As a customer of the U.S. Postal Service, I receive many appeals for

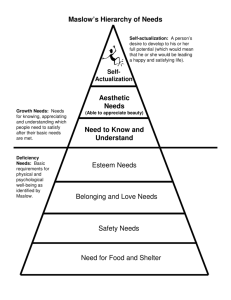

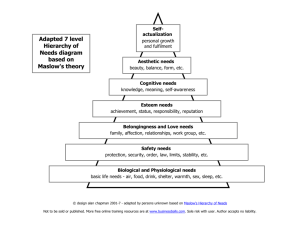

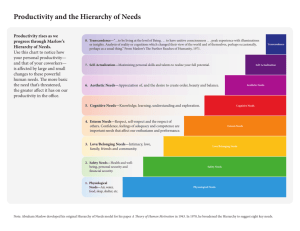

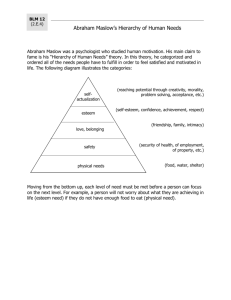

advertisement

As a customer of the U.S. Postal Service, I receive many appeals for donations from a wide variety of charities. I rationalize pushing them aside by telling myself that there are other charitable endeavors that are just as worthy of my money that I don't know about and don't contribute to. I think it takes a particularly well-written appeal to move me to contribute But I've often wondered just how one would go about prioritizing the different situations that charities attempt to address. In other words, how does one decide between contributing money to conserve Rocky Mountain Elk and contributing money for research into prostate cancer. I suppose most contributors to either cause would have some connection to the cause that makes it particularly satisfying for them to be supportive. If you were a hunter who frequented Colorado, you might have encountered literature from a conservation group that merited your attention. Or, you might know someone with prostate cancer and are especially sensitive to efforts to combat it. But would there be any objective, mathematical way to decide? Such a tool might be useful for more objective charitable contributions or for diversifying large-scale contributions. The temptation is to restate our social concerns in terms of their most common denominator: money. Some interesting and important work has been done towards the valuing of ecosystem services in an attempt to put into perspective the value of conservation. It may not cost anything to pollute a stream but how much value does that stream provide in terms of support for wildlife, recreation, aesthetic qualities, etc? The problem with using this approach for social concerns is that because direct aid for the support of human life is involved, in order to compare these endeavors, you have to put a dollar amount on the value of a human being. Impossible. Recently, I've interned with the U.S. Department of Defense. During the holiday season, they offer a very organized approach to charitable giving called the Combined Federal Campaign. The Combined Federal Campaign or CFC is organized of about 300 smaller local units that are comprised of the federal government employers in their respective areas. Each local CFC sends out a list of the approved charities that government employees can choose to donate to. Last fall, I received the 70 page list for the CFC of Monterey and Santa Cruz Counties along with my co-workers. It's a fascinating document. The charities are organized into groups with similar aims such as "Animal Charities" or "Military, Veterans & Patriotic Service Organizations". Each listed charity has a brief description that includes phone number, website, % of budget earmarked for fundraising expenses, and an agency code. It's absolutely overwhelming, how much there is to choose from. I never realized how much diversity there was in non-profit organizations. If my daily mail didn't overwhelm me, I was truly at a loss now. How could one decide among so many appeals that were reduced to tiny equally-advertised appeals? The 70-page list made no distinction between any of the charities. It's a level playing field. It's up to the individual contributor to decide. As I knew that my internship was about to end in a few months anyway, I made no choice. Several months later, while studying for an entrance exam, I re-discovered Abraham Maslow's hierarchy of needs. Maslow proposed in his landmark 1943 paper, “A Theory of Human Motivation”, that as humans meet their basic needs, they seek to satisfy successively higher needs. If this is true, then human needs can be arranged into a general hierarchy. This hierarchy is usually depicted as a pyramid divided into 5 horizontal layers that each symbolize a general category of human needs. The most basic human needs are physiological. The next level of need is to secure that those physiological needs will continue to be met, commonly called “safety” or “security” needs. The next level is social needs – to belong, to be loved. Above that are “esteem” needs – the need for respect or recognition by others. This includes self-respect. The top of the pyramid is usually represented by self-actualization needs. This is the instinctual need of a human to make the most of their unique abilities. Fulfillment of self-actualizing needs is what drives artists and visionaries and “people of purpose”. Not everyone has all of these needs. The needs below them must be met before the needs above them can be realized. But it's a very general principle. The cliché of the “starving artist” would contradict the need hierarchy because the artists physiological need (hunger) should be met before the self-actualizing need (artistic creation) would be realized. But as a very general rule, Maslow's hierarchy of needs seems to make sense. What if Maslow's description of a general hierarchy of human needs could be restated as a prioritization of social concerns? If we project the needs of an individual upon the needs of a human society, we might have a starting point for designing a hierarchy of social concerns. Granted, I'm applying a principle intended to explain individual motivations to society as a whole. But, in a discussion of what our social priorities should be, a good starting point might very well be, “What is most important to all individuals?” Perhaps Maslow's theory of human motivation also serves as a starting point for a theory of social motivation. I use the familiar pyramid diagram of Maslow's hierarchy with the added layer of aesthetic needs that's usually omitted. Maslow originally described this layer in his original paper, but most modern textbook restatements of Maslow's work omit aesthetic needs. One reason for including the aesthetic needs is that Maslow's theory is over 50 years old now and there has been a lot of literature published offering modifications to Maslow's original work. It's enough of a stretch for me to be projecting what was intended as a micro-sociological theory into the macro realm without trying to accommodate the more recent modifications of Maslow's work. If my projection does survive as a viable concept, then which modifications of Maslow's theory might also apply to the projection would be a suitable next question for investigation. Another reason for including the aesthetic needs is the number of charities and social concerns that seem to speak to this level. Recently, I caught a screening of “The Wizard of Oz” on one of the movie channels. In the station's introduction to the film, they featured a spokesperson for a charity that showed classic films in impoverished parts of the world. Their point was that people really do need more than just food and water. Now, given Maslow's pyramid, how can it be used to differentiate between social concerns? If we start with Maslow's original hierarchy and apply a logarithmic scale to each level from the top down, we get these corresponding values at each level of the pyramid: So now, a social need can be assigned a point value based on which level of human need hierarchy that the social concern meets. Each level of need is 10 times greater than the next higher up level of need. The most important needs – the physiological needs – are the 100,000 point level. The least important needs – because they're only realized after all the others are met – are worth 1 point. I realize that I, who was squeamish about even considering what the dollar value of a human life might be, has just implied that the life of one person is worth the aesthetic pleasure of 100,000. Let's hope it never comes to that. Thankfully, there are laws that establish the value of human life above any other consideration. The purpose of this system is to establish a starting point for comparing social concerns, not to decide whether someone should give their life so that 100,000 people can see “The Wizard of Oz”. As an example of how this system might work, I'll compare the social concern of Rocky Mountain Elk conservation with prostate cancer research. The human need that Rocky Mountain Elk meet is largely aesthetic. They are not a keystone species. They are not a primary food source. Their existence provides peace of mind and their hunting provides recreation. I would place the issue of their conservation on the level of an aesthetic need. A need, for sure, but a largely aesthetic one. Now, if we were Rocky Mountain Elk, our conservation would satisfy a physiological need and would be significantly higher valued, but we're not and we won't. Another factor in the value of conservation of a species is the rarity of the species. Conservation of an endangered species would be of greater social concern that conservation of an abundant one. So, I had to find some way of evaluating and ranking the rarity of a species. Deborah Rabinowitz, in her study of English flora, devised a classification system for the rarity of a species that's based on three factors particular to any species population: the geographic range of the species, the habitat tolerance of the species, and the size of the population. She classified rarities into seven categories, one for each combination of the different types. I've simplified this somewhat. If none of these factors are stressed with respect to a species population, that is considered the least critical level of rarity. If any one of these factors is stressed with respect to a species population, that is considered the next level of rarity. Two of the three factors stressed is the next level. All three levels stressed is the most critical level of rarity. Assigning the most critical level of rarity to the full value of the aesthetic need and creating a logarithmic scale again, I came up with this table: 3 factors stressed in the species population = 1 pt. Any 2 factors stressed in the sp. population = 0.1 pt. Any 1 factor stressed in the sp. population = 0.01 pt. No factors stressed in the sp. population = 0.001 pt. Conservation of Rocky Mountain Elk = 0.01 pt. Prostate cancer research meets a safety need near the base of the hierarchy. Prostate cancer can be a matter of life and death. But at that point, research for a better treatment isn't going to help much. I therefore, put the research into a safety category because its goal is to avoid the physiological attack that the cancer represents. Prostate cancer research = 10,000 pts. I can already hear the cheers of prostate cancer sufferers. Now, I do realize that many Rocky Mountain Elk enthusiasts are also hunters and that most hunters are well armed and can look up my address on the internet. Please unload and bear with me. Let's look at the numbers of people affected. Who does the conservation of rocky mountain elk affect? Who are the stakeholders in the existence of Rocky Mountain Elk? Well, most of the range of the Rocky Mountain Elk is under the sovereignty of either the United States or Canada. Are their total populations the stakeholders? Are the states and provinces the rightful sovereigns where the ranges are located? Are their populations the actual stakeholders? Does someone living outside of the United States or Canada have any claim to the existence of Rocky Mountain Elk? I think so. I think that someone living in Australia can appreciate the beauty of an Elk just as much as the homeowner whose backyard it's standing in. I think that an Australian's aesthetic need is on an equal par with anyone else's on earth. I'm sure Australia needed me to tell them that. An aesthetic need is an aesthetic need. It doesn't matter to the individual which government they are ruled by or how much land they own. Nations who shelter the biota of the world within their borders have a responsibility to the rest of humanity to preserve that biodiversity. Millions of people affected by Rocky Mountain Elk conservation = 6529.2 According to the Prostate Cancer Foundation, 1 in 6 American men will get prostate cancer. U.S. population of 293 million divided by 2 (males) and then divided by 6 (prostate cancer sufferers) Millions of people affected by prostate cancer research = 24.7 If we multiply the value of the social concern by the number of people affected, we should get some kind of ballpark figure for how important these two social concerns are in relation to each other. Rocky Mountain Elk conservation Millions of stakeholders X value as a social concern = 6529.2 X .01 = 65.3 Prostate cancer research Millions of stakeholders X value as a social concern = 24.7 X 10,000 = 247,000 If we convert these values to a scale where the power of ten is the ones place and the leading digits of the value follow, starting with the tenths place, we get: Rocky Mountain Elk conservation = 1.6 Prostate cancer research = 5.2 And the Elk hunters who don't have prostate cancer can finish looking up my address on the internet. This system, of course, seems ridiculous if your either of these concerns is higher or lower in your personal hierarchy of needs than the completely stratified, completely objective, dummy hierarchy used to develop the system. You might also be offended at the idea of resolving complex, sensitive, critical social concerns to a mere number. It seems cold and inhuman to me, too. I have a nightmare of some executive looking up values in a book and deciding not to donate a million dollars to Jerry's kids this year because the preservation of golf courses scored higher according to certain formulae. That's a gross exaggeration, but I think it's the kind of evil that I worry might be made of this. Indeed, it's the kind of scenario that I hope to combat with a system like this. Most people will not have any use for a system like this to tell them that Elk are more important that prostates, or vice versa. What I envision this system being applied to is lists of charities such as the ones published by the various Combined Federal Campaigns, to add another parameter to help people decide between charities. There are a number of organizations that track how efficiently a charity spends it's money, persists in it's activities during economic stress, fundraises, etc. Their rankings of the best charities to contribute to seem stacked in favor of universities, scholarship programs, police departments. These are all worthy concerns but I worry that our inability to prioritize social concerns as easily as financial ones leads to the skewing of these rankings in favor of the financially stable and at the expense of the financially needy Another problem with this system is that there are levels of severity within a general concern that requires additional research or expertise. In this example, ranking the rarity of a particular species was a problem that necessitated, at least cursory, further research. I would anticipate similar problems in dealing with diseases and cultural preservation issues. But, if numerical comparisons of social concerns is as basic to your personal hierarchy of needs as it is to mine, you might find this a useful starting point for the evaluation of which concerns most merit your charitable contributions or your volunteer time. I've evaluated the first two. I have about 3000 more to do before I'm ready for this years' "giving season".