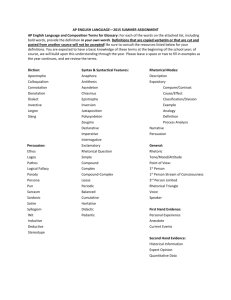

Chapter Outline - Rhetoric and Composition

advertisement

Liz Tasker Dissertation Prospectus – prepared for meeting on 5/12/2005 1 of 15 Low Brows and High Profiles: Rhetoric in the Restoration and Early Eighteenth Century Theater Although the European Enlightenment of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries touched all aspects of western culture and thought, including the rhetorical tradition, little is known about the female rhetorical activities of the Enlightenment. For much of the twentieth century, scholars of historical rhetoric viewed Enlightenment rhetoric as consisting strictly of the practice of public oratory and of written theories on the art of using language for persuasion, moral reasoning, and understanding— activities executed by men in the context of the university, the church, the law courts, and political forums. These elite venues allowed little to no participation by women; therefore, female rhetorical work during the Enlightenment appeared to be nearly nonexistent, except for that produced by a handful of females, such as Margaret Fell, Mary Astell, and Mary Wollstonecraft, who defied social conventions by speaking and writing in the traditional rhetorical genres of the sermon (Fell) and the prose treatise (Astell and Wollstonecraft). However, in the late twentieth century, a growing number of feminist historiographers and researchers began questioning and expanding the boundaries of the traditional rhetorical cannon. Studies by Glenn, Lunsford, Ronald and Ritchie, Donawerth, and Bizzell and Herzberg, among others, began reclaiming female rhetoric from Classical times to the present; much has been done in the past twenty years to expand the rhetorical cannon to include women in the classical and renaissance periods and also in the nineteenth century. But the historical record of female contributions to rhetoric during the period of the European Enlightenment, roughly the late seventeenth to late eighteenth century, is still surprisingly somewhat sparse. To rediscover the wide range of female rhetorical acts during the Enlightenment requires looking beyond the parameters of the traditional rhetorical cannon, as Andrea Lunsford recommends, for the “forms, strategies and goals used by women as rhetorical” (6). I believe an additional key to locating acts Liz Tasker Dissertation Prospectus – prepared for meeting on 5/12/2005 2 of 15 of female rhetoric in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries is to examine the rhetorical situations in which females could participate. The rhetorical situation is described by twentieth-century rhetorical theorist Lloyd Bitzer as “a complex of persons, events, objects, and relations” responding to an exigence or “an imperfection marked by urgency…a defect, an obstacle, or something waiting to done,” which can be removed or, more likely, improved or positively impacted through the means of discourse delivered by a speaker to an audience who has the power to mediate change (304). Every society and historical period has a multitude of exigencies, or problems, which its members may want to expose, debate, and mediate. Therefore, it is highly possible to use Bitzer’s concept of the rhetorical situation to reconsider the historical contexts of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to find those in which women took part and in which language was used to mediate the social issues of the period. One aspect of Enlightenment rhetoric that until recently has been largely ignored is the emergence of mixed-gender rhetorical venues, which allowed and encouraged female participation, where women were not seen as appropriating men’s rhetoric, and where the female point of view was heard and examined by everybody who participated. One such venue that has recently gained the attention of scholars of historical rhetoric is the salon, a semi-private social space that became popular in seventeenthcentury Paris and continued to flourish through the eighteenth century in both France and England (Donawerth; Bizzell and Herzberg). Salons provided places where the educated and elite of both sexes could meet and converse on topics of artistic and intellectual interest. The salon had a loosely codified set of rules for conversation, which members were expected to follow and which were entirely different than guidelines for oratory and written argumentation. One of the greatest significances of the salon is that it was one of the few venues of that time in which women had direct influence on the form and the content of rhetoric. Another socially influential, but less elite, mixed-gender rhetorical venue was the theater of the British Restoration and early eighteenth century. Some of the most influential rhetoric delivered by and about women during the long eighteenth century occurred in the theaters of London, which Charles II Liz Tasker Dissertation Prospectus – prepared for meeting on 5/12/2005 3 of 15 reopened when he was restored to the British throne in 1660 and where, shortly afterwards, he decreed that female roles would be played by female actresses rather than male actors for the first time in English history. By the late 1660s, the Restoration theater became a venue in which audiences expected women to speak and paid attention to female rhetoric. Just as women influenced the rules and content of salon rhetoric, they suddenly began to have a major influence on what was said and done on the stage. But, unlike the semi-private salon, the theater was an openly public space and, therefore, reached a much broader spectrum of society—what we now call the general public. Thus, the public debut of the actress on the English stage marked the first time in western history that a group of professional women, not just an individual female, commanded a sustained and popular public voice. This, in turn, influenced the structure and the language of public performance and had a profound impact on the female’s position as an artist and as a member of society. The overall contribution of actresses to the Restoration theater has been broadly and deeply described in several previous studies (Van Lennep 1965; Highfill, Burnim, and Langhans 1987; Howe 1992; Pearson 1988; Staves 1979). But the theater of the Restoration and early eighteenth century has not been studied from the perspective of historical rhetoric. I will use Bitzer’s theory of the rhetorical situation in conjunction with feminist historiography as the primary methodology for formulating Restoration and early 18th century theater as an important venue for rhetoric. Using Bitzer’s theory, the Restoration and early 18th century theater is easily viewed as venue in which speakers enacted responses to the deep and ongoing exigence (or defect) of gender identity in western society and in which the necessary rhetorical component of audience was ever present. The sudden prominence and popularity of the theater in the late seventeenth century London, its novel composition of players and audience, and the provocative and libertine social climate of the city created a unique historical context and rhetorical situation. From a feminist rhetorical perspective, Restoration theater gave females a public venue in which they were fully vested as speakers, as audience members, and even as the embodiment of the message itself. It has already been observed that, in Restoration and early eighteenth century theater, the actress was paramount to the message, inspiring playwrights, Liz Tasker Dissertation Prospectus – prepared for meeting on 5/12/2005 4 of 15 influencing the structure and content of the plays, and broadening the face of public discourse [The London Stage, Howe, Pearson, Weber, Staves, Hughes]. In this dissertation, I aim to build on these theater histories and to reclaim the Restoration theater as a mixed-gender rhetorical venue with its own unique and highly gender-based rhetorical forms, to claim the value of the Restoration actresses to the modern female rhetorical tradition, and to assert the validity of an interdisciplinary, belletristic stance for examining the reciprocal relationship between rhetoric, public performance and popular culture. I will examine the Restoration and early eighteenth century theater not from the perspective of theater history or simply as a genre for literary or rhetorical analysis, but as a venue for rhetorical performance and, in fact, the only public, non-elite, and secular venue available to women for public speaking and oratory in that period of English history. Of course, theatrical performance is not speech-making, except perhaps the direct address of the prologues and epilogues, but the performative nature of the theater encompasses a wide variety of rhetorical elements, including oratorical, textual, and visual. By looking at the plays, prologues and epilogues, dedications, critical reviews, and other documents describing theater performance and artistry at that time, I want to understand the rhetorical forms and strategies that were practiced and theorized and how they were informed by gender. I hope to learn more precisely how Restoration theater is significant to female rhetorical history. In the spirit of the eighteenth century belletristic movement, my approach to this study will cross multiple disciplines, including rhetoric, literary analysis, theater history, and cultural studies and will review the precedents, from the classical period to the present, for combining the study of drama and rhetoric. After examining precedents, I will then focus on the rhetorical impact of plays and performances from 1660 through 1737, the year in which the British government passed and strictly enforced a licensing act that greatly curtailed theater activity until the end of the eighteenth century. In viewing the theater of this period as rhetorical, I follow the lead started by the study of salon rhetoric to broaden our understanding of rhetorical practices in order to gain a greater insight into female participation in social and cultural issues of the long eighteenth century. Liz Tasker Dissertation Prospectus – prepared for meeting on 5/12/2005 5 of 15 Chapter Outline Abstract This section will summarize my argument and give a brief overview of the chapters. Chapter 1: Treating Drama as Rhetoric (35-40 pages) This chapter is my literature review in which I state the support and precedents for my study. At this point, I’m not sure how I will organize the chapter, but my research will cover the following areas: Classical Rhetorical Theory Aristotle - interrelationship between Rhetoric and Poetics, ideas on delivery and acting, lexis/style as related to ethos Quintilian on drama and audience Cicero – comparisons of actors and orators in The Ideal Orator Present day rhetorical studies on classical drama (Greek and Roman) 18th Century Rhetoric Belletristic Movement on literary theory, particularly drama – Blair, Smith Campbell on Drama and Wit Elocutionary Movement – Thomas Sheridan on voice and gesture Literary Theory on drama, comedy, tragedy – Dryden, Behn, 20th Century Rhetoric and Literary Theory There is a good deal of 20th century backing for arguing that the theater is a significant rhetorical venue: Feminist historiographers of rhetoric – calls for examining historic situations in which women had a voice, used language publicly, or persuaded audience - Lundsford, Glenn, Donawerth, Ritchie and Ronald, Bizzell and Herzberg, etc. Lloyd Bitzer – his original theory of the rhetorical situation: exigence (or defect) – plenty of it in the ongoing querrelle de femme of the western world audience – theater goers constraints speaker – combination of playwrights and players chiefly, also critics constituents – the theater as a space, what else? Habermas and the Public Sphere, also feminist responses to Habermas will help me define theater as a public space calls out how the philosophical-epistemological movement in rhetoric, with its direct tie to Enlightenment rationalism, became dominant—to the degradation of the belletristic movement Additional possibilities: Performance Theory? - Judith Butler, maybe Derrida, Jennifer Brody Wayne Booth – The Rhetoric of Fiction Kenneth Burke – Is dramatic pentad relevant??? –see Covino’s The Art of Persuasion Visual rhetoric – stage, body, performance, gesture Liz Tasker Dissertation Prospectus – prepared for meeting on 5/12/2005 6 of 15 Communications and media theory, reception theory of Stephen Mailloux? Edith Hamilton – The Greek Way – public spectacle and civic performance Theater History Studies of the Restoration and early Eighteenth Century Theater: Overviews: The London Stage (all components, list of performances), Actors and Actresses - Dictionary of Actors and Actresses, Elizabeth Howe Plays and Playwrights - Jacqueline Pearson, Misty Andersen (Marriage and Comedy), Harold Weber (The Rake Hero), Derek Hughes (Aphra Behn), Historic Context – 1660-1737 1660 – Charles II reopens theaters, debut of English actresses, recovery from Interregnum, licentious times through 1690s early 1700s – rise of Whig politics, mercantilism, coffee shops, investment banking 1737 – Licensing act enacts greater censorship, demand down, new play production curtailed Age of Reason, Enlightenment, Science, inductive logic, empiricism, demonstration (influence of Descartes, Bacon, Hobbes-strong influence in Restoration, later Locke) Gender issues – patriarchy: chastity, forced marriage, primogeniture Marriage and inheritance laws (or lack of) In Literature, Satire – stereotypes used to reveal individual behaviors and social conditions In Rhetoric – advances occurring on continent, Scudery, Lamy, in England- following and critiquing Locke is Mary Astell Chapter 2 –Restoration and Early 18th Century Theater: A Mixed Gender Rhetorical Venue (30 - 40 pages) This chapter will define the meaning of the term rhetorical venue and establish the Restoration theater as being one. Notes: Rhetorical venue - a forum for speakers to enact responses to an exigence to an audience who have vested interest in the issues Restoration theater as rhetorical venue – explore the deep and ongoing exigence of gender identity Constraints (defined according to Bitzer): playwrights, players, texts, relationships of these things. the advent of the actress on the public stage monarch and arts patron Charles II, marriage laws and their ambiguity, the ironic mix of patriarchy and libertinism in the social structure, the eighteenth century taste for realism and rationalism in addressing civic themes. I will simplify Bitzer’s model to: Speaker, Audience, Message, and Context (For me, context is synonymous with exigence and constraints) Liz Tasker Dissertation Prospectus – prepared for meeting on 5/12/2005 7 of 15 Theatrical Context: Overview of Rhetorical Situations generated by Theater Speaker Form/message/genre Audience Context Playwrights Written - scripts and 1. Players and rehearsal dedications crew 2. General public Playwrights/Actresses Spoken Players and Public performance of plays, crew performance prologues, epilogues Audience Spoken – immediate General public Public reaction to play and players performance Critics Written essays, General public Published texts Newspaper articles, treatises Citizens Written critique and Friends Private commentary of plays correspondence, in letters maybe published at a later date Public? No Yes Yes Yes No Theater Demographics Group Class and Gender Speakers Playwrights and actors/actresses – give percentages of male/female by decade, roles by gender, lines per play by gender, gender trends Audience Who is the audience? Mixed gender, mostly upper classes, but servants and some middle class --conflicting reports on this The Role of the Audience More discussion of Habermas – general public – popular culture – people who have no direct relationship (bourgeoisie) Wits and critics High brow and low brow As a source of revenue The Message What types of plays that were popular? New plays versus restaging of Renaissance work? Discuss new genres here or later? Chapter 3: The Speakers: Playwrights and Players (35-45 pages) Playwrights Profile of playwrights and their plays: popularity, goals, style Social influences and effects – politics and gender Writing for Particular Actors and Actresses Liz Tasker Dissertation Prospectus – prepared for meeting on 5/12/2005 8 of 15 Players Actresses and Actors as rhetoricians/ orators Language, performance and gesture/visual rhetoric Actresses Key question – Actresses in England vs. actresses in France, Spain, Italy – Did they have the same impact? Actress profiles – first-hand and second-hand accounts of oratorical strategies Roles, stereotypes, and gender identity (for each type below, talk about rhetorical styles, tropes accents, expressions, physical appearance, physical and verbal interactions with other characters): female wits and rakes virtuous heroines virgins: innocent/wanton, intelligent/ignorant, wives widows prostitutes servants Actors Actor profiles – first-hand and second-hand accounts of oratorical strategies roles, stereotypes, and gender identity: male wits and rakes virtuous heros fops and fools husbands patriarchs older and younger brothers rustics servants Chapter 4: Direct Address: Prologues, Epilogues, and Dedications (25-30 pages) This chapter should include a discussion of the structures, purpose, and rhetorical styles (dialog, tropes, imagery, motifs, etc.) for each genre/ type of dramatic piece. Dedications Prologues and Epilogues o Body references o prostitution Chapter 5: Indirect Address: Plays and their Rhetorical Maneuvers (35-45 pages) This chapter should include a discussion of the structures, purpose, and rhetorical styles (dialog, tropes, imagery, motifs, etc.) for each genre/ type of dramatic piece. Dramatic Address (indirect, subliminal) Liz Tasker Dissertation Prospectus – prepared for meeting on 5/12/2005 9 of 15 Genres and Subgenres o Comedy of Manners o She Comedies o Breeches Comedies o Burlesques o Farces o Tragedies Language: Dialog and Figurative Language o witty repartee o raillery o Metaphors Freedom/slavery Mirror – to audience Commodity metaphor Gambling/gamesters metaphors and action Chapter 6: Rhetorical Legacy of the Restoration Theater (15 pages) Relationship of media and Popular culture The rhetoric of the public self, idealized, debauched, subverted, perverted the actress as sex symbol actors and actresses as larger than life – public property – no private life vicarious interest in public personas stalkers gender identity/confusion Possible Plays for Case Study (Dr Caldwell recommended using six) Possible strategies for choosing six representative plays: Strong female presence/ storyline Mix of comedy and tragedy or just comedy? Gender identity as strong themes Interesting rhetorical strategies in prologue and epilogue and in plays Good mix of decades represented (from 1670s – 1637) Classic comedy of manners: Wycherley, William. The Country Wife. (1675) Etherege, George. The Man of Mode. (1676) Congreve, William. The Way of the World (1700) Pix, Mary. The Beau Defeated. (1700) Good gender-bender comedies: Behn, Aphra. The Rover (1677) Southerne, Thomas. Sir Anthony Love (1690) Tragedies with gender issues: Otway, Thomas. Venice Preserved. (1682) Dryden, John. All for Love. (1677) Rowe, Nicholas. The Fair Penitent. (1703) Others – good for various reasons: Centlivre, Susanna. The Gamester. __________. The Basset Table. Fielding, Henry. The Actor’s Farce (1730s?) Gay, John. The Beggar’s Opera. (1728) Liz Tasker Dissertation Prospectus – prepared for meeting on 5/12/2005 Bibliography This is still very rough Restoration and 18th Century Drama Behn, Aphra. The Rover: or The Banished Cavaliers.(1677) __________. The Lucky Chance. __________. The Rover Part 2. (1681) Centlivre, Susanna. Bold Stroke for a Wife. (1718) __________. The Gamester. __________. The Basset Table. Cibber, Colley. Love’s Last Shift. (1696) Congreve, William. The Way of the World (1700) Dryden, John. All for Love. (1677) Etherege, George. The Man of Mode. (1676) Farquhar, George. The Beaux’s Strategem. (1707) Fielding, Henry. The Author’s Farce (1730s?) Gay, John. The Beggar’s Opera. (1728) Otway, Thomas. Venice Preserved. (1682) Pix, Mary. The Beau Defeated. (1700) Rowe, Nicholas. The Fair Penitent. (1703) Southerne, Thomas. Oroonoko. (1695) ___________. Sir Anthony Love. (1690) Vanbrugh, John. The Relapse. (1696) Wycherley, William. The Country Wife. (1675) Drama of Previous Periods (needed for comparison) Classical Aeschylus Aristophanes. The Frogs. Euripides. The Bacchae. Sophocles Renaissance Shakespeare – The Taming of the Shrew. Twelfth Night. MacBeth. Antony and Cleopatra. Romeo and Juliet. French – Moliere??? 10 of 15 Liz Tasker Dissertation Prospectus – prepared for meeting on 5/12/2005 11 of 15 18th Century Rhetoric Astell, Mary. A serious proposal to the ladies. Parts I & II. Ed. Patricia Springborg. Brookfield, VT: Pickering & Chatto, 1997. Blair, Hugh Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres. Selections from The Rhetoric of Blair, Campbell, and Whately. Ed. James Golden and Edward P. J. Corbett. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 1990. Campbell, George. The Philosophy of Rhetoric. 1776. Rpt. Delmar, NY: Scholars' Facsimiles and Reprints, 1992. Hobbes, Thomas. The Leviathon Hume, David. "Of the Standard of Taste" in Essays Moral, Political, and Literary. Indianapolis, IN: LibertyClassics, 1987. Locke, John. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding de Scudery, Madeleine . “Of Conversation” The Rhetorical Tradition: Readings from Classical Times to the Present. . Ed. Patricia Bizzell and Bruce Herzberg. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2001. 767-772. ___________________. The Story of Sapho. Trans. Karen Newman. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press (2003). Sheridan, Thomas. A Course of Lectures on Elocution. Delmar, NY: Scolars Facsimiles & Reprints, 1991. Smith, Adam. Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres...Reported by a Student in 1762-3, ed. J.C. Bryce. Oxford: Clarenden Press, 1983. Theater History, Theory, and Criticism Anderson, Misty G. Female Playwrights and Eighteenth Century Comedy: Negotiating Marriage on the London Stage. New York: Palgrave, 2002. Avery, Emmett L. “Rhetorical Patterns in Restoration Prologues and Epilogues.” Essays in American and English Literature Presented to Bruce Robert McElderry, Jr.. ed. Max F Schulz, William D Templeman, and Charles R. Metzger. Athens: Ohio UP, 1968. 221237. Collins, Margo. “Centlivre v. Hardwicke: Susannah Centlivre’s Plays and the Marriage Act of 1753.” Comparative Drama. 33 2. 1999. Liz Tasker Dissertation Prospectus – prepared for meeting on 5/12/2005 12 of 15 Corporaal, Marguérite. “'Thy Speech Eloquent, Thy Wit Quick, Thy Expressions Easy: Rhetoric and Gender in Plays by English Renaissance Women.” Renaissance Forum: An Electronic Journal of Early Modern Literary and Historical Studies, 2003 Winter; 6 (2). Feldwick, Arlen. “Wits, Whigs, and Women: Domestic Politics as Anti-Whig Rhetoric in Aphra Behn’s Town Comedies.” Political Rhetoric, Power, and Renaissance Women. Eds. Carole Levin and Patricia A. Sullivan. New York: State University of New York Press, 1995. 223-242. Goodden, Angelica. Actio And Persuasion : Dramatic Performance In Eighteenth-Century France. 1986. Gunderson, Erik. Staging Masculinity : The Rhetoric Of Performance In The Roman World. 2000. Hayes, Douglas W.. Rhetorical Subversion in Early English Drama. New York: Peter Lang, 2004. Highfill, Philip H., Kalman A. Burnim, Edward A. Langhans. A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers & Other Stage Personnel in London, 1660-1800. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1987. Howe, Elizabeth. The First English Actresses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1992). Hughes, Derek. The Theatre of Aphra Behn. Houndmills: Palgrave, 2001. Kreis-Schink, Annette. Women, Writing, and the Theater in the Early Modern Period: The Plays of Aphra Behn and Suzanne Centlivre. London: Associated University Presses, 2001. Longman, Stanley Vincent, ed. Theatre symposium Vol. 5, Drama as rhetoric/rhetoric as drama : an explanation of dramatic and rhetorical criticism: a journal of the Southeastern Theatre Conference. 1997. Lowenthal, Cynthia. “Sticks and Rags, Bodies and Brocade: Essentializing Discourses and the Late Restoration Playhouse.” Broken Boundaries: Women and Feminism in Restoration Drama. ed. Quinsey, Katherine M.. Lexington: UP of Kentucky, 1996. 219-33. Maus, Katharine Eisaman. “Playhouse Flesh and Blood: Sexual Ideology and the Restoration Actress.” ELH, 1979 Winter; 46 (4): 595-617 Payne, Deborah C.. “Reified Object of Emergent Professional? Retheorizing the Restoration Actress.” Cultural Readings of Restoration and Eighteenth-Century English Theater. J. Douglas Canfield and Deborah C. Payne, ed.. Athens: U of Georgia P; 1995. 13-38. Pearson, Jacqueline. The Prostituted Muse: Images of Women and Women Dramatists 1642-1737, New York: Harveister Wheatsheaf, 1988. Liz Tasker Dissertation Prospectus – prepared for meeting on 5/12/2005 13 of 15 Staves, Susan. Players’ Scepters: Fictions of Authority in the Restoration. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1979. Van Lennep, ed. London Stage 1660-1800: Part 1:1660-1700. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1965. Weber, Harold. The Restoration Rake-Hero. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1986. Worthen, William B., Modern Drama and the Rhetoric of Theater. 1992. Classical Rhetoric and Poetic Aristotle, Poetics ___________. On Rhetoric Longinus. On The Sublime (excerpted in Bizzell/Herzberg); Cicero, On The Ideal Orator, edited and translated by James M. May and Jakob Wisse, Oxford UP, 2001. Quintilian. Institutes of Oratory: or, Education of an Orator. Contemporary Theory (Rhetorical, Feminist, and Literary) Bizzell, Patricia and Bruce Herzberg, ed. The Rhetorical Tradition: Readings from Classical Times to the Present. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2001. Bizzell, Patricia. “Feminist Methods of Research in the History of Rhetoric: What Differences Do They Make?” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 30.4 (Fall 2000): 5-17. ___________. “Praising Folly: Constructing a Postmodern Rhetorical Authority as a Woman.” In Feminine Principles and Women’s Experience in American Composition and Rhetoric. Ed. Louise Wetherbee Phelps and Janet Emig. U of Pittsburgh P, 1995. 27-42. Carstarphen, Meta G. and Susan C. Zavoina., ed. Sexual Rhetoric : Media Perspectives on Sexuality, Gender, and Identity. 1999. Connors, Robert J. “Dreams and Play: Historical Method and Methodology.” In Methods and Methodology in Composition Research. Eds. Gesa Kirsch and Patricia A. Sullivan. Southern Illinois UP, 1992. 15-36. Covino, William A. The Art of Wondering: A Revisionist Return to the History of Rhetoric. Boynton/Cook, 1988. ___________. The Elements of Persuasion. Allyn & Bacon/Longman, 1998. Liz Tasker Dissertation Prospectus – prepared for meeting on 5/12/2005 14 of 15 Donawerth, Jane. “Conversation and the Boundaries of Public Discourse in Rhetorical Theory by Renaissance Women.” Rhetorica. 16:2 (1998). 181-199. ___________. “As Becomes a Rational Woman to Speak: Madeleine de Scudery’s Rhetoric of Conversation.” Listening to Their Voices: The Rhetorical Activities of Historical Women. 1997. ___________. “The Politics of Renaissance Rhetorical Theory by Women.” Political Rhetoric, Power, and Renaissance Women. Eds. Carole Levin and Patricia A. Sullivan. New York: State University of New York Press, 1995. 257-272. Donawerth, Jane, ed. Rhetorical Theory by Women Before 1900. Rowman and Littlefield, 2002. (this is an anthology; read introduction) Enos, Richard. “Recovering the Lost Art of Researching the History of Rhetoric.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 29.4 (Fall 1999): 7-20. Enos, Theresa, ed. Learning from the Histories of Rhetoric: Essays in Honor of Winifred Bryan Horner. Southern Illinois UP, 1993. Glenn, Cheryl. Rhetoric Retold: Regendering the Tradition from Antiquity Through the Renaissance Lunsford, Andrea. “On Reclaiming Rhetorica.” Reclaiming Rhetorica: Women in the Rhetorical Tradition, ed. Andrea A. Lunsford. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1995. 3-8. Paxson, James J. “Personification’s Gender.” Rhetorica 16.2 (1998): 149-79. Poulakis, Takis, ed. Rethinking the History of Rhetoric: Multidisciplinary Essays on the Rhetorical Tradition. Westview Press, 1993. Ritchie, Joy S. Available Means: An Anthology of Women's Rhetoric Vitanza, Victor J., ed. Writing Histories of Rhetoric. Southern Illinois UP, 1994. Wertheimer, Marjories, ed. Listening to their Voices: The Rhetorical Activities of Historical Women. U of South Carolina P, 1997. Readings for Connecting Rhetoric and Poetics Hamilton, Edith. The Greek Way and The Roman Way Jarratt, Susan C. “Sappho’s Memory.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 32.1 (Winter 2002): 11-43. Jarratt, Susan, and Susan Romano. “Peitho Revisited.” Peitho: The Newsletter of the Coalition of Women Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition 7.2 (Spring/Summer 2002): 10. Kallendorf, Craig, ed. Landmark Essays on Rhetoric and Literature. Hermagoras Press, 1999. Liz Tasker Dissertation Prospectus – prepared for meeting on 5/12/2005 15 of 15 Kennedy, George A. Comparative Rhetoric. NY: Oxford UP, 1998. ___________. A New History of Classical Rhetoric. Princeton UP, 1994. Kirby, John T. “ ‘The Great Triangle’ in Early Greek Rhetoric and Poetics.” Rhetorica III.3 (Summer 1990): 213-28. Walker, Jeffrey. Rhetoric and Poetics in Antiquity. Oxford UP, 2000. Readings related to the “The Public Sphere” Bracci, Sharon L. and Clifford G. Christians, ed. Moral Engagement in Public Life: Theorists for Contemporary Ethics. 2002. Crossley, Nick, et al., eds. After Habermas: New Perspectives on the Public Sphere. Blackwell Publishers, 2004. Fraser, Nancy. Fraser, Nancy. “Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy.” In Postmodernism and the Re-Reading of Modernity. Ed. Francis Barker, Pete Hulme, and Margaret Iverson. NY: St. Martin’s Press, 1992. 197-231. Gaillet, Lynee Lewis. “Public Literacy, Social-Process Inquiry and Rhetorical Intervention: Viewing Students (and Ourselves) as Public Intellectuals.” Composition Studies 30.2 (Fall 2002): 127-36. Habermas, Jurgen. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgois Society. MIT Press, 1991 (reprint) Hauser, Gerard. Vernacular Voices: The Rhetoric or Publics and Public Spheres. U of South Carolina P, 1999. Weisser, Christian R. Moving Beyond Academic Discourse: Composition Studies and the Public Sphere. Southern Illinois UP, 2002.