I'm a teacher - The Good, the Bad and the Economist

advertisement

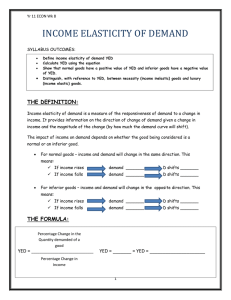

Chapter 11: Income elasticity of demand (1.2) Key concepts: Definition of income elasticity of demand (yED) Formula for income elasticity of demand Normal goods Inferior goods Applications of income elasticity of demand The concepts income and demand are inextricably linked, just like having a good day on the stock markets and celebrating with a nice cigar and bottle of Champagne. One is unlikely to celebrate by going out and splurging on, say… potatoes!1 This is what income elasticity looks at; the propensity to change one ’s consumption of certain goods due to a change in income. Income elasticity of demand measures how responsive quantity demanded is to a change in income. Definition of income elasticity of demand (yED) The issue at hand is to relate a change in quantity demanded with an increase in income, i.e. the percentage change in quantity demanded over the percentage change in income. Most goods will behave normally, which is, the quantity demanded will increase as income increases. However, some goods will actually behave in an opposite manner; quantity demanded will fall when income rises. Therefore, just as in crossprice elasticity, we are interested not only in the value of elasticity, but also the sign. <Def> Definition: Income elasticity of demand Income elasticity of demand – yED – measures the responsiveness of demand, i.e. the relative (percentage) change in the quantity demanded for a good due to a relative (percentage) change in income. (The lower case “y” signifies personal income, since upper case “Y” is reserved for national income.) <End def> Formula for income elasticity of demand The formula for income elasticity is nothing new – we simply replace “relative change in price” with “relative change in income”. I urge you again; beware of the sign of yED! Q 1 – Q0 ------------------- 100 Q0 % in Qd yED = ------------------------ ----------------------------------% in y y 1 – y0 ---------------- 100 y0 1 Unless you’re Swedish or Irish. Normal goods The last time I almost resigned (or was almost fired – these seem to be complement goods in my case) I stormed home and told my then wife that a number of planned expenditures would have to be dropped. The mere whiff of less income caused a change in purchasing behaviour. As soon as I was re-hired (with the mediator help of Joe Cool, the Irish math teacher) my household’s buying plans went right back on track. This is how consumers are prone to act – and all the goods whose quantity demanded fell and rose in concert with my income are normal goods. The definition of a normal good is that it is positively related to income. Most goods are normal goods, but there are a few possible exceptions.2 <Def> Definition: Normal good A normal good is positively correlated to income, i.e yED is positive. A rise in income increases demand for normal goods. A fall in income decreases demand for normal goods. <End def> An income-elastic good is a good for which quantity demanded rises proportionately more than an increase in income, i.e. income elasticity is greater than +1. High market goods such as vintage wines and luxury goods are income elastic, as are services and tourism. At the other end of the spectrum are goods where the increase in quantity demanded is proportionately less than the increase in income; income inelastic goods, which have values of income elasticity less than +1. Commonly referred-to examples are clothing and cigarettes. I figure you are all big boys and girls now, so I shall forgo all the formulaic usage and confine myself to examples based on percentages. Let us assume that income for a specified group of consumers rises by 10% - which is a bit unrealistic but makes the calculations easier. If quantity demanded for vintage wines from Bordeaux increases by 20% we get a yED of +2; an increase of vegetable consumption by 2% renders a yED of +0.1. Quite naturally, income elasticities will vary between high and low income groups and more significantly perhaps, between high and low income countries. Food, for example, has an income elasticity of between +0.5 and +0.6 in LDCs while most MDCs hover between +0.2 and +0.5.3 What might be considered a luxury good in rural China, a bicycle for example, would have a correspondingly high income elasticity of demand whereas a MDC would most assuredly have a lower income elasticity of demand for such a good. In line with this, development and accompanying higher incomes will change the pattern of income elasticities away from basic commodities towards manufactured goods and services. Inferior goods A good where quantity demanded falls as income rises is known as an inferior good, the term being used not as a descriptor of the good per se, but rather as a descriptor of our relative consumption preferences at higher income levels. Potatoes are not ‘inferior’ to pasta yet when incomes rise evidence suggests that our relative preferences will cause us to actually lower our consumption of potatoes and substitute the good with something preferable. Potatoes might thus have a negative income elasticity of demand, as an increase in income is correlated to decreased quantity demanded. <Def> Definition: Inferior good An inferior good is negatively correlated to income, i.e. the yED is negative. A rise in income decreases demand for inferior goods. A fall in income increases demand for inferior goods. <End def> 2 This goes for school headmasters also. 3International Evidence on Consumption Patterns 1989, Greenwich, Connecticut JAI Press Inc. It is worth commenting on the possibility that many goods are in fact normal up to certain incomes and thereafter inferior. At low levels of income, any addition to income might mean increased quantity demanded for basic goods such as food and clothing. However, at some point at higher level income, the quantity demanded for such goods would surely not proportionally match an increase in income. Just imagine how the yED values for economics students at university would change upon getting a good job in London City after graduation. An oft-cited concept within the context of inferior goods is the aforementioned Giffen good, i.e. a good where quantity demanded is positively correlated to price. This would be a type of inferior good… but I ’ve just decided that it would be a waste of time explaining this, as Giffen goods invariably wind up in the same category as mermaids, goblins and UFOs. In the previous edition of this book I declared an international boycott against the use of the term ‘Giffen Good ’. Somebody in the IBO seems to have caught on since this ridiculous concept has since disappeared from the syllabus! I rule. POP QUIZ 2.2.3: INCOME ELASTICITY 1. How will demand for inferior goods in an economy be affected if a) incomes rise, b) unemployment decreases c) the general price level rises? (Treat each as a separate case.) 2. You read in the newspaper about a good with ‘…an elasticity of -2’. Explain why you need more information about the type of elasticity since ‘-2’ can actually be referring to two entirely different goods! 3. Must income elasticity of demand be solely positive or solely negative? Illustrate your answer with a diagram. Applications of income elasticity of demand Income elasticities play an important roll in illuminating the problems of less developed countries (LDCs) caught in producing primary goods. A solid grasp of how income affects consumption preferences is central to understanding how economic growth influences trade and development. LDCs are highly dependent on the production of primary commodities. 71% of non-Asian LDCs’ exports are made up of primary goods.4 Yet the same countries account for just 12% of total world trade and 17% of total world GDP (1998 figures).5 Summing this up paints a picture of a group of counties whose output is exported mainly to rich countries, and where the demand for these primary goods is highly dependent on growth rates in high-income countries. As average global incomes increase, demand for goods with high yED (secondary and tertiary goods) will rise faster than for goods with low yED (primary goods). 4Todaro, 5The p 68 World Economy, A millennial perspective, OECD, table 3-1c, page 127 This paints an important picture of relative prices; the price of secondary goods will rise faster than prices of primary goods. In economic lingo, primary goods become relatively cheaper than secondary goods. Economies specialising in primary goods will now see that increasing quantities of, say, coffee must be exported in order to import any given amount of machinery. The price of exports relative to the price of imports is known as the terms of trade. As export prices fall in relation to import prices, the terms of trade worsen for primary goods specialists. Summary and revision (need a cool pic here….maybe a pic of someone doing pushups!) 1. Income elasticity of demand (yED) shows the sensitivity of demand for a good with respect to a change in income 2. The formula for yED is (Marcia, please cut in the % ∆Qd /% ∆ y here) 3. A positive value of yED means the good is a normal good i. Normal goods in diagrams; an increase in income leads to an increase in demand (demand curve shifts right) 4. A negative value of yED means the good is an inferior good i. Inferior goods in diagrams; an increase in income leads to a decrease in demand (demand curve shifts left) 5. LDCs are often producers of primary goods which have low income elasticities of demand. As incomes in developed countries increase, demand for primary goods increase proportionally less. As prices for secondary goods – which have a higher income elasticity of demand – rise more than prices for primary goods, LDCs will have to export more primary goods for any given quantity of imported of secondary goods. This means that the terms of trade for LDCs worsens.