Pro-Bomb

advertisement

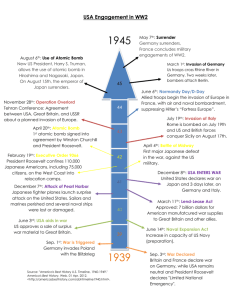

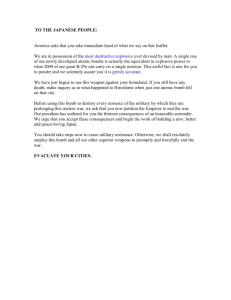

United States History: Pro-Use of Atomic Bomb BY BILL DIETRICH Seattle Times staff reporter Historians are still divided over whether it was necessary to drop the atomic bomb on Japan to end World War II. Here is a summary of arguments on both sides: Why the bomb was needed or justified: The Japanese had demonstrated near-fanatical resistance, fighting to almost the last man on Pacific islands, committing mass suicide on Saipan and unleashing kamikaze attacks at Okinawa. Fire bombing had killed 100,000 in Tokyo with no discernible political effect. Only the atomic bomb could jolt Japan's leadership to surrender. With only two bombs ready (and a third on the way by late August 1945) it was too risky to "waste" one in a demonstration over an unpopulated area. An invasion of Japan would have caused casualties on both sides that could easily have exceeded the toll at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The two targeted cities would have been firebombed anyway. Immediate use of the bomb convinced the world of its horror and prevented future use when nuclear stockpiles were far larger. The bomb's use impressed the Soviet Union and halted the war quickly enough that the USSR did not demand joint occupation of Japan. Why the bomb was not needed, or unjustified: Japan was ready to call it quits anyway. More than 60 of its cities had been destroyed by conventional bombing, the home islands were being blockaded by the American Navy, and the Soviet Union entered the war by attacking Japanese troops in Manchuria. American refusal to modify its "unconditional surrender" demand to allow the Japanese to keep their emperor needlessly prolonged Japan's resistance. A demonstration explosion over Tokyo harbor would have convinced Japan's leaders to quit without killing many people. Even if Hiroshima was necessary, the U.S. did not give enough time for word to filter out of its devastation before bombing Nagasaki. The bomb was used partly to justify the $2 billion spent on its development. The two cities were of limited military value. Civilians outnumbered troops in Hiroshima five or six to one. Japanese lives were sacrificed simply for power politics between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. Conventional firebombing would have caused as much significant damage without making the U.S. the first nation to use nuclear weapons. The Decision to Drop the Bomb For Truman, the choice whether or not to use the atomic bomb was the most difficult decision of his life. First, an Allied demand for an immediate unconditional surrender was made to the leadership in Japan. Although the demand stated that refusal would result in total destruction, no mention of any new weapons of mass destruction was made. The Japanese military command rejected the request for unconditional surrender, but there were indications that a conditional surrender was possible. Regardless, on August 6, 1945, a plane called the Enola Gay dropped an atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima. Truman stated that his decision to drop the bomb was purely military. A Normandy-type amphibious landing would have cost an estimated million casualties. Truman believed that the bombs saved Japanese lives as well. Prolonging the war was not an option for the President. Over 3,500 Japanese kamikaze raids had already wrought great destruction and loss of American lives. The President rejected a demonstration of the atomic bomb to the Japanese leadership. He knew there was no guarantee the Japanese would surrender if the test succeeded, and he felt that a failed demonstration would be worse than none at all. Even the scientific community failed to foresee the awful effects of radiation sickness. Truman saw little difference between atomic bombing Hiroshima and fire bombing Dresden or Tokyo. THE BIGGEST DECISION: WHY WE HAD TO DROP THE ATOMIC BOMB Rational calculations did not determine Japan’s position. Although a peace faction within the government wished to end the war—provided certain conditions were met—militants were prepared to fight on regardless of consequences. They claimed to welcome an invasion of the home islands, promising to inflict such hideous casualties that the United States would retreat from its announced policy of unconditional surrender. The militarists held effective power over the government and were capable of defying the emperor, as they had in the past, on the ground that his civilian advisers were misleading him. Okinawa provided a preview of what invasion of the home islands would entail. Since April 1 the Japanese had fought with a ferocity that mocked any notion that their will to resist was eroding. They had inflicted nearly 50,000 casualties on the invaders, many resulting from the first large-scale use of kamikazes. They also had dispatched the superbattleship Yamato on a suicide mission to Okinawa, where, after attacking American ships offshore, it was to plunge ashore to become a huge, doomed steel fortress. Yamato was sunk shortly after leaving port, but its mission symbolized Japan’s willingness to sacrifice everything in an apparently hopeless cause. In his memoirs Truman claimed that using atomic bombs prevented an invasion that would have cost 500,000 American lives. Other officials mentioned the same or even higher figures. Critics have assailed such statements as gross exaggerations designed to forestall scrutiny of Truman’s real motives. They have given wide publicity to a report prepared by the Joint War Plans Committee (JWPC) for the chiefs’ meeting with Truman. The committee estimated that the invasion of Kyushu, followed by that of Honshu, as the chiefs proposed, would cost approximately 40,000 dead, 150,000 wounded, and 3,500 missing in action for a total of 193,500 casualties.