Canada's Role in the League of Nations

advertisement

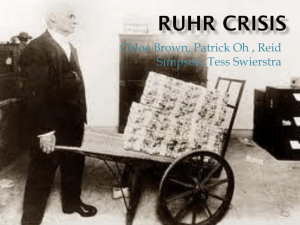

Canada’s Role in the League of Nations The hope of ensuring that World War I would become ”the war to end all wars” led to the creation of the League of Nations. Through the untiring efforts of Woodrow Wilson, the U.S. President, the terms crating the League were written into the Treaty of Versailles. The League of Nations was based upon the principles of “collective Security.” All members ere to co-operate against the outbreak of war. If the security (peace) of any member were threatened, the others were to assist in preventing war. Discussion, rather than war was to be the goal of these cooperating nations. An International Court of Justice was set up as a world court to pass judgments on disagreements between League members. Further, the League had as a long-range goal eventual world disarmament (doing away with weapons of war). The Constitution of the League, to be realistic, had to provide t least some measures stronger than discussion. To give the League some “teeth” for stopping small wars from spreading, members of the League had to agree to: - Article X, under which members were asked to respect and help to protect the independence of all nations from invasion or conquest by any other nation. - Article XVI, under which member nations from invasion or all products sold by any nation at war other than to defend itself. Most importantly, League members promised not to sell any products to the aggressor in a war situation. In practice, most nations tried to avoid “Getting involved” in actions against those who threatened world peace. Canada was one of the countries most critical of Article X. The Canadian delegates to the League claimed that Article X was an unreasonable obligation for a country located in the “peaceful” Western Hemisphere (after all, the first World war was really only a “European” war, claimed Canada). The Canadian representative to the League, Raoul Dandurand, compared Canada and the U.D. to two neighbours, one of which was a fireman; “May I be permitted to add that in this association of mutual insurance against fire (war), that the risks we face are not all equal. We (Canada) live in a fire-proof house, far from inflammable materials. A vast ocean separates us from Europe.” The decision of the United States not to join the League came as a severe blow to Canada. Americans had been disillusioned by their brief participation in the “European War” and rejected President Wilson’s vision of America as a policeman in world diplomacy. The Congress of the U.S.A. voted to not participate in the League (a crushing blow to President Wilson, who had worked so hard to create the League) and instead chose the path of “isolationism”. This left Canada in the undesirable position as a kind of representative of all North America. She feared that she might get dragged into overseas wars, perhaps without the support of her powerful neighbor (the “fireman”). THE ETHIOPIAN CRISIS OF 1935 While Adolf Hitler was restoring German military might, his Fascist ally to the South, the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, had decided that his nation’s destiny lay in recapturing the glory of the ancient Roman Empire. In the spring of 1935 Italian armies invaded the weak African nation of Ethiopia (see map). Italian war ships were allowed to pass unchallenged through the Suez Canal in 1936. By 1936 Italy had conquered Ethiopia and Emperor Hailie Selassie had to flee his country. Mussolini had said earlier (1935): “If the League had extended its embargo to include oil, I would have had to withdraw from Ethiopia in a week.” Armed with spears and shields, the subjects of Ethiopia’s Emperor Hailie Selassie fought vainly against tanks, airplanes, and heavily armed troops. The League of Nations met hastily and “condemned” Italy for the attack. An embargo (boycott) on trade was approved, despite the fact that the League had not banned trade with more powerful nation of Japan during its invasion of Manchuria. However, the League did not go far enough in its boycott of trade with Italy, and it soon had to consider more drastic action. It was at this point that Canada became involved. Mussolini’s war machine depended heavily upon imported oil, and a complete ban on trade by the League could have forced Italy to stop almost immediately. However, even Great Britain and France held back from so forceful a decision. Canada’s representative to the League, W. A. Riddell, boldly proposed that oil be added to the list of goods not to be traded to Italy. The Canadian government was in the midst of an election in 1935 (Mackenzie King defeated R. B. Bennet). Forced by circumstances to act on his own (there was no Prime Minister to take commands from), Riddell hoped that his suggestion would bring peace to Ethiopia. The new Prime Minister of Canada, Mackenzie King, promptly dismissed Riddell’s action as a personal decision, and assured the League that it was not the policy of Canada: “What was my amazement when on reading the morning paper I found that Dr. Riddell at Geneva was reported to have to be prohibited from export to Italy. No instructions whatever had been sent to him from Ottawa authorizing anything of the kind. Word was immediately sent that no action of any kind was to be taken by Doctor Riddell without specific instructions from this government.” News of the “Canadian proposal” as it was described by the European press, ignited furious argument in Canada. Catholic Quebec, where there was sympathy for Italy, the home of the Pope, charged that the League’s pressure on Italy was a maneuver by Protestant Britain. Canadian public opinion was divided, and Mackenzie King feared taking a stand that would antagonize the people. Neither Great Britain within the League nor the United States outside the League seemed willing to take the risks needed to stop the Italians. The Canadian Prime Minister, then, refused a leadership role for his country. Although insisting that Canada would co-operate in any decisions the League made, Mackenzie King declared that Riddell’s idea was not the policy of the Canadian government. The rest of the League members seemed to take their cue from Canada, although it is likely they would have come to the same decision regardless, and the proposed boycott of oil was dropped. Whatever the explanation the League of Nations had failed at its moment of greatest challenge. If a “paper tiger” like Mussolini could ignore the League and flaunt world opinion, what might happen with an even more belligerent government wielding even greater military strength? QUESTIONS (to be answered in notebook) 1. Why did many nations (especially Canada) object the Article X of the League of Nations’ constitution? 2. Why was Canada unhappy when the U.S. A. did not join the League? 3. Explain what Raoul Dandurand means in his story about firemen and fireproof houses. 4. How would you describe Mackenzie King’s actions following Riddell’s suggestions about adding oil to the embargo list? 5. a) What were the League’s obvious weaknesses? (think of several) b) Which of these do you feel is the most serious? (that is, which one doomed the League to failure as a collective security organization?) EXPLAIN.