ACT 220 – Lecture Notes

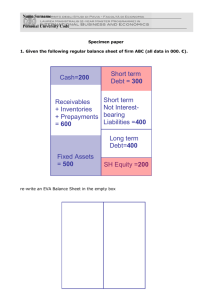

advertisement