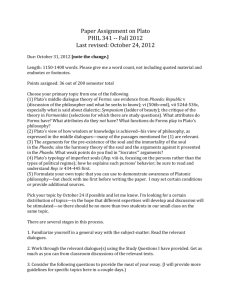

Republic – Book 1

advertisement