THE EU, NAFTA, MERCOSUR

advertisement

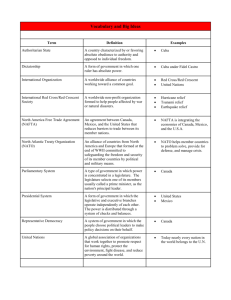

MERCOSUR AND NAFTA - Globalisation and Regionalism LECTURE NOTES Regional trade agreements: compliment or distraction of multilateral trade system? a) The official stance: GATT (1947) and WTO (1995). Key rule of the multilateral trade system: reductions in trade barriers should be applied, on a most-favoured nation basis, to all WTO members. SO no WTO member should be discriminated against by another member's trade regime. Important exception: Article XXIV of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) – allows for regional trade agreements (RTAs), under which reductions in trade barriers only apply to the countries that form the arrangement. b) Alternative approaches: 58% world trade conducted RTAs (2008) 400 operating by 2010. “The conventional wisdom is that the move toward regionalism in the post-Cold war era is a step (a “building block”) towards globalisation rather than an alternative to it. [Events are] challenging the conventional wisdom” (Mario Esteban Carranza, South American Free Trade Area or Free Trade Area of the Americas?, Hants, 2000, p. 2). c) Change of policy of the WTO (Doha, 2003). “RTAs can potentially hinder the objective of a coherent and transparent multilateral trading system (MTS) by discriminating against third parties, distorting trade flows, and by detracting limited resources from multilateral to regional and bilateral trade negotiations. As their number and scope expand to include complex regulatory trade provisions, trade in services and investment-based activity, the importance of improving the formal and substantive links between RTAs and the multilateral trading system (MTS) is becoming apparent. Even more so as no effective multilateral surveillance mechanism is in place to address those cases where RTAs may not be in line with the spirit of WTO fundamental principles; this may result in unbalances between the liberalization efforts being pursued regionally and multilaterally and increasingly generate tensions”. http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/region_e/sem_nov03_e/background_obj_e.ht d) New transparency mechanism (2006). Three types of substantive conditions for regional agreements to be WTO consistent. - obligation not to raise barriers to trade with third parties. a customs union must harmonise the external trade policies of its members and compensate affected non-members accordingly. tariffs and other restrictive regulations of commerce must be phased out on “substantially” all trade. Regional Trade Agreements (RTAs): a) Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). “An FTA is an arrangement which establishes unimpeded exchange and flow of goods and services between trading partners regardless of national borders. An FTA does not (as opposed to a common market) address labour mobility across borders, common currencies or uniform standards or other common policies such as taxes. Member countries of a free trade area apply their individual tariff rates to countries outside the free trade area” (http://www.tradeport.org/library/f.html). Examples: EFTA (1959: Iceland, Norway, Liechtenstein and Switzerland) ASEAN Economic Community (1967: Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, Lao, Myanmar, Cambodia) CEFTA (1992: Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovenia), BAFTA (1993: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) NAFTA (1994: Canada, USA, Mexico).. b) Customs Unions (CUs). “An agreement between two or more countries to remove trade barriers with each other and to establish common tariff and non-tariff policies with respect to imports from countries outside of the agreement” http://www.tradeport.org/library/f.html). Examples: SACU (1910: Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland); EEC (1957: 27 MS) CARICOM (1973: Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, Surinam, Trinidad and Tobago) MERCOSUR (1991: Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Venezuela) COMESA (1993:Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Lybia, Sudan, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe) Andean Pact (1996: Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru).. The distinguishing features of NAFTA. a) Size: The most ambitious free trade agreement yet. World’s largest free area: 450 m. b) Countries involved: It aims to integrate economies that are poles apart. Mexico’s economy = c.a. 20% of US economy. c) Extent of the agreement: Elimination of most trade and investment barriers (over a 15 year period). Opening of previously protected sectors: agriculture, energy, textiles, automotive trade. Side agreements: Environment (NAAEC: North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation) Labour standards (NAALC: North American Agreement on Labour Cooperation) Production partnerships: design, manufacturing, assembly (maquiladoras) New corporate investment rights and protections, which are unprecedented in scope and power NAFTA (1994-2010): brief history The next stage in the U.S.-Canadian Free Trade Agreement (1988) Signature: December 1992 (G. Bush). Ratified by U.S. Congress (November 1993, Clinton, 234 favor-200 against) Took effect: January 1, 1994 Fast track: August 2002. Transfer of Powers from Congress to the Executive In 2005, Congress voted to extend NAFTA to five Central American countries through the Central American Free Trade Agreement Bush administration wanted to add Peru and Colombia to the list as well. 2008 - last of NAFTA’s transitional restrictions governing U.S.-Mexico and Canada-Mexico agricultural trade removed. 4. NAFTA facts (1994-2010): a war of numbers. Positive effects (Source: US Department of Commerce (2010), CATO Institute). Mexico investment in the US (280%) 18 million US jobs created US investment in Mexico (242%) Special programs for workers displaced Trade US and NAFTA partners (111%) Manufacturing output in the US (41%) Dramatic economic and political transformation of Mexico (end of PRI, Fox, Calderón) Negative effects Mexico Effect of US imports on Mexican farms (corn) 70% drop in prices to Mexican farmers 1.5 million immigrants to the cities Chiapas conflict: the indigenous communities Zapatistas (1-11994). Industrialization of the border (Toxic dumping and water contamination). Expansion of foreign-owned assembly plants (maquiladoras) Declining average wage (peso crash in 1995). Illegal immigration in the US No technology transfer due to specific NAFTA investor provisions No development of a Mexican independent industrial base Disconnection from domestic industries (retailing sectors). Growing social inequalities Negative effects US US work force shifted away from manufacturing Job relocation (500.000 jobs lost) Stagnation of real wages. Increased income inequality “NAFTA model devastates Mexico’s rural sector while poverty increases” (PCitizen) • Before NAFTA, 36% of Mexico’s rural population earned less than the minimum needed for food This number grew by nearly 50% in the agreement’s first 4 years. The percentage of the population in this state of poverty in Mexico today remains roughly where it was before NAFTA despite the promises made by the pact’s proponents. • Washington Post - on the 13-year anniversary of NAFTA, “19 million more Mexicans are living in poverty than 20 years ago Mexican government and international organizations - about 24 million – nearly one in every four Mexicans – are classified as extremely poor and unable to afford adequate food.” • The number of undocumented immigrants in the United States (who are mostly Mexican and Central American) increased 18%, from 3.9 million in 1992 to 12 million in 2007. (http://www.citizen.org/trade/nafta/). NAFTA 15 Years Later: The Balance Sheet NAFTA supported in Mexico because, in theory, intra-continental free trade would allow the country to take better advantage of its greatest economic asset: its geographical proximity to the largest economy in the world, the United States, as well as to another economic power, Canada. Facilitating unfettered access to these countries was seen as critical to bringing the benefits of globalization to Mexico. Goods that could be produced more cheaply in Mexico could be exported to US and Canadian consumers; American and Canadian technology and investment would flow to Mexico. Accomplishments: Trade among the three countries did, in fact, increase dramatically, 227% between 1993 and 2008, according to the World Bank. Trilateral trade currently accounts for $15.3 trillion in goods and services annually. Mexico’s share of this trade, which had previously been dominated by USCanadian trade, also increased dramatically. Mexico’s imports from Canada rose 704%; its exports to Canada rose by 482%. Mexico’s imports from the US rose by 236%; its exports to the US rose by 440%. All three countries have experienced GDP growth. The US and Canadian grew by 53% the Mexico by 51%. (Remembering that percentage growth of larger economies like the US and Canada yields much greater absolute gains than percentage growth in an economy like Mexico – they started at dramatically different levels, pre-NAFTA). Disappointments: The Mexican economy did not grow as much as expected. Inequality and poverty have persisted. Slow wage growth for workers continues to harm domestic consumption and overall domestic growth. Many had hoped that NAFTA would decrease immigration from Mexico to the United States by creating Mexican jobs. T his has not been the case, with over 500,000 Mexican immigrants entering the US every year. Technological advances have come slowly to Mexico. Most industry is still in the low-value added sector, which means sophisticated parts are manufactured elsewhere and shipped to Mexico for assembly only. This results in only a small part of the profit from these goods remaining in Mexico. Mexican workers remain under-educated and under-trained, relegating Mexican industry to a less lucrative place in the global supply chain. Mexican agricultural exports have grown more slowly than anticipated, largely due to competition from large agricultural enterprises located inside the United States and protected by US government subsidies. Mexican farmers retain an advantage in crops that are hand-picked, such as avocados and strawberries, but many farmers, especially those producing corn, have been hurt by the dismantling of tariffs that protected them from cheap subsidized US imports. Some would say that the intensification of the drug war is to some extent linked to NAFTA – opening borders to legitimate trade has also facilitated trafficking in illegal substances and guns. Why the Disappointment Associated with NAFTA? Examinations of what NAFTA has and has not done for the Mexican economy are plagued by misperceptions about what NAFTA is and what it is not. From the beginning, expectations for the trade pact probably exceeded what could realistically be accomplished. Internal factors within Mexico and unanticipated global trends have also had an impact on what is often referred to as NAFTA’s “underperformance.” Problems with the Pact: Free trade can be painful → competition eliminates some kinds of jobs. NAFTA lacks many of the cushioning measures for populations which would not benefit from globalization (include social safety nets for the displaced and unemployed and labor standards for workers). Few provisions for the mediation of trade disagreements. NAFTA’s focus is on eliminating tariff barriers; it neglects other protectionist measures. e.g. US agricultural subsidies have gone unaddressed and continue to affect the competitiveness of Mexican exports. Implementation has been uneven. e.g. a provision designed to allow Mexican trucks to deliver products in the US was rejected by the US Congress in early 2009. Both labor and environmental standards are largely missing from NAFTA, leading to unsafe working conditions in factories on both sides of the USMexico border and to environmental degradation in border towns where large populations have settled. Problems within Mexico: NAFTA’s failure to live up to Mexican expectations has a lot to do with Mexico’s own internal economic policies. Instability characterized by swings between the ideological left (pro-labour) and right (pro-business) have discouraged foreign direct investment and hampered macro-economic planning. Powerful oligarchs continue to call the shots in many sectors of the economy, interfering with the development of cohesive trade policies Challenges in the mid-1990s (unrelated to NAFTA) led Mexico to get a late start in capitalizing on NAFTA (included a debt and currency crisis, the assassination of a Presidential candidate, and the Chiapas uprising in the first years of the pact) Mexico’s lack of education infrastructure → unable to protect workers from free trade dislocations or to develop more lucrative higher-end manufacturing. The US and Canada - edge in their capacity to retrain workers and move them into other industries harmed by Mexican competition. Mexico’s lack of infrastructure has limited its ability to take advantage of NAFTA. With its population spread throughout the country and its infrastructure underdeveloped, mobility of labour and goods is compromised. Cities along the border are burdened by transient populations and poor urban planning associated with boom and bust trends. Moreover, poor infrastructure leads to bottlenecks (a narrow section of road where traffic flow is restricted) in and around Mexico City through which nearly all Mexican goods produced in the South must travel. Unanticipated Trends and Events: September 11, 2001 - awakened security concerns at the US-Mexico border, and led to a tension between economic activity and counter-terrorism efforts. The Wilson Center has estimated that $9 billion is lost each year in USMexico sales and investment due to wait times at the now highly fortified border. Keeping trade moving while keeping populations safe from external threats has proven challenging. China’s entrance onto the economic world stage has had perhaps the greatest effect on the promise of NAFTA for Mexico. Bilateral trade deals between all the NAFTA partners and China have resulted in stiff competition in the area of manufactured goods. China’s factories employ more workers with better education levels, and enjoy more state promotion of industry than those in either the US or Mexico. Chinese imports account for job losses in the US and Mexico that are often wrongly attributed to NAFTA on both sides of the border. Recession - highlighted the volatility associated with the global marketplace, and Mexico is suffering in numerous ways. Exports are falling in response to reduced consumer demand in the US, reduced US investment in the Mexican economy, and a steep decline in remittances from Mexican workers who have lost their jobs in the US. Swine flu - effect on tourism The Mexican economy is now facing its greatest challenge since the peso crisis in 1995. Are free trade and social integration compatible? “Even if free trade maximises economic wealth (and therefore, potentially at least, economic welfare), it still cannot be said that everyone will be better off unless compensation is paid to those whose income falls. This income distribution effect constitutes an important argument against free trade and poses a serious practical obstacle to the free trade doctrine” (Douglas A. Irwin, Against the Tide, 1996, p. 219). MERCOSUR: brief history (1991-2010) Treaty of Asunción (March 26, 1991): Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay: The Ouro Preto Protocols (December 1994): A Customs Union. Associated members: Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Perú Full membership: Venezuela (2010). Structural Problems. a) Asymmetry of economic power (Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, Venezuela). b) Divergence in domestic policies: Mercosur’s internal battle Brazil: autonomous industrialisation, diversification and “open protectionism” devaluation of the real (1999, 2001) and its effects Argentina: market-oriented strategy due to the need of capital goods (fin. crisis of the 80’s). alignment with US-driven MIF policies (The Multilateral Investment Fund = independent fund administered by the InterAmerican Development Bank (IDB), created in 1993 to support private sector development in Latin America and the Caribbean. Stated goal = provide technical assistance and investments to support micro and small business growth, build worker skills, and to improve markets and access to finance) single-currency tied up to the dollar vulnerability to capital flights collapse of Argentinean economy (2001). Venezuela state-run economy (largely based on petroleum sector) c) Contradictory strategies: Trade disputes: institutional deficit. Lack of alignment of macroeconomic policies Becoming politicised and moving away from its free-trade origins d) Slow development of supranational institutions: Common Market Council Mercosur Parliament (2006) General Secretariat “Globalization is not irreversible. If there is a backlash against globalization at the international level; if, after the victory in Seattle, the antiglobalization movement wins further battles against globalization, domestic actors (such as Argentine, Uruguayan, and Paraguayan business and labor organizations negatively affected by the Brazilian devaluations and the Argentine crisis) will recover the initiative at the regional level, increasing the prospects for Mercosur's survival as an autonomous trading bloc”. Mario E. Carranza, Can Mercosur survive? Domestic and international constraints on Mercosur, http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa4000/is_200307/ai_n9289210/pg_22/ Future scenarios of regional trade agreements in America. a) From Mercosur to SAFTA/UNASUR (2008) Widening and deepening Common currency/Common market Coordination of macroeconomic policies From intergovernmental model to supranational institutions Cooperation Agreement with the Andean Community trade bloc (2005) UNASUR: intergovernmental union integrating two existing customs unions: Mercosur and the Andean Community of Nations, as part of a continuing process of South American integration. It is modeled on the European Union. 12 MS (except French Guyana). Aims: Providing Unasur with a defined political leadership on the global stage. Establishment of a permanent bureaucratic body for the supranational union, eventually superseding Mercosur and CAN political bodies. The Unasur Constitutive Treaty was signed in Brasília in 2008, Brazil. The South American Parliament will be in Cochabamba, Bolivia The headquarters of its bank, the Bank of the South are located in Caracas, Venezuela. May 2010 - former Argentine President Néstor Kirchner was unanimously elected the first Secretary-General of UNASUR for a two-year term,. Vacant after his November 2010: South American Summit (democratic clause to Constitutive Treaty). b) From Mercosur/Nafta to FTAA (ALCA) First Summit of the Americas (Miami 1994): FTAA 2005 Second summit of the Americas (Santiago 1998): the new role of Brazil Third Summit of the Americas (Quebec 2001) 7th Ministerial Meeting (Ecuador, October 2002). Fourth Summit of the Americas (Monterrey, 2004). Refusal of Venezuela, Brazil, Argentina and Bolivia to sign the agreement. Divide et impera? (CAFTA, 2004, Chile (2004), Perú (2007), Colombia, Panamá FTAs, 2007-2010). c) Bilateral Agreements. EU-Mercosur Interregional Framework Co-operation Agreement (1995): 2006. Ministerial meetings: 1996-Luxembourg, 1997-Noordwijk, 1998Panama City, 2000-Vilamoura, 2001-Santiago de Chile, 2002-Madrid, 2003-Athens,…., 2008-Buenos Aires, Madrid (2010). The world’s largest free trade area? BRICs Fixing Nafta's flaws US trade agreements should let nations set their own priorities, rather than be undermined by private companies Kevin Gallagher and Timothy Wise guardian.co.uk 7 January 2010 Obama is attempting to In a welcome move, President Obama's US trade representative, Ron Kirk, Obama is attempting to negotiate the Trans-Pacific partnership agreement (TPP) - a proposed eight-country trade deal with countries as diverse as New Zealand, Chile and Vietnam. would be the largest US endeavour NAFTA US trade representative, Ron Kirk, still to unveil many specifics BUT a 21st century trade agreement that brings growth, stability, and prosperity to the US and its trading partners will have to abandon the out-dated Nafta-model. US Nafta blamed for : job losses adding downward pressure on wages, particularly in manufacturing contributing to a large US trade deficit Canada blamed for : job losses declining competitiveness of the manufacturing sector constraints on Canada to deploy adequate policies for public welfare. Mexico slow growth weak domestic investment anaemic job creation increased economic vulnerability – decimating many existing sources of livelihood, particularly in agriculture Mexico's economic performance is now among the worst in the hemisphere. In all three countries, legal scholars and government officials decry the capability granted for foreign investors to sue governments if legislation negatively affects their profits or expected profits. Report ‘The Future of North American Trade Policy: Lessons from Nafta’ – some Bush-era changes to the US trade template for making minor but significant modifications in some labour, environmental and intellectual property provisions that were later reflected in US-Peru free trade agreement. BUT these reforms do not go deep enough to fix the flaws in Nafta and establish a template for a 21st century trade agreement. The report offers proposals for fixing provisions on labour, agriculture, investment, services, intellectual property and the environment. It also discusses development finance and migration Key recommendation : any 21st century trade agreements should not elevate the rights of private firms over governments and should provide safeguard measures to make sure nations can adequately address financial, environmental and development-related challenges. Currently, US trade agreements allow private companies to undermine national efforts to regulate for the public interest. Obama should also fulfil his promise to fix Nafta. Canada and Mexico are the US's first and third biggest trading partners and account for more than one quarter of total US trade. Key to revitalizing Nafta would be a reforming the rules and invigorating the North American Development Bank to help address development asymmetries among Nafta partners that have only been accentuated by the agreement. Nafta should not merely serve as a pilot project for other, less economically important, trade agreements. Nafta's failures in Mexico have direct repercussions in the United States, be it migration, the drug trade or weak demand for US exports. Latin American Perspectives Miguel Tinker Salas Despite a complex political environment and an uncertain economic future, conditions continue to favor the general forces of the left and popular movements in Latin America. e.g. - 2008 Paraguay - elected Fernando Lugo, ending the near-70-year monopoly of the Colorado Party. - Ecuador adopted a new constitutionthat altered long-standing political arrangements Bolivia - Evo Morales, defeated efforts by the right and regional economic and political elites (with support from the United States) to create conditions of ungovernability, manipulate racial differences, and divide the country. BUT end of 20thC = v different Almost every country = military dictatorships. Dictators ruled in Paraguay (1950s), Brazil (1964), Bolivia (1971), Ecuador (1972), Chile (1973), Uruguay (1973), and Argentina (1976). US either directly involved in the coups, turned a blind eye, acquiesced, or legitimated the military by recognizing its government and providing loans. 1980s - U.S. efforts to contain Nicaragua and its pursuit of a military solution to the problems in El Salvador plunged Central America into a decade-long conflict Cuba struggled after the demise of the USSR and the U.S.-imposed blockade worsened conditions on the island. The human cost of the military regimes and the economic policies they implemented → adoption of neoliberal economic polices during the 1980s and 1990s. The billions of dollars the military regimes had borrowed = huge debt that debilitated the economies of the region even after limited democracy had been restored. Adoption of neoliberal economic policy → : increased levels of inequality the dismantling of traditional labor movements a dramatic expansion of the informal market a reduction in the size of the middle class unparalleled levels of immigration environmental devastation increased levels of feminicide and a reduction of the role of the state as an arbiter in social disputes. Neoliberal policies eliminated food subsidies that helped the poor and opened the agricultural sector to competition from highly subsidized U.S. agribusiness. Devastation results → thousands of farm workers, peasants, and indigenous people were forced off their land. In Mexico, for example, the agricultural sector was decimated and millions of people were forced to find employment in the United States. As the state retreated, organized crime— narcotrafficking—quickly filled the void and became a state within a state, creating its own army and permeating every aspect of society. NOW (contrast) - elected leftist or broad left-of-center governments continue to maintain popular electoral majorities or hold the presidency in Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Panama, Nicaragua, and Guatemala. Obviously, there is not and cannot be a single left agenda in Latin America. Political parties, electoral coalitions, and popular movements are the product of different historical experiences and relations of power; how they adapt to these concrete conditions will vary in each country. BUT There are some issues that unite the countries—esp the promotion of regional integration (the Union of South American Nations [UNASUR], CARICOM, the Rio Group)→ a multipolar international foreign policy that rejects the idea of the United States as the only superpower, and general policies that favor social movements and the poor(in particular, access to food, education, and health services). ALTHO the political realities in each country remain distinct and do not permit generalizations, important economic and political changes have occurred since the early and mid-2000s, when many left parties and the electoral coalitions they constituted gained power. 1)When left forces came to power - the prices of export commodities (eg oil, natural gas, tin, copper, agricultural products) = high. 2) China emerged as an important commercial alternative to the United States. 3) More European capital, with Spain often taking the lead (especially in banking and telecommunications These conditions generally provided increased budgets that permitted leftist governments to promote social spending to lessen the poverty and inequality that had increased dramatically with the single-minded promotion of neoliberal economic dogma beginning in the 1980s. Despite political change, the crisis has exposed the extent to which many countries continue to be dependent on exports to the industrialized countries. The Right Throughout L.A. - the political right and its often centrist allies retreated in disarray. The turmoil also took its toll on traditional social democratic and even socialist parties that had cast their lot with the neoliberals and were ousted by a radicalized electorate. Election of Hugo Chávez (1998) - Venezuela became a laboratory not only for alternative leftist social policy (creation of parallel institutions, social missions, popular power) but also for right-wing experimentation with the use of the private mass media to organize political forces where the traditional political parties had lost credibility. The right has promoted ungovernability (known in Venezuela as guarimba), spearheaded strikes or concerted action by leading economic sectors (oil industry or food shortages), and even staged a military coup. A key component of this strategy has been the mobilization of the relatively small but influential middle class to generate and sustain public opinion against social change, since this sector always fears that economicchange will produce a decline of its precarious standing in society. The lessons learned in Venezuela by elites, the right and their political allies, the United States, and the leadership of the Catholic Church have now been applied throughout Latin America, especially in Bolivia (regionalism and ungovernability), Argentina (strikes by export sectors), and Ecuador (media campaigns). The use of the media as part of the arsenal of the right has also been critical in Mexico The reappearance of an emboldened right, with the support of the United States, the commercial mass media, and the upper echelon of the Catholic Church, requires serious reflection by left forces in the continent. The left in power Challenges from the right and from the United States ALSOr from having to govern countries as distinct as Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Brazil. Significant change for the left (traditionally in the role of the opposition or, in some cases, as part of an armed insurgency challenging a repressive state). The defining feature of political change in Latin America today is that political power has been obtained through the ballot box and not on the battlefield. → a unique set of challenges on left forces in the region in that the electoral arena is now the primary setting for validating power and proposing structural change. SO we have seen Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador adopt new constitutions that empower the popular sectors,mass movements, labor, women, black people, indigenous groups, etc. This forces political elites to compete on a more level playing field. Adopting new constitutions, however, is only the first step toward altering the balance of power in the region. Political and cultural change can be intimidating, even for the very people it seeks to benefit. It clashes with age-old cultural, social, and political arguments (conventional wisdom) informed by notions of modernity, progress, traditional sources of knowledge (socalled experts), national unity, racial democracy, and the importance of relations with the United States. Left governments have to translate macro-social policies into concrete results that benefit the population constantly being contested by the forces of tradition. ALSO contested environment - economic and political elites continue to hold tremendous power and have powerful allies in the Church, the middle class, the media, and the United States. The Challenges of Governing The rise of the left has generated new expectations for improved living conditions. If these expectations remain unfulfilled, they will threatenthe left’s ability to retain power. Through the mass media, which promote consumerism as a symbol of progress, the opposition plays on fears of a declining standard of living. Leftist governments have a mixed record; because of the dynamics of local or municipal power, they are often better at ending illiteracy and delivering medical services than at removing rubbish from the streets or fixing potholes. Crime (paralleled the rise of inequality during the heyday of neoliberal economic policy) remains a significant problem in every Latin American country. ALSO reported more in gradually undermines public faith in elected governments and helps influence public opinion. The left lacks a trained professional cadre of administrators or bureaucrats with political or social consciousness who are also familiar with the complexities of state power. Despite new governments and parties, old political cultures and habits die hard. In Mexico; the PRD has become the repository of dozens of former Partido Revolucionario Institucional (Institutional Revolutionary Party—PRI) officials, who, unable to win posts in their organization, have switched to the center-left party. The result has been important divisions in the PRD between those who see the party largely as a mechanism for securing an elected post and propose to “modernize” the PRD and those who see the party as a reflection of social movements while also pursuing an electoral strategy. The reality is that the population will judge those in power, left or otherwise, in terms of improvements in their quality-of-life situation or social conditions in their community and, absent these improvements, may vote against those in power. The shift from Bush to Obama Many believe that the Bush administration “abandoned” Latin America. While it is true that its actions were constrained by its invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, the reality is that the United States was never fully disengaged in Latin America. During its eight years in office, the Bush administration was both directly and indirectly involved in the region. In the guise of the war on drugs and later terror, it expanded its military and intelligence presence throughout Central and South America. The Bush administration, with Condoleezza Rice as head of the State Department, at first sought to “inoculate” Latin America from the Chávez government while promoting Brazil’s Lula as an alternative to Venezuela. WHEN Bolivians elected Evo Morales and Ecuadorians elected Rafael Correa, Venezuela was no longer the only country in the region with a decidedly left government. → Faced by these changes, increasingly the Bush administration, the mass media, and the Washington think tanks promoted the notion of Brazil’s Lula as the moderate (positive) leftist and Chávez as the radical (extreme). This way of framing the issues clashes with the fact that many Latin American leaders, including Lula, have on multiple occasions supported Chávez and spoken highly of his contributions to regional integration. The tactic of relying on Lula as a counterweight to Chávez remains the hallmark of the failed Bush policy toward Latin America. Obama would be ill-advised to adopt this approach. Regardless of its rhetoric of change, Obama’s government will not undermine the fundamental asymmetrical structures of power that have historically framed relations between Latin America and the United States and the rest of the world. What will Obama do in Latin America? Undoubtedly, four years from now, political analysts in Washington will be lamenting that, rather than Iraq and Afghanistan, it was the economic crisis that prevented Obama from fully engaging with Latin America. The reality, however, is that with Hillary Clinton at the helm of foreign policy we can expect little change with regard to the region. His keeping Bush-era appointees incharge of Latin America policy until the Trinidad summit does not suggest that change is forthcoming. Another important area in which the new administration can influence policy in terms of Latin America is immigration. The remittances that immigrants provide to their family members in their home countries are the difference between poverty and survival. Obama promised that during his first 100 days in office he would introduce immigration legislation aimed at regularizing the status of millions of undocumented Latin Americans in the United States. Though he may introduce legislation, it is doubtful that Congress will consider this a top priority in the present economic environment. Mexico Shortly after winning a highly contested presidential election, Felipe Calderón launched his so-called war on the drug cartels – a break from political negotiations → produced more than 8,000 reported deaths in two years and unprecedented militarization of Mexican society. Faced by corrupt state and municipal police forces, the federal government has used the military to wage war on the traffickers. Besides human rights issues and matters of due process, this raises the specter of a military that has been corrupted and infiltrated by the cartels in the same way as the police forces. The much-touted Plan Mérida (emulating Plan Colombia) is expected to “rescue” Mexico from this situation. Initially envisioned as a North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), it subsequently evolved into a plan signed by Bush and Calderón with a first installment of US$400 million going to the military and federal prosecutors. While ensuring the continued militarization of Mexican society, this plan will do little to reduce the suffering of the Mexican people who are exposed to this violence. The military and intelligence apparatus that is being created can be just as easily used, as it has been in Colombia, against social movements as against crime syndicates. January 1, 2009= 15th anniversary of the Zapatista uprising that shook Mexico on the eve of the introduction of NAFTA. Fifteen years later, much of what the Zapatistas predicted has transpired : the countryside has been devastated small business and commerce face bankruptcy millions of Mexicans have been compelled to abandon their country. As Bush did in the United States after 9/11, the Calderón administration has skillfully used the war on the cartels to promote support for the government and limit criticism of its actions. Conclusion The process of political change in Latin America is still in its initial phase. Although the balance of forces still favors the left, the changes are not irreversible; quite the contrary, they are constantly being contested by internal forces and their allies abroad. The powerful forces that favor the traditional order— economic and political elites, segments of the middle class, and the hierarchy of the Catholic Church—vigorously defend the privileges they have historically enjoyed. With the nomination of Hillary Clinton as secretary of state, many of these forces are expecting a “liberal” ally in the White House. Limiting the left in Latin America by purporting to promote lofty social programs and employing the rhetoric of cooperation has been the hallmark of liberal governments in the United States. However, the economic crisis reduces the ability of the United States to promote such initiatives. If Obama repeats the failed policies of the Bush and other administrations, the United States risks further isolation in Latin America. For many countries the United States is no longer a central policy concern. Elections will once again take center stage in Venezuela, Bolivia, and El Salvador, and the results may determine the future of the political process in each of these countries. If Chávez loses in Venezuela, left forces will have to rally around a new candidate who can win in 2012; such a figure has yet to materialize. With the constitution approved in Bolivia, Morales will now be able to run for a new term as president, an election he is expected to win. In El Salvador, if the ARENA party relies on vote fraud or violence to defeat the FMLN, many will begin to question the electoral process and the viability of the peace accords. Regional integration, which has proceeded in times of relative economic stability, will now be tested as disputes between smaller and larger countries become more intense. The Rio Group, UNASUR, CARICOM, Petro-Caribe, and other regional bodies will confront new challenges Governments of the left, which have adopted new social and economic policies and mobilized important sectors of the population, may actually be in a better position than others to confront the challenges that arise from the economic crisis. By politically empowering the population, they have made important sectors advocates for their own communities. As the experiences of Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador have shown, communities organized under popular forms of political participation make demands, defend their interests, and expect accountability. Governments such as those of Peru, Colombia, and Mexico that continue to advocate neoliberal economic policy may be in the worst political position to withstand the effects of the crisis. Conditions in Latin America remain complex and difficult to decipher, much less predict. The depth and duration of the economic crisis will test the true commitment of governments to implementing social change as they are forced to choose between social spending, debt repayment, military budgets, and a host of other obligations. If the crisis serves as a pretext for retreating from change or empowerment of the population, this will weaken support for left governments in the region. Where they hold power, political leaders and social movements will have to strike a balance between the lofty goals of social transformation and the actual task of governing in an environment in which people still expect palpable improvement in their daily lives. INFORMATION Doha - The Doha Development Round = the current trade-negotiation round of the WTO - started November 2001 Objective = to lower trade barriers around the world, which will help facilitate the increase of global trade. As of 2008, talks have stalled over a divide on major issues, such as agriculture, industrial tariffs and non-tariff barriers, services, and trade remedies. The most significant differences are between developed nations led by the European Union (EU), the United States (USA), and Japan and the major developing countries led and represented mainly by Brazil, China, India, South Korea, and South Africa. There is also considerable contention against and between the EU and the USA over their maintenance of agricultural subsidies—seen to operate effectively as trade barriers. The Doha Round began with a ministerial-level meeting in Doha, Qatar in 2001. Subsequent ministerial meetings took place in: Cancún, Mexico (2003 Hong Kong (2005) Related negotiations took place in: Geneva, Switzerland (2004, 2006, 2008) Paris, France (2005) Potsdam, Germany (2007). Chiapas conflict: the indigenous communities Zapatistas (1-1-1994) The Zapatista Army of National Liberation (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, EZLN) is a revolutionary leftist group based in Chiapas, the southernmost state of Mexico. Since 1994, the group has been in a declared war "against the Mexican state" This war has been primarily nonviolent and defensive against military, paramilitary, and corporate incursions. Their social base is mostly rural indigenous people but they have some supporters in urban areas as well as an international web of support. CARICOM The Caribbean Community (CARICOM) an organisation of 15 Caribbean nations and dependencies. main purposes - to promote economic integration and cooperation among its members, to ensure that the benefits of integration are equitably shared, and to coordinate foreign policy. major activities - coordinating economic policies and development planning; devising and instituting special projects for the less-developed countries within its jurisdiction; operating as a regional single market for many of its members (Caricom Single Market); and handling regional trade disputes. Petro-Caribe Petrocaribe S. A. is a Caribbean oil alliance with Venezuela to purchase oil on conditions of preferential payment. Launched in June 2005 Treaty of Asunción (March 26, 1991): signed in Asunción, established Mercosur. Later, the Treaty of Ouro Preto (1994) was signed to supplement the first treaty, establishing that the Treaty of Asunción was to be a legally and internationally recognized organization. Collapse of Argentinean economy (2001) Argentine economic crisis was a financial situation that affected Argentina's economy during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Macroeconomically speaking, the critical period started with the decrease of real GDP in 1999 and ended in 2002 with the return to GDP growth, but the origins of the collapse of Argentina's economy, and their effects on the population, can be found in action before. Antiglobalisation victory in Seattle 30 November 1999 - when protesters blocked delegates' entrance to WTO meetings in Seattle, Washington, USA. The protests forced the cancellation of the opening ceremonies and lasted the length of the meeting Brazilian devaluations Investors had worried the real was overvalued, leaving Brazil vulnerable to financial contagion. Contagion = when a financial crisis in one country motivates investors to remove their funds from other countries with similar weaknesses. When financial crises swept Asia in 1997 and Russia in 1998, investors who were pulling their investments out of those countries also began to withdraw them from Brazil. To discourage the outflow of dollars, which the central bank would have to supply to maintain the pegged exchange rate, Brazil raised interest rates—a step intended to entice investors to hold their money in Brazil to earn high interest rates. ALSO SEE : BOOK ON VISION http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/region_e/sem_nov03_e/background_obj_e.ht http://www.tradeport.org/library/f.html http://www.citizen.org/trade/nafta/ www.worldsavvy.org http://www.c-spanvideo.org/program/293812-5 - video