Stinson Sample Motion #1 - Cleveland

advertisement

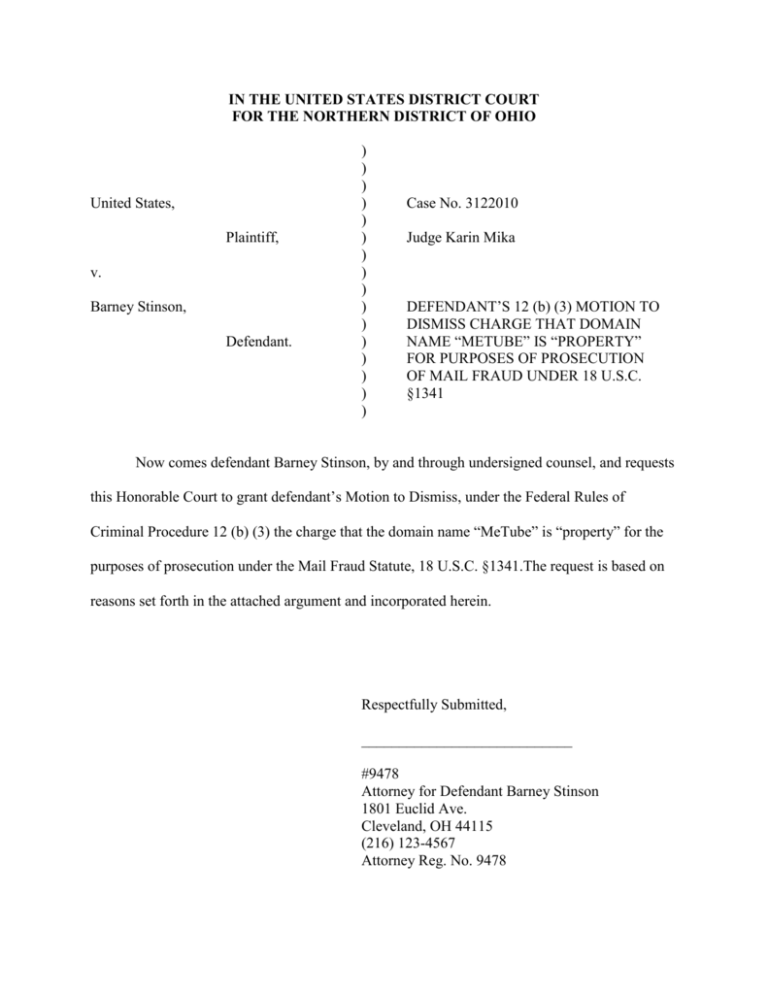

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF OHIO United States, Plaintiff, v. Barney Stinson, Defendant. ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) Case No. 3122010 Judge Karin Mika DEFENDANT’S 12 (b) (3) MOTION TO DISMISS CHARGE THAT DOMAIN NAME “METUBE” IS “PROPERTY” FOR PURPOSES OF PROSECUTION OF MAIL FRAUD UNDER 18 U.S.C. §1341 Now comes defendant Barney Stinson, by and through undersigned counsel, and requests this Honorable Court to grant defendant’s Motion to Dismiss, under the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure 12 (b) (3) the charge that the domain name “MeTube” is “property” for the purposes of prosecution under the Mail Fraud Statute, 18 U.S.C. §1341.The request is based on reasons set forth in the attached argument and incorporated herein. Respectfully Submitted, ____________________________ #9478 Attorney for Defendant Barney Stinson 1801 Euclid Ave. Cleveland, OH 44115 (216) 123-4567 Attorney Reg. No. 9478 STATEMENT OF THE FACTS The facts of this case involve the defendant Barney Stinson who is being charged with mail fraud in violation of 18 U.S.C. §1341, despite the fact that all the elements of the statute have not been met. Mr. Stinson acquired a domain name, “MeTube,” from the registrar Reg-Dot-Co. The company claimed to be using the name regardless of the undisputed fact that they had absolutely no documentation, official or unofficial, to support this alleged ownership. Reg-Dot-Co merely “squatted” on what they believed might be popular domain names someday, and sold these names to consumers who wanted the names registered for their own productive use. Furthermore, the company did not pay any money whatsoever for the domain names, nor was there any factual indication that they were the only company or entity “using” the names at any given time. This argument is submitted to the court in support of defendant Stinson’s motion requesting the charge in violation of 18 U.S.C. §1341 be dismissed on the basis that the domain name “MeTube” is not “property” for purposes of prosecution under the Mail Fraud Statute. ARGUMENT THE DOMAIN NAME “METUBE” IS NOT PROPERTY FOR PURPOSES OF PROSECUTION OF MAIL FRAUD UNDER 18 U.S.C. §1341 WHEN THE COMPANY USING THE DOMAIN NAME BEFORE THE DEFENDANT CANNOT CLAIM ANY VALUE IN THE NAME NOR ASSERT EXCLUSIVE TRANSFERABLE USE OVER IT. 18 U.S.C. §1341, the Mail Fraud Statute, states, “whoever, having devised…any scheme or artifice to defraud… for [the purpose of] obtaining…property by means of false or fraudulent pretenses…places in any post office…anything whatever to be sent or delivered by the Postal Service…shall be fined under this title or imprisoned…” [Emphasis added.] At issue here is the definition of the term “property.” “Property” may include “every [tangible and] intangible benefit” subject to possession. Kremen v. Cohen, 337 F.3d 1024, 1029 (9th Cir. 2003). “Intangible benefits” are construed as those without a physical existence. G.S. Rasmussen v. Kalitta, 958 F.2d 896, 903 (9th Cir. 1992). But see McNally v. United States, 484 U.S. 350, 356 (1987) (limiting the scope of 18 U.S.C. §1341 by not considering an “intangible right to honest government” as property). However, these broad definitions of property at the common law are narrowed for the purposes of prosecution under the Mail Fraud Statute. Here, in determining what constitutes “property,” the court looks at only three specific elements. These are value, exclusivity, and transferability. 337 F.3d at 1029. A defendant will not be convicted of Mail Fraud unless these three elements are met. In Stinson’s case, “MeTube” is not property under the Mail Fraud Statute, because Reg-Dot-Co’s use of the name prior to Stinson’s letter fails to satisfy the three elements of property laid out by the law. Firstly, Reg-Dot-Co can claim no value in “MeTube” prior to a sale because of the fact that they are simply “squatting” on it. Furthermore, nothing in the undisputed facts indicates that Reg-Dot-Co has any basis for asserting exclusive and transferable ownership over “MeTube.” On the contrary, the company does not have any documentation or authority upon which to base such a claim. Consequently, “MeTube” is not property for purposes of prosecution under 18 U.S.C. §1341. As a result, the indictment should be dismissed. The interpretation of “property” under the Mail Fraud Statute demonstrates that Reg-Dot-Co can claim no value in the domain name “MeTube.” As enumerated above, to be prosecuted under 18 U.S.C. §1341, the scheme at hand must be an attempt to deprive the victim of a property interest. Part of the definition of “property” as interpreted by the courts is that it must have value. Id. Accordingly, the Court has construed this ambiguity to mean the property must “have value in the hands of the victim of fraud.” Cleveland v. United States, 531 U.S. 12, 20 (2000). This cannot be asserted by the government in the case against Mr. Stinson. For example, in Cleveland, the Court dealt with two men who used the postal service to make fraudulent statements in applying for state permission to operate video poker machines. Id. at 15. In holding that property must “have value in the hands of the victim of fraud,” the Court reasoned that poker licenses were not property under the Mail Fraud Statute because the “victim,” the government issuing the licenses, had only a future regulatory interest in the licenses rather than a present value interest. Id. at 20; see also United States v. Murphy, 836 F.2d 248, 254 (6th Cir. 1988) (overturning a mail fraud conviction on the basis that “an unissued certification” of bingo registration is not property due to its regulatory nature and “want of monetary loss”). The cases suggest that the government cannot establish the domain name in question had value “in the hands of” Reg-Dot-Co. 531 U.S. at 20. An item has no value “in the hands of the victim” when it has only potential value as contrasted with current value. Id. Like the government in Cleveland, Reg-Dot-Co only had a potential, future value interest in the name, rather than a present and actual monetary value. In other words, the domain name only had value to Reg-Dot-Co once acquired by a third party. This is exemplified by the undisputed fact that Reg-Dot-Co itself was not “using” the domain name for its own purpose of operating a website under the name. This is much like the situation in Cleveland, where the government was not “using” the licenses for its own profit of operating poker machines prior to issuance. Id. This is also similar to Murphy, where the court held that at unissued bingo license had no value to the government because of a lack of a present “monetary loss.” 836 F.2d at 254. These situations demonstrate that property under the Mail Fraud Statute only has value in a present monetary sense, and this did not occur with respect to Stinson. Not only is the government unable to demonstrate that the domain name “MeTube” had value, but it also cannot demonstrate the elements of exclusivity and transferability. Property under 18 U.S.C. §1341 must be capable of excluding others from obtaining the benefits of that interest, and therefore, transferable by conveyance. 337 F.3d at 1029. The court has held that “exclusivity” is the right to prohibit “others” from reaching the benefits of that interest, while “transferability” is the capability of the property interest to be “sold, traded, or assigned” on the open market. United States v. Alkaabi, 223 F.Supp.2d 583, 590 (D. N.J. 2002). For example, in Alkaabi, the court held that a foreign language standardized testing agency had no property interest in preserving “the integrity of the…testing process.” Id. In coming to this conclusion, the court reasoned that ETS, the testing agency, “did not have an exclusive right” in this interest because it belonged to the community as a whole; as such, the interest could not be transferred “on the open market” and was therefore not a property interest actionable under the Mail Fraud Statute. Id; see also College Savings Bank v. Fla. Prepaid Postsecondary Educ. Expense Bd., 527 U.S. 666, 673 (1999) (remarking that “the hallmark of a protected property interest is the right to exclude others”). Alkaabi demonstrates that the government in Stinson’s situation cannot show Reg-Dot-Co had an exclusive and transferable use over “MeTube,” because the company “did not have an exclusive right” over the name. 223 F. Supp. 2d at 590. Although it is arguable that domain names in general have some degree of exclusive use in that only one holder can use a single name at a time, and that domain names in general have some degree of transferability in that they can be bought and sold “on the open market,” it is simply not in the facts to indicate that Reg-Dot-Co had any basis for asserting exclusive, and therefore transferable, control over “MeTube.” This is similar to Alkaabi because the testing agency had no authority upon which to base their alleged ownership. In Stinson’s situation, Reg-Dot-Co had absolutely no documentation indicating ownership, and they did not openly hold themselves out as using the name. Furthermore, Reg-Dot-Co handed over “MeTube” to Mr. Stinson quickly, showing a general lack of care for the domain names they allegedly possessed Id. Even in cases where an item has been found to be excludable, transferable, and have value, the scenarios support exactly why the domain name “MeTube” is not property here under 18 U.S.C. §1341. For example, in Carpenter v. United States, 484 U.S. 19, 21 (1987), the Court held that a not-yet-published article containing stock information classified as intangible property because the newspaper originally possessing it had exclusive control over the information and the ability to transfer it. Id. at 26. In finding the reporter in violation of 18 U.S.C. §1341, the Court reasoned that the newspaper’s property interest in the financial information had monetary value in its exclusive nature. Id.; see also Int’l New Service v. Associated Press, 248 U.S. 215, 236 (1918) (holding that “news matter…is stock in trade…to be distributed and sold…as any other [valuable] merchandise”). However, Stinson’s indictment is inappropriate because what occurred here is nowhere near analogous to the circumstances in Carpenter. In Carpenter, the Court found that the newspaper had the right to transfer the contents of the column at issue because the newspaper had “exclusive control” over the work product that produced the column. 484 U.S. at 26. Contrarily, in Stinson’s situation, there is no work product, nor any other indication that Reg-Dot-Co had the exclusive right to the domain name “MeTube.” Any other entity could have done what Reg-Dot-Co did by merely claiming a right in the domain name. However, this is not what the courts have intended when defining the necessary exclusivity for purposes of a Mail Fraud prosecution. Id. Another example of a circumstance in which the court found an excludable and transferable property right is that of Kremen v. Cohen. In Kremen, the court concluded that the domain name “sex.com” satisfied the three-part test determining whether an intangible property right exists, because it was well defined, exclusive, and “bought and sold” like “corporate stocks or a plot of land.” 337 F.3d at 1030. However, the factual situation in Kremen is so vastly different from Stinson’s circumstances, that to draw an analogy between the two would test the limits of logic. In Kremen, Kremen had obtained rights to the name “sex.com” directly from the registrar, and had legal authority and documentation to assert his claim over the name. Id. at 1026. Here, Reg-Dot-Co has no analogous basis upon which to assert a similar claim; they have merely been “squatting” on “MeTube” without the legal authority that is clearly present in Kremen. Consequently, it is improper to find Stinson in violation of 18 U.S.C. §1341 under the interpretation of “exclusive use” enumerated by the case law in Carpenter and Kremen. CONCLUSION: For all these reasons, Defendant Stinson respectfully requests this court to dismiss Plaintiff United States’ charge in violation of 18 U.S.C. §1341 as the facts of this case conclude that the domain name “MeTube” is not “property” under the statute as defined by the relevant case law. Respectfully Submitted, 9478 #9478 Counsel for Defendant 1801 Euclid Ave. Cleveland, OH 44115 (216) 123-4567 CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE: The foregoing Motion to Dismiss and attached argument was served on opposing counsel by ordinary mail this 12th day of March, 2010. ______________________________ 9478 Counsel for Defendant