The Pubic Utility Holding Act of 1935

advertisement

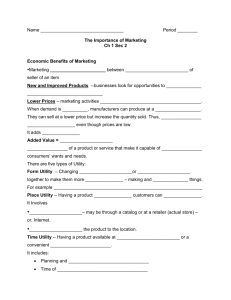

Expanding Public–Private Partnerships in Electric Railways: A Zero-Cost Conservative Proposal By William S. Lind and Glen D. Bottoms Prepared For Copyright © 2012 American Public Transportation Association • 1666 K Street NW, 11th Floor, Washington, DC 20006 INTRODUCTION Were we to go back to the America of one hundred years ago - - something we , as conservatives, wish we could do - we would find that few Americans had automobiles. But Americans of 1911 were very much on the move. People got around cities, from countryside to city and from one city to another. They did so easily, comfortably and frequently. How? On railways. While almost all intercity passenger trains were pulled by steam locomotives - - some of which could hit 100 MPH - streetcars and interurbans were electrically powered. In fact, the revolution in personal mobility began not with Henry Ford’s Model T, but twenty years earlier with the combination of the safety bicycle (the kind with two equal-size wheels, which was the first bicycle clothes-constrained women of the era could ride) and the electric railway. With gas likely to be more expensive in years to come, many of us wish we still had the thousands of miles of electric railways we had then. What happened to them? How did we become a country whose national motto seems to be “Drive or Die?” 2 The answer, in a word, is government. For almost a century, since the federal Good Roads Act of 1916, government has consistently favored highways over railways. It built government-funded highways (by 1920, government was already subsidizing highways with more than a billion dollars a year) at the same time that it taxed railways, virtually all of which were privately owned and received no subsidies. Conservatives know what happens when government subsidizes one competitor while taxing another. We also know that the inevitable result is not a free market outcome. But that was not all government did to favor highways over railways. In August, 1935, the Roosevelt Administration succeeded in having Congress pass an obscure piece of legislation that led to the demise of hundreds of electric railways all over the country. Called the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935, the law did not intend to have the effect it did on streetcar and interurban lines. In fact, it seems Congress never considered its possible effects on public transportation. But when the Act’s disastrous impact on electric railways manifested itself, neither the administration nor Congress seemed to notice. They took no action to modify the Act. Quite the contrary, even though the 1935 Act was modified in 1992 and replaced with new legislation in 2005, our research indicates that some of the provisions which did so much damage to electric railways remain in effect today - - with continuing consequences. Care to 3 guess how long legislation that had massive negative effects on highways would remain on the books? As conservatives, we know that a market economy requires a level playing field. We also want to see private capital take as large a role as possible in providing public services, including transportation. In this study, we explore how the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 drove private capital out of the electric railway business, and how finally addressing the Act’s unfortunate consequences might re-open the door - - at no cost, and with the prospect of considerable savings to the taxpayer. The Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 To understand why the 1935 Act had such disastrous consequences for electric railways, we need to drop back a bit, all the way to the 1890s when new electric streetcar lines and interurbans were being built all over the country. At that time, outside major cities, most homes and businesses had no access to electric power. But streetcars and interurbans ran on electricity. To generate the power they needed, the interurban and streetcar companies built their own electric power systems, with power plants where steam engines turned electric generators, transmission lines that ran along the 4 whole rail line and substations to boost the power supply at regular intervals. Suddenly, outlying neighborhoods and towns did have electric power. And because streetcars and interurbans did not need all the electricity the generators could produce, the companies began selling the surplus to homes and businesses. The trolley industry played a significant (and often unrecognized) role in electrifying America. As the demand for power grew and electric railways provided it, many companies changed. They became both power companies and electric railways. Their names often reflected this, e.g., The Milwaukee Electric Railway and Light (TMER&L) Company. Over time, the electric utility business became the larger part of what they did - - and of their revenues. By the 1920s and early 1930s, the profits from selling electricity were cross-subsidizing the electric railways, which had in many cases become money-losers - - thanks to competition from government-funded highways. The 1935 Act prohibited such cross-subsidization. Indeed, the Act forced the integrated transportation and electric power companies to choose: they could be one or the other but not both. 5 The law, also known as the Wheeler-Rayburn Act, was passed in August, 1935 and most provisions went into effect on January 1, 1938. Considered a crowning achievement of Roosevelt’s New Deal, the Act was a reaction to the abuses that some public utility holding companies had perpetrated in the gogo 1920’s and the hard crash they (and their numerous stockholders) suffered during the Great Depression. Fifty-three public utility holding companies went bankrupt - - of which the Samuel Insull empire, owner of numerous interurban lines, was the most notable - - and twenty-three others defaulted on interest payments.1 In the failure of the Insull empire alone, 600,000 investors lost their life savings. The law sought to safeguard the financial health of public utilities. Many of the public utility holding companies that failed had engaged in risky behavior, owning or investing in tempting business ventures around the world which had nothing to do with their core business, generating and selling electric power. The Act required each utility holding company to limit its operations to a single integrated public utility system (generating, distributing and selling electric power) operating within one state or in contiguous states. It also prohibited cross-subsidization within pubic utility holding companies. As the Act was interpreted by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and upheld by the courts, this required that 6 public utilities choose between their profitable electric power operations and their often money-losing electric interurban railways and streetcar systems. It appears that Congress, in considering the legislation, did not even think about the potential effects of the proposed law’s provisions on electric rail transit properties. Indeed, as recently as 1993, a comprehensive study of the Act by the Energy Information Administration failed to mention the effects of the law on public transportation. David St. Clair, in his seminal work, The Motorization of American Cities, estimated that the Act’s consequences in some way impacted 50 percent of transit companies carrying about 80 percent of total revenue passengers in 1931.2 The number of public utility holding companies declined from 216 in 1938 to just 18 in 1950.3 Within those that remained, the internal cross-subsidies that had kept many electric railways alive were no longer allowed. Over a hundred electric railways, both interurbans and streetcar systems, closed down or were sold for a song. Once sold, streetcar companies lost access to fresh capital from the parent utility company and suffered a demoralizing drain of choice managerial talent, which reverted to the parent utility company when the streetcar company assets were sold.4 7 A former executive with Ohio’s largest electric utility, American Electric Power, tells the story: The Holding Company Act dramatically changed the landscape for utilities with the requirement that the systems had to be interconnected and contiguous. This Act required American Gas and Electric (now AEP) to sell properties in Atlantic City and Scranton, PA and focus on its properties in the Midwest. It also required that Holding Companies could only own properties that were useful in the generation, transmission and distribution of electrical energy.5 Electric railways did not meet that test. In 1922, America had 28,906 miles of street railway track. By 1950, that number had declined to 8,071, a 72% decrease.6 In 1930, Americans traveled on 55,150 streetcars. By 1950, only 13,288 were left.7 The Public Utility Company Holding Act was not the only reason for that dramatic decline, but it was a major contributor. While government actions that favored highways over public transportation were the major driver of today’s automobile dominance, the 1935 Act also opened the door for the auto industry to slip in the knife. When the Act forced public utility holding companies to get rid of their electric railways, many chose to sell rather than abandon them. The prices they asked were often pitifully 8 low, reflecting not the value of the electric railways’ service to the public but the fact that few had made a profit in years. General Motors had actually begun financing buyouts of rail transit properties in small and medium-sized cities as early as 1930. In 1936, the automobile industry as a whole, represented by General Motors, Firestone Rubber, Standard Oil and Phillips Petroleum, banded together to form their own holding company, National City Lines (NCL), and associated affiliates/subsidiaries [American City Lines- ACL; and Pacific City Lines- PCL]. NCL moved quickly to buy up many small and medium-sized electric railways and convert them to buses. Numerous electric railways were destroyed in this manner. The purpose was not to sell buses (although acquired properties were required to purchase GM-manufactured buses) but to sell cars. GM and its allies knew that the quality of service provided by buses did not approach that given by electric railways so that most people, if faced with riding a bus, would opt to buy a car instead. Of course, while the holding companies that had kept so many electric railways alive were outlawed, National 9 City Lines, also a holding company, faced no such restrictions. A Case Study Ironically, one of the victims of the Act was the city where it was passed, our nation’s capital. After the 1935 merger of the two main streetcar companies in Washington, DC, the local transit company that emerged, Capital Transit, was owned by the North American Company, a public utility holding company. The North American Company controlled 80 corporations engaged in a variety of activities besides generating electric power, including amusement parks and coal mines.8 North American ownership of Capital Transit was realized through the wholly owned Washington Electric Railway Company which owned 50% of Capital Transit and 100% of the Potomac Electric Power Company (PEPCO).9 PEPCO supplied electric power to the District of Columbia and parts of the Maryland suburbs. North American sought relief in the courts from the Act, claiming that the SEC’s ability to confine the company’s operation to a single integrated utility amounted to a taking without proper compensation. The Supreme Court eventually upheld the Act, ruling in 1946 that North American would have to divest itself of its extensive holding of power companies and other enterprises across the country, including Capital Transit.10 10 It was widely known at the time that the North American Company was dedicated to making transit in the nation’s capital a showcase, and the operation was acknowledged as one of the premiere transit properties in the country. Capital Transit was also profitable. Unfortunately, to comply with the Supreme Court ruling, North American was to unload Capital Transit in 1948 to a business consortium led by Louis Wolfson, who proved to be a rather unscrupulous but shrewd entrepreneur. Wolfson bought control (46.5% of outstanding shares) of Capital Transit for $2,189,160. After the lush war years, Capital Transit had amassed a bulging reserve of some $6 million, a tidy sum in that day.11 Running a viable transit system was not a high concern for Wolfson. Milking the company certainly was. His main objective was to relieve the company of its liquid assets, which he did quite efficiently, paying himself and his associates exorbitant dividends through 1955. As Wolfson diverted funds from operating necessities, service was cut and ridership predictably fell. Annual revenues declined commensurately. Moreover, his requests for fare increases were turned down by the DC Public Utility Commission, well aware of the generous dividends he was paying. Wolfson’s greed led to further service cuts and defiance in the face of not unreasonable wage demands 11 by the local transit union. A long, 55-day strike ensued, enraging the public and eventually Congress. Due to Wolfson’s inability or unwillingness to settle the strike, Congress stepped in and revoked Wolfson’s charter to operate the company. After a bumpy search for potential buyers, one was located and the company was sold in 1956 to an ebullient entrepreneur by the name of O. Roy Chalk. The new charter drawn up by Congress required Chalk to replace the streetcars with buses within a seven year period. Chalk unsuccessfully fought this provision. He even offered to establish a rapid streetcar service along Georgia Avenue at his own expense (which would have been a precursor to Washington’s Metro, built with government money).12 The streetcar system had received considerable rebuilding after the merger of 1935 and thus had significant economic life left. Moreover, the streetcars were profitable, serving the heaviest volume lines in the city. The operation was also completely equipped with modern PCC streetcars (named after the Presidents Conference Committee), many of which were only 12 years old when Chalk acquired the company. The fact that he was unsuccessful in removing this requirement is a testament to the forces arrayed against him and the streetcar, including the DC Department of Highways, 12 the national highway lobby and their Congressional allies, and, alas, The Washington Post. One cartoon in The Post pictured the Washington streetcar with the caption, “A Tough Dodo.” Motorists may not have liked Washington’s streetcars but they moved people efficiently, comfortably and profitably. They were popular with the transit-riding public. Predictably, when the streetcars were phased out, transit ridership in the District took a slow downward turn. To see why, one need look no further than Route 20, which ran from downtown Washington northwest along the Potomac River to Cabin John in suburban Maryland (serving the historic Glen Echo amusement park along the way). This route provided a comfortable, fast means for getting downtown. Blessed with a bucolic, reserved right of way from the Cabin John terminus to the (then) outskirts of Georgetown University, the streetcar was a popular way to access work, shopping and entertainment activities. Once the streetcar line was abandoned in early January, 1960 as Mr. Chalk grudgingly complied with the Congressional edict, anecdotal evidence indicates that residents along the line either added a second car or bought an automobile for the first time. The replacement bus line was no match for the speed, 13 comfort and neighborhood binding characteristics of the streetcar. Washington’s streetcar and bus ridership declined from 177.2 million passengers in 1957 (the last year before the streetcar abandonments commenced in full force) to 144.5 million passengers carried by an all-bus system in 1962, a decrease of some 18%.13 Subsequent declines were even steeper and ridership cratered after the 1968 riots that followed the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. With the final abandonment of streetcars in Washington on January 28, 1962, the nation’s capital became an all-bus city. It remained so until the advent of Metro’s first rail operating segment in 1976. The Act Today The Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 was repealed in 2005 and replaced with the Energy Policy Act, parts of which are sometimes referred to as PUHCA 2005. Where does that leave utilities that might want to invest in electric railways? Our research indicates that the answer is ambiguous. Some people think PUHCA 2005 imposes essentially no restrictions on public utility holding companies. Bill Lhota, President/CEO of the Central Ohio Transit Authority, writes: 14 With the repeal of the (1935 Public) Utility Holding Act, utilities can do just about anything they want to. It would have to make business sense but if AEP (American Electric Power) wanted to purchase or start a transit company, they are permitted to do so. They would have to set it up as a subsidiary of the parent holding company. There are laws that would prohibit direct cross subsidization from a regulated utility but as long as the dividends are paid up to the holding company, the holding company could use the funds as they see fit.14 That seems simple and straightforward. But as is usually the case with laws and government regulations, the devil is in the details. While PUHCA 1935 was repealed, the rules and regulations stemming from it were not. PUHCA 2005 transferred oversight over utility holding companies from the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). According to a 2006 study by the Congressional Research Service, FERC also determined that Section 1275(c) of the Energy Policy Act . . . was a “savings clause” which did not give the Commission the authority to issue regulations on previously regulated activities. As a result, FERC declined to issue further regulations on holding company system cross-subsidization, encumbrances of utility assets, [or] diversification into non-utility businesses . . .15 15 Many of the negative effects on electric railways that stemmed from the 1935 Act were not the result of legislative language but of subsequent court and regulatory rulings. Does this “savings clause” leave some of the rulings or regulations in effect, with the FERC unable, in its own view, to modify or repeal them? The answer is unclear. In a February, 2006 analysis of the then-new Energy Policy Act, the law firm of Winston & Strawn wrote, While investors can take advantage . . . of the EPAct 2005 and related rulemaking in structuring new transactions, the regulatory scheme remains complex, and there are traps for the unwary.16 A major potential trap lies in the prohibition of crosssubsidization by utilities of non-utility associates, a provision of PUHCA 1935 that was carried over in PUHCA 2005. That prohibition was what killed many utilityowned electric railways in the 1930s. To a layman, defining cross-subsidization seems simple: the utility is not allowed to give money to an associated electric railway to make up operating deficits, as many utility holding companies were doing before the 1935 Act. In fact, what the 2005 Act comprehends as cross-subsidization is much broader, to the point where it 16 could inhibit utilities from getting back into the electric railway business. The same Winston & Strawn brief notes that under PUHCA 2005, FERC must determine whether proposed transactions will result in cross-subsidies of non-utility associate companies, or pledges or encumbrances of utility assets and, if so, whether the cross-subsidy or pledge or encumbrance is consistent with the public interest.17 Whenever a regulatory body is given authority to act on the basis of “the public interest,” rulings become unpredictable. A 2008 FERC press release quoted FERC Chairman Joseph T. Kelliher as saying, Since Congress expanded our merger and corporate review authority (in the 2005 Act) we have sought to discharge our statutory duty to prevent the accumulation and exercise of market power and guard against improper cross-subsidization, . . .18 What might be ruled “improper” cross-subsidization? Our analysis suggests it might include providing capital funds from the utility to help construct an electric railway. The Winston & Strawn brief states, With respect to intra-holding company finances and cash management programs, FERC requires 17 applicants to adopt safeguards, including any cash management controls (such as restrictions on upstream transfers of funds, ring fencing, etc.) to prevent any cross-subsidization between holding companies and their new subsidiaries.19 Could providing capital up-front to build an electric railway be ruled an upstream transfer of funds within an intra-holding company financing? Maybe. PUHCA 2005 opened another can of legal worms at the state level. A 2006 brief on the new Act by the law firm Mayer Brown notes that PUHCA 2005 also provides [state] PUCs with access to the books and records of holding companies, but only to the extent relevant to the costs of subsidiaries that are public utilities. Many industry observers believe that PUCs may rush in to fill a perceived vacuum created by the repeal of PUHCA. These observers believe that PUCs will react to the loss of both extensive regulation of registered holding companies by the SEC and, equally important, the restrictions that exempt holding companies had to accept to maintain their exemptions . . . PUCs can be expected to much more aggressive in the search for potential crosssubsidization by utilities of non-utility affiliates.20 A long analysis of the post-2005 legal situation in the Lewis and Clark Law Review, “The Urge to Merge: A Look at the Repeal of the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935” by Nidhi Thakar, date August, 2008, updates this 18 issue and finds that states intend to use this loophole to full advantage. The article notes, As state commissions discover the regulatory gaps created by the repeal of PUHCA, we can expect states to . . . recreate the PUHCA regulatory model on a state level. State commissions have expressed concerns that, post-PUHCA, there is the potential for a variety of abuses by holding companies. Some of these abuses include utility company crosssubsidization of affiliate company transactions; . . . In response, many states have already enacted new statutes replacing regulatory oversight originally provided by PUHCA. California, Kansas, Maryland, Arkansas, and New Jersey are just a few of those states . . .Arkansas . . .enacted new statutes to prevent cross-subsidization between regulated public utilities and non-regulated affiliates that provide non-utility services. The rules prohibit utilities from providing or sharing financial resources, such as loans, extensions of credit, assumption of debt, and indemnification of affiliates, with unregulated utilities. Utilities are also restricted from incurring debt for any business other than regulated utility service in the state.21 What all this adds up to, as we suggested at the outset, is ambiguity. A utility’s legal department, if asked whether the company were in the clear to invest in an electric railway, might say, “We aren’t sure.” That could be enough to kill the investment. As conservatives, we have a problem with that. We want electric railways to be able to draw on every possible source of private financing. 19 The Private Funding Option Unlike bus lines, streetcar and light rail lines (and prospectively interurbans too) can attract private capital. The reason is simple. Electric railways raise property values in the areas they serve. Bus service has no such effect. The ability of streetcars to spur development can be observed in Washington, DC. One of the central components of developing the H Street, NE corridor in that city is a streetcar line (now in the final throes of construction). Developer after developer has cited the coming streetcar line as one of the reasons they decided to invest in the corridor. The same phenomenon is evident along the route of the proposed Cincinnati streetcar. In Portland, Oregon, where the streetcar renaissance began, almost $3 billion in development (within three blocks of the line) can be attributed to the presence of the Portland Streetcar (now carrying over 12,000 patrons each weekday). A recent study released by the Washington, DC Department of Planning found that the proposed 37 mile streetcar system for the District would generate between $10 $15 billion in benefits (new development, increased property tax collections on more valuable land, etc.).22 20 Property owners know this, and they are often willing to help pay for the line that will benefit them. Businesses along the streetcar or light rail line also benefit, because they get more customers. They, too, can be a source of private funding. This isn’t just theory. It is already happening. Take, for example, the 1.3 mile South Lake Union streetcar line in Seattle, WA, opened in 2007 at a cost of $47.5 million. Private investment was critical in securing the funding for the line. Property owners adjacent to the line created a Local Improvement District (LID). Through this device, property owners successfully raised $25 million of the cost, more than half.23 It proved to be money well spent. The streetcar has spurred $2.4 billion in private investment within roughly three blocks of the line, and created 12,000 permanent jobs. Private enterprise can also help provide operating funds for new electric rail lines. The Seattle streetcar receives some proceeds from the bulk purchase of transit passes by private companies and from the sale of streetcar sponsorships (naming rights for vehicles and stations) and uses them to help defray operating expenses. The Tampa Electric Company (TECO) streetcar receives its operating funds from a private endowment set up for this express purpose. Funds for the endowment were raised from the sale of naming rights for the system, the stations and the streetcars. At present, the yield from the 21 endowment is down dramatically, reflecting the state of the economy. The drop necessitated a reduction in operating hours (and a regrettable but unavoidable use of a portion of the endowment principal). Nevertheless, the concept is a good one. An endowment or similar instrument can fund all or a portion of a system’s operating cost. Another source of private funding for streetcar, light rail and interurban lines might be the same people who invested in them during the first trolley era: real estate developers. Many cities’ present shape - - including that of Los Angeles, the nation’s car capital - - is what it is because real estate developers built electric railways from the downtown to vast undeveloped tracts which they owned. Sometimes the electric railway made them money, and sometimes it didn’t (usually it did). But they made fortunes by developing real estate the streetcar or interurban served. Today, real estate developers get government to build roads to serve their new developments. As conservatives, we like the idea of developers paying for that service themselves rather than handing the bill to the taxpayers. In an era of rising gas prices and increasing traffic congestion, a developer who is smart enough to go back to the future and offer prospective homeowners electric rail service might make a handsome profit from higher prices on his houses. 22 This brings us back to the subject of our paper: the relationship between electric railways and electric power companies. We think electric utilities could again be a source for funds for building and possibly for operating electric railways -- if the remains of the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 were not stopping them. The tip of the iceberg is already showing. Duke Energy, the supplier of electric power to the city of Cincinnati, Ohio, has contributed about $3 million to the capital cost of Cincinnati’s planned streetcar line. Duke Power’s motive appears to have been helping to secure a rate increase, but it is still a signpost pointing to a possible future.24 Another signpost comes from a study done for the Central Ohio Transit Authority (COTA), which runs the transit system (now all-bus) in Columbus, Ohio. The study, done in 2009, states: In January 2009, William J. Lhota, President/CEO of the Central Ohio Transit Authority, created the Fixed Guideway Electrical Systems Study Committee (Committee) for the purpose of studying the feasibility of investor owned utilities owning, operating and maintaining the electrical systems used to power fixed guideway transit facilities. . . The Committee concludes that it is possible for investor owned utilities to own, operate and maintain 23 the electrical systems used to power fixed guideway transit facilities; . . .25 The Committee concludes that the public-private partnership studied by the Committee is an incredibly novel idea that is quite possible.26 In fact, the idea is not quite so incredibly novel as the Committee thinks. In New Orleans, America’s oldest rail transit line, the St. Charles Avenue line (which dates back to 1835) does something similar. New Orleans Public Service, Inc. (NOPSI), the local electric utility, now known as Entergy New Orleans, maintains the overhead and manages the power distribution system for the St. Charles line (and its venerable Perley Thomas streetcars built in 1923) as well as New Orleans’ other two streetcar lines, Canal and Riverfront. Obviously, if electric utilities are to get back into the electric railway business, they would do so with the expectation of making money (Entergy New Orleans does make money off of its contract with New Orleans’ Regional Transit Authority, owner and operator of the three streetcar lines). Bill Lhota of COTA recently wrote to the American Public Transportation Association (APTA): I think the profit motive will make transit opportunities viable for investor owned utilities. But, to assist transit companies, changes should be made in the law to allow utilities to sell tax exempt bonds for transit projects, not to pay sales tax on 24 purchases for transit projects, permit utilities to receive Federal Transit Administration grants and other incentives that make it more attractive for electric utilities to own, construct, operate and maintain electric infrastructure.27 Other measures that could entice electric utilities back into the electric railway business include: o As conservatives, we are against carbon emission taxes. But utilities could be given “green” tax credits for building and operating electric transit lines, which reduce pollution from automobiles. Such credits would make even more sense if the electricity for the transit line came from renewable resources - - as it already does in Calgary, Canada, where all the power for the city’s light rail system comes from wind turbines. o In return for capital cost contributions from utilities, offer long-term contracts to provide electricity for streetcar and light rail operations. o Tie other city government power contracts to helping pay for the electric rail system. In most places, customers can choose among power suppliers, and city governments are customers. 25 That, in fact, is the main reason electric power companies would want to get back into the electric railway business: to sell more electricity. That is how they make their money. However, so long as the ghost of the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 hovers over the scene, no electric power company is likely to get back into the electric railway business. What utility’s board of directors would dare vote to do so when their legal department tells them they might be subject to legal or regulatory action? So we conclude this paper with a conservative plea: will Congress please remove this roadblock dating back almost seventy-five years and let power companies back into the electric railway business? It costs nothing to do so. All it takes is a bit of legislative language. For that zero-cost input, we might be able to save the taxpayer hundreds of millions of dollars, even billions over time. What could be more conservative, or just common-sensical, than that? 26 Selected References Bloom, David I. “Repeal of the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 – Will the States Rush In?” Mayer Brown Publications, January, 2006. District of Columbia Office of Planning. Streetcar Land Use Study- Phase One. Washington, DC: January, 2012. Accessed at:http://planning.dc.gov/DC/Planning/Planning%20Publication %20Files/OP/Citywide/citywide_pdfs/FINAL%20for%20Web_Scr een%20View.pdf Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Fact Sheet: Energy Policy Act of 2005. August 8, 2006. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Federal Energy Commission News: FERC Acts to Strengthen Cross-Subsidization Rules. Washington: Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, February 21, 2008. Fixed Guideway Electrical Systems Study Committee. Final Report: Public-Private Partnerships. Central Ohio Transit Authority, July, 2009. Fogelson, Robert M. Downtown: Its Rise and Fall, 1880-1950. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001. Goddard, Stephen B. Getting There: The Epic Struggle Between Road and Rail in the American Century. New York: Basic Books, 1994. Hilton, George W., and Due, John F. The Electric Interurban Railways in America. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1960. Jones, David W. Mass Motorization + Mass Transit. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008. 27 Kohler, Peter C. Capital Transit: Washington’s Street Cars: The Final Era: 1933 – 1962. Colesville, MD: National Capital Trolley Museum, 2001. Marsh, Charles F. “The Local Transportation Problem in the District of Columbia.” The Journal of Land & Public Utility Economics, Vol. 10, No. 3 (August, 1934), p. 277. McDonald, Forrest. Insull. Chicago: The Chicago University Press, 1962. Ostrander, E.D. “The Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935.” The Journal of Land & Public Utility Economics, Vol. 12, No.1 (February, 1936), pp. 49-59. Post, Robert C. Urban Mass Transit: The Life Story of a Technology. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2007. St. Clair, David J. The Motorization of American Cities. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1986. Thakar, Nidhi. “The Urge to Merge: A Look at the Repeal of the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935.” Lewis and Clark Law Review, August, 2008. Accessed at: http://law.lclark.edu/live/files/9522-lcb123art11thakar.pdf U. S. Energy Information Administration. Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935: 1935 – 1992. Washington, D.C. U.S. General Accounting Office. “Public Utility Company Holding Act: Opportunities to Strengthen SEC’s Administration of the Act.” Washington, DC: GAO-05-617, July 8, 2005. U.S. Supreme Court. “North American Co. v. Securities and Exchange Commission, 327 U.S. Code 686 (1946).” FindLaw for Legal Professionals. Accessed at http://caselaw.findlaw.com. 28 Vann, Adam. The Repeal of the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 (PUHCA) and Its Impact on Electric and Gas Utilities. CRS Report for Congress. Congressional Research Service- Library of Congress, November 20, 2006. Found at: http://wiki.umn.edu/pub/ESPM3241W/S11PolicyBriefTeamTwent yfour/CRS_Report_for_Congress.pdf Weyrich, Paul M., and Lind, William S. Moving Minds: Conservatives and Public Transportation. Oakland, CA: Reconnecting America and The Free Congress Foundation, 2009. Winston and Strawn, LLP. Briefing- Energy Practice. “FERC Regulation of Transactions after the Energy Policy Act of 2005.” February, 2006. Accessed at: http://www.winston.com/siteFiles/publications/PUHCA_Section2 03.pdf. Yago, Glenn. The Decline of Transit: Urban Transportation in German and U.S. Cities, 1900-1970. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1984. 29 Endnotes 1 Philips, Charles F. The Regulation of Public Utilities, Theory and Practice. Public Utility Reports, Inc.. Arlington, VA, 1993, p.239. 2 St. Clair, David J. The Motorization of American Cities. Praeger Publishers, New York, 1986, p.110. 3 Hirsch, Dr. Richard. Emergence of Electric Utilities in America.” From Smithsonian Institute Exhibit “Powering a Generation of Change. <www.americanhistory.si.edu/csr/powering/> 4 Op Cit, St. Clair, p. 111. 5 Lhota, William H., President/CEO, Central Ohio Transit Authority, e-mail to authors, June 7, 2011. 6 Op Cit, St. Clair, p. 8. 7 Post, Robert C. Urban Mass Transit: The Life Story of a Technology. Westport, CT, Greenwood Press, 2007, p.111. 8 Energy Information Administration. Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935: 1935 – 1992, Washington, DC, January, 1993, p. 11. 9 Marsh, Charles F., “The Local Transportation Problem in the District of Columbia,” The Journal of Land & Public Utility Economics, August, 1934, Vol. 10, No. 3, p. 277. 10 U. S. Supreme Court, “North American Co. v. Securities and Exchange Commission, 327 U.S. Code 686 (1946),” Findlaw For Legal Professionals. < http://caselaw.findlaw.com > 11 “Strike Against Wolfson,” Time Magazine, Monday, July 18, 1955. <www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,866517,00.html>. 12 This was predictably opposed by the DC Department of Highways. Kohler, Peter C., Capital Transit: Washington’s Streetcars: The Final Era: 1933 – 1962 (Colesville, MD, National Capital Trolley Museum, 2001) p. 165. 13 Ibid, Kohler, p. 417. 14 Lhota, William H., President/CEO, Central Ohio Transit Authority, e-mail to authors, August 9, 2011. 15 Vann, Adam. “CRS Report for Congress: The Repeal of the Public Utility Holding Act of 1935 (PUCHA) and its Impact on Electric and Gas Utilities.” Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service-Library of Congress, November 20, 2006, p. 6. <http://wiki.umn.edu/pub/ESPM3241W/S11PolicyBriefTeamTwentyfour/CRS_Report_for_Co ngress.pdf > 30 16 Winston and Strawn, LLP, “Briefing: Energy Practice- FERC Regulation of Transactions after the Energy Policy Act of 2005,” February, 2006, p.1. 17 Ibid, Winston and Strawn, LLP, p. 6. 18 Federal Energy Regulatory Commission News: FERC Acts to Strengthen Cross-Subsidization Rules,” Washington: Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, February 21, 2008. 19 Op Cit, Winston and Strawn, p. 7. 20 Bloom, David I., “Repeal of the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935- Will the States Rush In?” Mayer Brown Publications, January 2006. < http://www.mayerbrown.com/germany/article.asp?id=2552&nid=495 > 21 Thakar, Nidhi, “The Urge to Merge: A Look at the Repeal of The Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935,” Lewis and Clark Law Review, August 30, 2008, Vol. 12-3, pp.937938. < http://lawlclark.edu/live/files/9o522-lcb123art11thakar.pdf > 22 DC Office of Planning, “Streetcar Land Use Study- Phase One,” Washington, DC: January, 2012, p. 10. http://planning.dc.gov/DC/Planning/Planning%20Publication%20Files/OP/Citywide/citywide_ pdfs/FINAL%20for%20Web_Screen%20View.pdf> 23 City of Seattle, Office of Policy and Management, “South Lake Union Streetcar: Capital Financing and Operating and Maintenance Plan,” Seattle, WA: April 13, 2005. 24 Business Courier of Cincinnati, “Duke Energy to Help Finance Cincinnati Streetcar Initiative,” October 29, 2008. < http://bizjournals.com/cincinnati/stories/2008/10/27/daily32.html > 25 Fixed Guideway Electrical Systems Study Committee, “Final Report: Public-Private Partnerships,” Central Ohio Transit Authority (COTA), July, 2009, p. ii. 26 Ibid, Fixed Guideway Electrical Systems Study Committee, p. 6. 27 Lhota, William H., President/CEO, Central Ohio Transit Authority, e-mail to APTA, June 7, 2011. 31