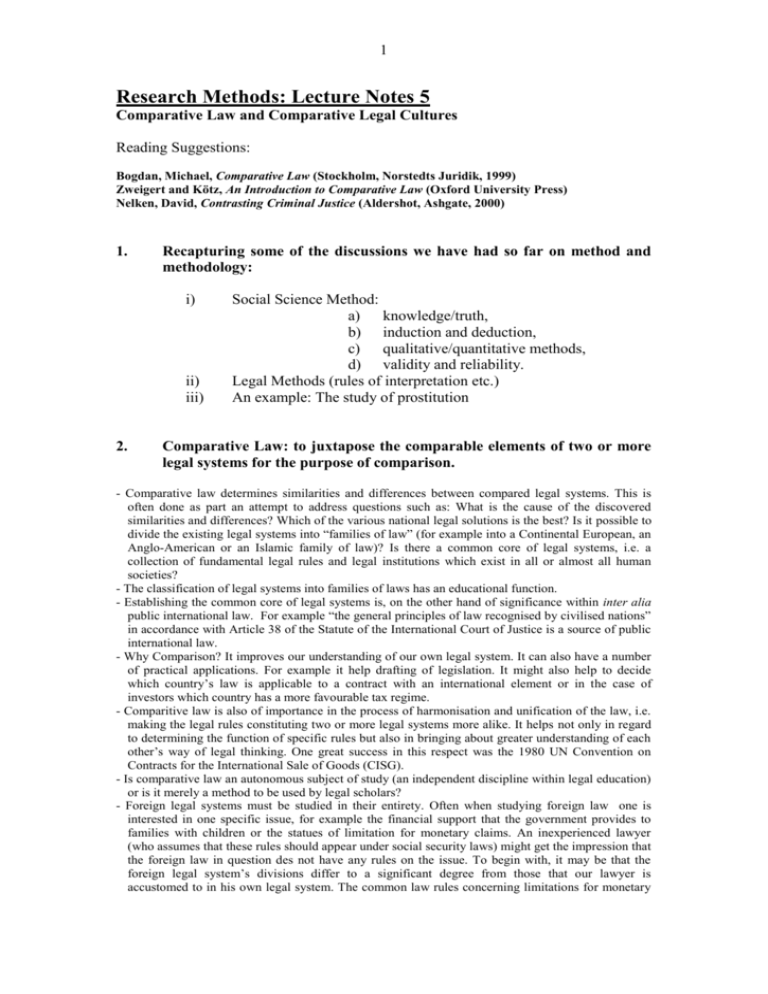

Research Methods: Lecture Notes 5

advertisement

1 Research Methods: Lecture Notes 5 Comparative Law and Comparative Legal Cultures Reading Suggestions: Bogdan, Michael, Comparative Law (Stockholm, Norstedts Juridik, 1999) Zweigert and Kötz, An Introduction to Comparative Law (Oxford University Press) Nelken, David, Contrasting Criminal Justice (Aldershot, Ashgate, 2000) 1. Recapturing some of the discussions we have had so far on method and methodology: i) ii) iii) 2. Social Science Method: a) knowledge/truth, b) induction and deduction, c) qualitative/quantitative methods, d) validity and reliability. Legal Methods (rules of interpretation etc.) An example: The study of prostitution Comparative Law: to juxtapose the comparable elements of two or more legal systems for the purpose of comparison. - Comparative law determines similarities and differences between compared legal systems. This is often done as part an attempt to address questions such as: What is the cause of the discovered similarities and differences? Which of the various national legal solutions is the best? Is it possible to divide the existing legal systems into “families of law” (for example into a Continental European, an Anglo-American or an Islamic family of law)? Is there a common core of legal systems, i.e. a collection of fundamental legal rules and legal institutions which exist in all or almost all human societies? - The classification of legal systems into families of laws has an educational function. - Establishing the common core of legal systems is, on the other hand of significance within inter alia public international law. For example “the general principles of law recognised by civilised nations” in accordance with Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice is a source of public international law. - Why Comparison? It improves our understanding of our own legal system. It can also have a number of practical applications. For example it help drafting of legislation. It might also help to decide which country’s law is applicable to a contract with an international element or in the case of investors which country has a more favourable tax regime. - Comparitive law is also of importance in the process of harmonisation and unification of the law, i.e. making the legal rules constituting two or more legal systems more alike. It helps not only in regard to determining the function of specific rules but also in bringing about greater understanding of each other’s way of legal thinking. One great success in this respect was the 1980 UN Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG). - Is comparative law an autonomous subject of study (an independent discipline within legal education) or is it merely a method to be used by legal scholars? - Foreign legal systems must be studied in their entirety. Often when studying foreign law one is interested in one specific issue, for example the financial support that the government provides to families with children or the statues of limitation for monetary claims. An inexperienced lawyer (who assumes that these rules should appear under social security laws) might get the impression that the foreign law in question des not have any rules on the issue. To begin with, it may be that the foreign legal system’s divisions differ to a significant degree from those that our lawyer is accustomed to in his own legal system. The common law rules concerning limitations for monetary 2 claims might (surprising as it might be to a Continental lawyer) appear in books and collections of judgements concerning procedural law. - Another fact that must not be disregarded is that a foreign law-maker, even in country with similar divisions , may have chosen another method to attain the same objective, and that this perhaps means that the relevant legal rules belong to another part of the legal system. If a Swedish lawyer is interested in the regulation of the society’s financial support to families with children in for instance France, he should not limit himself to looking into social security laws such as those used in Sweden (child allowance, housing etc.) since a substantial share of the governmental financial support provided to large families in France is not paid out in the form of social law subsidies but rather by means of the tax law and in the form of a considerably reduced tax obligation (a form of support that is not used in Sweden). - In a similar manner the rights of a surviving spouse to share in the division of property of the deceased spouse is in certain countries primarily based on inheritance law, while in other legal systems it is regulated in matrimonial law. - Hence, one must study the foreign legal system in its entirety even when one is only interested in a specific issue. 3. Comparative Legal Cultures See: Bogdan, Michael, Comparative Law (Stockholm, Norstedts Juridik, 1999) - - - - Comparative studies of law which focus exclusively on the rules of law (law on the books) tend to neglect the institutional aspects of the law (law in action). Internal and external legal cultures The internal legal cultures include the taken for granted values, principles, attitudes and standards of the judiciary The external legal culture include the attitude and expectations of ordinary men and women in respect to law and legal institutions Comparative law need to capture both the internal and the external legal cultures. To achieve this one needs to see the other (the foreign) legal culture/system from within and without. One needs distance and firsthand experience of the foreign culture one is studying. Firsthand experience helps her understand what the practioners of the law in that legal system are doing (what sort of meaning they attach their actions). The distance helps the researcher to sustain a “neutral” position in respect to its object of study. The comparativist also requires a similar awareness in regard to his/her own legal cultural values, principles, methods and standards. Both these assume the mastery of another language, general culture, law, legal practice (these place comparative studies in a cultural context). One needs to locate comparable data. How do we select relevant material? We can use interviews (see below for their shortcomings) and participant observation. In certain cases quantitative data can provide important insights. The Comparativist as Participant Observer Jacqueline Hodges (see Nelken 2000) has investigated the working practices of those involved in the investigation and prosecution of crime in France. Hodges argues that “comparativists (whether or not conducting empirical work) is engaging in a form of legal anthropology and is a participant observer. She is attempting to permeate another culture, at the every least to understand its institutional structures, laws and procedures, but hopefully also its language, customs, ideologies, legal cultures and practices. The interpretation of her findings, and indeed the search itself, are influenced by her own legal cultural perspective and the way in which she gathers and reports information.” (p. 139). She starts her research by studying the earlier accounts and comparisons of the French criminal justice process. She discovers few systematic frameworks for a systematic approach to the study of foreign legal systems in general and to the study of criminal justice process in particular. 3 - - Instead she finds a range of studies paying more or less attention to theory, method and coverage. Many studies are formal descriptions of institutions, rules and processes. They provide no insight into the daily practices within the legal system. Formalist accounts are reductionist and decontextualised. How do we select relevant material? Even interviews might not produce reliable empirical data which does not reflect daily routines and experiences. The problems associated with decontextualisation are not resolved by interviewing the functionaries of the law, who might offer us “presentational data which does not reflect the daily routines and experiences”. The data collected through interviews need to be tested through participant observation. In conclusion, Hodgson maintains that it is when the researcher uses ethnography to immerse herself in the field that she can identify important and relevant issues and bring us closer to resolving many of the problems sketched above. However, Hodgson tends to exaggerate the potential of ethnography, which neither is always possible to adopt, nor necessarily the best way of doing research. Prosecutor Culture in Japan This study which is by David Johnson aims “to display and analyse the different assumptions and intentions the Japanese bring to public life, compared to the Americans, and to uncover the likely consequences of these Japanese orientations” (see Nelken 2000, p. 157). - For Johnson Legal culture in “internal legal culture”. He interviews 235 Japanese prosecutor and collect information about their background and their reasons for choosing a career as a prosecutor. His main objective is to investigate why prosecutors in Japan so often go out of their way not to charge suspects. He thus questions the general assumption that prosecutors have universal aims such as the desire to maximise conviction (such assumptions are based on alleged prosecution practices in the USA which are not even true there). This study consists of a large-scale application of survey and interview methods to a comparative examination of the Japanese and American prosecutors’ legal cultures. In contrast to Hodgson, Johnson departs unperturbedly from an “internal” definition of legal culture and employs a positivistic methodology to carry out his investigation. He seems to be doing all that Hodgson just warned us against. One might well find many of Hodgson’s arguments convincing, yet reading through Johnson’s study one cannot help recognising that many of the interesting findings presented by him are precisely due to his application of the positivistic methods of investigation, which were discarded by Hodgson. It is true that Johnson could not know if what the prosecutors told him were but “presentational data”. Yet, had he not applied surveys, he could not with any degree of certainty establish the frequency in which prosecution was suspended or that women prosecutors in Japan were assigned trivial cases. One cannot help asking who is right then Hodgson or Johnson?