Children's Speech

Sound Disorders

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

Copyright © 1998 Caroline Bowen All rights

reserved

Citing this article

This page contains an article about

children's speech sound

disorders. Cite it as:

Bowen, C. (1998). Children's speech sound

disorders: Questions and answers. Retrieved from

http://www.speech-languagetherapy.com/phonol-and-artic.htm on (date).

Introduction

What is speech?

Speech is the spoken medium of language. The other two "mediums" or "forms" of

language are writing and gestures. Gestures range from simple iconic movements,

like pretending to drink, through to complex finger-spelling and sign systems.

What is phonology?

Phonology is a branch of linguistics. It is concerned with the study of the sound

systems of languages.

The aims of phonology are to demonstrate the patterns of distinctive sound contrasts

in a language, and to explain the ways speech sounds are organised and represented

in the mind.

The term "phonology" is used clinically as a referent to an individual’s speech sound

system - for example, "her phonology" might refer to "her phonological system", or

"her phonological development".

What is phonological development?

The gradual process of acquiring adult speech patterns is called phonological

development.

Putting it another way, the emergence in children of a properly organised speech

sound system is called phonological development.

Phonological development involves three aspects:

the way the sound is stored in the child’s mind;

the way the sound is actually said by the child;

the rules or processes that map between the two above.

How easy should it be to understand young children's speech?

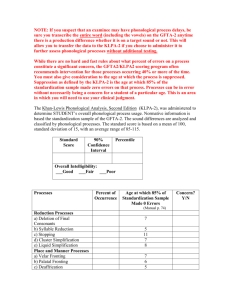

Table 1 provides a rough rule of thumb for how clearly your child should be

speaking. Bear in mind that there is considerable individual variation between

children. If you are in doubt about your own child's speech sound development an

assessment by a speech-language pathologist will quickly tell you if your child is 'on

track' and making the right combination of correct sounds and 'errors' for their age.

TABLE 1: How well words can be

understood by parents

By 18 months a child's speech is normally

25% intelligible

By 24 months a child's speech is normally

50 -75% intelligible

By 36 months a child's speech is normally

75-100% intelligible

Lynch, Brookshire & Fox (1980), p. 102, cited in Bowen

(1998).

Intelligibility to Parents

(18-36 months)

Table 1, above, provides a rough rule of

thumb for how clearly a child should be

speaking in the age-range 18 to 36

months. It is important to bear in mind

that there is considerable individual

variation between children. If, as a

parent, you are in doubt about your own

child's speech sound development or

speech clarity, an assessment by a

speech-language pathologist will quickly

tell you if your child is 'on track' and

making the right combination of correct

sounds and 'errors' for their age

What are the characteristics of young children's speech?

All children make predictable pronunciation errors (not really 'errors' at all, when you

stop to think about it) when they are learning to talk like adults. These 'errors' are

called phonological processes, or phonological deviations. Table 2 displays the

common phonological processes found in children's speech while they are learning

the adult sound-system of English. Further detail is provided on the typical speech

acquisition page.

Phonological Processes

COPYRIGHT 1999 CAROLINE BOWEN

All children make predictable pronunciation errors (not really 'errors' at all, when you

stop to think about it) when they are learning to talk like adults. These 'errors' are

called phonological processes, or phonological deviations. In Table 2 are the common

phonological processes found in children's speech while they are learning the adult

sound-system of English.

TABLE 2: Phonological Processes in Typical Speech Development

PHONOLOGICAL

PROCESS (Phonological

Deviation)

EXAMPLE

DESCRIPTION

Context sensitive voicing

"Pig" is pronounced and "big"

A voiceless sound is replaced by a

voiced sound. In the examples given, /p/

is replaced by /b/, and /k/ is replaced by

/g/. Other examples might include /t/

being replaced by /d/, or /f/ being

replaced by /v/.

"Car" is pronounced as "gar"

Word-final devoicing

"Red" is pronounced as "ret"

"Bag" is pronounced as "bak"

Final consonant deletion

"Home" is pronounced a "hoe"

"Calf" is pronounced as "cah"

Velar fronting

"Kiss" is pronounced as "tiss"

"Give" is pronounced as "div"

"Wing" is pronounced as "win"

Palatal fronting

"Ship" is pronounced as "sip"

"Measure" is pronounced as

"mezza"

Consonant harmony

"Cupboard" is pronounced as

"pubbed"

A final voiced consonant in a word is

replaced by a voiceless consonant.

Here, /d/ has been replaced by /t/ and /g/

has been replaced by /k/.

The final consonant in the word is

omitted. In these examples, /m/ is

omitted (or deleted) from "home" and /f/

is omitted from "calf".

A velar consonant, that is a sound that is

normally made with the middle of the

tongue in contact with the palate towards

the back of the mouth, is replaced with

consonant produced at the front of the

mouth. Hence /k/ is replaced by /t/, /g/ is

replaced by /d/, and 'ng' is replaced by

/n/.

The fricative consonants 'sh' and 'zh' are

replaced by fricatives that are made

further forward on the palate, towards

the front teeth. 'sh' is replaced by /s/,

and 'zh' is replaced by /z/.

The pronunciation of the whole word is

influenced by the presence of a

particular sound in the word. In these

"dog" is pronounced as "gog"

Weak syllable deletion

Telephone is pronounced as

"teffone"

"Tidying" is pronounced as

"tying"

Cluster reduction

"Spider" is pronounced as

"pider"

"Ant" is pronounced as "at"

Gliding of liquids

"Real" is pronounced as "weal"

"Leg" is pronounced as "yeg"

Stopping

"Funny" is pronounced as

"punny"

"Jump" is pronounced as "dump"

examples: (1) the /b/ in "cupboard"

causes the /k/ to be replaced /p/, which

is the voiceless cognate of /b/, and (2)

the /g/ in "dog" causes /d/ to be replaced

by /g/.

Syllables are either stressed or

unstressed. In "telephone" and "tidying"

the second syllable is "weak" or

unstressed. In this phonological process,

weak syllables are omitted when the

child says the word.

Consonant clusters occur when two or

three consonants occur in a sequence in

a word. In cluster reduction part of the

cluster is omitted. In these examples /s/

has been deleted form "spider" and /n/

from "ant".

The liquid consonants /l/ and /r/ are

replaced by /w/ or 'y'. In these examples,

/r/ in "real" is replaced by /w/, and /l/ in

"leg" is replaced by 'y'.

A fricative consonant (/f/ /v/ /s/ /z/, 'sh',

'zh', 'th' or /h/), or an affricate consonant

('ch' or /j/) is replaced by a stop

consonant (/p/ /b/ /t/ /d/ /k/ or /g/). In

these examples, /f/ in "funny" is replaced

by /p/, and 'j' in "jump" is replaced by

/d/.

Typical Speech Development

THE GRADUAL ACQUISITION OF THE SPEECH SOUND SYSTEM

Copyright © Caroline Bowen 1998 All rights reserved

Citing this article

This page contains an article about speech development. Cite it as: Bowen, C. (1998).

Typical speech development: the gradual acquisition of the speech sound system.

Retrieved from http://www.speech-language-therapy.com/acquisition.html on (date).

Anyone who has been around children who are under 5 years of age will

know that their speech sounds are not pronounced correctly all the time.

In fact a small, typically developing child's speech can be quite difficult to

understand because his or her sound system is not yet organised like adult

speech.

Articulation and Phonology Norms

Many researchers have studied children's acquisition of individual speech

sounds (phonetic development), and the way they organise these sounds

into speech patterns (phonemic or phonological development). Drawing on

this vast a varied body of research, Dr Sharynne McLeod of Charles Sturt

University in Australia compiled the pdf file here,[Adobe Reader

Required]. It contains an overview of typical speech development from a

range of researchers around the world, working from a variety of

theoretical perspectives.

Developmental norms and target selection

Gregory L. Lof PhD presented a fascinating poster entitled Confusion

about speech sound norms and their use in an online conference

sponsored by Thinking Publications in 2004, exploding a few myths about

normal (or 'normative') expectations and when to start therapy for

particular speech sounds.

Critical information

For Speech-Language Pathologists providing assessment and intervention

for Speech Sound Disorders, a detailed understanding of typical

('normal') development is critical to the understanding of delayed and

disordered development.

Intelligibility

Table 1 provides a rough rule of thumb for how clearly your child should

be speaking. If you are in doubt about your own child's speech sound

development an assessment by a speech-language pathologist will quickly

tell you if your child is 'on track' and making the right combination of

correct sounds and 'errors' for their age. Table 1 is available separately

here. See also: speech intelligibility from 12 to 48 months for a more

detailed discussion.

TABLE 1: How well words can be understood by parents

By 18 months a child's speech is normally 25% intelligible

By 24 months a child's speech is normally 50 -75% intelligible

By 36 months a child's speech is normally 75-100% intelligible

Source: Lynch, J.I., Brookshire, B.L., and Fox, D.R. (1980). A Parent - Child Cleft Palate Curriculum: Developing

Speech and Language. CC Publications, Oregon. Page 102

Phonological development

The gradual process of acquiring adult speech patterns is called

phonological development.

Phonological processes

All children make predictable pronunciation errors (not really 'errors' at all,

when you stop to think about it) when they are learning to talk like adults.

These 'errors' are sometimes called phonological processes, or

phonological deviations.

In Table 2 are the common phonological processes found in children's

speech while they are learning the adult sound-system of English. Table 2

is available separately here.

TABLE 2: Phonological Processes in Normal Speech Development

PHONOLOGICAL

PROCESS

(Phonological

Deviation)

EXAMPLE

DESCRIPTION

Context sensitive "Pig" is pronounced and "big" A voiceless sound is replaced

voicing

by a voiced sound. In the

"Car" is pronounced as "gar" examples given, /p/ is replaced

by /b/, and /k/ is replaced by /g/.

Other examples might include /t/

being replaced by /d/, or /f/

being replaced by /v/.

Word-final

devoicing

"Red" is pronounced as "ret"

Final consonant

deletion

"Home" is pronounced a "hoe" The final consonant in the word

is omitted. In these examples,

"Calf" is pronounced as "cah" /m/ is omitted (or deleted) from

"home" and /f/ is omitted from

"calf".

Velar fronting

"Kiss" is pronounced as "tiss" A velar consonant, that is a

sound that is normally made

"Give" is pronounced as "div" with the middle of the tongue in

contact with the palate towards

the back of the mouth, is

"Wing" is pronounced as "win"

replaced with consonant

produced at the front of the

mouth. Hence /k/ is replaced by

/t/, /g/ is replaced by /d/, and 'ng'

is replaced by /n/.

Palatal fronting

"Ship" is pronounced as "sip"

A final voiced consonant in a

word is replaced by a voiceless

"Bag" is pronounced as "bak" consonant. Here, /d/ has been

replaced by /t/ and /g/ has been

replaced by /k/.

"Measure" is pronounced as

"mezza"

Consonant

harmony

The fricative consonants 'sh'

and 'zh' are replaced by

fricatives that are made further

forward on the palate, towards

the front teeth. 'sh' is replaced

by /s/, and 'zh' is replaced by

/z/.

"Cupboard" is pronounced as The pronunciation of the whole

"pubbed"

word is influenced by the

presence of a particular sound

"dog" is pronounced as "gog" in the word. In these examples:

(1) the /b/ in "cupboard" causes

the /k/ to be replaced /p/, which

is the voiceless cognate of /b/,

and (2) the /g/ in "dog" causes

/d/ to be replaced by /g/.

Weak syllable

deletion

Telephone is pronounced as

"teffone"

"Tidying" is pronounced as

"tying"

Cluster reduction "Spider" is pronounced as

"pider"

"Ant" is pronounced as "at"

Gliding of liquids

"Real" is pronounced as

"weal"

"Leg" is pronounced as "yeg"

Stopping

"Funny" is pronounced as

"punny"

"Jump" is pronounced as

"dump"

Syllables are either stressed or

unstressed. In "telephone" and

"tidying" the second syllable is

"weak" or unstressed. In this

phonological process, weak

syllables are omitted when the

child says the word.

Consonant clusters occur when

two or three consonants occur

in a sequence in a word. In

cluster reduction part of the

cluster is omitted. In these

examples /s/ has been deleted

form "spider" and /n/ from "ant".

The liquid consonants /l/ and /r/

are replaced by /w/ or 'y'. In

these examples, /r/ in "real" is

replaced by /w/, and /l/ in "leg" is

replaced by 'y'.

A fricative consonant (/f/ /v/ /s/

/z/, 'sh', 'zh', 'th' or /h/), or an

affricate consonant ('ch' or /j/) is

replaced by a stop consonant

(/p/ /b/ /t/ /d/ /k/ or /g/). In these

examples, /f/ in "funny" is

replaced by /p/, and 'j' in

"jump" is replaced by /d/.

Elimination of phonological processes

Phonological processes have usually 'gone' by the time a child is five

years of age, though there is individual variation between children.

Table 3 lists the ages by which each of the processes are normally

eliminated. Ages are expressed as years;months. For example, 3;6

means 3 years 6 months. Table 3 is available separately here.

TABLE 3: Ages by which Phonological Processes are Eliminated

PHONOLOGICAL PROCESS

EXAMPLE

GONE BY

APPROXIMATELY

years ; months

Context sensitive voicing

pig = big

3;0

Word-final de-voicing

pig = pick

3;0

Final consonant deletion

comb = coe

3;3

Fronting

car = tar

3;6

ship = sip

Consonant harmony

mine = mime

kittycat = tittytat

3;9

Weak syllable deletion

elephant = efant

potato = tato

television =tevision

banana = nana

4;0

Cluster reduction

spoon = poon

train = chain

clean = keen

4;0

Gliding of liquids

run = one

leg = weg

leg = yeg

5;0

Stopping /f/

fish = tish

3;0

Stopping /s/

soap = dope

3;0

Stopping /v/

very = berry

3;6

Stopping /z/

zoo = doo

3;6

Stopping 'sh'

shop = dop

4;6

Stopping 'j'

jump = dump

4;6

Stopping 'ch'

chair = tare

4;6

Stopping voiceless 'th'

thing = ting

5;0

Stopping voiced 'th'

them = dem

5;0

Phonetic development

Table 4 outlines the ages by by which 75% of children in a carefully conducted

study accurately use individual speech sounds in single test-words. These

norms were established for a population of Australian children by Kilminster

and Laird (1978).

In column 3, the term 'voiced' refers to the vibration of the vocal cords while

the sound is being made. The term 'voiceless' is applied to sounds that are

made without vocal cord vibration. The terms fricative, glide, stop, nasal, liquid

and affricate refer to the way the sounds are made, or the "manner of

articulation". The International Phonetic Alphabet Charts summarise this

information here. Table 4 is available separately here.

Table 4: Normal phonetic development

Column 1

Column 2

Ages by which 75% of children Speech sounds

tested in a study accurately

used the speech sounds listed

in Column 2 in single words.

Column 3

The manner in

which the speech

sounds are

produced

3 years

Voiceless fricative

h as in he

zh as in measure

Voiced fricative

y as in yes

Voiced glide

w as in we

Voiced glide

ng as in sing

Voiced nasal

m as in me

Voiced nasal

n as in no

Voiced nasal

p as in up

Voiceless stop

k as in car

Voiceless stop

t as in to

Voiceless stop

b as in be

Voiced stop

g as in go

Voiced stop

d as in do

Voiced stop

3 years 6 months

f as in if

Voiceless fricative

4 years

l as in lay

Voiced liquid

sh as in she

Voiceless fricative

ch as in chew

Voiceless affricate

j as in jaw

Voiced affricate

s as in so

Voiceless fricative

z as in is

Voiced fricative

5 years

r as in red

Voiced liquid

6 years

v as in Vegemite

Voiced fricative

8 years

th as in this

Voiced fricative

8 years 6 months

th as in thing

Voiceless fricative

4 years 6 months

References

Bowen, C, (1998). Developmental phonological disorders. A practical guide

for families and teachers. Melbourne: ACER Press.

Grunwell, P. (1997). Natural phonology. In M. Ball & R. Kent (Eds.), The new

phonologies: Developments in clinical linguistics. San Deigo: Singular

Publishing Group, Inc.

Kilminster, M.G.E., & Laird, E.M. (1978) Articulation development in children

aged three to nine years. Australian Journal of Human Communication

Disorders, 6, 1, 23-30.

Lof, G.L. (2004). Confusion about speech sound norms and their use.

Thinking Publications Online Conference.

www.thinkingpublications.com/LangConf04/OLCIntro.html Accessed April 21

2004.

Lynch, J.I., Brookshire, B.L., & Fox, D.R. (1980). A Parent - Child Cleft Palate

Curriculum: Developing Speech and Language. CC Publications, Oregon.

Child speech professional discussion

Phonological Therapy is a discussion group for clinicians, including student

clinicians, speech and language researchers and university teachers. Most

participants are Speech-Language Pathologists and Linguists. Members explore

theoretical and research issues related to developmental phonological

disorders, childhood apraxia of speech, and other childhood speech sound

disorders, and their clinical management. Although interested consumers are

most welcome to join, please note that the group is for professional discussion

not consumer advice and support.

By what ages are phonological processes typically eliminated?

Phonological processes have usually 'gone' by the time a child is five years of age,

though there is individual variation between children. Table 3 lists the ages by

which each of the processes are normally eliminated.

Phonological

Development

THE GRADUAL ACQUISITION OF THE

SPEECH SOUND SYSTEM

COPYRIGHT 1999

CAROLINE BOWEN

TABLE 3: Elimination of Phonological

Processes

Phonological processes are typically gone by these ages (in

years ; months)

PHONOLOGICAL

PROCESS

EXAMPLE

Context

pig = big

GONE BY

APPROXIMATELY

3;0

sensitive

voicing

Word-final devoicing

pig = pick

3;0

Final

consonant

deletion

comb =

coe

3;3

Fronting

car = tar

ship = sip

3;6

Consonant

harmony

mine =

mime

kittycat =

tittytat

3;9

Weak syllable

deletion

elephant =

efant

potato =

tato

television

=tevision

banana =

nana

4;0

Cluster

reduction

spoon =

poon

train =

chain

clean =

keen

4;0

Gliding of

liquids

run = one

leg = weg

leg = yeg

5;0

Stopping /f/

fish = tish

3;0

Stopping /s/

soap =

dope

3;0

Stopping /v/

very =

berry

3;6

Stopping /z/

zoo = doo

3;6

Stopping 'sh'

shop =

dop

4;6

Stopping 'j'

jump =

dump

4;6

Stopping 'ch'

chair =

tare

4;6

Stopping

thing =

5;0

voiceless 'th'

ting

Stopping

voiced 'th'

them =

dem

5;0

What is articulation?

Articulation is a general term used in phonetics to denote the physiological

movements involved in modifying the airflow, in the vocal tract above the larynx, to

produce the various speech sounds. Sounds are classified according to their place

and manner of articulation in the vocal mechanism (Crystal,1991).

VPM

VOICE-PLACE-MANNER

of articulation

In the International Phonetic Alphabet consonant (pulmonic) chart you will see that

eleven places of articulation are displayed: bilabial (consonants made with both lips

in contact); labiodental (consonants made with contact between the lower lip and

upper teeth); and so on.

These places of articulation are cross referenced with the way, or manner in which

the sounds are produced. There are eight manners of articulation: plosive (or stop)

consonants in which the air-flow is stopped abruptly by the articulators; nasals, in

which the air flows down the nose; fricatives in which friction is created by the air

passing through lightly touching articulators; and so on.

The chart also indicates which consonants are voiced (like b, d, g, v, z, etc.) and

which are voiceless (like p, t, k, f, s, etc.). Where you see pairs of sounds (or

voiced and voiceless cognates) the voiceless sound is on the left, and the voiced one

on the right. When a voiced sound is produced the vocal cords in the larynx (voice

box) vibrate. When a voiceless sound is produced the vocal cords do not vibrate.

All the consonants of English can be classified in terms of "VPM" (voice-placemanner). For instance, /f/ is a voiceless labiodental fricative, and /b/ is a voiced

bilabial plosive (stop).

Click here for the 2005 version of the full chart

The International Phonetic Alphabet may be freely copied on condition that acknowledgement is made to the International

Phonetic Association (Department of Theoretical and Applied Linguistics, School of English, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki,

Thessaloniki 54124, GREECE).

Page updated

What are articulation development and phonetic development?

The terms 'articulation development' and 'phonetic development' both refer to

children's gradual acquisition of the ability to produce individual speech sounds. In

Table 4 is an outline the ages by which children use individual consonants with 75%

accuracy during conversation. more here

Phonetic Development

COPYRIGHT 1999 CAROLINE BOWEN

Table 4 outlines the ages by which 75% of the children in a study pronounced

individual consonants accurately. These norms were established for a population of

Australian children by Kilminster and Laird (1978).

In column 3, the term 'voiced' refers to the vibration of the vocal cords while the

sound is being made. The term 'voiceless' is applied to sounds that are made without

vocal cord vibration. The terms fricative, glide, stop, nasal, liquid and affricate refer

to the way the sounds are made, or the "manner of articulation". The International

Phonetic Alphabet Charts summarise this information here.

Table 4: Typical phonetic development

Age by which 75% of children

accurately use the speech

sound listed

Speech sounds

The manner in which the

speech sounds are produced

3 years

h as in he

Voiceless fricative

zh as in measure

Voiced fricative

y as in yes

Voiced glide

w as in we

Voiced glide

ng as in sing

Voiced nasal

m as in me

Voiced nasal

n as in no

Voiced nasal

p as in up

Voiceless stop

k as in car

Voiceless stop

t as in to

Voiceless stop

b as in be

Voiced stop

g as in go

Voiced stop

d as in do

Voiced stop

f as in if

Voiceless fricative

3 years 6 months

4 years

l as in lay

Voiced liquid

sh as in she

Voiceless fricative

ch as in chew

Voiceless affricate

j as in jaw

Voiced affricate

s as in so

Voiceless fricative

z as in is

Voiced fricative

5 years

r as in red

Voiced liquid

6 years

v as in Vegemite

Voiced fricative

8 years

th as in this

Voiced fricative

8 years 6 months

th as in thing

Voiceless fricative

4 years 6 months

References

Bowen, C. (1998). Developmental phonological disorders. A practical guide for

families and teachers. Melbourne: ACER Press.

.

Grunwell, P. (1997). Natural phonology. In M. Ball & R. Kent (Eds.), The new

phonologies: Developments in clinical linguistics. San Deigo: Singular Publishing

Group, Inc.

.

Kilminster, M.G.E., & Laird, E.M. (1978) Articulation development in children aged

three to nine years. Australian Journal of Human Communication Disorders, 6, 1, 2330.

The difference between an

articulation disorder and a

phonological disorder

Copyright 2002 Caroline

Bowen

Citing this article

This page contains an article about

speech disorders. Cite it as:

Bowen, C. (2002). The difference between an

articulation disorder and a phonological disorder.

Retrieved from www.speech-languagetherapy.com/phonetic_phonemic.htm on (date).

Familiar questions

A question from the parent of a four

year old with difficult-to-understand

speech:

What is the difference between an

articulation disorder and a phonological

disorder? How can you tell the difference?

Are they treated differently?

A question from a colleague:

Although I have been a school-based SLP

for over 20 years I have to say I am

confused about the distinction between

phonetic speech sound disorders, and

phonemic speech sound disorders. In

simple terms, what exactly is the

difference?

Speech

Speech is the spoken medium of

language. Speech has a phonetic level and

a phonological (or phonemic) level.

Phonetic (articulation) level

The phonetic level takes care of the motor

act of producing the vowels and

consonants, so that we have a repertoire

all the sounds we need in order to speak

our language.

Phonological (phonemic) level

The phonological or phonemic level is in

charge of the brainwork that goes into

organising the speech sounds into

patterns of sound contrasts so that we can

make sense when we talk.

Articulation (phonetic) disorder

In essence, an articulation disorder is a

SPEECH disorder that affects the

PHONETIC level. The child has difficulty

saying particular consonants and vowels.

The reason for this may be unknown (e.g.,

children with functional speech

disorders who do NOT have serious

problems with muscle function); or the

reason may be known (e.g., children with

dysarthria who DO have serious problems

with muscle function).

Typical speech development

Speech-Language Pathologists make a

detailed study of all aspects of normal

human communication and its

development in the areas of voice,

speech, language, fluency and

pragmatics. A thorough knowledge and

understanding of what science reveals

about typical speech development is

critical to our understanding of children's

speech sound disorders.

Language

Language has been called the

symbolisation of thought. It is a learned

code, or system of rules that enables us to

communicate ideas and express wants

and needs. Reading, writing, gesturing

and speaking are all forms of language.

Language falls into two main divisions:

receptive language (understanding what is

said, written or signed); and, expressive

language (speaking, writing or signing).

Phonological disorder

A phonological disorder is a LANGUAGE

disorder that affects the PHONOLOGICAL

(phonemic) level. The child has difficulty

organising their speech sounds into a

system of sound contrasts (phonemic

contrasts).

What is the difference

between an articulation

disorder and a

phonological disorder?

In an articulation disorder the child's

difficulty is at a phonetic level. That is,

they have trouble making the individual

speech sounds.

In a phonological disorder the child's

difficulty is at a phonemic level (in the

mind). This "phonemic level" is sometimes

referred to as "the linguistic level" or "a

cognitive level".

Co-occurrence

An articulation disorder and a phonological

disorder can co-occur. That is, the same

child can have BOTH.

Assessment and diagnosis

Because of their knowledge-base, SpeechLanguage Pathologists (SLPs) are able to

distinguish between the many speech and

language disorders they have to assess

(or "differentially diagnose") in the course

of their work.

The assessment process typically involve

screening the child's communication skills

in a general way, and then forming an

hypothesis about the nature of any

apparent difficulties.

If speech clarity is a problem the SLP will

examine both the PHONETIC and the

PHONOLOGICAL aspects of the child's

speech. The tests chosen will depend on

the child's presentation and the theoretical

beliefs of the clinician.

Use of terminology

Some SLPs use the term "articulation

disorder" very loosely, especially when

they are explaining these complex ideas

to people who do not have a background

in linguistics or speech pathology. Indeed,

they may refer to a "phonological

disorder" as an "articulation disorder".

It can often be quite helpful for parents to

ask their SLP what they mean by the

particular terms they use.

"Functional"?

The term "functional" speech disorder' is

usually equated with the concept of

"cause unknown" and these disorders are

often referred to as speech disorders of

unknown origin.

Although we cannot "prove" or

"demonstrate" what has "caused" a

speech sound disorder in a particular

child, we can often form justifiable

hypotheses regarding the likely cause,

given a child's history (Flipsen, 2002).

Factors such as family history, frequent

otitis media, developmental apraxia of

speech, and psychosocial factors

(Shriberg, 1993) may be considered.

Developmental?

The word "developmental" in

"developmental phonological disorders",

"developmental dysarthria", and

"developmental apraxia of speech" (the

preferred term is "childhood apraxia of

speech") simply denotes that the

disorders occur in children. The word

"developmental" is not appended to

functional speech disorders, which occur

in both children and adults.

Intervention

There is information about the treatment

of children's speech sound disorders here.

Discussion

The phonological therapy discussion

group provides communication disorders

professionals with an opportunity to ask

and answer questions and explore

theoretical and research issues related to

young children's speech sound disorders

in general, and developmental

phonological disorders, articulation

disorders, and developmental apraxia of

speech in particular. The emphasis is on

theoretically sound, evidence-based

clinical assessment and intervention

How are phonological and phonetic development related?

There is a complex relationship between phonological and phonetic development.

Normal speech development involves learning both phonetic and phonological

features.

The bulk of recent research into children’s speech development has dealt with

phonology: exploring and attempting to explain the process of the elaboration of

speech output into a system of contrastive sound units. In recent years, there has

also been a considerable body of research into the acquisition of motor speech

control, bringing with it a renewed interest in the nexus between phonological

development and phonetic development.

Phonological development and phonetic mastery do not synchronise precisely. A

common example of this asynchrony, referred to by Smith (1973) as the puzzle

phenomenon, is provided by children who realise /s/ and /z/ as 'th' sounds, while

producing "th-words" with [f] in place of voiceless 'th', and [d] or [v] in place of /ð/.

The Puzzle

Phenomenon

ASYNCHRONY BETWEEN

PHONETIC and PHONOLOGICAL

DEVELOPMENT

Caroline Bowen

Citing this article

This page contains an article about

speech development. Cite it as:

Bowen, C. (1998). The puzzle phenomenon:

Asynchrony between phonetic and phonological

development. Retrieved from http://www.speechlanguage-therapy.com/asynchrony.htm on (date).

Phonological development and phonetic

mastery do not synchronise precisely. A

common example of this asynchrony,

referred to by Smith (1973) as the puzzle

phenomenon, is provided by children who

realise /s/ and /z/ as 'th' sounds, while

producing "th-words" with [f] in place of

voiceless 'th', and [d] or [v] in place of

/ð/. The following classic example of

phonetic ability preceding phonological

execution came from a client, Andrew,

aged 4;6. The word on the left in each

case is the target word, and the word on

the right reflects Andrew's production.

some = thumb

thumb = fum

yellow = lello

zoo = thoo

then = den

those = doze

glove = gwub

breathe = bweeve

brother = bwuzzer

globe = blobe

rabbit = brabbit

Lexical selection

Evidence from studies of lexical selection

provides support for the view that children

are "aware" of their phonetic limitations

very early (i.e., during the first 50 words

stage) (Ferguson & Farwell, 1975;

Schwartz & Leonard, 1982). How

conscious the awareness is, of course is

uncertain, but children do seem to reflect

limitations of motor speech control in their

early word choices.

Does this mean that the speech motor

mechanism of young children is in fact

immature? Studies of duration, coarticulation (Kent, 1982; Hawkins, 1984)

and variability (Smith, Sugarman & Long,

1983) in children’s speech have

demonstrated that this is likely to be the

case. Hawkins (1984) reviewed a series of

comparative studies of child and adult

segment and phrase durations, concluding

that children tend to have longer

durations, and hence slower speech rate.

Hawkins also found that children show

greater intrasubject variability of speech

segment and phrase durations than

adults. Smith, Sugarman and Long (1983)

demonstrated that such variability was

due in large part to immaturity of the

neuromotor mechanism for the control of

speech movements.

Co-articulation

Co-articulatory ability, or the normal

capacity to produce an overlap between

speech sounds, caused by an overlapping

in the sequence of gestures which produce

them, has been thought by Kent (1983)

and others, to increase with age. Later

studies of co-articulatory ability (Repp,

1986, Sereno and Liebermann, 1987),

suggest that speech rate and variability

are more relevant predictors than the age

of the child. They showed that the

development of co-articulatory ability

varied widely from child to child, and that

the length of time a sound had been in a

child’s repertoire may be more significant

than chronological age in predicting coarticulatory ability. Sereno and

Liebermann (1987), in a study of children

aged 2;8 to 7;1, found no correlation

between age and co-articulatory ability.

Further evidence that phonetic development is

implicated in the development of phonological

contrasts comes from the frequent observation

that phonological contrasts are realised in the

child’s speech, albeit inaccurately, as they

gradually perfect their phonemic realisations of

target forms.

Children’s progress towards the adult targets of

/s/ and /r/, commonly via interdental and

labialised versions, respectively, are examples

of the "perfecting" process that takes place.

Menn (1983) summed up the complex (and

fascinating) interplay between the levels of

development and learning of phonological and

phonetic processing:

The mismatches between adult model and child

word are the result of the child’s trial and error

attempts; they are shaped by the child’s

articulatory and auditory endowments (and this

to that extent are ‘natural’) and by the child’s

previous success in sound production. All rules

of child phonology are learned in the sense that

the child must discover for herself each

correspondence between the sounds she hears

and what she does with her vocal tract in an

attempt to produce these sounds. (p. 44)

Developmental Phonological Disorders

What are developmental phonological disorders?

Developmental Phonological Disorders are a group of language disorders, whose

cause is unclear, that affect children’s ability to develop easily understood speech

patterns by the time they are four years old. Developmental phonological disorders

can also affect children's ability to learn to read and spell.

Developmental

Phonological Disorders

INFORMATION FOR FAMILIES

Copyright © 1998 Caroline Bowen

Citing this article

This page contains an article about phonological

disorder. Cite it as:

Bowen, C. (1998). Developmental phonological disorders:

Information for families.

Retrieved from http://www.speech-languagetherapy.com/parentinfo.html on (date).

What are developmental

phonological disorders?

Developmental Phonological Disorders (also called

"phonological impairments" or "phonological

disorders") are a group of language disorders that

affect children’s ability to develop easily understood

speech by the time they are four years old, and, in

some cases, their ability to learn to read and spell.

Phonological disorders involve a difficulty in

learning and organising all the sounds needed for

clear speech, reading and spelling.

They are disorders that tend to run in families.

Developmental phonological disorders may occur in

conjunction with other communication disorders such

as stuttering, specific language impairment, or

childhood apraxia of speech.

Synonyms

There is a little note here about the prevalent use of

the confusing and inappropriate term "phonological

processing disorder" and a list of some of the other

names that Developmental Phonological Disorders go

by!

What is involved in learning to

speak clearly?

The emergence in children of a properly organised

speech sound system is called phonological

development. Phonological development involves

three aspects:

the way the sound is stored in the child’s mind;

the way the sound is actually said by the child; and,

the rules or processes that map between the two

above.

Are these three aspects important

in therapy?

They are very important. Phonological therapy

always takes into account these three aspects, and the

fact that phonological development is a gradual

process for all children, whether they have

phonological problems or not. There is a range of

evidence based ("scientific") approaches to

phonological therapy.

Do all children with phonological

disorders need therapy?

No, some children simply need a little extra time to

catch up with their peers.

Most children with phonological disorders need more

time and speech-language pathology intervention

(speech therapy).

Assessment by a speech-language pathologist helps

determine what the particular needs of an individual

child are.

What are the characteristics of

phonological disorders?

Some children with developmental phonological

disorders have other speech and language difficulties

such as immature grammar and syntax, stuttering or

word-retrieval difficulties. However, many of them

just have a 'pure' developmental phonological

disorder, involving:

a problem with speech clarity in the preschool years,

with no subsequent reading and spelling problems, or

a problem with speech clarity in the pre-school years,

and, in the early school years, difficulty learning to

read, and difficulties with reading comprehension, or

speech and reading problems as described above,

plus difficulty with spelling, or

speech and spelling problems (i.e., no reading

difficulties), or

speech clarity problems in the pre-school years, and

difficulties with written expression in primary school.

Can the problems be treated?

Certainly! No matter what combination of difficulties

a child with a developmental phonological disorder

has, appropriate speech-language pathology treatment

is usually successful in eliminating or at the very

least, reducing the problem.

Why are reading and spelling

problematic?

Speech-Language Pathologists are constantly asked

the following two questions:

(1) "Why do some children, who have apparently

overcome their developmental phonological disorder,

in that their speech now sounds quite all right, have

reading and spelling problems?"

(2) "Why do they have difficulty with, or slowness in,

acquiring the pre-literacy skills that are a necessary

foundation for learning to read fluently with

understanding, spell, and produce written work?"

As parents and professionals we are finally beginning

to get some answers to these important questions.

Current research is showing that it is because these

children have poor phonological awareness in

particular, and poor metalinguistic ability generally.

Phonological awareness is the ability to recognise

and manipulate the sounds and syllables used to

compose words. Metalinguistic ability is the capacity

to think about and talk about language.

This is important!

Children with phonological impairments do not

necessarily go on to experience literacy problems, but

children who still have phonological disability in the

form of speech errors (especially those at the severe

end of the scale) when they start school, are very

much at risk for difficulties learning to read and spell.

This is one reason for wanting to treat them early, at

three or four years of age.

The other main reasons for treating children with

phonological disorders early are that it can be

frustrating, socially isolating, detrimental to selfesteem and confidence, and unpleasant generally, to

have speech that is difficult to understand compared

with the majority of children of similar age.

More information

If you have more questions and concerns about

developmental phonological disorders, or you would

like more information about children's speech sound

disorders, including childhood apraxia of speech

(CAS), go to this article. If you would like to read

about language development go to this article, and if

you would like to know more about how speech

develops, go here.

Are there other names for 'developmental phonological disorders'?

Developmental phonological disorders are known by many names including

'phonological disorder' and 'phonological dealay', and 'phonological impairment'.

Synonyms

FOR DEVELOPMENTAL

PHONOLOGICAL DISORDERS

Copyright © 1998 Caroline Bowen

Probably the best known synonym for

developmental phonological disorders

(Bowen, 1998) is 'phonological disability'

found in the early work of Ingram (1976),

and Grunwell (1981a, b). They are also

called phonological impairments.

As well, in the literature they are referred to

as: phonomotor disability (Folkins & Bleile,

1990), syntactic phonological syndrome

(Howell & Dean, 1991), phonological

disorder (Dean, Howell, Hill & Waters, 1990;

Fey, 1992; Kamhi, 1992; Stackhouse,

1993), and expressive phonological

impairment (Bird, Bishop & Freeman, 1995).

Dodd (1995) distinguished three distinct

types of phonological disorder (excluding

articulation disorders): delayed phonological

acquisition, inconsistent deviant disorder,

and consistent deviant disorder. Grunwell

and Russell (1990) also posited at least

three types, related to (1) form: the

inventory and contrastive system, (2)

function: the variability in the realisation of

adult contrasts, and (3) phonotactics (the

latter type discussed in detail in Grunwell &

Yavas, 1988).

There are references in the recent literature

to developmental phonological disorders as

other adjective-adjective-noun labels,

including permutations of the following, with

or without the word "learning", for instance,

developmental phonological learning

disorder (Gibbon & Grunwell, 1990):

functional

articulation

disorder

non-organic

phonologic(al)

disability

(ies)

developmental intelligibility

impairment(s)

child(hood)

phonetic

delay(s)

paediatric

speech

deviations

Misleading names!

Despite the fact that they are mentioned a

lot "phonological processing disorder",

"phonological process disorder" and

"phonological processes disorder" are not

synonyms for developmental phonological

disorder. They are inaccurate and

misleading terms and not proper SpeechLanguage Pathology diagnostic categories.

Somehow they have crept into the

vernacular - particularly in listservs, chat

and newsgroups. As an SLP and Clinical

Phonologist - I wish they would creep out

again!

References

Bird, J., Bishop, D.V.M., & Freeman, N.H.

(1995). Phonological awareness and literacy

development in children with expressive

phonological impairments. Journal of Speech

and Hearing Research, 38, 446-462.

Bowen, C. (1998). Developmental

phonological disorders: A practical guide for

families and teachers. Melbourne: The

Australian Council for Educational Research

Ltd.

Dean, E., Howell, J., Hill, A., & Waters, D.

(1990). Metaphon Resource Pack. Windsor,

Berks: NFER Nelson.

Dodd, B. (1995). Differential diagnosis and

treatment of children with speech disorder.

London: Whurr Publishers.

Fey, M.E. (1992). Clinical forum:

Phonological assessment and treatment.

Articulation and phonology: An introduction.

Language Speech and Hearing Services in

Schools, 23, 224.

Folkins, J., & Beale. K. (1990). Taxonomies

in biology, phonetics, phonology and speech

motor control. Journal of Speech and

Hearing Disorders, 55, 596-612.

Gibbon, F., & Grunwell, P. (1990). Specific

developmental language learning disabilities.

In P. Grunwell (Ed.). Developmental speech

disorders. Edinburgh, Churchill Livingstone.

Grunwell, P. (1981a). The nature of

phonological disability in children. New York:

Academic Press.

Grunwell, P. (1981b). The development of

phonology: A descriptive profile. First

Language, iii, 161-191.

Grunwell, P., & Russell, J. (1990). A

phonological disorder in an English-speaking

child: A case study. Clinical Linguistics and

Phonetics, 4, 29-38.

Grunwell, P., & Yavas, M. (1988).

Phonotactic restrictions in disordered child

phonology: A case study. Clinical Linguistics

and Phonetics 2, 1-16.

Howell, J., & Dean, E. (1991). Treating

phonological disorders in children: Metaphon

- theory to practice. San Diego: Singular

Publishing Group, Inc.

Ingram, D. (1976). Phonological disability in

children. London: Edward Arnold.

Kamhi, A.G. (1992). Clinical forum:

Phonological assessment and treatment. The

need for a broad-based model of

phonological disorders. Language Speech

and Hearing Services in Schools, 23, 261268.

Stackhouse, J. (1993). Phonological disorder

and lexical development: Two case studies.

Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 9, 2,

230-241.

Why do SLPs call the same thing by different names?

Good question!

Phonological processing disorder??!

There are two terms that are not included in the list of synonyms. They are

"phonological processing disorder" and "phonological processes disorder". Despite

their wide usage, these incorrect (and misleading) terms are not synonyms for

developmental phonological disorder. Neither are they names for closely related

speech sound disorders. They are "made up" terms that have somehow crept into

listservs and discussions. Even SLPs sometimes use them!

Synonyms

FOR DEVELOPMENTAL

PHONOLOGICAL DISORDERS

Copyright © 1998 Caroline Bowen

Probably the best known synonym for

developmental phonological disorders

(Bowen, 1998) is 'phonological disability'

found in the early work of Ingram (1976),

and Grunwell (1981a, b). They are also

called phonological impairments.

As well, in the literature they are referred to

as: phonomotor disability (Folkins & Bleile,

1990), syntactic phonological syndrome

(Howell & Dean, 1991), phonological

disorder (Dean, Howell, Hill & Waters, 1990;

Fey, 1992; Kamhi, 1992; Stackhouse,

1993), and expressive phonological

impairment (Bird, Bishop & Freeman, 1995).

Dodd (1995) distinguished three distinct

types of phonological disorder (excluding

articulation disorders): delayed phonological

acquisition, inconsistent deviant disorder,

and consistent deviant disorder. Grunwell

and Russell (1990) also posited at least

three types, related to (1) form: the

inventory and contrastive system, (2)

function: the variability in the realisation of

adult contrasts, and (3) phonotactics (the

latter type discussed in detail in Grunwell &

Yavas, 1988).

There are references in the recent literature

to developmental phonological disorders as

other adjective-adjective-noun labels,

including permutations of the following, with

or without the word "learning", for instance,

developmental phonological learning

disorder (Gibbon & Grunwell, 1990):

functional

articulation

disorder

non-organic

phonologic(al)

disability

(ies)

developmental intelligibility

impairment(s)

child(hood)

phonetic

delay(s)

paediatric

speech

deviations

Misleading names!

Despite the fact that they are mentioned a

lot "phonological processing disorder",

"phonological process disorder" and

"phonological processes disorder" are not

synonyms for developmental phonological

disorder. They are inaccurate and

misleading terms and not proper SpeechLanguage Pathology diagnostic categories.

Somehow they have crept into the

vernacular - particularly in listservs, chat

and newsgroups. As an SLP and Clinical

Phonologist - I wish they would creep out

again!

References

Bird, J., Bishop, D.V.M., & Freeman, N.H.

(1995). Phonological awareness and literacy

development in children with expressive

phonological impairments. Journal of Speech

and Hearing Research, 38, 446-462.

Bowen, C. (1998). Developmental

phonological disorders: A practical guide for

families and teachers. Melbourne: The

Australian Council for Educational Research

Ltd.

Dean, E., Howell, J., Hill, A., & Waters, D.

(1990). Metaphon Resource Pack. Windsor,

Berks: NFER Nelson.

Dodd, B. (1995). Differential diagnosis and

treatment of children with speech disorder.

London: Whurr Publishers.

Fey, M.E. (1992). Clinical forum:

Phonological assessment and treatment.

Articulation and phonology: An introduction.

Language Speech and Hearing Services in

Schools, 23, 224.

Folkins, J., & Beale. K. (1990). Taxonomies

in biology, phonetics, phonology and speech

motor control. Journal of Speech and

Hearing Disorders, 55, 596-612.

Gibbon, F., & Grunwell, P. (1990). Specific

developmental language learning disabilities.

In P. Grunwell (Ed.). Developmental speech

disorders. Edinburgh, Churchill Livingstone.

Grunwell, P. (1981a). The nature of

phonological disability in children. New York:

Academic Press.

Grunwell, P. (1981b). The development of

phonology: A descriptive profile. First

Language, iii, 161-191.

Grunwell, P., & Russell, J. (1990). A

phonological disorder in an English-speaking

child: A case study. Clinical Linguistics and

Phonetics, 4, 29-38.

Grunwell, P., & Yavas, M. (1988).

Phonotactic restrictions in disordered child

phonology: A case study. Clinical Linguistics

and Phonetics 2, 1-16.

Howell, J., & Dean, E. (1991). Treating

phonological disorders in children: Metaphon

- theory to practice. San Diego: Singular

Publishing Group, Inc.

Ingram, D. (1976). Phonological disability in

children. London: Edward Arnold.

Kamhi, A.G. (1992). Clinical forum:

Phonological assessment and treatment. The

need for a broad-based model of

phonological disorders. Language Speech

and Hearing Services in Schools, 23, 261268.

Stackhouse, J. (1993). Phonological disorder

and lexical development: Two case studies.

Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 9, 2,

230-241.

Are developmental phonological disorders something new?

No. In the past, a phonological disorder was termed a 'functional articulation

disorder', and the relationship between it and learning basic school work (like

reading and spelling) was not well recognised. Children were just thought to have

difficulty in articulating the sounds of speech. Traditional articulation therapy was

used to rectify the problem.

Is 'developmental phonological disorder' a 'functional articulation

disorder' under a different name?

'Developmental phonological disorder' is not simply a new name for an old problem.

The term reflects the influence of psycholinguistic theory on the way speechlanguage pathologists now understand phonological disorders. Nowadays, the

traditional diagnostic classification of 'functional articulation disorder' is falling into

disuse.

Children with phonological disability are usually able to use, or can be quickly taught

to use, all the sounds needed for clear speech - thus demonstrating that they do not

have a problem with articulation as such. In other words, we now know that the

problem is not a motor speech disorder. more here

Just to complicate matters, however, some children with developmental phonological

disorders also have difficulties with fine motor control and/or motor planning for

speech.

The difference between an

articulation disorder and a

phonological disorder

Copyright 2002 Caroline

Bowen

Citing this article

This page contains an article about

speech disorders. Cite it as:

Bowen, C. (2002). The difference between an

articulation disorder and a phonological disorder.

Retrieved from www.speech-languagetherapy.com/phonetic_phonemic.htm on (date).

Familiar questions

A question from the parent of a four

year old with difficult-to-understand

speech:

What is the difference between an

articulation disorder and a phonological

disorder? How can you tell the difference?

Are they treated differently?

A question from a colleague:

Although I have been a school-based SLP

for over 20 years I have to say I am

confused about the distinction between

phonetic speech sound disorders, and

phonemic speech sound disorders. In

simple terms, what exactly is the

difference?

Speech

Speech is the spoken medium of

language. Speech has a phonetic level and

a phonological (or phonemic) level.

Phonetic (articulation) level

The phonetic level takes care of the motor

act of producing the vowels and

consonants, so that we have a repertoire

all the sounds we need in order to speak

our language.

Phonological (phonemic) level

The phonological or phonemic level is in

charge of the brainwork that goes into

organising the speech sounds into

patterns of sound contrasts so that we can

make sense when we talk.

Articulation (phonetic) disorder

In essence, an articulation disorder is a

SPEECH disorder that affects the

PHONETIC level. The child has difficulty

saying particular consonants and vowels.

The reason for this may be unknown (e.g.,

children with functional speech

disorders who do NOT have serious

problems with muscle function); or the

reason may be known (e.g., children with

dysarthria who DO have serious problems

with muscle function).

Typical speech development

Speech-Language Pathologists make a

detailed study of all aspects of normal

human communication and its

development in the areas of voice,

speech, language, fluency and

pragmatics. A thorough knowledge and

understanding of what science reveals

about typical speech development is

critical to our understanding of children's

speech sound disorders.

Language

Language has been called the

symbolisation of thought. It is a learned

code, or system of rules that enables us to

communicate ideas and express wants

and needs. Reading, writing, gesturing

and speaking are all forms of language.

Language falls into two main divisions:

receptive language (understanding what is

said, written or signed); and, expressive

language (speaking, writing or signing).

Phonological disorder

A phonological disorder is a LANGUAGE

disorder that affects the PHONOLOGICAL

(phonemic) level. The child has difficulty

organising their speech sounds into a

system of sound contrasts (phonemic

contrasts).

What is the difference

between an articulation

disorder and a

phonological disorder?

In an articulation disorder the child's

difficulty is at a phonetic level. That is,

they have trouble making the individual

speech sounds.

In a phonological disorder the child's

difficulty is at a phonemic level (in the

mind). This "phonemic level" is sometimes

referred to as "the linguistic level" or "a

cognitive level".

Co-occurrence

An articulation disorder and a phonological

disorder can co-occur. That is, the same

child can have BOTH.

Assessment and diagnosis

Because of their knowledge-base, SpeechLanguage Pathologists (SLPs) are able to

distinguish between the many speech and

language disorders they have to assess

(or "differentially diagnose") in the course

of their work.

The assessment process typically involve

screening the child's communication skills

in a general way, and then forming an

hypothesis about the nature of any

apparent difficulties.

If speech clarity is a problem the SLP will

examine both the PHONETIC and the

PHONOLOGICAL aspects of the child's

speech. The tests chosen will depend on

the child's presentation and the theoretical

beliefs of the clinician.

Use of terminology

Some SLPs use the term "articulation

disorder" very loosely, especially when

they are explaining these complex ideas

to people who do not have a background

in linguistics or speech pathology. Indeed,

they may refer to a "phonological

disorder" as an "articulation disorder".

It can often be quite helpful for parents to

ask their SLP what they mean by the

particular terms they use.

"Functional"?

The term "functional" speech disorder' is

usually equated with the concept of

"cause unknown" and these disorders are

often referred to as speech disorders of

unknown origin.

Although we cannot "prove" or

"demonstrate" what has "caused" a

speech sound disorder in a particular

child, we can often form justifiable

hypotheses regarding the likely cause,

given a child's history (Flipsen, 2002).

Factors such as family history, frequent

otitis media, developmental apraxia of

speech, and psychosocial factors

(Shriberg, 1993) may be considered.

Developmental?

The word "developmental" in

"developmental phonological disorders",

"developmental dysarthria", and

"developmental apraxia of speech" (the

preferred term is "childhood apraxia of

speech") simply denotes that the

disorders occur in children. The word

"developmental" is not appended to

functional speech disorders, which occur

in both children and adults.

Intervention

There is information about the treatment

of children's speech sound disorders here.

Discussion

The phonological therapy discussion

group provides communication disorders

professionals with an opportunity to ask

and answer questions and explore

theoretical and research issues related to

young children's speech sound disorders

in general, and developmental

phonological disorders, articulation

disorders, and developmental apraxia of

speech in particular. The emphasis is on

theoretically sound, evidence-based

clinical assessment and intervention.

What is traditional articulation therapy?

There is no single definition of traditional articulation therapy. It is a term that is

applied to a number of therapy approaches that focus on the motor aspects of

speech production, with or without auditory discrimination training.

In essence, traditional articulation therapy involves behavioural techniques, focused

on teaching children new sounds in place of error-sounds or omitted sounds, one at a

time, and then gradually introducing them (new sounds that is) into longer and

longer utterances, and eventually into normal conversational speech.

Traditional Articulation

Therapy

Copyright © 1999 Caroline

Bowen

This page contains an article about

articulation therapy. Cite it as:

Bowen, C. (1999). Traditional articulation therapy.

Retrieved from http://www.speech-languagetherapy.com/TraditionalTherapy.htm on (date).

What constitutes the so-called

"traditional" approach to "articulation

therapy"? There is no single definition, for

indeed a number of beliefs and practices

may be involved, and the term clearly

means different things to different people,

depending on what they thought was

generally done.

Some of the procedures which have

characterised speech-language pathology

assessment and intervention for functional

speech disorders (articulation disorders),

and which may be considered by many

speech-language pathologists to embrace

"traditional" approaches, were described

by Powers (1971). She maintained that

the "stimulus methods" developed and

described by Travis (1931), had remained

the core of the majority of treatment

methodologies used by speech-language

pathologists.

Powers began her therapy with auditory

discrimination training. A sound was

identified, named, discriminated from

other speech sounds, and then

discriminated in contexts of increasing

complexity.

Permutations of the traditional approach,

always putting discrimination of sounds

produced by others first, are to be found

in Berry and Eisenson (1956), Carrell

(1968), Garrett (1973), Sloane and

Macaulay (1968) and and of course, Van

Riper (1978), who wrote:

"The hallmark of traditional therapy lies in

its sequence

of activities for: (1) identifying the

standard sound,

(2) discriminating it from its error through

scanning

and comparing, (3) varying and correcting

the various

productions until it is produced correctly,

and finally,

(4) strengthening and stabilizing it in all

contexts and

speaking situations." Van Riper, 1978 p.

179

Therapy resources designed for the

administration of traditional approaches to

speech therapy for children's speech

sound disorders continue to be published,

some incorporating aspects of other

programs and methodologies, and some

with evidence of internal development.

Adopting the role of teacher, the therapist

guides the child through a series of

carefully sequenced and graded steps,

usually one phoneme at a time. The

procedure starts with ear training, and

goes on through increasingly complex

production contexts. Finally the phoneme

is used in spontaneous conversational

speech, and the emphasis moves to selfmonitoring.

The child takes a passive learning role,

with active exploration and processing of

the sound system not specifically

encouraged. The approach, rather than

being communication centred, is "therapy"

centred, with the child learning what the

therapist sets out to teach.

Following the example of the medical

profession, published evidence of the

success of traditional approaches has

been mainly in the form of case

illustrations and clinical descriptions (for

example, Powers, 1971; Travis, 1931;

Van Riper & Irwin, 1959).

Is traditional therapy still an acceptable form of treatment?

Traditional therapy techniques, using the format outlined above, have withstood the

test of time, and can still be very suitable for children with functional speech

disorders.

What is a functional speech disorder?

A functional speech disorder is a difficulty learning to make specific speech

sounds. The index page for a series of articles about functional speech disorders is

here.

Children with just a few speech-sound difficulties such as lisping (saying 'th' in place

of 's' and 'z'), or problems saying 'r', 'l' or 'th' are usually described as having

functional speech disorders. But, you guessed it! There are synonyms for this too.

Functional speech disorders are often referred to as 'mild articulation disorders' or

'functional articulation disorders'. Examples include:

The

The

The

The

The

The

word

word

word

word

word

word

super pronounced as thooper.

zebra pronounced as thebra.

rivers pronounced as wivvers.

leave pronounced as weave.

thing pronounced as fing.

those pronounced as vose.

NOTE:

Some of these sound changes are acceptable in a number of English dialects.

FUNCTIONAL SPEECH

DISORDERS

What are

they?

Copyright 2004 Caroline

Bowen

Functional Speech Disorders INDEX

Difficulty with one, or just a

few sounds

Functional speech disorder is one of

several speech sound disorders that can

occur in children. A child with a functional

speech disorder has difficulty learning to

make a specific speech sound (e.g., /r/),

or a few specific speech sounds, which

may include some or all of these: /s/, /z/,

/r/, /l/ and 'th'.

Synonyms

Functional speech disorders are

sometimes referred to as "articulation

disorders", "functional articulation

disorders" or "articulation problems".

Functional speech disorders are not the

same thing as developmental phonological

disorders, developmental apraxia of

speech, or developmental dysarthria. The

similarities and differences between these

disorders are discussed in this article

about speech sound disorders.

The precise cause is unknown

By definition, the precise cause (or

causes) of functional speech disorders is

(or are) usually unknown. Even so, we do

know that structural (anatomical),

linguistic and environmental factors,

persistent ear infections associated with

intermittent hearing problems, and other

significant interruptions to a young child's

health and well-being, can impact

negatively on speech acquisition.

Assessment

All speech-language pathology

intervention is based upon individual,

ongoing assessment of a client's

communication skills. The therapist first

"screens" all areas of communicative

function, including voices, speech,

language, fluency and pragmatics, and

then does an in-depth assessment of

particular areas that may be problematic.

The assessment may include clinical

observations and standardised and nonstandardised tests.

Diagnosis

Informed assessment provides the basis

for diagnosis. The speech-language

pathologist is able to tell the young

client's carers, or the older client, what

the problem is, discuss the extent and

severity of the problem, and explore

treatment options.

Therapy (Treatment) Planning

Ideally, the Speech-Language Pathologist

will be able to propose a treatment plan

that he or she believes is both evidencebased (or theoretically sound) and optimal

for a particular client.

For example, a child of 5 who substitutes

/w/ for /r/ ("wabbit" for "rabbit") may be

offered 10 once-weekly therapy

appointments augmented by daily

homework (practice), then a break of

about four weeks, with a plan to review

progress at that time.

Parents would be given an expectation

that, with appropriate intervention and

good co-operation between clinician,

family and child, it would be reasonable to

expect the problem to resolve within 14

weeks or so. It would be explained that

some children require more or less

therapy than others.

Prognosis

A prognosis is a prediction about the likely

outcome of therapy. In general the

prognosis for the successful treatment of

functional speech disorders in children is

good.

However, the therapist may not feel ready

to talk about prognosis immediately after

assessment and diagnosis, preferring to

wait until the child has had a few

treatment sessions and until he or she and

his or her family is into a routine of doing

the necessary supervised home practice.

Prognosis may not be as positive if the

child does not comply with homework, or

does not receive appropriate

encouragement at home. There is more

information about homework below.

Therapy (Treatment) for

children

For many years Speech-Language

Pathologists have been remarkably

successful in treating individuals with

functional speech disorders using

evidence-based (scientific) traditional

and innovative approaches. There is an

intersting article on the ASHA web site

about former White House press secretary

Ari Fleischer who was successfully

treated for a functional speech disorder

when he was a child. Looking back on this

positive experience, Fleischer is quoted as

saying:

"I hope I can inspire children who have

lisps and others with speech disorders to

realize that it can be a phase in your life

that you deal with and go through, and it’s

over and you can still have a wonderful

future ahead.

And I also would say to all the speechlanguage pathologists and other health

care workers that you never know what

impact you are having on the children you

are treating today. In first grade, Dr.

Shulman made a difference in my life that

I’m sure he never anticipated at the time."

Therapy (Treatment) for adults

If they are not successfully treated in the

early years, functional speech disorders

can persist into adulthood, often causing

considerable distress. These adults may

have difficulty pronouncing just one or

two sounds, like /s/ and/z/, or just /r/, or

just /l/. On this page adults talk about

their experience of lisping.

With speech-language pathology

intervention and a monitored (by the SLP)

practice schedule, motivated adults often

overcome these disorders, achieving

"standard" speech sound production of

any of the sounds that were previously in

error.

Homework for children

There is research evidence to show that

supervised, appropriate homework

expedites therapy gains. "Supervised" in

this context means that homework tasks

have been devised by the clinician on a

case-by-case basis, in response to the

progress (or sometimes lack of progress)

made by the child.

Homework typically "builds" on previous

therapy sessions and previous homework.

Usually, the homework for week 1 is no

longer necessary in week 2, and so forth.

Because every child is different, progress

varies for each child. That is why the

therapist, in ideal circumstances, does not

want to hand out an intervention plan for

non-SLPs to administer without

supervision.

Unsupervised, or minimally

supervised home programs

Of course, "ideal" management is not

always possible, and the only intervention

option for some clients is a well-explained

home program, administered by parents

or significant others. With such home

programs it is highly desirable for the SLP

to review progress and provide ongoing