Pilgrimage and Towns in Medieval Christianity

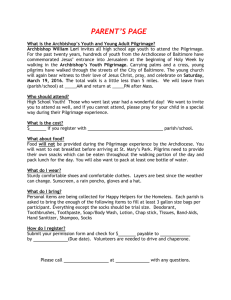

advertisement

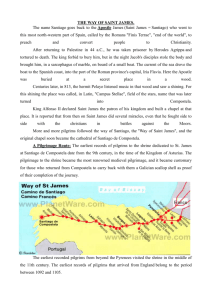

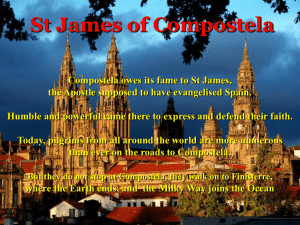

1 Pilgrimage and Towns in Medieval Christianity Jaehyun Kim Korea Institute for Advanced Theological Studies I. Introduction: Medieval Christianity and Pilgrimage II. Christian Pilgrimage and Towns a) Towns on the Way to Pilgrimage b) Holy Turning Point: Compostela c) Pilgrim and Development of Towns d) Towns and the Encounter of Pilgrims: From Solidarity to Understanding III. Conclusion I. Introduction: Medieval Christianity and Pilgrimage Various social-cultural factors were crucial in the formation and development of medieval towns. As we see in Trier, Roman architecture and roads were important for establishing towns far before Christianity provided a culturalreligious framework. Feudal systems and commercial and trade development, both on regional and international levels, played a major role in flourishing medieval culture. In addition to these factors, there is no arguing that medieval Christianity greatly contributed to the formation of medieval towns. Cathedral organizations, monasteries, and pilgrimage were decisive to the life and culture of medieval people. Christian villages and towns were formed alongside old pagan villages. However, new towns like Cluny and Bezlay were made through the burgeoning monastery and as a result of pilgrimage. Monasteries, religiously secluded communities, paradoxically became politicalcultural centers. Christian theology, especially scholasticism in the thirteenth century, rapidly increased primarily in towns and cities. Christian pilgrimage was important for medieval towns and cultures. ‘Pilgrimage’ means visiting religious places where certain meaningful and important events happened, to entreat supernatural help and also keep religious responsibilities. Even before the birth of Christianity, a number of places emerged as major pilgrim centers like Jerusalem for Judaism and Mecca and Media for Islam.1 Major places primarily related to Jesus, such as the places of 1 Simon Coleman & John Elsner, Pilgrimage: Past and Present in the World Religions 2 his birth, death, passion, and ascension, made Jerusalem a well-known international pilgrim center. The life of Jesus, a model for ensuing martyrs and saints, transformed a normal place, Jerusalem, into sacred space. From its very early stages, Christianity began to develop pilgrimage. Horrible persecution by the Roman Empire against Christians and the Christian diaspora sometimes made it difficult for Christians to access Jerusalem. The unshakable status of Jerusalem as an international pilgrim center, however, continued for a long time. Hieronymus’s letter to Paula and Marcella indicates that not a few women traveled from Rome to Jerusalem in a very early stage of Christianity.2 Christian pilgrimage developed not only within orthodox Christian circles but also in various Christian sects including the Donatists in Northern Africa. What is important is that pilgrimage was growing along with the towns.3 It was, however, during medieval Christianity that pilgrimage spread all over Europe. Pilgrimage places in the early medieval period were categorized into three levels: international, national, and regional. For instance, Jerusalem where Jesus lived and died, and Rome where Peter and Paul gloriously ended their lives, became international pilgrim centers. Towns like Paris, Fulda, and Einsiedeln became famous national pilgrim centers. And numerous regional pilgrim centers inspired the faith and imagination of medieval Christians. Byzantine Christianity dwindled as Islam expanded beginning in the seventh century. Major Christian areas shifted from the Mediterranean to northern Europe and also medieval Christians began to have a different understanding as to the places for pilgrimage. With the change of politico-religious terrain, the role of Jerusalem and Constantinople were diminished. Instead of traditional pilgrim centers, people sought alternative and safe passages to pilgrimage. Consequently, the importance of Rome as an international pilgrimage location gradually increased. P. Geary discusses many interesting topics on early medieval pilgrimage with a specific emphasis on “holy theft”(furta sacra). 4 As the importance of holy relics increased, cathedrals and monasteries developed. Many people struggled to initiate Christian ideology in politics and religious arenas and pilgrim culture became much more popular. Medieval pilgrimage was oftentimes deeply related to religious hegemony and authority. As Peter Brown pointed out, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1995). 2 J.N.D. Kelly, Jerome: His life, Writings, and Controversies (New York: Harper & Row, c1975), 91-103. 3 Especially, Peter Walker, “Pilgrimage in the Early Church,” Craig Bartholomew & Fred Hughes eds. Explorations in a Christian Theology of Pilgrimage (Aldershot, Hants, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004), 73-91. 4 Patrick Geary, Furta Sacra: Thefts of Relics in the Central Middle Ages (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, c1978). 3 ‘the dead saint’ remained still powerful among medieval Christians.5 Medieval pilgrimage helped to shape Christian liturgy and town culture based upon such traditions.6 Pilgrim culture was developed further in Carolingian Christianity, especially in the time of Charlemagne the Great. As we see in the fourth Lateran council in 1215, pilgrimage was clothed in theological hermeneutics such as the means of the punishment of sin and grace of God. The pilgrims also provided useful labors by carrying stones and wood for their own repentance. In the high middle ages, northern Europe became the center for medieval pilgrimage. Rome still remained an international pilgrim center. Islamic threat, however, forced medieval Christians to find alternative but safe pilgrim centers, to replace Jerusalem and Constantinople. Pilgrims from France and northern European countries sought other pilgrim centers so that they could avoid the cold and dangerous route through the Alps. For this reason, Compostela, “Field of Stars,” emerged as a new international pilgrim center. The fact that diverse new national pilgrim centers arose during this period shows the rapid development of pilgrim culture. Trier, Köln, and Mainz Germany, Einsiedeln, Switzerland, and Walshingham, England, attracted not only national but also international travelers. The power of pilgrimage, a living icon for medieval Christians, was a stronger force than that of intellectuals and theologians. The power of pilgrimage, which ‘the dead’ moves ‘the living,’ continued to the end of Middle Ages. The critique of Luther and Calvin against ‘immoral and unreasonable pilgrimage’ paradoxically witnesses to the dominant power of pilgrimage. 7 Even though medieval Christianity eventually dwindled as time went on, the popularity of pilgrimage still ran through the Reformation period. Medieval pilgrimage was deeply related to the development of medieval towns. Some good examples of this are St. Mark’s Cathedral in Venice and St. Denis’s Cathedral in Paris. They show how martyrdom, pilgrimage, and the development and expansion of towns are closely interrelated. Increasing numbers of pilgrims resulted in the expansion of pilgrim centers, and along with them, medieval towns drenched in Christian culture could develop gradually but widely. James Howard-Johnston & Paul Antony Hayward eds., The Cult of Saints in late Antiquity and the Middle Ages: Essays on the Contribution of Peter Brown (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1999). 6 Dee Dyas, “Medieval patterns of Pilgrimage: a Mirror for Today?,” Explorations in a Christian Theology of Pilgrimage, 92-109. 7 Graham Tomlin, “Protestants and Pilgrimage,” Explorations in a Christian theology of pilgrimage, 110-125. 5 4 Medieval pilgrimage was related with the development process rather than with the origination and formation of towns. Shaped out of traditional villages and towns in the beginning, many towns depended on holy relics rather than the pilgrims. Translation. and acquisition of the relics provided a religious authority and justification for a new cathedral and monastery. Saints did not move, but the pilgrims who sought saints moved and stimulated the development of towns. People gathered, markets formed, information was shared, and religious symbols and social developments intermingled. While discussing the journey to Compostela, one of three major pilgrimages, I would like to pursue the relationship between pilgrim culture and the development of the town, and try to add a certain Christian interpretation to it. II. Christian Pilgrimage and Towns II-a) Towns on the Way to Pilgrimage With the emergence of Charlemagne and Carolingian Christianity, France became the major center of medieval Christianity. Tension and competition between France and Italy did not simply result in the Avignon Captivity (13141362). Confronting an Islamic expansion and confusion and instability after Reconquista, France eventually expanded her power toward Italy over the Alps and toward the area of northern Spain. The attraction of two international pilgrimages -Jerusalem and Rome- especially Rome, nevertheless, was not radically reduced. In this situation, however, Santiago de Compostela, “Field of Stars” in north-western Spain came to the front as a pilgrimage destination. The passage to Compostela originally began from four major places within France: Paris, Bezlay, Le Puy, and Arles, and also ran throughout most of the French territory. Compostela had many merits. It was much closer to travel to from French territory but could provide foreign experiences for the pilgrims. Many people well understood the reputation of the Spain Crusade and were familiar with literature like The Song of Roland. The Compostela cathedral itself and Cluny, the most powerful international network at that time, were other contributors to the flourishing of pilgrimage. Liber Sancti Jacobi Book V, which contained useful information for the pilgrims to Compostela, provided various indexes of holy relics and saints 5 scattered around the Europe on the way to Compostela.8 This document shows that people from as far away as Scandinavia and England also visited Compostela. The enthusiasm of European Christians for traveling toward Compostela did not cool down for a long time. Even though St. Denis was a legendary holy place in northern France where many royal families stayed, for many reasons, people continuously sought the journey to Compostela. Even though Compostela was the final destination, however, it is important to know that there were numerous “towns on the way” which were required to support the pilgrims’ travel. For the commoners who had difficulty traveling, national or regional pilgrim centers would have also been attractive. Many pilgrim centers and towns emerged quite naturally along the way to Compostela as resting and eating locations for pilgrims and their animals. Bezlay, one of four major staring points to Compostela, is a good example of this. Bezlay is loca sancta where the holy relic of the body of Mary Magdalene is enshrined on the hill. Mary broke the perfume jar and poured it over the head of Jesus at the house of Lazarus. After the ascension of Jesus, Mary Magdalene traveled with Maximinus, another disciple of Jesus, to Marseilles, and after that died at Aix. Later on, Badilon, a monk, moved her body to Bezlay. The fact that Bezlay looks like a ship ready to take a voyage to the west, seen from the east, was enough to inspire the people to leave for Compostela. Bezlay was under the great influence of Cluny who had authority over “the Milky Way”in northern Spain. Bezlay was also the place where Bernard of Clairvaux preached to support and to encourage the second crusade. In spite of its small size, Bezlay had a huge impact on neighboring areas because of its many pilgrims. Four pilgrim routes that originated in France were united in Puente la Reina, in north-eastern Spain. Three routes from Paris, Bezlay, and Le Puy, were united in St. Jean-Pied-de-Port. These three ‘holy routes,’ and the fourth, a route from Arles, were brought together in Puente La Reina, in Spain. Although Puente was smaller in size than Pamplona, it became more famous because pilgrims from four different routes met together at this town. As it developed rapidly due to pilgrimage, the wife of Shancho III, king of Navarre, helped to build the Queen’s Bridge in the eleventh century. DO WE KNOW HER NAME? She wanted to protect the pilgrims by building the bridge, and to secure the stability and development of the towns. The Milky Way was the route from Puente to Compostela approximately 800 William Melczer, The Pilgrim’s Guide to Santiago de Compostela (New York : Italica Press, 1993), 84-133. 8 6 kilometers along country roads and through numerous towns Although the pilgrims shared the simple fact that they were “on the way,” however, it was evident that they had many differences in their goals of pilgrimage, language, personal background and social status. A record tells us that many commercial buildings filled the main streets of Puente.9 In addition, we can see the diversity in races, language, and even in the structures of towns. For example, the towns surrounded by walls had a large Franco area in the late eleventh century, and also there was a small quarter for Jews. The people usually spoke Navarran, a Spanish dialect, but they used various languages including French, Hebrew, and Basque. There were even two and three-story buildings in towns which flourished. In 1142, the templar knights began to have authority over Puente and they and many other religious institutions began to run hospices to provide free beds for the pilgrims. To guide the pilgrims in late evening, they rang a bell forty times from around nine to ten o’clock. Interestingly, we know that there were many thieves, and Jacques de Troya was executed in 1350. II-b) Holy Turning Point: Compostela Compostela began to function as a major pilgrim center in the ninth century and reached its peak in the twelfth century when about a half million pilgrims visited each year. Located far away from ferocious Islamic power, Compostela provided a safe international pilgrim destination for northern Europeans. Compostela was a turning point for lengthy pilgrimage, and also showed the peak of the pilgrim culture. The process and a series of rituals that the pilgrims used to keep when they entered the city and cathedral provide a good case study of medieval pilgrim culture. 10 We have more documents and materials from Compostela than any other place in Spain. The relationship between pilgrimage and the development of towns, the main argument in this paper, is well uncovered on the way from Puente to Compostela. The lengthy route of this pilgrim journey was able to unite northern Spain in economic and religious aspects, and also contributed to development of numerous towns.11 The process by which Compostela emerged as an international pilgrim center from the ninth to the twelfth centuries portrays symbolically the relationship between the towns and holy relics, interaction of religious factors and political David M. Gitlitz & Linda Kay Davidson, The Pilgrimage Road to Santiago: the Complete Cultural Handbook (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2000), 82. 10 Mary Lee Nolan, Christian Pilgrimage in Modern Western Europe (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, c1989). 11 Victor Witter Turner, Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture: Anthropological Perspectives (New York: Columbia University Press, 1978), 172-202. 9 7 circumstances, and correspondence between legends related to martyrs and formation of the texts. The importance of Compostela came from the fact that the relic of St. James was enshrined here. The fact that James was one of the core disciples of Jesus (along with Peter, Andrew and John), and the rumor that the most complete holy relics of James remained there, made Compostela the most charming pilgrim town for medieval Christians. James, the son of Zebedee, preached the gospel after the passion of Jesus, and it was believed that he was persecuted by Herod in 44 AD. As is seen in Passio Jacobi (Passio Jacobi in the fifth century, or Dei verbum patris Ore proditum), the story of the life of James –even though it was not always clearcame to the stage in conjunction with the Spanish mission. From a fairly early period on, it was believed that the relics of James were venerated in Compostela. But it was only in the ninth century when people discovered the tomb of James that they made him the patron saint of Compostela. Bishop Theodemir of Iria Flavia discovered the tomb of James in a miraculous way by the guide of Campus Stellae.12 Being discovered when the Reconquista had just begun, the tomb of James became the religious and spiritual landmark for this area. When Diego Gelmirez (1073-1078) was promoted to arch-bishop and initiated the construction of cathedral (completed in 1211), Compostela became a more stable and famous pilgrim center.13 It also consolidated its international reputation with strong support from Cluny, one of the most powerful Christian institutes. The most valuable document in understanding the development and interaction between pilgrimage and towns is Liber Sancti Jacobi. Among the five sections of this book, the fifth part contains the most useful information for the pilgrims.14 Of course, “The Pilgrim’s Guide,” the fifth part of this book, is not a detailed guidebook, but provides overall information for the pilgrims. Nevertheless, this book is valuable in three aspects. First, it contains concrete information as follows: general routes, motives, geographic information, possible dangers on the way, and the needs of everyday life like money exchange. Second, it describes major facilities in towns such as hospitals and clinics, hospices and lodges, monasteries and other useful facilities. Those 12 “The Origin of the Cult of St. James of Compostela,” Jan van Herwaarden, Between Saint James and Erasmus (Brill, 2003), 311-354. 13 Edwin Mullins, The Pilgrimage to Santiago (New York: Interlink Books, 2001), 206-213. 14 Debra A. Birch, “Welfare Provisions for Pilgrims in Rome,” Pilgrimage to Rome in the Middle Ages, 183-16). “The Integrity of the Text of the Liber Sancti Jacobi in the Codex Calixtinus,” 355-375. *website sources:www.humnet.ucla.edu/iagohome, www.humnet.ucla.edu/roncpoem. 8 factors were crucial not only for personal use but also for the development of towns. Third, it also portrays gestures and actions expected from the pilgrims when they arrived at Compostela. Compostela symbolized the completion of the pilgrimage but was also the half -way turning point for the pilgrims. Even though it was small in size compared to many European towns, Compostela grew at a great speed primarily because of its reputation as an international pilgrim center. “The Pilgrim’s Guide” says that Compostela had 7 gates and 10 churches within the town boundary. The French-style Basilica of St. James was ostentatious and majestic to charm the eyes and minds of pilgrims who came from far away. Window glasses and many sculptures on the upper part of the main gates drew strong feelings of piety and faith for many people. The quality of water from the Basilica was far different from the polluted and contagious water on the way. Water within Basilica was “sweet, nourishing, healthy, clear, excellent, warm in winter and fresh in summer”.15 It was not only a place for spiritual consolation. Markets were in the front yard of Basilica. They sold sea shells, and mended sandals, pouches, and belts. People also purchased medications and medicinal herbs there. At other street markets within a short distance, people could meet many merchants who dealt with money exchange, lodging, etc.16 Compostela did not simply attract pilgrims from every corner of Europe. As C. Rudolph mentioned, the pilgrimage to Compostela was instrumental “in the reintegration of Christian Spain into the European community, the development of international trade, the internationalization of monumental architecture and sculpture, and the re-conquest of Moorish Spain.”17 Many towns on the way to Compostela and the holy turning point in Compostela were central for “spiritual pilgrims.” Compostela was developed with the help of many other towns on the way. For example, St. Leonard on the way to Compostela was one of the busiest towns, but it was almost unknown and much less crowded before the eleventh century. Based upon a document written in 1121, Jonathan Sumption wrote that no one thought that that town was more crowded than any other Spanish town. 18 These towns could not have been so developed before Compostela emerged as a well-known international pilgrimage. Pilgrim’s Guide, 122. Pilgrim’s Guide, 122-123. 17 Conrad Rudolph, Pilgrimage to the End of the World: the Road to Santiago de Compostela (Spain, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 4. 18 Jonathan Sumption, Pilgrimage: An Image of Mediaeval Religion (London: Faber & Faber, 1975), 163. 15 16 9 II-c). Pilgrimage and Development of Towns The primary meaning of ‘pilgrims’ is ‘people on the way.’ Pilgrimage emphasized mobility and dynamics rather than stability and inclination to settle down which holy relics tend to have. What attracted people to pilgrimage and made the people move continuously, however, were saints, cathedrals, and necessary facilities like lodges and charitable institutes. Likewise, pilgrim culture and towns were inseparably related each other. Dian Webb shows that pilgrimage is closely related to politics, economics, and culture in general. 19 The journey from Bezlay to Compostela was carried out via many towns. Iter Jacobi divided a lengthy journey from Pamplona to Compostela into 13 days mostly following major towns. A few issues below will illuminate the relationship between pilgrimage and these towns. Saints (Translatio, reliqua) The acquisition of the relics of saints was the primary motive for pilgrimage and the foundation of city development. Holy relics, once enshrined, did not “travel” (move), but the pilgrims continuously moved.20 This was the principle for regional and international relics. Holy relics had a huge impact on the establishment and dramatic development of medieval towns. The more they acquired famous relics, the more they attracted the pilgrims, and consequently this reflected the influence of the towns and their financial power. They could expand markets by acquiring the relics and exhibiting them (ostensiones) especially on feast days. The reputation of Bezlay, never falling behind compared to Fontenay, the most conspicuous monastery at that time, came from the fact that Bezlay had the holy relics of Mary Magdalene. We can find a similar example in the history of St. Mark in Venice. The translatio itself of holy relics had absolute authority and power over the towns. The ritual of translatio drew many pilgrims and quite naturally formed a large market. Köln was significantly developed when they acquired the relics of Three Magi in 1164. When the relics of Three Magi came to Köln, a major departure center for Compostela, the emperor Otto IV donated a large sum of gold and treasure to that city. Lords and bishops preferred to have meetings at the places where the relics were enshrined. Political and religious authorities used this chance to enhance financial profit and political stance. “The Pilgrim’s Guide” mentions in detail major cathedrals from St. Triompius 19 20 Diana Webb, Medieval European Pilgrimage (New York: Palgrave, 2002), esp. pp.114-115. J. Sumption, Pilgrimage, 40. 10 to St. James on the way to Compostela.21 About 45% of the Book V contains the story of holy relics, saints, and pilgrimages, which in turn shows the importance of the saints and relics. In this process, the authenticity of holy relics was crucial in recruiting the pilgrims and developing the towns. When the authenticity of Bezlay’s relics was threatened later on, the number of pilgrims drastically declined, and consequently food trade and other commercial circumstances suffered. The Pilgrims to this town, the original place for the second crusade, radically decreased due to the wars and taxes.22 Miracles, Religious Symbols and Phenomena The place where holy relics were enshrined flourished with many miracle stories, healings, and other mysterious events. The religious authority of holy relics was in proportion to the frequency and density of miracles. Miracles also played a medical function. Religious phenomena and symbols including miracles helped the pilgrims decide the route and period of their stay. Religious vision and imagination strengthened the religious function of the towns where the relics of the saints and religious traditions were kept. Various stories of saints in ‘The Pilgrim’s Guide’ added to the travelers’ religious imaginations and symbols, and they served to draw more pilgrims. Miracle stories at Walshingham made that place an internationally-known pilgrim destination. Lavamentula (a symbolic ritual to clean the secret part of each pilgrim) was a very important religious symbol when they came to the cathedral of Compostela. Managing Cathedrals and Financial Expansion As there were numerous cathedrals in medieval towns from Paris to Rome, there was a cathedral in each pilgrim center as well. Monastery chapels scattered around Europe played a similar role to cathedrals. Cathedrals improved the spirituality of believers and pilgrims, and were also foundational for the development of the towns. Gothic cathedrals and monasteries in the twelfth century received donations not only from the rich upper class but also from day laborers. Cluny, the most powerful sponsor for the Compostela pilgrimage, emphasized liturgy and supplication. The long list for prayer was primarily related to offerings and donations of the pilgrims Pilgrims labored as a means of penance and grace, which was another stepping stone for the economic development of cathedrals and monasteries. Cathedrals had other economic means by which to enhance their economic 21 22 Pilgrim’s Guide, 96-118 J. Sumption, Pilgrimage, 45-46. 11 development. As I mentioned above, pilgrim towns made a lot of economic profit when there was translation of relics or a jubilee year when all sin was annulled publicly. In spite of the general assumption that holy relics did not travel, it appeared holy relics were a tool for economic profit. As Birch asserted, ‘relic pilgrimage’ which was carried out by the pilgrims brought the people a huge economic profit.23 Not a few pilgrims sold relics clothed with vision and imagination they designed. The pilgrims sold not only public souvenirs but also souvenirs they stole. The churches prohibited this secular business, but they did not hate the economic profit it brought to the church and towns. The cathedral of Compostela (The Capilla Mayor), the most conspicuous Romanesque building in the twelfth century, shows this relationship between holy relics and economic advantage. The cathedral kindly explained the fact that the pilgrims to the Basilica of St. James could send a certain cloth based upon individual faith and finance. The fact that this book contains detail about the size and length of the altar cloth for decoration tells that many people used to donate valuable things. It must have been of great help to cathedral finance. Medieval cathedrals had significant power over neighboring lands and forests, and they also made a lot of profit out of special permission to trade and tax the goods. However, cathedrals did not simply make economic profit for their own advantage. The Compostela cathedral used the offering from Palm Sunday to Easter Sunday for the pilgrims at Compostela. A tenth of all offering at the altar of St. James was used for the hospice. Free lodging was given to the pilgrims at the altar of St. James out of this offering, and extra care was given to the weak, and also special help was provided for the lepers to walk up to the altar on Sunday. 24 The Cathedral at Romacador suffered a huge loss because of the great drought in 1181.25 It is certain that offerings and donations of the pilgrims contributed to the development of the towns. Length of Journey People visiting regional pilgrimage sites did not have much need to prepare. When an international pilgrimage like Compostela was their final destination, however, there would be many preparations including finding information about the length of travel, lodging, food, clothing, etc. Some people even wrote a will Debra A. Birch, Pilgrimage to Rome in the Middle Ages: Continuity and Change (Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK; Rochester, NY: Boydell Press, 1998), 183-16. 24 Pilgrim’s Guide, 131-132. 25 J. Sumption, Pilgrimage, 235. 23 12 in case they could not return to their homeland. What were the lengths of travel in Northern Spain? ‘The Pilgrim Guide” estimated 3 days from Somport to Puente, and 13 days from Cisa Pass to Compostela (375 km in a straight line). But it was almost impossible to travel from Pamplona to Burgos within 2 days, which was 106 miles in a straight line. Although there was a shorter way to travel in a day, this book also provided other routes that the pilgrims could travel by horse. Distances and times suggested in the Guide were calculated simply based upon traveling by walking. However, it was not an easy job to travel 800 km in 16 days, 50 km on average walking every day. It seems unnatural for the pilgrims to walk 50 km everyday only after staying one day even when that sort of international journey could be only once in their lives. In this context, I think the Guide only estimated distance and time for approximate traveling. Norbert Ohlers provides another calculation for traveling.26 He estimated that a walker would travel 15-25 km a day, or for any traveler on a horse to travel 20-30 km a day. A recent travel Guide, after calculating 25 km (5-8 hours depending upon the travelers) suggests 33 days from Navarra to Compostela.27 Even this calculation came from assumption that each pilgrim traveled following a plain route. But we should remember that Ohler’s calculation might be misleading when considering unexpected hazards and dangers, and the time for traveling might be doubled or tripled in the Middle Ages. Because of numerous pilgrim centers and ‘spectacles’ on the way, it would take several weeks to several months. People did not only choose the land route for internationally well-known pilgrimage. Just like Venice where many ships embarked to Jerusalem, a port was a big help for the pilgrims. Some people from Scandinavia, England, and Scotland used a sea route to national and international pilgrim centers.28 It is also important to know that there was another pilgrim route following the beach in northern Spain, which ran parallel to the inland route. Although there was some disadvantage in traveling by ships in not visiting any other pilgrim centers, it could be much cheaper and faster than land routes. Of course, the towns at the departure and destination of pilgrimages benefited. Lodging Lodging was the most important necessity for the pilgrims. The pilgrims Nobert Ohler, The Medieval Traveller (Trans. By Caroline Hiller, The Boydell Press: UK, 1989), 97-101. 27 John Brierley, A Pilgrim’s Guide to the Camino de Santiago (Findhorn Press Ltd. 2006). 28 Webb, Medieval European Pilgrimage, 118. 26 13 needed lodges to avoid the wind, get medical care, and get religious rehabilitation. There were three different facilities for the travelers. First, there were monastery facilities following the Benedictine rule. The monastery, the house of God and holy place, ran hospices and provided a simple but necessary rest and a peaceful atmosphere. Second, there were charitable hospices run by specific institutes, churches, knights, and village communities. Tents were furnished with a bundle of straw for a bed. But most could not provide enough food except the rich cathedrals. At the most well-equipped hospice, the pilgrims could get eggs, cheese, bread, and a little marinated meat. The pilgrims were satisfied to warm up their bodies and escape the cold. They could mend their clothing and sandals. ‘The Pilgrim’s Guide’ gives a compliment to the hospice at Santa Christina, on the way to Northern Spain. God has, in a most particular fashion, instituted in this world three columns greatly necessary for the support of his poor, that is to say, the hospice of Jerusalem, the hospice of Mount-Joux, and the hospice of Santa Cristina on the Somport Pass.29 This hospice had beds and food for travelers, clinics, shelters for the animals, and some space for money exchange. The Guide calls this hospice a ‘holy place.’ Here the hospice helped pilgrims recover, consoled the patients, and buried the dead. Santa Christina showed well how pilgrimage and the towns on the way were deeply related. For example, when the monks at Saint Christina moved to Jaca in 1569, the function of various facilities including charitable hospices was far reduced. Consequently, the overall function of the town ground to a halt. Third, there were inns, the most common lodging. On the way to Rome in the fourteenth century, for example, there was an inn every two or three miles. Although these lodging facilities were for economic profit, owners of the inns would take care of the week and feeble, protected the pilgrims, and helped with their basic needs. Owners of the inns pursued economic profit, but theoretically at least, they would treat all the pilgrims as miles Christianus. All of these hospices and lodges were connected with the economic development of the towns. Trading and Circulating in Market: Holy Utensils, Souvenirs, Information 29 Pilgrim’s Guide, 87. 14 Saints and religion were the primary motivators for pilgrimage. When it came to an international pilgrimage, however, a religious vision was not simply enough. From finding a room for overnight to securing a boat to cross a river, oftentimes at the risk of their own lives, it was not easy for the pilgrims. The contentious and puzzling encounter between religious ideals and the realities of life could be felt not only ‘on the way’ but also at each ‘town’ the pilgrims passed through. During the stay of the pilgrims in the towns, the market was very important. Markets were the places for money exchange, purchasing souvenirs, and acquiring and circulating information and news. The churches and monasteries were frequently involved in licensing, taxation, real estate, and also the markets. This meant that pilgrimage and the market were developed side by side. Unlike the ‘sacred atmosphere’ inside cathedrals and chapels, liveliness and confusion described the markets. Arculf, who traveled to Jerusalem, found Jerusalem filled with a bunch of pilgrims and wrote that “there was by custom a great buying and selling in the City, and crowds of people, camels, horses, and donkeys, with the result that the streets of the bazaar were in a terrible state.”30 This sort of confusion was common in the towns where the pilgrims gathered. Cathedrals were usually located at the center of the towns, and there was a large market in front of the cathedrals. In this sense, the major place for pilgrimage and the market were closely related in terms of geographical and functional aspects. As we can see in Bernard Angers, Conque, in the eleventh century, the saint feasts of the church were also related with the market. In a feast day when the church proclaimed indulgence, the entire town became a marketplace. The towns formed a market to provide the necessary facilities for the pilgrims, and the market was important factor for the stability and economic development of the town itself. Money exchange, purchasing any item for worship and offering, trading souvenirs including badges and hats, contributed greatly to the economic development of the markets. Markets were a common link between ‘sacred’ and ‘profane’ worlds. In the markets, the pilgrims purchased daily necessities, holy utensils and instruments, and souvenirs. On the way to Jerusalem, Rome, and Compostela, the pilgrims tried to purchase anything that contained a sort of ‘the sacred’ from a part of holy relics of the saints, holy water and oils, and even dust and soils. These items were not simply bought as a sort of ‘hobby’, but they seemed to have a kind of magical charm. The pilgrims preferred to have a E. Moore, The Ancient Churches of Old Jerusalem: the Evidence of the Pilgrims (London, Constable, 1961), p.20. 30 15 little water jar which could contain water or oil. The commoners preferred cheap and fragile utensils, paper, and badges to any luxurious items. This preference was commonly found both on regional and international levels. The trading and circulation of rather cheap but fragile souvenirs showed a certain relationship between pilgrimage and towns. Churches and secular authorities were involved in manufacturing and trading the silver badge and shell badge. But it was handicraftsman that actually made those items. As Webb’s analysis on Rocamador shows, a certain conflict between handicraftsman and the Dominican monks was brought out regarding the right of manufacturing and trading.31 Even merchants stole the items secretly without permission and sold them again for profit. Sometimes the economy of a certain town depended on this illegal trade. Trading of particular sea-shells and badges was popular in Compostela. In early times, the pilgrims collected sea-shells on the beach by themselves. In 1120, however, sea-shell trade began on a commercial level. We know that after 1200 not a little financial profit came out of the licensing of various souvenirs. A bishop in Rugo, a neighboring town of Compostela, sold such souvenirs without any formal permission of the Compostela cathedral. They got a substantial economic profit out of trading.32 In the market, stories were often traded for profit. A ‘professional pilgrim’ appeared to visit the pilgrim centers repeatedly to make money. They sometimes spread a story or rumor they had collected on the way, and also amplified the story for the common pilgrims. Sometimes, they repeated the story again and again in public places to have the purse of fellow pilgrims opened.33 Even though ‘The Pilgrim’s Guide’ provided useful information for pilgrimage, as Webb argued, it was not easy to acquire and circulate overall information on pilgrimage. When it came to an international pilgrimage, it was far more difficult to get any relevant information on route, direction, and lodging. For this reason, as the Guide indicated, people from the same towns or areas or guilds traveled together. It is interesting to see that the concrete need of the pilgrims was deeply involved with the economic development of the merchants. Merchants were under the same rules and regulations as the pilgrims from the church and secular authorities, because the merchants traveled peacefully without any military arms. Such merchants had much information on boats, ships, horses, Webb, Medieval European Pilgrimage, 35. J. Sumption, Pilgrimage, 248; Cynthia Haen, “Loca sancta souvenirs: Sealing the Pilgrim’s Experience,” Robert Ousterhoust, The Blessing of Pilgrimage (1990), 85-93. 33 Howard Loxton, Pilgrimage to Canterbury (Newton Abbot: David and Charles, 1978), p. 96. 31 32 16 hospices, and inns. For this reason, the information merchants collected meant ‘money,’ 34 and circulating and trading information and knowledge meant economic activity for profit. As we see in the merchant of Conques in the eleventh century, some people took a more active response, from an economic perspective, to the endless pilgrims. Several guilds accompanied the pilgrims together, or sponsored certain expenditures of the pilgrims, and even some guilds changed the name of their towns following prominent pilgrim centers.35 Some people who belong to the ship guild made a ship model out of metals and silver, and they sold them to the pilgrims. Likewise, we can see a number of cases that revealed mutual development and inter-dependence between towns and pilgrimage. Pilgrim, Towns, Economy, Relationship with International Religious Institutes As Teofilo F. Ruiz pointed out, many people left their homes to pursue an economic profit along the pilgrimage route. Development and growth of Logrono, a major town to Compostela, provided a model for many towns that depended upon pilgrims. Unlike the towns in rich coast of northern Spain, Logrono, secluded and heavily dependent of the pilgrims, primarily produced and traded wines. A neighboring town, Burgos, was less depended on the number of pilgrims. After 1250, the wine trade of Logrono was strongly challenged by neighboring villages and the towns in southern France. As the number of the pilgrims decreased in the later medieval ages, the town of Logrono was drastically weakened. 36 Logrono was in a difficult situation by competing with Aragon, Navarre, and Castilla. In addition, some towns forcefully changed the pilgrim route to satisfy their own economic profit. In 1168, Ferdinand II, Castile, blocked a traditional pilgrim passage and opened a new way to attract more pilgrims to Leon where his precedent Ferdinand I was enshrined. It shows how important pilgrimage was to a town’s economy, regardless of its size. After Charlemagne’s war of expansion in northern Spain, the friendly relationship between Spain and France continued in Compostela and Cluny. In fact, ‘The Pilgrim’s Guide’ itself reflected the influence of Cluny. The friendly relationship was strengthened by Alfonso VI (1065-1109), a monk of Cluny who became the bishop of Compostela in 1094. Cluny began to have the most powerful political and religious authority after the tenth century. The religious Webb, Medieval European Pilgrimage, 108. Webb, Medieval European Pilgrimage, 109. 36 Teofilo F. Ruiz, „Merchants, Trade, and Agriculture,” in Crisis and Continuity, Land and Town in Late Medieval Castile (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, c1994). pp.220223. 34 35 17 and symbolic power of Cluny was a good partnership for Spain when the people wanted a religious cause and justification for pilgrimage. In this context, Sancho III (Navarre) donated substantial money to Cluny for nine years. Cluny supported towns and pilgrim centers on the way to Compostela. Further development in areas of arts, culture, and architecture in the towns of southern France and northern Spain was possible because of this mutual support. In the cathedrals of Leon and San Isidore, we see how the development of towns and ideals of pilgrims converged. Leon cathedral, the second reconstruction done in 1084, had already run hospices for the ill and the poor. The third reconstruction was done in grand Romanesque style, and it showed its political and religious status. Reconstruction into Gothic style after Rheims cathedral in 1205 was possible because of its tie with politico-religious leaders including the pope and major religious institutes. It also uncovered how cathedral leaders recruited artisans and pilgrims to complete the construction. Basilique Ste-Madeleine in Bezlay, one of the most outstanding examples of Romanesque architecture, was successful because of the economic support of Cluny. The journey of pilgrimage to Compostela in French territory was influenced by the seasons. Spring and fall were good for traveling. On the way to Compostela, they could have a chance to look at various types of architecture, sculptures, pictures and paintings, and metal arts, and could be inspired by music and poetry. In the case of international pilgrimage, people made a group out of various guilds for traveling. Group traveling was useful to avoid any possible dangers they could face on the way. The Guide criticized tax collectors and ferry boatmen for their ferocity and immoral acts. The law allowed profit-driven merchants to pay the fee to pass the national or regional boundaries. But illegal tax collectors exploited the pilgrims by taking passage-tax with cash, oftentimes double or triple than habitually required. The Guide claimed that ferry boatmen could collect the fee from the rich traveler or horses, but not from the poor pilgrims. In fact, however, they loaded as many as people as possible, and once the boat turned over, they sought out the pockets of the dead to exploit them of their money.37 II-d) Encounter between Towns and Pilgrims: From Solidarity to Understanding The relationship between towns and pilgrimage was deeper than superficially 37 Pilgrim’s Guide, 91-93. 18 observed. Based upon material and social grounds, the pilgrims developed the concept of solidarity and communication. The pilgrims gathering around the village and towns built up mutual solidarity . In addition to the permanent residents in towns, there were temporary pilgrims who stayed only for a short period of time. In Bezlay, many people stayed for a long time until they had gathered enough people for long-distance traveling or until they could celebrate a certain feast together. It was same in Puente la Reina which was the first major spot in the Milky Way to Compostela. In major or important towns, people waited long to find fellow travelers and companions, like a ship that waited for enough material for her voyage. ‘On the way,’ there were many ‘little saints’ who charmed the pilgrims. Sometimes, regional pilgrim centers were competing with international pilgrim centers. Viabranca del Bierso grew after people agreed to claims that once the pilgrims properly performed pilgrims’ rituals there, they could get religious compensation even if they did not go on to Compostela. Once they agreed to this proposal, they did not need to go to Compostela, and consequently they could save money and time. What is important here is that solidarity grew up among the town inhabitants and the pilgrims to the towns. What Turner labels as not ‘uniformity’ but ‘unity in diversity’ was deep seated among the pilgrims and strangers.38 In a feudal society and country towns where encounters and meetings were rare, there was not much solidarity among the ‘strangers.’ In a large village or town, even though they seemed heterodoxy as seen from the outside, the pilgrims came together under the same umbrella of Christianity and pilgrimage. The term landsmannschaft for the German pilgrims originated from the group concept of the pilgrims. In addition to this religious-social solidarity, many people used pilgrimage as a process of repentance and reward. People in towns began to form official standards and unification of the religious norms and rules. In this sense, we can say that the development of pilgrimage happened side by side with the development of liturgy and the norms of the churches. Many pilgrims from different origins and backgrounds spread a certain standardized guideline beyond geographic boundaries which finally produced solidarity. This also caused the people to change their understanding of pilgrimage. In this context, Dee Dys stresses that the concept of pilgrimage changed from mobility (place- 38 Victor Witter Turner, Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture, 190-192. 19 focused) to interior pilgrimage (inward-status focused).39 The formation of mutual solidarity brought out the issues of mobilitas and stabilitas. Pilgrims were primarily developed ‘on the way’ (peregrinatio) out of ‘stability.’ The stability also produced dynamics and change in each town. Each town on the way was not simply ‘inn’ for lodging and food. Bezlay and Compostela were not simply departure or holy turning points. When looking at the lives of the pilgrims in the towns, the concepts of mobility and stability are easily recognized. In towns, we can find prejudice, conflict, and compromise. Just like the pilgrims had different intentions, the people within the towns were fairly different. In the towns, the pilgrims experience the full range of prejudice and difference. 40 When ‘standard Christianity’ was not rooted in Europe yet, mutual understanding of the pilgrims was filled with prejudice and mistrust. There were cultural and religious differences. As we see in Bezlay, the problems of acquiring lodging and daily necessities evolved into class struggles. The circumstances of the royal family were quite different from that of the commoners. As we know from The Cloud of Unknowing, certain conflict and critique continued to the end of the medieval period. In towns, there was a certain common indicator that could overcome all the differences. For example, holy relics of the saints harmonized and modulated all the difference in language and culture. The pilgrimage originally begun with a religious motif went far beyond the division and conflict between sacred and profane, (individual) body and society, subject and object, even male and female.41 With the help of saints, different pilgrims could experience ‘positive contagion’ and ‘homogeneity’ among themselves. It was in town, in the public sphere that this contagion worked. We can see another good example in the Mendicants of the thirteenth century. Mobility and inter-penetration of pilgrim culture contributed to make a common denominator for northern Europe. IV. Conclusion: Pilgrims in Towns, Development of Towns in Pilgrimage There have been many previous works that attempted to find religious meanings and interpretations of pilgrimage. The study of pilgrimage itself would be a fascinating topic. However we do not have enough previous study on the “Medieval Patterns of Pilgrimage,” Exploration in a Christian Theology of Pilgrimage, 92101. 40 J. Eade, “Christian Ideology and the Image of a Holy Land,” Contesting the Sacred: the Anthropology of Pilgrimage (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000), 98-121. 41 S. Morrison, Women Pilgrims in Late Medieval England: Private Piety as Public Performance (London; New York: Routledge, 2000), 4. 39 20 relationship between towns and pilgrimage. It is not easy to make any statistic theory about this relationship. I hope this paper provided a little stepping stone for further study. As religion exists in the world, pilgrimage will continue. It is just as Chaucer wrote a long time ago: When April with its fragrant showers the drought of March has pierces to the root… When the West Wind with his sweet breath has breathed life into the new shoots in every wood and field… And small birds make melody… Then people long to go on pilgrimage… (…) At night there came into that hostelry Full nine and twenty in a company Of carious sorts of people, fallen by chance Into fellowship and pilgrims were they all.42 References Birch, Debra A. Pilgrimage to Rome in the Middle Ages: Continuity and Change (Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK; Rochester, NY: Boydell Press, 1998) Brierley, John. A Pilgrim’s Guide to the Camino de Santiago (Findhorn Press Ltd. 2006). Coleman, Simon & John Elsner. Pilgrimage: Past and Present in the World Religions (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1995). Dyas, Dee. “Medieval patterns of Pilgrimage: a Mirror for Today?” In Explorations in a Christian Theology of Pilgrimage (Aldershot, Hants, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004), 92-109. Eade, J. “Christian Ideology and the Image of a Holy Land.” In Contesting the Sacred: the Anthropology of Pilgrimage (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000), 98-121. Geary, Patrick. Furta Sacra: Thefts of Relics in the Central Middle Ages (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, c1978). Gitlitz, David M. & Linda Kay Davidson, The Pilgrimage Road to Santiago: the 42 Chaucer, General Prologue to the Canterbury Tales, 1394. 21 Complete Cultural Handbook (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2000). Graham Tomlin, “Protestants and Pilgrimage.” In Explorations in a Christian Theology of Pilgrimage, 110-125. Haen, Cynthia. “Loca sancta souvenirs: Sealing the Pilgrim’s Experience.” in Robert Ousterhoust, The Blessing of Pilgrimage (University if Illinois Press: Chicago, 1990), 85-93. Herwaarden, Jan van. Between Saint James and Erasmus (Brill, 2003). Howard-Johnston, James & Paul Antony Hayward eds. The Cult of Saints in late Antiquity and the Middle Ages: Essays on the Contribution of Peter Brown (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1999). Kelly, J.N.D. Jerome: His life, Writings, and Controversies (New York: Harper & Row, c1975). Loxton, Howard. Pilgrimage to Canterbury (Newton Abbot: David and Charles, 1978). Melczer, William. The Pilgrim’s Guide to Santiago de Compostela (New York : Italica Press, 1993). Moore, E. The Ancient Churches of Old Jerusalem: the Evidence of the Pilgrims (London, Constable, 1961). Morrison, S. Women Pilgrims in Late Medieval England: Private Piety as Public Performance (London; New York: Routledge, 2000). Mullins, Edwin. The Pilgrimage to Santiago (New York: Interlink Books, 2001). Nolan, Mary Lee. Christian Pilgrimage in Modern Western Europe (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, c1989.) Ohler, Nobert. The Medieval Traveller (Trans. By Caroline Hiller, The Boydell Press: UK, 1989), 97-101 Rudolp, Conrad. Pilgrimage to the End of the World: the Road to Santiago de Compostela (Spain, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 4. Ruiz, Teofilo F. “Merchants, Trade, and Agriculture,” in Crisis and Continuity, Land and Town in Late Medieval Castile (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, c1994). pp.220-223. Sumption, Jonathan. Pilgrimage: An Image of Mediaeval Religion (London: Faber & Faber, 1975), 163. Turner, Victor Witter. Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture: Anthropological Perspectives (New York: Columbia University Press, 1978). Walker, Peter. “Pilgrimage in the Early Church.” In Craig Bartholomew & Fred Hughes eds. Explorations in a Christian Theology of Pilgrimage (Aldershot, Hants, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004), Webb, Diana. Medieval European Pilgrimage (New York: Palgrave, 2002). 22