Takings 11 Loretto

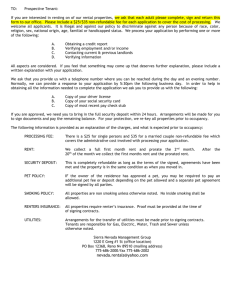

advertisement