South Carolina's former Attorney General, Charles Molony Condon

Pregnant Women and Drug Use

Charles Condon and South Carolina’s Policy of Punishment Not Treatment

National Advocates for Pregnant Women

1

South Carolina’s former Attorney General, Charles Molony Condon, and frequent

Republican candidate for statewide office, has made a career based on extremist positions. His most extreme position—edging out his advocacy of an electric sofa to expedite executions and his effort to keep the confederate flag flying above the state capitol—is his commitment to the prosecution and punishment of poor pregnant women.

Although he has repeatedly claimed that this was a policy of “last resort” that “was not punitive…not designed to put people in jail,” 2 but designed to promote treatment of pregnant women with drug problems, the record makes clear that punishment was and continues to be the first and only response for many South Carolina women seeking medical help for themselves and their children.

As State Solicitor, Mr. Condon, in cooperation with the Medical University of South

Carolina—and later other hospitals across the state—set out to illegally search, then arrest and jail pregnant women with drug problems. He claimed his basis for doing so was to stem the tide of the so-called “Crack Baby” epidemic.

3

The administration of this policy was problematic from the start. The medical community has found no scientific basis for the term “Crack Baby,” or for the many harms attributed to this drug in particular. A letter written by the 30 leading researchers—deploring the use of exactly the kind of stigmatizing and scientifically false terms frequently used by Mr. Condon— concluded: “Throughout almost 20 years of research, none of us has identified a recognizable condition, syndrome or disorder that should be termed “crack baby.” 4

In 1989, as Mr. Condon was initiating his search and arrest protocol, not a single drug treatment program in the state had treatment for pregnant cocaine dependent women—the targets of his program.

5

Nearly all of the women arrested under his policy were African-

American even though drug use crosses all race and class lines. Moreover, although Mr.

Condon claimed the program was needed to protect children uniquely harmed by prenatal exposure to cocaine, and even though he described his program as being “out there protecting the children, ” 6

no program was created to track or treat the children. This fact is consistent with a program that at its heart was and continues to be solely about punishing pregnant women. It is perhaps then no wonder that the United States Supreme

Court found that the policy Mr. Condon helped to initiate, violates the 4 th

Amendment’s prohibition on unreasonable searches and seizures.

7

Mr. Condon continues to claim that

“this whole program was never about maternal prosecution. It's about fetal protection,” 8

1

but the US Supreme court found the exact opposite, that “the immediate objective of the searches [drug tests] was to generate evidence for law enforcement purposes.” 9

Despite these findings Mr. Condon has not only vigorously defended and promoted the arrest of pregnant women, he has been dishonest in his presentation of this uniquely punitive program. Mr. Condon, in his own writing, characterized the program as an

“amnesty program” 10

that offered protection from punishment for anyone willing to get treatment. As he explained, “Either seek drug treatment or face arrest and jail time,” 11

Indeed, he went so far as to say that under his program: “The only way you can go to jail is to break in. You have to refuse to accept amnesty and refuse to accept drug treatment.” 12

Lori Griffin did not break in to jail.

In 1989, Ms. Griffin, an African-American woman, was arrested for distribution of drugs to a minor while she was eight months pregnant. Prior to her arrest, she made multiple visits to the Medical University of South Carolina for prenatal care. During the first visit, she gave blood and urine samples, but as she would later testify under oath, she was not offered or referred to any drug treatment prior to her arrest.

13

Her medical records confirm that despite knowledge of her problem, health providers never counseled, referred, or provided treatment to her for this treatable condition. Mr. Condon nevertheless claimed in a statement before a federal oversight committee that “In fact, we don’t put pregnant addicts in jail.” 14 Yet, in fact, that is exactly what Mr. Condon’s office had done to Ms. Griffin, not only jailing her but also placing her in handcuffs and shackles, including “a chain that went around my belly.” 15

Mr. Condon’s amnesty resulted in a chained and imprisoned pregnant woman who had gone regularly to seek health care. The shackles and handcuffs remained on while Ms. Griffin was giving birth the following month. Mr. Condon nevertheless insists that his program “treats addicts as patients rather than as criminals.” 16

Saundra Whitlock did not break into jail.

Saundra Whitlock, an African-American woman, was treated as a criminal rather than as a patient. In fact, she was arrested because of her pregnancy and addiction before she ever got treatment. In 1989, Ms. Whitlock and her newborn baby tested positive for cocaine. In a sworn statement, Ms. Whitlock says that she acknowledged her addiction and asked for help, but was arrested instead and was held in jail—as an accused criminal not a patient—for three months.

17

Sandra Powell did not break into jail.

Sandra Powell, an African-American woman, was also arrested in 1989, at MUSC. Ms.

Powell had been receiving prenatal care at MUSC without ever being offered drug treatment. She would later testify under oath that she would have accepted drug treatment had it been offered.

18

In fact, Ms. Powell’s medical records indicate that while the hospital was aware of her cocaine use during her pregnancy

19

there was no offer of

2

treatment prior to—or on the day of—the delivery. Medical records do indicate, however, that on the day of the delivery, October 13 th

, the hospital staff would notify the police and coordinate her in hospital arrest at the time of her discharge.

20 Ms. Powell was arrested just hours after giving birth, while she was still bleeding and in pain.

Ellen Knight did not break into jail.

Less than one month after Ms. Whitlock, another African-American woman, Ellen

Knight, was arrested under similar circumstances. Ms. Knight, who had been receiving prenatal care at MUSC, was arrested after her newborn son tested positive for cocaine.

Ms. Knight was never offered any substance abuse treatment.

21

After the delivery, she was led to believe that she was being released from the hospital. Based on this belief she called her older sons to come pick her up and bring her some clothes.

22 Upon her sons’ arrival, Ms. Knight was arrested. Police wheeled her out of the hospital in front of her sons, in handcuffs, while she was still bleeding and wearing only a hospital gown.

23

Ms.

Knight later sought out drug treatment on her own. She contacted Charleston County

Substance Abuse, but it turns out “they didn’t have a program set up in November of ’89 for this type of thing. I had to wait until January.”

24

Given these facts it is difficult to believe Mr. Condon’s repeated claims to the press, public, and congressional leaders that the only women arrested were those who refused treatment. Mr. Condon likes to characterize his policy as “a program that used not only a carrot, but a real and very firm stick,” 25

but for these women—all of whom reached for the carrot—there was only Mr. Condon’s stick.

In a federal civil rights law suit brought by Ellen Knight, Sandra Powell, Lori Griffin and other MUSC patients against Mr. Condon and the hospital, Mr. Condon’s own attorney,

Robert Hood, admitted that “. . . when the Policy was first initiated, a positive test was immediately reported and the patient was arrested.” 26

In other words–neither treatment nor amnesty played any role whatsoever in the policy as originally conceived of and implemented by Mr. Condon. When the Supreme Court handed down its decision, the

Court’s own recitation of the facts noted that “when the policy was in its initial stages, a positive test was immediately reported to the police, who then promptly arrested the patient.” 27

Despite his own attorney’s admission and the findings of US Supreme Court, Mr.

Condon continues to insist that the only women ever arrested under the policy are those who “choose not to avail themselves of the help.” 28

Moreover, Mr. Condon’s claim that if women get help “there is no arrest, no prosecution, no record of arrest” 29

is also manifestly untrue.

The lead plaintiff in the US Supreme Court case, Crystal Ferguson, provides a good example of Mr. Condon’s mythmaking. Ms. Ferguson gave birth to her baby in August of 1991, nearly two years after the policy’s inception. Ms. Ferguson had tested positive for cocaine in June of 1991. The hospital told her she must enter the hospital’s inpatient treatment program or face arrest. This “program” was part of the hospital’s in-paitnet

3

psychiatric ward. When the policy was first initiated it refused to take pregnant women.

Now, in 1991, it accepted pregnant women, apparently for at least as long as Medicaid would reimburse the hospital, but had no specialized treatment for women. Ms. Ferguson, who consistently indicated her interest in—and willingness to go to—treatment, had two older children at home who needed her care. She refused to enter the inpatient program and abandon her two sons. She asked for a referral to an outpatient program which she readily agreed to attend.

30

Only after she had delivered, was Ms. Ferguson given information about an outpatient treatment—even as a warrant was being issued for her arrest, because of her refusal to abandon her existing children and enter the particular inpatient program arbitrarily selected for her.

31

Once Ms. Ferguson had been given information about the outpatient program, she herself secured an appointment for evaluation and treatment. This appointment was scheduled to begin the same day she was arrested. In fact, she voluntarily went to the police station to address the warrant an hour before her first treatment appointment. The police arrested her, preventing her from making it to the very treatment Mr. Condon claims was the real goal of the policy.

32

South Carolina’s policy of arresting—rather than treating—pregnant women was not limited to Charleston. There are women from across the state whose cases refute Mr.

Condon’s claim that treatment not arrest is the purpose of his policies.

In 1992, Cornelia Whitner, of Pickens County, was an addict in need of treatment. Mr.

Condon would have us believe that under his policy, as a pregnant addict, Ms. Whitner lucked out by finding herself in a state that would give her the help that she so desperately needed. Not only would Ms. Whitner have taken treatment had it been offered to her, she practically begged for it. In response to questions about her drug history, she told Judge Frank Eppes, “I need some help, your honor.” 33

During that same court appearance, Ms. Whitner’s attorney, Cheryl Aaron, told the court, “She [Ms.

Whitner] indicates that she has not used drugs since before the child was born in

February, but she believes that she needs some in-patient help to remain that way.”

Judge Eppes disagreed, stating, “ “ I think I’ll just let her go to jail.” 34

Surely, at that point, Mr. Condon stepped in and petitioned Judge Eppes to cooperate with his groundbreaking policy, right?

Wrong.

When Ms. Whitner contested the criminalization of her pregnancy and her disease, Mr.

Condon, now acting as the state’s Attorney General, fought her all the way to the State

Supreme Court. Even as he fought to keep Ms. Whitner, a woman who had pleaded for treatment, in prison; Mr. Condon continued to portray his policy as one of amnesty with statements such as: “We offered immunity from prosecution, free medical services for the mothers and their babies, and free access to a drug rehabilitation program.” 35

That Mr.

Condon would make such an assertion, in writing—as Ms. Whitner, a woman whose case directly contradicts that statement was being prosecuted—speaks to his dishonest representation of the program. In fact, according to Louise Haynes, former Director of

Offices of Women’s Services at the then South Carolina Commission on Alcohol and

4

Drug Abuse, the treatment options at the time of these women’s arrests were “inadequate to meet the needs of the women referred through the interagency policy.” 36

In spite of Mr. Condon’s misrepresentations, he succeeded in ensuring that a woman who gave birth to a healthy baby would spend 8 years in jail at taxpayers’ expense. The Court found in favor of the State, declaring that viable fetuses are “persons,” and as a result, the state’s criminal child endangerment statute applied to a pregnant woman who used an illicit drug or engaged in any other behavior that might endanger the fetus.

37

For Mr. Condon, it was a victory—but for the women and children of the state it was a disaster. Following the Whitner decision, infant mortality began to increase for the first time in nearly a decade.

38

South Carolina has one of the highest infant mortality rates in the nation, 39 African-American babies in the state are more than twice as likely to die during the first year of life as white babies are,

40

and significantly fewer African-

American Women receive adequate prenatal care when compared to pregnant white women.

41 Participation by both African-American men and women in drug treatment has decreased considerably.

42

In 1998, instead of admitting that there never was any treatment offer attached to the arrests in the state, Mr. Condon created a protocol, bearing Ms. Whitner’s name. It details procedures for identifying and arresting other pregnant drug using women who sought health care. The protocol, among other things requires hospitals to set up joint committees to review cases in which pregnant women test positive for certain illegal drugs. These committees are supposed to consist of members of the Hospital Staffs,

Department of Social Services and the Solicitor’s Office. The protocol also purports— like his earlier MUSC plan—to offer the possibility of treatment first. The last line of

Condon’s plan concluded:

It is essential that we tap into this existing partnership [between the department of

Social Services and Department of Alcohol and other Drug Abuse Services] and other existing programs to provide full service treatment before embarking upon or seeking criminal prosecutions.” 43

Mr. Condon however adopted this so-called “amnesty” program even as he admitted that the treatment women needed simply did not exist in the state. As he explains in his own words:

Though the Department of Alcohol and other Drug Abuse Services authorities provide some state and federally mandated prevention, intervention and treatment services, a wide array of treatment serves are desperately needed in every community in the state.” 44

With that statement, Mr. Condon admitted that his policy had advanced no further from where it was in 1989, when pregnant women and new delivered mothers were taken out of MUSC—some still bleeding—in chains and shackles. A 1998 review of all types of drug treatment in the state confirmed Mr. Condon’s candid assessment of the

5

unavailability of treatment. The report concluded that treatment for South Carolina’s

“women, and pregnant women in particular

, remain underserved.” 45

While Mr. Condon continued to portray his program as one that emphasized treatment

46 still other women in desperate need of compassion and help were arrested rather than offered appropriate treatment. In 1998, Nikki S., of Horry County 47 , was arrested after she suffered a stillbirth. Ms. S. had apparently attempted suicide on her 21 st

birthday.

She was severely depressed and used whatever was available to her including Tylenol, beer and cocaine to try to end her own life. She suffered seizures and was taken to the hospital. An emergency c-section was performed but the fetus did not survive.

48

Department of Social Services records indicate that a member of the Conway Hospital staff notified the police about Ms. S. case three days before she was given even a passing referral to treatment. By then it was too late, as the wheels of punishment were in motion—the police were already procuring a warrant for her arrest. Before she was ever interviewed by a psychiatrist she was being formally interrogated by a police officer.

49

Despite a practice of arresting pregnant women with drug problems without any connection to treatment, Mr. Condon continued to bang the drum for his state’s policy.

During a 2001 television appearance, Mr. Condon described prosecuting pregnant women as a “last resort.” 50

Mr. Condon insisted that “the criminal prosecution is really only used to coerce them, much like the drug courts, into free drug treatment.” 51

In 2002, Bertha Sims was arrested for giving birth to a baby who tested positive for drug residue. Ms. Sims was prepared to accept treatment, but none was ever offered. In fact,

Ms Sims’ attorney wrote—in a sworn statement—that the Solicitor did not “extend any offer of treatment as an alternative to incarceration to Ms. Sims, either directly or through me as her attorney.” 52

As Ms. Sims remained incarcerated, the Solicitor still did not

“provide any information about any ‘amnesty program.’” 53

Ms. Sims’ attorney not the solicitor’s office and not the hospital engaged in extensive efforts to find a treatment program that would take her. One of the few programs in the state that could provide her with treatment originally refused to take her because she could not bring her infant with her. While imprisoned on the criminal charge, Ms. Sims’ child was put in foster care.

Through aggressive advocacy, however, her attorney was able to get her into the program. When she completed that treatment, the charges against her were finally dropped. The Solicitor’s office then, in effect, took credit for the treatment it had obstructed through the immediate arrest and imprisonment of Ms. Sims, claiming that the charges were dropped because “Ms. Sims successfully completed the attorney general amnesty program.” 54

Of course, there is no amnesty program. There never was. Mr. Condon’s statewide program has no legal authority. It is not the result of legislation nor is it even a regulation. The state legislature in 1998 reviewed the protocol and refused to endorse it, but did emphasize a need for adequate treatment options for pregnant women.

55 Requests to various hospitals and state solicitor’s offices for their local plans to implement the protocol have found that committees do not exist and that hospitals have protocols for

6

collecting evidence against the women but not for referring them to treatment.

56

The only part of the protocol that is operational is the arrest portion.

Rather than a tool for punishing those women who will not get help for themselves, Mr.

Condon’s policy has been a tool for punishing women who have actually stopped their drug use and taken responsibility for their children. In 1992, Malissa Crawley, of

Anderson County, gave birth to a baby who tested positive for cocaine. She was charged with unlawful neglect of a child for being pregnant and having a drug problem. Ms.

Crawley pleaded guilty to child endangerment and was given a five-year suspended sentence and probation. In 1994, however Ms. Crawley was being assaulted by her boyfriend. She called the police. They did not as she had hoped protect her and simply arrest her batterer. Instead the police arrested both she and her boyfriendWithout advice of counsel, Ms. Crawley—who between arrests had conquered her addiction—pleaded guilty to the domestic dispute. While that crime carried only a possible 30-day sentence, the guilty plea reinstated the five-year sentence she had received for her prior drug problem. Therefore, Ms. Crawley—off drugs, working and caring for her children—was sent to prison to serve out her five-year sentence for being pregnant while having a drug problem. Mr. Condon could only say “this case does not follow the guidelines of the program.” 57

Deborah Frank, a Boston Medical Center pediatrician, notes: “Certainly one cannot claim you’re helping the children by incarcerating the mother.” 58

But, Mr.

Condon, who claims to treat mothers and protect children, said of the incarceration of drug-free mother of three Malissa Crawley, “My heart does not bleed for her.”

59

Perhaps the saddest case of all the women arrested under the state’s punitive policies is

Regina McKnight. Ms. McKnight, a low income African-American woman with a drug problem, suffered a stillbirth at Conway hospital in Horry County, in 1999. Based on the precedent set in the Whitner case—that in South Carolina fetuses are “persons” under the child abuse statutes—Mr. Condon’s policy reached a new level. Like the women before her, Ms. McKnight was not offered treatment for her substance abuse problem prior to the hospital contacting law enforcement officials. Hospital records document that Child

Protective Services and the Solicitor’s office were contacted without any offer of treatment. Unlike the other women, Ms. McKnight was not simply charged with a child endangering or a distribution charge; Ms. McKnight was charged with “depraved heart” murder for death by child abuse. She was convicted by a jury in fifteen minutes, and sentenced to twelve years in prison. No one in the case thought she had any intent of losing the pregnancy, and national experts and organizations that reviewed the record concluded that the stillbirth was not caused by her drug use.

60

Ms. McKnight currently resides in Leath Correctional institution, a level three facility, which means it is one of the state’s “high security institutions designed primarily to house violent offenders.” 61

Ms. McKnight is not scheduled to be released until August 29 th , 2010.

Mr. Condon’s Legacy

In Mr. Condon’s years of elected office there is no evidence that he used his positions of authority and influence to advocate for additional drug treatment funding—instead he claimed it was freely available when he knew it was not. South Carolina spends fewer

7

state dollars on drug treatment than any other state in the country.

62

In 2000, the state was only able to treat approximately 52,000 of the 310,000 South Carolinians identified as having substance abuse problems.

63 Decades of research have established that a variety of treatment methods are successful for treating people who are addicted to alcohol and other drugs. The most recent national surveys have also confirmed the effectiveness of treatment programs.

64 According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the cost of effective treatment ranges from $1,800 to $6,800 per year while the national average cost of incarceration is over three times as much—20,805 per year.

65

If McKnight serves her full sentence—the state will have spent over $150,000 to imprison her, a far greater cost that providing her with treatment and other social welfare services she might have needed.

The South Carolina Department of Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse Services

(“DAODAS,”) which was created as a cabinet-level department in 1993, 66 is currently facing severe budget cuts; DAODAS and its local provider network have received the largest proportional state funding cut of any agency, amounting to a loss of 50% of funding or $5.5 million since May 2001.

67 This is so despite the evidence that every dollar spent on treatment of addiction saves $7.46 dollars per taxpayer each year by decreasing hospitalization, incarceration, crime, and other public costs.

68

To address these cuts, the agency has had to streamline its service delivery programs, reduce incidental costs such as out-of-state travel and regionalized trainings, and lay off at least 15 employees. In addition, to compensate for the loss of state funds, it increased its FY2003 billing to the Medicaid program for clients enrolled in that program for the fifth consecutive time. The department now relies on the federal Substance Abuse

Prevention and Treatment Block Grant along with Medicaid billing to cover the bulk of its operating costs.

69

To this day South Carolina does not have a single family treatment program – in or out patient – that would allow a woman to obtain appropriate treatment with all of her family members. Moreover, new arrests are occurring and Solicitor Trey Gowdy seems to have stepped into Mr. Condon’s footsteps arresting pregnant women and new mothers and urging area hospitals to turn in pregnant patients rather than working to increase desperately needed treatment services.

70

Finally, far from being limited to women who use drugs, Mr. Condon’s legacy extends to all pregnant women who risk harm to their fetuses and who suffer stillbirths. As the Chief

Solicitor for Horry County declared: "Even if a legal substance is used, if we can determine you are medically responsible for a child's demise, we will file charges."

71

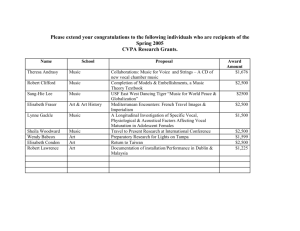

1 NAPW thanks Adam Posner, NAPW 04 Summer Intern for his extensive research and writing contributions to this report.

2 Charles Molony Condon, Clinton’s Cocaine Babies: Why Won’t the Administration Let Us Save Our

Children , Policy Review (Spring 1995), available at http://www.policyreview.org/spring95/condth.html

8

3 Id.

4 Available at http://www.jointogether.org/sa/files/pdf/sciencenotstigma.pdf

5 cite Haynes declaration, some documentation of the fact that MUSC itself turned pregnant women away from its in patient program in it psychiatric unit.

6 Burden of Proof (CNN television broadcast, Mar. 22, 2001), available at http://www.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0103/22/bp.00.html

7 Ferguson v. Charleston, 532 U.S. (2001) (No. 99-936). Please also cite the NIH finding and the Office of

Civil Rights letter – both should be cited in our cross motion for summary judgment.

8 Burden of Proof (CNN television broadcast, Mar. 22, 2001), available at http://www.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0103/22/bp.00.html

9 Ferguson v. Charleston, 532 U.S. 15 (March 21, 2001).

10 Charles Molony Condon, Clinton’s Cocaine Babies: Why Won’t the Administration Let Us Save Our

Children , Policy Review (Spring 1995), available at http://www.policyreview.org/spring95/condth.html

.

It should be noted that the while amnesty is defined as a general pardon granted by a government, especially for political offenses, Mr.

Condon has taken the opposite approach in these cases, creating a definition of amnesty as a criminalization undertaken by government, especially for political purposes.

11 Id.

12 Associated Press, Appeals court ruling victory for cocaine test, T HE P OST AND C OURIER (C HARLESTON

S.C.), July 14, 1999, at B6.

13 Ferguson v. Charleston, 532 U.S. (2001) Griffin testimony Tr. 5:2-17 (JA).

14 Charles M. Condon, Attorney General of South Carolina, Before the House Committee on Government

Reform and Oversight Subcommittee on National Security, International Affairs and Criminal Justice

Federal Information Systems Corporation, F ED .

N EWS S ERV ., July 23, 1998, at 1.

15 Ferguson v. Charleston, 532.

U.S. (2001) Griffin testimony Tr. 9:14-17 (JA).

16 Charles M. Condon, Attorney General of South Carolina, Before the House Committee on Government

Reform and Oversight Subcommittee on National Security, International Affairs and Criminal Justice

Federal Information Systems Corporation, F ED .

N EWS S ERV ., July 23, 1998, at 1.

17 Ferguson v. Charleston, 532 U.S. (2001) Statement of Saundra Whitlock, C/A No. 2:93-2624-2

18 Ferguson v. Charleston, 532 U.S. (2001) Powell testimony Tr. 179:25-180:3

19 Id at A2436

20 Id at A2441

21 Ferguson v. Charleston, 532 U.S. (2001) Knight testimony Tr. 121:7-10, 121:25-122:3 (JA).

22 Id at 124:20-24 (JA).

23 Id at 125:13-126:22 (JA).

24 Id at 137:23-138:1

25 Charles Molony Condon, Clinton’s Cocaine Babies: Why Won’t the Administration Let Us Save Our

Children , Policy Review (Spring 1995), available at http://www.policyreview.org/spring95/condth.html

26 Ferguson v. Charleston, 532 U.S. (2001) (No. 99-936).

27 Ferguson v. Charleston, 532 U.S. 4 (March 21, 2001).

28 The Edge: with Paula Zahn (FoxNews television broadcast, Jun. 25, 2001).

29 Id.

30 Ferguson v. Charleston, 532 U.S. (2001) Ferguson testimony Tr. 183:7-23 (JA).

31 Id at PX 274

32 Ferguson v. Charleston, 532 U.S. (2001) Ferguson testimony Tr. 188:24-189:12 (JA).

33 Whitner v. South Carolina, 92-GS-39-670, Tr. 51:8 (JA).

34 Id at 55:10-13 (JA).

35 Charles Molony Condon, Editorial, Bureaucrats Stopped Crack-Baby Prevention Program , T HE

G REENVILLE N EWS , May 28, 1995, at 3.

36 Ferguson v. Charleston, 532 U.S. (2001), Declaration of Louise Haynes, Oct 5, 1993.

37

Whitner v. State, 492 S.E.2d 777 (S.C. 1997), cert. denied, 118 S. Ct. 1857 (1998).

38

39 Depending on the source, South Carolina ranks between the worst and the third worse state in the country for infant mortality and other perinatal health indicators. According to the Children’s Defense fund, South

Carolina ranks 50th among states in infant mortality. Children’s Defense Fund, Children in South Carolina,

Updated Children in the States 2003. According to the March of Dimes, South Carolina ranks 48th among

9

the states for infant mortality, March of Dimes Perinatal Profiles, 2003, South Carolina at 5. According to the Kids Count 2003 Data Book On line, South Carolina ranks 47th for percent of low-birthweight babies.

40 Cindy Landrum, Infant deaths prompt education for parents , T HE G REENVILLE N EWS , May 24, 2002

(“According to a report done by Kids Count, a private nonprofit foundation that studies issues facing children, South Carolina has the highest infant mortality rate in the nation, and African-American babies in the state are more than twice as likely to die during the first year of life as white babies are.” http://greenvilleonline.com/news/2002/05/24/2002052423793.htm

41 Only 62.4 percent of pregnant black women receive adequate prenatal care compared to 79.0 percent of pregnant white women. http://www.united healthfoundation.org/shr2003/states/South Carolina.html

42 Heidi Bramson, Review of data, 1996-2002, provided by the South Carolina Department of Alcohol and

Other Drug Abuse Services, on file with NAPW.

43 T HE STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL , W HITNER IMPLEMENTATION PLAN , appendix A, at 9 (1998). (Emphasis added).

44 Id at 9.

45 Drug Strategies, South Carolina Profile 12 (1998) (emphasis added).

46 As late as 2001, Mr. Condon said, “This whole program is amnesty based.”

The O’Reilly Factor (FoxNews television broadcast, Mar. 23, 2001).

47 Bert Von Herrmann, Assistant Solicitor Horry County, while Mr. Condon was the Attorney General, also claimed that “we have an amnesty program. If a person who is on crack cocaine, marijuana, has an alcohol problem or any problem and is pregnant, comes forward and seeks treatment, seeks help, we're not going to prosecute them for that.” Talk of the Nation (WNPR radio broadcast Jun. 20, 2001).

48 Transcript of Interview, Horry County Police Dept., Detective Scott Rutherford and Ms. Nikki Stephens

(Feb. 18 1999).

49 South Carolina Department of Social Services, Worker Activity and Contacts, 1998, case number:

CPS11144.

50 Burden of Proof (CNN television broadcast, Mar. 22, 2001), available at http://www.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0103/22/bp.00.html

51 Id.

52 Deposition of Stuart Axelrod, Sims v. South Carolina, February 23, 2004, at 7.

53 Id.

54 Letter from Scott R. Hixson, Assistant Solicitor, to Ms. Sims’ DSS case worker and copied to Stuart

Axelrod, Feb. 12, 2003. Mr. Hixson is the same Solicitor who did not provide any information about the existence of an amnesty program.

55 H.R. Res. H3744 1 st Sess. (S.C. 1998)

56 Self Regional Healthcare, Policy & Procedure Manual, at 7 sec. III, (1998); also, references to the procedures for drug testing and the “chain of custody” of those test samples, from Conway Hospital

Protocol, McKnight v. South Carolina, 2000-GS-26-432 and 2000-GS-26-3330, at 2

57 Michelle R. Davis, Problems With Paperwork Buy Crack Mom Time Before Prison, H ERALD , March 1,

1998, at 3B.

58 Id.

59 Id.

60 “As a matter of science, the evidence presented at trial does not even plausibly suggest – much less prove beyond a reasonable doubt – that Ms. McKnight’s ingestion of cocaine caused the stillbirth of her fetus.’

Brief Amici Curiae of the South Carolina Medical Association, the South Carolina Association of

Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Counselors, the Association of Maternal Child Health Programs et al, filed in support of Appellant, Regina McKnight, South Carolina Supreme Court. See also Brief Amici Curiae of the American Public Health Association, American Nurses Association, American Psychiatric Association,

National Stillbirth Society, South Carolina Medical Association, et. al. in support of Petitioner, on Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of South Carolina, US Supreme Court, No 02-1741 at 3 (“[T]he factual record and current state of medical science wholly fail to support any claim that Ms. McKnight’s stillbirth was caused by the ingestion of cocaine.”). Dr. Kimberly Ann Collins, Professor of Pathology and

Laboratory Medicine and Director of the Forensic Pathology the Autopsy Department at the Medical

University of South Carolina has concluded that cocaine did not cause the stillbirth; infections unrelated to drug use caused the stillbirth; and that the doctors who testified for the state at the trial had not performed the medical tests that would have allowed them to rule out numerous causes of death other than drug use.

10

McKnight v. State , Post Conviction Relief Trial, Court of Common Please 03-CP-26-5752, Transcript of

Record 134-178, (July 27, 2004).

61 http://www.state.sc.us/scdc/InstitutionPages/Institutions.htm

62 Id.

63 See Kim Baca, South Carolina spends the least on substance abuse prevention , Associated Press State &

Local Wire (Jan. 29, 2001).

64 N ATIONAL C ENTER ON A DDICTION AND S UBSTANCE A BUSE , S HOVELING U P : T HE I MPACT OF S UBSTANCE

A BUSE ON S TATE B UDGETS 81 (2001) ( available at http://www.casacolumbia.org/usr_doc/47299.pdf).

65 N ATIONAL C ENTER ON A DDICTION AND S UBSTANCE A BUSE , S HOVELING U P : T HE I MPACT OF S UBSTANCE

A BUSE ON S TATE B UDGETS 80 (2001)

66 Id.

67

South Carolina Department of Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse Services. Accountability report, fiscal year 2002-2003 . Columbia, SC: SC Dept. of Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse Services; 2003.

68 Id.

69 Id .

70 Woman charged with drug use in pregnancy, T HE M YRTLE B EACH S UN N EWS C3 (Feb. 28, 2005); Lynne

Powell, Solicitor reminds hospitals, H ERALD -J OURNAL , A1 (Dec 10, 2004).

71 E. Gaston, Conway Homicide Case Sets Precedent, T HE S UN N EWS A1 (may 19, 2001).

11