技 能 教 学 (一) - 长沙民政职业技术学院

advertisement

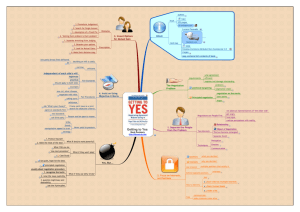

长沙民政职业技术学院应用外语系 技 能 教 学 (一) ※<WEEK--2> 1. Do you know when you shouldn’t negotiate? There are times when you should avoid negotiate. In these situations, stand your ground and you’ll come out ahead. 1.1 When you’d lose the farm 1.2 When you are sold out When you are running at capacity, don’t deal. Raise your prices instead. 1.3 When the demands are unethical Don’t negotiate if your counterpart asks for something that you cannot support because it’s illegal, unethical, or morally inappropriate. When your character or your reputation is compromised, you lose in the long run. 1.4 When you don’t care If you have no stake in the outcome, don’t negotiate. You have everything to lose and nothing to gain. 1.5 When you don’t have time If the time pressure works against you, you’ll make mistakes, and you may fail to consider the implications of your concessions. When under the gun, you’ll settle for less than you could otherwise get. 1.6 When they act in bad faith 长沙民政职业技术学院应用外语系 Stop the negotiation when your counterpart shows signs of acting in bad faith. If you can’t trust their negotiating, you can’t trust their agreement. Stick to your guns and cover your position, or discredit them. 1.7 When waiting would improve your position Perhaps you’ll have a new technology available soon. Maybe your financial situation will improve. Another opportunity may present itself. If the odds are good that you’ll gain ground with a delay, wait. 1.8 When you’re not prepared 2. The Planning Process 2.1 Effective planning also requires hard work on the following several fronts: a. Defining the issues – What are the issues in the upcoming negotiation? b. Assembling the issues and defining the bargaining mix – Which issues do we have to cover? Which issues are connected to other issues? c. Defining interests – What are my interests? d. Defining limits – What is my walkaway? What is my alternative? e. Defining one’s objectives (targets) and opening bids (where to start?) – where shall start and what is my goal? f. Defining the constituents to whom one is accountable – Who are my constituents and what do they want me to do? 长沙民政职业技术学院应用外语系 g. Understanding the other party and its interests and objectives – What are the opposing negotiators and what do they want? h. Selecting a strategy – What overall strategy do I want to select? i. Planning the issue presentation and defense – How will I present my issues to the other party? j. Defining protocol – where and when the negotiation will occur, who will be there, agenda, etc. 3. How will I present the issues to the other party? One important aspect of actual negotiations is to present a case clearly and to martial ample supporting facts and arguments; another is to refute the other party’s arguments with counterarguments. The following guides can be used to assemble information: a. What facts support my points of view? What substantiates and validates this information as factual? b. Whom may I consult or talk with to help me elaborate or clarify the facts? What records, files, or data sources exist that support my arguments? c. Have these issues been negotiated before by others under similar circumstances? Can consult those negotiators to determine what major arguments they used, which ones were successful and which ones were not? d. What is the other party’s point of view likely to be? What are 长沙民政职业技术学院应用外语系 his or her interests? What arguments is the other party likely to make? How can I respond to those arguments and seek more creative positions that go further in addressing both side’s issues and interests? e. How can I develop and present the facts so they are most convincing? What visual aids, pictures, charts, graphs, expert testimony, and the like can be helpful or make the best case? 长沙民政职业技术学院应用外语系 ※<WEEK--3> 1. Salary Negotiation Tips: Myron Lieschutz offers 8 tips for success when job applicants must negotiate a salary package with a prospective employer: a. Delay discussion of compensation until after you have been offered the job. b. After the employer presents the offer and quotes the salary range, remain silent for about 30 seconds. By remaining quiet, you invite the other person to mention a higher figure or talk about flexibility. Then negotiation can begin. c. Don’t comment on the salary offer immediately. Instead, clarify some other aspects the job’s responsibilities and reaffirm where and how you believe you can benefit the organization. d. The say the offer is a bit on the conservative side, though the position is still very attractive. Say you would like to think it over and talk again the next day. e. Don’t discuss benefits before salary. Get agreement on salary first, then negotiate the fringe benefits. f. Be aware of over-negotiating. Ask for too much, even if you get it, may cause you to be viewed with resentment and can hinder you in the future salary reviews. 长沙民政职业技术学院应用外语系 g. Whatever the offer, do not accept it on the spot. Express interest, but again ask for a day to think it over. The job won’t go away, and the employer may come up with a better offer given some additional time to get approval. h. If the company cannot meet your annual salary requirements, look for other options such as a one-time, up-front bonus, extended vacation, or specific monetary rewards for performance goals. 2. Closing the deal Choosing the best tactic for a given negotiation is as much a matter of art as science: a. Provide alternatives. Rather than making a single final offer, negotiators can provide two or three alternative packages for the other party that are more or less equivalent in value. People like to have choices, and providing a counterpart with alternative packages can be a very effective technique for closing a negotiation. b. Assume the close. Salespeople use an assume-the-close technique frequently. After having a general discussion about the needs and positions of the buyer, often the seller will take out a large order form and start to complete it. They act as if the decision to purchase sth has already been made so they might as well start to get the paperwork out of the way. 长沙民政职业技术学院应用外语系 c. Split the difference. Splitting the difference is perhaps the most popular closing tactic. The negotiator using this tactic will typically give a brief summary of the negotiation and then suggest that, because things are so close, “why don’t we just split the difference?” d. Exploding offers. An exploding offer contains an extremely tight deadline in order to pressure the other party to agree quickly. For example, a person who has interviewed for a job may be offered a very attractive salary and benefits package, but also be told that the offer will expire in 24 hours. The purpose of the exploding offer is to convince the other party to accept the settlement and to stop considering alternatives. 3. What makes integrative negotiation different? 3.1 For a negotiation to be characterized as integrative, negotiators must also: a. Focus on commonalities rather than differences b. Attempt to address needs and interests, not positions c. Commit to meeting the needs of all involved parties d. Exchange ideas and information e. Invent options for mutual gain f. Use objective criteria for standards of performance These requisite behaviors and perspectives are the main components of the integrative process. 长沙民政职业技术学院应用外语系 3.2 Characteristics of the interest-based negotiator A successful interest-based negotiator models the following traits: a. Honesty and integrity. Interest-based negotiation requires a certain level of trust between the parties. Actions that demonstrate interest in all players’ concerns will help establish a trusting environment. b. Abundance mentality. Those with an abundance mentality do not perceive a concession of monies, prestige, control, and so on, as something that makes their slice of the pie smaller, but merely as a way to enlarge the pie. A scarcity or zero-sum mentality says, “Anything I give to you takes away from me”. A negotiator with abundance mentality knows that making concessions helps build stronger long-term relationships. c. Maturity. In his book Seven Habits of Highly Effective Leaders, Stephen Covey refers to maturity as having the courage to stand up for your issues and values while being able to recognize that other’s issues and values are just as valid. d. Systems orientation. System thinkers will look at ways in which the entire system can be optimized, rather than focusing on sub-optimizing components of the system. e. Superior listening skills. Ninety percent of communication is not in one’s words but in the whole context of the communication, including mode of expression, body language, and many other cues. 长沙民政职业技术学院应用外语系 Effective listening also requires that one avoid listening only from his or her frame of reference. 3.3 An overview of the integrative negotiation process a. Creating a free flow of information b. Attempting to understand the other negotiator’s real needs and objectives c. Emphasizing the commonalities between the parties and minimizing the differences d. Searching for solutions that meet the goals and objectives of both sides 3.4 Key steps in the integrative negotiation process a. Identify and define problem b. Define the problem in a way that is mutually acceptable to both sides c. State the problem with an eye toward practicality and comprehensiveness d. State the problem as a goal and identify the obstacles to attempting this goal e. Depersonalize the problem – saying “Your point of view is wrong and mine is right” inhibits the integrative negotiation process because you cannot attack the problem without attacking the person who owns the problem. In the contrast, depersonalizing the definition of the problem – stating, for example, “We have different viewpoints on this 长沙民政职业技术学院应用外语系 problem” – allows both sides to approach the issue as a problem “out there’ rather than as a problem that belongs to one side only. f. Separate the problem definition from the search for solution g. Understand the problem fully – Identify interests and needs h. Generate alternative solutions: Expand the pie; Logroll – Successful logrolling requires the parties to establish (or find ) more than one issue in conflict; the parties then agree to trade off among these issues so that one party achieves a highly preferred outcome on the first issue and the other party achieves a highly preferred outcome on the second issue. If the parties do in fact have different preferences on different issues and each party gets his or her most preferred outcome on a high-priority issue, then each should be happy with the overall agreement; Use non-specific compensation –A third way to generate alternatives is to allow one person to obtain his objectives and pay off the other person for accommodating his interests. The payoff may be unrelated to the substantive negotiation. Cut the costs for compliance – Through cost cutting, one party achieves her objectives and the other’s costs are minimized if he agrees to go along. It is specifically designed to minimize the other party’s costs and suffering. Find a bridge solution – by “bridging”, the parties are able to invent new options that meet their respective needs. Successful bridging requires a fundamental reformulation of the problem such that the parties are no longer 长沙民政职业技术学院应用外语系 squabbling over their position; instead, they are disclosing sufficient information to discover their interests and needs and then inventing options that will satisfy those needs. 3.5 Refocusing questions to reveal win-win options l. Expand the pie a. How can both parties get what they want? b. Is there a resource shortage? c. How can resources be expanded to meet the demands of both parties? 2. Logrolling a. What issues are of higher and lower priority to me? b. What issues are of higher and lower priority to the other? c. Are there any issues of high priority to me that are of low priority for the other, and vice versa? d. Can I “unbundled” an issue –that is, make one larger issue into two or more smaller ones that can then be log rolled? e. What are things that would be inexpensive for me to give and valuable for the other to get that might be used in logrolling? 3. Non-specific compensation a. What are the other party’s goals and values? b. What could I do that would make the other side happy and simultaneously allow me to get my way on the key issues? 长沙民政职业技术学院应用外语系 c. What are things that would be inexpensive for me to give and valuable for the other to get that might be used as nonspecific compensation? 4. Cost cutting a. What risks and costs does my proposal create for the other? b. What can I do to minimize the other party’s risks and costs so that he or she would be more willing to agree? 5. Bridging a. What are the other’s real underlying interests and needs? b. What are my own real underlying interests and needs? c. What are the higher and lower priorities for each of us in our underlying interests and needs? d. Can we invent a solution that meets the relative priorities, underlying interests, and needs of both parties? 长沙民政职业技术学院应用外语系 ※<WEEK--4> The Skills to focus on Interests, Rights and Power in Negotiation Interests, Rights, and Power in Negotiation One way of thinking about the role of power in negotiation is in relation to other, alternative strategic options. In Chapter2 we introduced a framework developed by Ury, Brett, and Goldberg (1993) that compares three different strategic approaches to negotiation: interests, right, and power. Negotiators focus on interests when they strive to learn about each other’s interests and priorities as a way to work toward a mutually satisfying agreement that creates value. Negotiators focus on rights when they seek to resolve a dispute by drawing upon decision rules or standards grounded in principles of law, fairness, or perhaps and existing contract. Negotiators focus on power when they use threats or other means to try to coerce the other party into making concessions. This framework assumes that all three approaches can potentially exist in a single situation; negotiators make choices about where to place their focus. But do negotiators really use all three? Should they? These questions were addressed in a study by Anne Lytle, Jeanne Brett, and Debra Shapiro (1990). They analyzed audiotapes of negotiations of a simulated contract dispute between two companies seeking to clarify their 长沙民政职业技术学院应用外语系 interdependent business relationship. Of the 50 negotiators who participated (25 tape-recorded pairs), some were students and some were employed managers, but all had five or more years of business experience. Lytle and her colleagues found that most negotiators cycled through all three strategies—interests, rights, and power—during the same encounter, They also found that negotiators tended to reciprocate these strategies. A coercive power strategy, for example, may be met with a power strategy in return, which can lead to a negative conflict spiral and a poor (or no) agreement. They developed some important implications for the use of power in negotiation: Starting a negotiation by conveying your own power to coerce the other party could bring a quick settlement if your threat is credible. If the other party calls your bluff, however, you are left to either carry out your threat or lose face, both of which may be undesirable. To avert a conflict spiral and move toward an interests-based exchange, avoid reciprocating messages involving rights or power. Shift the conversation by asking an interests-related question. I may take several attempts to redirect the interaction successfully. If you can’t avoid reciprocating negative behaviors (which is , after all, only natural),try a “combined statement” that mixes a threat with an interests-oriented refocusing question or statement (e.g. , “yes, we 长沙民政职业技术学院应用外语系 could sue you as well, but that won’t solve our problem, so why don’t we try to reach an outcome that helps us both?”). Power tactics (and rights tactics) may be most useful when the other party refuses to negotiate or when negotiations have broken down and need to be restarted. In these situations, not much is risked by making threats based on rights or power, but the threat itself may help the other party appreciate the severity of the situation. The success of power tactics (and rights tactics) depends to a great extent on how they are implemented. To be effective, threats must be specific and credible, targeting the other party’s high-priority interests. Otherwise, the other party has little incentive to comply. Make sure that you leave an avenue for the other party to “turn off “ the threat, save face, and reopen the negotiations around interests. After all, most negotiators who make threats really don’t want to implement the. As Lytle et al. observe, “once you carry through with your threat, you frequently lose your source of power” (p.48). 长沙民政职业技术学院应用外语系 ※<WEEK--5> How to defend ourselves when receiving offensive comments? When you are on the receiving end of offensive comments in a negotiation setting, your first response may be to offend back, or to stalk off in anger and displeasure. For important negotiations, though, this creates the risk of denying you (as well as the other parties) any mutual gains from the exchange, as well as diverting your attention from the issues that brought you to the table in the first place. Andrea Schneider (1994) suggests that your basic options when occurred and then deciding what to do about it, to understanding the behavior, she suggests for steps: ● Check your assumptions. ● Check the data on which your assumptions are based. ● Seek and evaluate other data, even (or especially) if those data tend to disconfirm your assumptions. ● Evaluate and adjust your assumptions, as appropriate, Once your assumptions seem correct and appropriate, and then decide whether to handle the behavior by ● Ignoring it (just act like it never occurred). ● Confronting it (i.e. counterattack: “that’s racist,” or “how juvenile”) ● Deflecting it (i.e. acknowledge it and move on--- a sense of humor often helps here). 长沙民政职业技术学院应用外语系 ● Engaging it (talk with the other party about his or her purpose in being offensive and about your reaction to the offense). 长沙民政职业技术学院应用外语系 ※<WEEK--6> Three Rules for Negotiating a Relationship International negotiation expect Jeswald Salacuse (1998) suggests three important rules for negotiating a relationship Don’t rush pre-negotiation. Spend ample time getting to know the other party, visiting with him, learning about him, and spending time with him. This process enhances your information gathering and builds a relationship that may include trust, information sharing, and productive discussions. I particular, North American executives have a tendency to rush through things in order to get down to business, which compromises this critical stage for relationship building. Recognize a long-term business deal as a continuing negotiation. Change and uncertainty are constants in any business deal. The discussions so not end when the contract is signed; the discussion continue as the parties perform according to the contract, and often have to meet to work out problems and renegotiate specific parts of the agreement. Consider mediation or conciliation. Finally, consider the roles that can usefully be played by third parties. A third party can help monitor the deal, work out disagreements about contract violations, and assure that the agreement does not go sour because the parties cannot resolve differences in interpretation or enforcement.