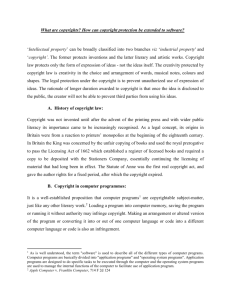

Costar Group v. Loopnet, Inc., 2001 U.S. Dist. Lexis 15401 (Sept. 28

advertisement