7. The French Perspective on European and Global Affairs (2004)

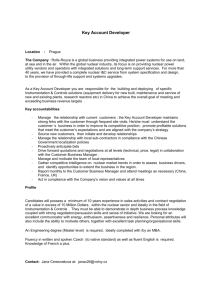

advertisement