Warren G. Harding

advertisement

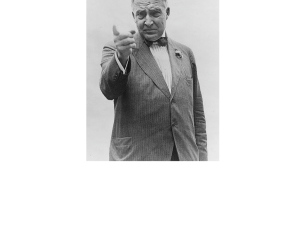

Warren G. Harding Harding was an easy-going politician who believed that the Republican Party could bring the United States back to "normalcy," a word he invented. By normalcy he meant a return to the economic and political isolation that had characterized the United States before it entered World War I in 1917. Harding never showed the leadership or vision required to be an effective president, and his administration is mainly remembered for its corruption, which was revealed after Harding's death. Early Political Career In the 1890s Harding increased his social and business connections in Marion. He joined the Masons, the Elks, and other fraternal orders. He served as a director of the Marion County Bank, the Marion County Telephone Company, and Marion Lumber Company, and he was a trustee of the Trinity Baptist Church. The influence of his newspaper, his public speaking ability, his friendly personality, and his interest in public affairs brought Harding to the attention of local and state politicians. He joined the state Republican Party, and in 1898 and 1900, Harding was elected to the Ohio State Senate. By this time he had become friendly with Harry M. Daugherty, an influential lawyer and politician. In 1903 Daugherty helped get Harding elected lieutenant governor of Ohio. After serving a two-year term, Harding retired from politics until 1910, when he lost a campaign for governor. In spite of this defeat, Harding remained well liked by Republican politicians. In 1912 President William Howard Taft, a fellow Ohioan, asked Harding to nominate Taft at the Republican National Convention for a second term as president. In the subsequent campaign, Harding vigorously attacked former President Theodore Roosevelt, who had left the party to run as the candidate of the Progressive, or Bull Moose, Party. The issue of party loyalty seemed to have been more important to Harding than the defeat of the Democratic candidate, Woodrow Wilson, who won the election. In 1914, with Daugherty's help, Harding gained the Republican nomination to the U.S. Senate. In November he won the election by a large margin. Election of 1920 Late in 1919, Daugherty, then the Republican leader in Ohio, started a well-planned Hardingfor-president movement. Harding's name was entered in presidential primaries, and the senator from Ohio made speeches around the country. On May 14, 1920, Harding announced that the nation needed "not nostrums but normalcy." The slogan "return to normalcy" expressed the yearning of some Americans for the unrestrained free enterprise, the untaxed incomes, and the high import tariffs of the past. It also meant a nation isolated from troublesome world affairs or, as Harding put it, "not submergence in internationality but sustainment in triumphant nationality." The Democrats naturally disagreed with Harding's views. William Gibbs McAdoo, secretary of the treasury from 1913 to 1918, summed up their reaction by calling Harding's speeches "an army of pompous phrases moving over the landscape in search of an idea." Harding won the election by a record-breaking margin of 7 million votes over Cox, an amazing total of more than 60 percent of all votes cast. He received 404 electoral votes to Cox's 127 and carried every state except those in the solidly Democratic South. Harding's Appointments Three of the men whom Harding appointed to his Cabinet were very well qualified. Charles Evans Hughes, a former associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court and the Republican presidential candidate in 1916, was an outstanding appointment as secretary of state. Henry Cantwell Wallace, an agricultural expert of irreproachable character, was a fine choice for secretary of agriculture. Future President Herbert Clark Hoover, a capable and dedicated man who had been serving as the chairman of the American Relief Administration and the European Relief Council, was named secretary of commerce. Several other appointees, if less distinguished than these three, were experienced and respected men. A few important posts were given to untrustworthy men to pay political debts. In this category were the appointments of Daugherty as attorney general, Senator Albert B. Fall of New Mexico as secretary of the interior, and former representative Edwin Denby of Michigan as secretary of the navy. For positions of less than Cabinet rank, Harding often chose personal associates. His group of friends, who came to be known as the Ohio Gang, included Charles R. Forbes, the head of the Veterans Bureau, and E. Mont Reily, the governor of Puerto Rico. Although there is no proof that Harding himself was corrupt, his good nature and self-indulgent character seem to have blinded him to corruption in others. Domestic Affairs In domestic legislation, Harding followed his usual conservative course. He supported the repeal of the wartime tax on excess profits and the reduction of income taxes on the wealthy. He signed the high tariff Fordney-McCumber Act of 1922 and proposed measures to relieve an agricultural depression that began in 1920. He also approved the Immigration Restriction Act of 1921, which first established an immigration quota system. Each European nation was assigned an annual number of immigrants equal to 3 percent of the number from that country residing in the United States in 1910. Most Asians were already barred. Harding disapproved of radicalism of any sort and the four justices he appointed to the Supreme Court of the United States were able but very conservative men. Foreign Affairs The president called a special session of Congress in April 1921, soon after his inauguration. The two major items for consideration were the peace with Germany and a treaty with the Republic of Colombia. By joint resolution of the houses of Congress the war with Germany was declared at an end. The resolution claimed for the United States all "rights and advantages" obtained by the Allies in the Versailles Treaty. However, it rejected any responsibilities assumed in the treaty by the Allies. The treaty with Colombia proposed a payment to that country of $25 million for the loss of Panama. Panama had won its independence from Colombia in 1903 with the help of the United States. Senator Lodge, who oversaw such issues as the chairman of the powerful Committee on Foreign Relations, urged adoption of the treaty to soothe Colombia and to obtain drilling rights there for U.S. oil companies. The treaty was ratified by the Senate in April 1921. The best-known accomplishment of the Harding administration in foreign affairs was an international disarmament meeting, the Washington Conference, held in Washington, D.C., in 1921 and 1922. The conference resulted in several treaties. The Five-Power Treaty established limits on the number of tons of ships and aircraft carriers that the United States, Great Britain, Japan, France, and Italy might maintain. In the Four-Power Pact the United States, Britain, France, and Japan agreed to respect one another's island possessions in the Pacific. The United States also signed the Nine-Power Treaty, which promised that the independence and territory of China would not be violated and that the Open Door Policy, which promised equal commercial opportunities in China to all nations, would be respected by those who signed the treaty. Corruption In March 1923 the first scandal of the Harding administration was revealed. A month earlier, Harding's friend Forbes, the head of the Veterans' Bureau, had resigned his post and left the country. An investigation found that he and his accomplices had robbed the government of $200 million. The Veterans' Bureau chief was soon brought back to the United States and, in 1925, was sentenced to prison. Other scandals followed the Veterans' Bureau scandal. It was rumored that officials of the Justice Department were taking bribes to protect violators of the Prohibition laws. A Senate investigation revealed that Attorney General Daugherty had illegally made a profit by allowing alcohol to be taken from government supplies. There was also corruption in the office of the Alien Property Custodian. The president appeared unnerved and despondent as the scandal involving his administration came to light in the spring of 1923. Teapot Dome Scandal Also in 1923, the most flagrant example of corruption in Harding's administration was about to be revealed. In 1921 Harding had been induced by Secretary of the Navy Denby to sign an order that transferred control of the naval oil reserves stored at Teapot Dome near Casper, Wyoming, and at Elk Hills, California, from the Navy Department to the Department of the Interior. In 1922 Secretary of the Interior Fall leased the Elk Hills reserves and the Teapot Dome fields without competitive bidding. The Senate investigation that began in 1923 revealed that Fall had received more than $400,000 from oil companies for his services. Although the Senate did not investigate the oil leases until after Harding's death, the president was aware of the trouble within his administration. He spoke to Hoover and others about the sad position of a man who has been betrayed by those he trusted. His health suffered from the strain. In June 1923, when Harding and his wife began a trip to Alaska, the president appeared tense and worn. During the cross-country journey he further weakened himself by making 85 speeches. On the way back from Alaska he fell sick. His doctors insisted on complete rest, and the presidential party stopped in San Francisco. There, at the Palace Hotel, on July 29, Harding collapsed, and died four days later. Although no autopsy was performed, an attending physician announced that President Harding had died of an embolism. His vice president, Calvin Coolidge, succeeded him as president when he took the oath of office on August 3, 1923.