it into two parts for submission to BCWW sessions. Part One is below, and the cutoff point is arbitrary. Tickled Pink by Gary Webster The seamen call it looming… Its principal effect is to make distant objects appear larger, in opposition to the general law of vision, by which they are diminished. I knew an instance, at York town, from whence the water prospect eastwardly is without termination, wherein a canoe with three men, at a great distance, was taken for a ship with its three masts. - Thomas Jefferson With discipline and by masquerade, Zach Gotlieb, city editor of the Stone Mountain Post, permitted himself no outward signs of pleasure in his work. In this, he was like his face. Folds of fat concealed good looks. Two decades of stern labor had lent to the fat a texture like gristle, the result Tickled Pink / Webster 2 of rigid bearing, strenuous judgment, maniacal speed, and a pledge to accuracy. This, he applied over many years to a chain of grindstones that he turned one by one into dust, all while conducting himself in the manner of a taxi cab dispatcher, as opposed to the manager of a literary enterprise. Yet, the drab toil was spiced with a secret, freakish twinkling in his psyche. There, he cloaked a circling Hollywood spotlight, switched on during his youth, but not turned to the sky. The light lodged in the dark recesses of his body where it never flared out. To his crew of nine reporters and assorted freelancers, he was thorny and biting. That’s the style that made it happen. But at home, knocking back his toddy after sundown, he was Cary Grant, he was Spencer Tracey. Solo, by the red-hot glowing fireplace, he was Jason Robards, he was Lee J. Cobb. He never let the peculiar gleam show. He did not permit even Mrs. Gotlieb to glimpse it. The lambent inner light was his most intimate belonging. Thus, a disillusioned man preserved the trace of an illusion, tucked away in his heart. It was inextinguishable. It was incorruptible. At his desk, he affected weariness and boredom. He was a virtuoso of gray monotony, until abruptly he ignited. He was a man who could light a blaze. The trick was in the surprise, in the rarity of the explosions. Anger, tremendous anger, and best when he was actually angry. If the force of something terrible welled up inside, then it took over his otherwise tranquil methods and procedures. Into the sunless newsroom he brought lightening. The city editor’s discharge rejuvenated the place and to a high degree satisfied him. He whipped off his jacket upon arrival at the office. He got down to work, he got the newspaper out. But also, he seized his hirelings like the overlord of a totalitarian reeducation farm. He considered transforming young idiots into reporters the main object of his work in providing the isolated county of Stone Mountain with news. That was his deepest secret. He wanted young idiots Tickled Pink / Webster 3 to say, years later, I owe it all to Zach Gotlieb at the Idaho rag where I started out. Thin gruel, but that’s the way it was with Zach. A simple, heartwarming message from the big time world, borne back to Stone Mountain, perhaps in a note hastily scribbled on pulpy scratch paper. To Dear Old Bullet Eyes – you taught me how to be a reporter. That was what he wanted. The way Rosalind Russell said it to Carey Grant, Rosalind reading the line hardboiled, no purring. Anyone Zach wanted to say it that way would be long gone from the Stone Mountain Post by the time it could be said. He knew very well who it should be – he knew exactly who ought to say, I owe my success to you, Zach. He was getting on, and he realized that he might be long dead when word finally came that he was appreciated. Eighteen years and nothing. Not a single note to that effect. No phone call. No nothing. Well, fuck it. If you really needed what you needed, then you were a sap. And then you had to get the story, too. That was the thing – the story. Everyone said that. But the story was only part of it. No one said that. The story gave the business a hard edge, concealing that dreamy shit. The sentimental crap. Bury the crap. Even though the crap was there, and Zach knew it was there. Fuck it. Zach Gotlieb liked to scold the dreamers. The deluded egomaniacs who wanted to be reporters, rub elbows with the powerful, and make a name for themselves. He liked startling them. He liked using his pencil like a sword to scratch diagonal black lines across two-and-a-half pages out of three pages of copy and demanding a rewrite in the next twenty minutes. He liked badly written copy. It made his day. In a way, he didn’t like good writers. He didn’t much like the kid who could do the job well. Beginner’s luck. They were here and gone, they hardly noticed him. He liked the dreamers who didn’t know what they were in for. He liked to drum them out, or push them on and up. Either way. He liked the slow ones. He liked molding them. He liked making them into reporters. He liked chipping away at their noses until they were misshapen and blistered. Sometimes his gruff magic actually produced a tough-son-of-a-bitch reporter who cared nothing for the dreamy Tickled Pink / Webster 4 shit. He believed it had happened. Several times. Good enough odds, you’d think, to produce one lousy note. The bastards. “Hey, Popcorn!” “Yeah, Zach?” “You hear of something called darklight?” “Nope. You mean like strobe light?” “No. The religion.” “Uh… no.” “Take a day, see if you can find something.” “Uh… the library?” “That’s a start. Got something to do with Indians. You’re an Indian, aren’t you?” “My great grandmother, supposedly.” “What kind was she?” “Uh… Ohio? Don’t really know. Nothing fancy like an Apache. Dull as corn.” “Too bad. Well, darklight… Indian religion. Or something. Check it for me, will you? Maybe a story.” “American Indian, you mean? Not the other one?” “American. Try the U. of Q. Ask around. Ask the weird people… it’s a cult like. Talk to some Indians.” Zach Gotlieb pulled the darklight card every couple of years. Not one of his victims fished out a story. And yet, someday something to write about might turn up, because he was given to understand that some half-whimsical darklight religion, covered by Indian feathers, was surely out there, circulating in the interminable distance or some higher places, with the general population, like Zach, lightly tickled by word of it, but heedless and unknowing. It was news – potentially – even Tickled Pink / Webster 5 though it was like saying, “Go dig up a story on the number three.” Certain scrubs could always come back with something. Many people believe the number three is lucky – but is it? And what is luck, anyway? And so on. Jack Popcorn, boy reporter, starry-eyed, still waiting to be well kissed, was perfect for the darklight beat. A model victim with a whole day to spare. Zach desired to pummel one of those pretty doe eyes to make the boy walk around with it swollen and blackened for a week. If he could also twist Jack’s leg to cause a lifetime limp… but then, no… that would be going too far. Yet he seethed to stamp his brand on the young idiots, to puncture them with a small, dark, and ineradicable borehole for them to wear through life and ponder. There was a chance Popcorn would learn something from the darklight beat that would light a fire in his ass, and perhaps, in later years, he’d thank old man Zach in his retirement. For, according to the city editor of the Stone Mountain Post, young idiots were headed for damp, pathetic lives if they couldn’t take a punch. *** The Mystery of Secret Sacred Places by Jack Popcorn There is one roadblock to writing the truth. The author must deviate from logic without losing contact with logic. Poets daily try to pass magically through the roadblock; philosophers daily try to go around it because, if they attempt to go through the roadblock, it becomes a trap. Mr. Thomas Jefferson of Albemarle County, Virginia, philosopher extraordinaire, enjoyed navigating a logic system of hidden roadblocks, and seems to have been quite comfortable even when at times he stepped into the camouflaged hole and slid down the chute. Since the fall is simply a breakdown in reasoning, no harm is apparent and the climb back out of the hole is easy, like teleportation. All the Tickled Pink / Webster 6 philosopher need do is flip a few words around – nothing too hard, nothing dangerous. A philosopher is not obviously like an engineer when making a mathematical error that causes the death of a traveler when the bridge collapses. A philosophical error collapses like a puff of smoke, quickly vanishing. No evidence. Therefore, it’s unwise to blame the philosopher who hurts. A philosopher himself often doesn’t notice the mistake. For example, Jefferson measured out just the right amount of inferiority in the African soul, if not to justify, then, at least, to explain the fact slavery. This is like first lowering oneself into the hole and then leaping out of the hole in twenty-five easy words. At the same time, Jefferson diligently searched for a reason to justify the forced separation and encampment of the Indian tribes. If reason could be found, then he never identified it. Moreover, he admitted that it could not be explained by the inferiority of the Indians, the effortless declaration that brought down the Africans. Jefferson loved truth, pursued science, identified virtues, and took pleasure in hard work. His fierce rectitude and trust in his own integrity would not allow him to turn the Indians into savages the way his less philosophical economic imperatives turned Africans into children at his disposal for employment and profit. After much study and consideration of the available evidence, Jefferson reluctantly concluded that Indians were different than but not inferior to Europeans. In that difference, he found justification for his actions. Nevertheless, it disconcerted him that neither he nor anyone else he was willing to recognize as an authority could plainly demonstrate Indian inferiority. As a result, Jefferson has been accused of a mischievous and false naiveté in lamenting the extinguishment of the Indians because it meant the destruction of the traditions, rituals, way of life and lore, which he declared to have great and equal value. Somehow, in Jefferson’s logic or in his deviation from logic, the actual individuals extinguished in the process were unimportant. For example, to Jefferson it is of no significance that Pyannto or Flaming Bush, warrior tribesman of the Wasappi, died on March 29, 1803, at 3:02 in the afternoon. Neither is it of significance that Alayamagotto or Black Theory, Wasappi medicine Tickled Pink / Webster 7 man, was created equal on September 2, 1797, at 12:30 in the morning at the instigation of parental lovemaking beneath the moon. This weak hypothesis entrapped no one, least of all Jefferson. Yet, there it was – and Jefferson was stuck with it because, no matter for what feeble reason, the government was about to separate and encamp the Indians. Discussion hour was over. Jefferson was forced to imply, and sometimes insist, that a single Indian, in all probability, is worth little, yet all Indians taken together are quite something. Among the Indian extravaganzas he had observed, he marveled most at the Indian homing instinct. He observed small groups of strangers, migrating from who knows where, arriving at precise locations in his county without a map and without ever having been there before. To Jefferson’s lasting wonder, they walked the wild country without consulting the white man for directions to these locations, the burial mounds, where they lingered sadly, and departed after a short while. Out of curiosity, and for the sake of natural philosophy, Jefferson excavated some burial mounds he found on and near his property in Virginia. He discovered no pottery shards or figurines that would open the door to insights on Indian life, of which he was supremely capable, provided he was given even a smidgen of evidence. The mounds revealed only the remains of the dead. “I found nothing,” proclaimed the greatest practical philosopher of liberty, equality, and human rights – nothing of value. *** Krt-a-brp-krt-krt-brp. At his desk through the night, Jack pounded out the story on a compact Royal portable. He hardly looked at his notes. They seemed be settled not in his brain but along his nerves, flowing toward his fingers as needed. One long paragraph. Then he typed it over again, changing words, sticking in new sentences as they occurred to him, the Royal rattling under the brisk peewee blows of the keys. He came up with new stuff fast, and broke the text into three paragraphs. Then he typed it all over again, changing words. This time slowly. Krt… brp… krp… brt-a-prp. This time four paragraphs. And then the Royal came to rest. When he looked up from the desk, he was Tickled Pink / Webster surprised to see light in the windows. He read through the story three times, scratching words, inserting words, drawing arrows to show where to move certain phrases. Then, he typed it over again. This time seven paragraphs. He realized that it was only the slightest beginning of the story. He had fancied while bending over mad dancing fingers that he was feeding energy into the bounty of his findings, with the urgency of a man setting out to fill a void in human knowledge. Now, he wasn’t so sure. No way Jack was going to hustle copy like that across Zach Gotlieb’s desk and into the Stone Mountain Post. Old Crusty Lips would easily spot in the subject a fertile new source for his rage. Not to mention, Jack had buried the lead. No one, excluding myopic creampuff lunatics, had much interest in secret societies, or in secret paths to secret locations. Few topics were as likely to set off city editors to kicking the furniture. He’d come across the Jeffersonia while researching secret societies, and in particular, the activities of the illuminati through the writings of Wishaupt, Priestly, and Godwin and their opponents Robinson, Barruel, and Morse - quite unsurprisingly leading him to Jefferson’s commentary on the freemasons, and accidentally leading to Jefferson’s treatise on the Indians. It seemed off the point, but Jack convinced himself that such information formed a background step for telling the story of darklight. Whatever darklight happened to be, Jack inclined to think that it connected with the world’s secret sacred places. He’d eaten up the day Zach had given him and a second day, Sunday, to boot, writing until past dawn. He had all day Monday before he had to show up at the office on Tuesday to face Gotlieb, very probably with nothing to show for the long weekend absorption into his brain of a batch of obscure references, now typed into seven overdone paragraphs. He fed the Jefferson sentences with esoteric hints, like a mother bird trying to make them grow. Dissatisfied, he still planned to use the data in tracking down a possible lead. Indians, darklight, secret sacred places. 8 Tickled Pink / Webster 9 Streaming vague feelings, whispers, and tickles. Jefferson’s struggles with the Indians had flipped the switch, only to illuminate fog. The librarian offered no help when he had asked her about darklight, and he found nothing in the catalogue, so he didn’t go back to the library on Monday, sleeping away most of the day to awaken in the evening thinking about the woman who had been standing next to him at the library front desk. Peroxide blond, long out of fashion. Black roots. Jack and the woman each angled over the counter, half facing each other, with the librarian in between. The woman waited her turn, nothing more. But now, in his memory, she was standing there with bright peroxide hair and eyes that jumped at the sound of the word he spoke to the librarian – darklight – as though some electric spark caused her eyeballs to hop. An involuntary start perhaps charged by nerve ends setting off simultaneous jabs in each sack of vitreous fluid. He lingered and examined. But no more jumps. They were hard eyes, deep blue surfaces spoiled by the off white cast of her sclera, like two glossy pearls transplanted by a surgeon. She aimed them at a book on the far end of the counter. On Tuesday, he fibbed to Zach Gotlieb, saying that he’d found nothing to write about darklight. But he said he had a lead. “You want to track down a woman with flashing eyes? That’s your lead?” “Well… yeah.” Zach frowned. It was one of those frowns that seemed to haul his eyes down into the lumpy tissue of his cheeks. But he said, “All right, if it floats your boat. You still have to go to the council meeting, and make sure you get in front of Jocko to ask him what the hell he’s talking about when he’s talking about municipal overburden. If that’s his platform, tell him, nobody knows what it is. Don’t let him bully you. Inside, he’s bubbles.” Tickled Pink / Webster 10 Three weeks later, Jack found the woman coming into the library past the couch near the main door where he’d been planting himself for hours and hours, mostly in the evenings, in his spare time. Determined not to give up despite the stabbing in his eyes and the headaches, induced by sunken couch-sitting and the faint odor of stale sweat rising from the cushions. He got his reward. The woman was in her late twenties, nicely structured, too. She walked with athletic lateral looseness between hip and chest. A dancer, maybe a gymnast. A high, wide set of shoulders squared off over braless, pear-shaped breasts bouncing under a black crew neck sweater. He followed her into the library stacks to the religion section. Zach had said darklight was a religion. Jack took the woman’s research choice to be a warm pointer, a payoff for all the boredom. The woman dumped her jacket and purse on an empty desk and wandered down a narrow row of bookshelves, coming back with two volumes, one of them an oversized monster of a book. Jack grabbed a random book and sat at a nearby desk where he could look through the spaces between stacks to see part of the back of her head. She didn’t get up for the next three hours, turning pages, taking notes. When she finished, she left quickly. He took a second to glance at the books she left open on the desk. The Flaming Heart upon the Book and Picture of the Seraphical Saint Teresa and The Ceremonies and Rituals of the World Religions. The first thin and worn, the second fat and crammed with etchings and lithographs of robed men circling pyres. Both books were printed in English with fonts using f’s for s’s, but he only had time for a glance. The woman was on the move. He chased after her, following her to an apartment building off campus. The next day, he called in sick, and went to the street of the woman’s apartment building before dawn. Shortly after eight o’clock, the brassy peroxide hair emerged like laser light and he trailed it. Tickled Pink / Webster 11 Those eyeballs gave her the look of someone preoccupied, as well as unfriendly. Her skin was smooth. Her face expressionless. As she moved up and down the campus with supple flow, the woman was never in danger of falling, slipping or sliding. [See description of campus from another story added to the last page of this submission.] He saw her take to the ropes, swinging from bridge to bridge. He followed her with difficulty up the gangway shortcut to the Kessler Science Building. She avoided the mechanical inclines. She liked the hard way and was conditioned for it. A student of the vertical University of Q, matriculated in full. After a while, he noticed that when she stopped, the luster evaporated. All that athletic grace seemed distilled out of her. She became rigid, transformed into a straight-backed, stiff posture, with a small head held high on a neck that was a bit too long poking out of another drab crew-neck sweater, this one navy blue. In motion, her hands and arms affected elegance. Sitting, she seemed to be made of pottery. The backs of her hands gleamed like porcelain, smeared with the faint blue cast of her capillaries. Round forehead, round cheeks, round chin, smoothly rounded off. Round elbows, round knees. Nostrils a bit too large, a bit too circular. Circular ear lobes, a bit too small. Those eyes, he noticed, bulged somewhat. Under the sun, her features had a slight exaggeration, certain protrusions had the swollen character of baubles. The hair color didn’t improve things. Yet, churning that mid-section on an under lit dance floor she would have seemed pretty. Out in the light she was an odd package. Eye-catching maverick wrangler, riding down the edge of charm’s touchy borderline. The next day, Jack followed her again, looking for a chance to corner her and approach. The opportunity came at lunch. He sat down across from her at a table in the student union as she chewed on a cheeseburger patty with lettuce in a chalky bun. To this point, the woman had ignored him, but now looked straight at him. “Get lost, buddy,” she said. Tickled Pink / Webster 12 “No… I…” “I’m calling a cop if you don’t disappear.” “No… listen… I just want to talk to you.” “I want the opposite. You have five seconds, up and gone. I promise, I’ll make a very big stink.” “No… I saw you the other day in the library…” “You’re stalking me.” Jack’s next word caught in his throat. Of course. Exactly what he was doing, from her point of view. He hadn’t thought of his tracking her that way, but that’s what it was, all right. He ploughed ahead. “Remember? I was asking… at the desk… the librarian’s desk… remember? About darklight, and you–” “Wrong line. Say goodbye.” “No… I’m a reporter… I just want–” “Reporter? You don’t look like a reporter.” “No? What’s a reporter look like?” “Not you.” “What about my persistence?” “You’re rude. That doesn’t make you a reporter. Although I’m getting it right now that you’re not dangerous. Like a pup. Pups are my forte, buddy. I wouldn’t need a cop to handle you.” “All right, then,” said Jack, deflecting her insult. “Let’s talk.” “See,” she said, “I’m missing the shrewdness about the eyes. You don’t look too shrewd. And, you don’t put in your voice any kind of arrogant twist. That’s a requirement for any reporter, I’d say. Especially when dealing with reluctant witnesses. You got nothing like aggression going on. No authority. You’re just a creepy boy.” Tickled Pink / Webster 13 “Well, I’m an apprentice.” “Well, you should’ve said so.” She seemed to be warming up to the amateur in him. “You know what I want,” he said. She put the hamburger down on the paper plate. “All right. I do. So, what if I tell you? Then, you disappear.” “Okay.” “Okay.” “Absolutely.” “You want to know what it is? What darklight is?” “Right.” “I can tell you.” She was straight up and down. Absolutely erect, shoulders straight, round chin lifted. She applied a napkin to her mouth and then said, “It’s a blast from the sky.” The woman pointed to the ceiling and then made a fist and, turning it over, put it so near his face that Jack went cross-eyed. He didn’t flinch. He tried to stay steady. The woman’s fingernails were short and dark red, painted to form a neat white nib at the pointy ends. Suddenly, she opened her hand. He flinched then. She laughed. She made another fist. She opened her hand again. He held steady and smiled. “Not funny,” she said. “Not fun. Sudden. Like this.” She remade a fist, opened it again in front of his face and held it there. “What’s it like?” he asked, peering around her open hand. “It hurts, it soothes.” She dropped her hand to the table. “At first it is the sharp tips of a thousand little stainless steel wedges. Microscopic wedges. They come out of the air. You can’t really Tickled Pink / Webster 14 see them - or, you think you can but it doesn’t really matter. What’s important is what they do once they get inside your body. These hard little bits enter like air through the nose and then . . . liquefy. Splashing over the sense organs like hot water. It saturates - the nose, the eyes, the skin - it gushes all over, you feel entirely porous. Can you imagine that? The ears, it goes, the tongue. Taking all available avenues toward the brain. Some goes straight to the top of the head, like you feel your brain floating in it. Some goes down deep into the groin and legs before, I guess like what you would call congealing at the coccyx - right here.” She tilted leftward slightly to touch the small of her ramrod back. “It all seems to gather,” she said, “and then, I don’t know, brims upward again, up the spine. You think your body fluids have gone wild, flowing outside of the normal passages. Blood splashing everywhere inside. But it’s not you, your fluids, it’s something else. It definitely enters you. From outside. It is hot enough to feel cold in spots. Oh, and quick. A few seconds. Heat and coldness pass through the limbs in waves. You see colors. Strange colors and shapes all around you. Like the world has changed. It’s an unholy fucking mix of sensational sky matter.” She smiled. “But it doesn’t last. These sensations up and down, head to toe, flooding the brain. Then, it dies away. It evaporates . . . or something. Or it’s absorbed. That’s it. Maybe. Then, it’s just a memory. Just like that. But there’s an after-taste. A taste you can taste. It’s there, it fills your mouth and nose, and it’s like for a moment you could smell with your eyes. I don’t know. It’s hard to nail down with words. Anyway, at the same time with this after-taste, there’s this odd recollection of a bright flashing boom, rolling up the nose, across the cheek, into the Eustachian tube from the inside out. A sound going backwards through the eardrum, bizarre inverted squeal. In all, sharp, violent, chubby - well, I don’t know what I mean, chubby. It’s a presence. It’s fat. The whole business makes you happy like smack, not that I do smack. I don’t. It’s sudden. It’s a bit frightening. Since you don’t ask for it. It just happens.” She shrugged. “Okay?” Tickled Pink / Webster 15 “That’s darklight?” “If you want to call it that. I call it !.” And she popped her fingers again into his face. “Yep,” she said, “that’s what I call it. It doesn’t really have a name. Just this.” She closed her fist and popped her fingers. “So now you know, and I hope you’re happy, and my burger’s getting cold.” That was it. She finished her hamburger, ignoring him. So Jack thanked her. She made no reply. He slinked off. He went away because he thought it might be significant if someone were to notice that he could keep a promise. “She’s pulling your leg,” said Zach Gotlieb from behind his desk. “No… I don’t know. You think?” “She’s got electric eyes. She’s got imagination. Tell her to write a poem. Better yet, you write one.” “My hunch says keep going.” “Your hunch? Is that where you’ve been for two days?” “I have a feeling there’s something more to it.” “And I have a feeling you can’t take rejection.” “Why’d you get me started on this, then?” “Listen, Popcorn,” said Zach. “Back in the sixties when the writings of Franz Fanon and the stink of revolution were in the air, I interviewed this guy from Nigeria who was peddling a book. He told me that if Nigeria ever got nuclear weapons, then every Nigerian missile would be aimed at London. If true, that’s a four hundred year commitment to revenge. I thought that could be a meaty story. But this was a Nigerian nobody with an apoplectic book, and so the boss shoved it back in my face. Happens to the best of them. See, Popcorn, I’m shoving this one back in your face.” “You gave me the assignment, Zach.” Tickled Pink / Webster 16 “It’s no assignment,” said Zach. “It’s a lesson for you, a lark for me, and a prank. Don’t be thick, Popcorn. Since you decided to come back to work, get your ass down to the police station. Cops battered some black guy last night and he’s screaming bloody murder.” “Give it to Carl. He’s not doing anything.” “He’d better be doing something.” “I have to follow up. Zach, it’s going to take time.” “What are you? Some well-meaning farm animal?” “I’m onto something. I want to hang out with the Indians for a while.” “Go ahead. Hang out with the Indians. Just don’t call it your job.” “All right. I quit.” “No, Popcorn. No, no. There’re misfits piled up in the lobby waiting to take your place. We use ’em up like Kleenex.” “Zach… I have to do this.” Zach made a face that might have been a reaction to a pain deep in his stomach. He put a shock of copy in front of him and began to mark it up. “All righty then, Popcorn,” he said. “Here’s to luck.” Zach’s tone was so lifeless, Jack thought he heard a crack in the base of his spine. *** Jack Popcorn had $2,663 in the bank. Not enough to live on for very long. He gave notice on his apartment, and then went to his mother to see if he could have his old room back for a while. She agreed, but her sad face creased deeply along the droopy lines, and he could tell she was suppressing a desire to sharpen her eyes, grow younger with inspired parental drive, and give him a lecture. Fortunately, she was old and tired. Still, she might eventually dig up the energy, because she barely lasted two weeks when he changed his name from Popovitch to Popcorn, a nickname his boyhood Tickled Pink / Webster 17 friends called him. “Hey, Popcorn!” He believed the name would someday make his old pals famous. “I’m going to be a writer, mom. It’s a name they’ll remember.” “Are you sure, Jack? Are you sure you want to do that?” Trying to be reasonable, but it didn’t last. His mother’s dilapidated sense of humor curbed the reach of her understanding. She actually cried about it one night, and the jobless situation was sure to bring on a delayed negative reaction. And he’d be right there at home with the task of passing by his mother in the living room every night, facing her fruitless but unrelenting objections. Well, he’d stepped into it, and he’d just have to keep walking. He decided his first step as a freelance writer was to learn more about the world’s sacred places. Jack ingratiated himself with a clique of Nottoways studying at the University of Q. They were easy to get to know. They accepted him at their table in the Student Union. There with them sat the paleface. It was a Balkan sort of Student Union at the University of Q. Negroes sat with negroes, light skin with light skin, dark with dark; Indians sat with Indians, particular tribes with particular tribes, Russians with Russians, Georgians with Georgians, Nepalies with Nepalies, Montinegrans with Montinegrans. The Italians had the so-called “mafia table,” the Inuit down from Canada had the so-called “Igloo” - and on and on, an infinity of worlds, the whole world, really, the universe of peoples, crammed into 9,600 square feet of open space, encircled around their own little tables, carefully observing imaginary border lines. Jack, in fact, was lifted out of anonymity as he became known to the patrons of the Student Union as the white man who sat with the Indians. A crew cut alkaloid among the long black hair and dark eyes. He laughed with them. He sang their songs. They talked endlessly of politics, wearily and warily. The Nottoways, a splendid and peaceful people, were not only tolerant of Jack, but were also glad to teach him their Indian names. In a few weeks time they had revealed to him the changing location of that drifting borderline they were Tickled Pink / Webster 18 compelled to cross. It was a matter of identity. Western education, Indian ways. Something of it, anyway, a taste. Ancestral mandate. Tradition. Originally an eastern tribe, the Nottoway over time had been manhandled all the way to Idaho. Jack never mentioned his supposedly Indian great grandmother to the Nottoway. He knew little about Sara Hawk except that she came from Ohio, married Sylvester Popovitch and gave birth to Jack’s grandfather, Benjamin Harrison Popovitch. Jack remembered seeing the names of Sara and Sylvester in an old family bible. Jack’s father shared no memories of Sara Hawk, except for an image from his father’s boyhood of Sara as a wrinkled old lady sitting all day on the front porch of her house in a calico dress smoking a corncob pipe. His father told him that Sylvester Popovitch was known as the black sheep of the family, probably because he came back from a short trip to Ohio bringing an Indian girl to marry. That was the full inventory of knowledge Jack had about his Indian roots. It didn’t seem like anywhere near enough to be talking about. They seemed to accept him. It was almost too easy. Now darklight, that was different. One day, out of the blue, Jack innocently asked, “What do you guys know about darklight?” Two of the three Indians at the table shot him a quick glance and one of them stared into his coffee cup and said something in the Nottoway language that spurred laughter from the other two. And then they slipped into English and a new subject, leaving Jack with a lump in his throat and a feeling of intimidation. He didn’t bring up darklight again for weeks, until the time he went with the Nottoway on a trip east during the spring break. Every year, the whole Nottoway clique traveled east to the tribe’s traditional places. If it was a secret migration, it was a secret few cared to know, so there was no harm in its revelation. Jack became closest to the Nottoway named Jim Monroe, a student of pre-medicine, who arranged with his fellow travelers – an English major, a history major, and a math major - for the white man to Tickled Pink / Webster 19 accompany them to a burial mound in the lowlands of the Rivanna River, two miles north of its principle fork, amid undulating hills where, in the old times, could be found a Nottoway town. On the first day of spring break, the delegation boarded a train and headed east to Chicago. From there, they rented cars and drove to the sacred place. The English major took one car, and the rest, including Jack, piled into the other. Jack asked why the English major rode alone. “He’s the leader,” said Jim Monroe. They drove on, sticking close to the rivers, the Kankakee, the Yellow, and St. Mary’s out of Ft. Wayne. The Scioto to the Ohio for a thirty-mile stretch, turning at the Big Sandy, going south. Along the Tug Fork to the Guyandotte, across a land bridge to the Matoaka and on to Bluestone Lake. The old roads along the rivers were the nation’s earliest highways. “Why are we winding around?” Jack, half-enjoying, half-hating the circuitous irrationality of taking the longest, most difficult possible motor route to the destination, kept thinking they “were almost there.” His question was a variation the proverbial five-year-olds dilemma – “Are we there yet?” He hoped he was asking in an adult manner what he was embarrassed to recognize as a child’s question. “We are going . . .” said the driver. “We are feeling our way along the old trails. These are Indian trails.” “We are going . . .” said the other. “About the first thing your white ancestors did was to cover these old trails with big rocks. Big mother-fucking rocks. They twisted Indian ankles, yes. But also the white man’s wagon wheels. Stupid. Progress. Stupid. But, they said, ‘That there is a real road, chief.’” “Then they tried smaller stones,” said the driver. “And bigger wagons.” “And long trains,” said the driver. Tickled Pink / Webster 20 “Little rocks. That worked better,” said the other. “Not so stupid.” “We are going,” said Jim, “to the high hole in the rock where all the rivers begin. How else can we find it unless we follow the children toward the mother? They go home to the mother.” End of Part One. Description of the University of Q The University buildings and connecting walks and ducts spread up and down the rugged mountain like a not-too-willowy vine of concrete, iron, brick, and steel. Seen at a distance, railings painted red tend to stand out in a continuous looping design, resembling, as a retiring English professor once said at his farewell dinner, “the exposed circulatory system of an asymmetrical zebra.” That fall, the University President heralded his new building program, by declaring, “This project will finally put us on the summit of Mt. Q and take us to the summit of higher education.” It was called the Hearts Outward, Eyes Upward Campaign. Upward, indeed, literally. Some of the campus walks spiraled like goat paths. One stairway had been carved into a rocky cliff, finishing off with what amounted to a gangway, extending 30 feet practically straight up. It was supposed to be a shortcut to the Kessler Science Building and the engineering school but you had to be an Olympic athlete to use it. Most students, as a group more fit (according to comparison tests conducted by the physical performance department) than student bodies elsewhere, still went around the long way or took a mechanical incline. There were four of these old fashioned conveyances spaced across the face of the mountain - a concession preceded by an aching history of dithering among the Board of Trustees. No one really wanted it except the older folk who finally won out in 1952. “It was a college,” one of its more famous graduates famously said, “visualized along the lines of a pirate ship.” Up they went, although there was plenty of room to build along the flats to the west and east of the campus. Wide Tickled Pink / Webster 21 open meadows, orchards and little groves of shady oak and maple, wholly owned by the University, stretched for a hundred acres in all directions but each of the sequential University presidents saw it as a duty to move upward. Of course, many good students passed by the U of Q. On a survey form, there was a special box to check, among others, as the reason for selecting another school: too steep. At the University of Q, they knew who they were. You don't want us, we don't want you, with deeppocketed alumni to back them up. They built complex structures firmly spiked into the side of a mountain. Since the founding, no deaths had resulted from falls. The record is a matter of pride. Steep and safe with but a slight element of risk. It was sometimes proposed, but never adopted, to make the school’s motto: Life and limb – to know.