Drama - (ISEC) 2005

advertisement

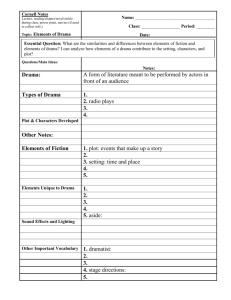

ISEC 2005 INCLUSION: CELEBRATING DIVERSITY? 1st-4th August 2005 University of Strathclyde Glasgow, Scotland DRAMA: AESTHETIC PEDAGOGY FOR SOCIALLY CHALLENGED CHILDREN Dr Melanie Peter Senior Lecturer in Early Childhood and Special Needs Anglia Polytechnic University, Chelmsford, UK m.peter@apu.ac.uk Introduction After twenty years in special education, convinced of the effectiveness of drama as a learning medium for children with wide-ranging needs, my most recent work has brought me to understand why this should be so. Researching drama with some of the most creatively and socially challenged children, has provided a rationale and highlighted effective strategies for the approach I have been developing ever since I first entered the field, in my quest for drama to be taken seriously as pedagogy. Formative working experiences in the early 1980s in long-stay institutions for adults with learning disabilities infused in me a determination to enable them to achieve a sense of creative fulfilment (Maslow 1998), sadly lacking in their spiritual and social isolation at the time. Ever since, I have never been able to understand why it is that those that find creativity and playfulness the most challenging, are deemed to need less of it not more! Current favoured specialist approaches still tend to be highly structured, such as TEACCH (Teaching and Educating Autistic and Communication impaired Children – Schopler and Mesibov 1995) and PECS (Picture Exchange Communication System – Bondy and Frost 1994). But times are a-changing… With recent legislation such as the 2001 Special Educational Needs (SEN) and Disability Act making exclusionary practice potentially a discrimination issue, practitioners now face the ultimate challenge in respect of those most socially challenged children. There is a growth of interest in psychological research highlighting the importance of early interactive play foundations for subsequent development that is influencing pedagogy (Hewett and Nind 1998); neuroscience is also indicating the significance of affective brain functioning in learning (Damasio 2003). Following National Curriculum revisions (DfEE 1999a), drama now finds itself compulsory within the core subject of English - strengthened too by guidance to support children with SEN (DfES 2005, Peter and Grove 2005)! Can drama really be a viable pedagogy even for those with autistic spectrum disorders (ASDs)? Following the ‘All our Futures’ NACCCE Report (DfEE 1999b), whilst creativity is now recognised as making a significant different to children’s educational experience and achievement, can that really be the case for those with ASDs, when one of their diagnostic criteria is lack of flexible thinking? 1 This paper demonstrates how drama (paradoxically) is capable of motivating even hard-to-reach children, and developing their essential creativity at the core of their difficulties. It explores drama as an aesthetic pedagogy (Elliott 2003) - ‘aesthetic’ from the Greek aesthetikos meaning a state of human consciousness and knowing, more than animal sensory awareness (Witkin 1974). Drama-in-education exemplifies this, as an interactive, dynamic learning context, open to a diversity of outcomes with conversation at its core. It hinges on understanding of social narrative, as children gain insight into why people think and behave as they do, and the consequences of social behaviour. Popular psychology has indicated the importance of children’s emotional understanding (Gardner 1983, Goleman 1995); drama may enable even those that are most socially challenged to begin to make sense of their feeling responses - to develop a narrative sense of identity, towards more effective participation within a social world. Drama: an aesthetic learning medium Historically the art form of drama has provided a frame for societies across time to explore issues of human behaviour and social narratives in analogous life situations. Classroom drama can enable children to explore such issues and offers a child-centred approach to curriculum planning. Drama as aesthetic pedagogy involves children in inquiring into problematic situations and abstracting from them principles to guide problem-solving activities (Elliott 2003). Because they are wittingly caught up in the pretence, children may gain an analytic reflective window on their own and others’ play behaviour as they evaluate implications of their affective play responses. The proviso for children with learning difficulties is that explicit opportunities are set up for them to reflect and make connections between their experiences in the drama and the real world (Peter 2003), as to greater or lesser degree, they have difficulty in generalising between contexts. The power and scope of drama lies in a state of ‘metaxis’ (Boal 1979), as children hold in mind more than one world; this in itself demands a flexibility that may strengthen brain architecture involved. This may then support more creative and flexible thinking and consequent alignment with the development of communication and social interaction skills, even in children with profound autism (Sherratt and Peter 2002), so addressing their diagnostic triad of impairments (Wing 1996). Unlike Heathcote’s view (Wagner 1976) that children with learning difficulties should drift imperceptibly into make-believe by chancing upon some archetypal character (a tramp, princess) in need of help, my experience is that they need to be involved in consciously constructing the drama context if they are to benefit from drama’s ‘double edge’. This is crucially important too, to protect them emotionally from failure (Bolton 1984), as any ‘mistakes’ are made by the notional characters they are playing, not themselves directly. This may be achieved by building up the drama painstakingly in small increments, gradually building volume, cross-checking that everyone is ‘with it’, and involving them in physically blocking out the drama space, working from the concrete to the abstract. Importantly too, children need to be involved in de-roling afterwards, returning the set to its original state. Similarly, it has proved helpful to use a simple prop or item of costume to signify when talking to them in role, clarifying when the make-believe is starting and stopping. 2 I have challenged children with a range of learning difficulties to utilise their thinking and resourcefulness in a range of analogous life situations, not just providing help. Working in role in particular, on the inside of the drama, has proved uniquely powerful in shaping the drama covertly from within (O’Neill and Lambert 1982), and to challenge children directly. This circumvents complex language constructions and sustains tension, without breaking the fragile fiction being created and risking possible loss of concentration – children literally ‘losing the plot’. Drama has facilitated exploration of power and inequality issues as the usual perception of teacher as authority figure shifts – particularly poignant in children so often in position of dependency, even if hampered at times by a gap between their ideas and their capability of communicating them (Detheridge 2002). Their idiosyncratic responses symptomatic of wide-ranging disabling conditions have further compounded issues of interpretation of the workings of their mind – and my consequent evaluation of their possible learning. Developing a hierarchy of questioning, moving between closed and open questions has elicited responses from those with limited verbal ability, and using a multi-modal approach, combining speech with signing (gesture and/or graphics) has supported them in accessing meaning. Using other visual hooks (pictures, puppets, masks, attractive props) has not only helped rivet their attention, but also provided a context for early declarative communication, crucial for establishing early foundations of shared meaning: objects for showing, giving, establishing gaze alternation, joint attention and pointing gestures (Park 2002). These have further significance in drama as ‘objects of reference’ (Park 2001) – representations to support communication of meaning, as opposed to their utilitarian function; this may be acquired in process, for example making explicit the symbolising of a cardboard box to be a television set. Incorporating items and themes of personal interest and salience will further support their engagement and hold affective resonance in perceiving shared relevance (Jordan 1999, Sherratt 2002). An ebb and flow of energy levels, breaking up activity with a range of active and static tasks, helps prevent concentration wandering. Children’s spontaneous responses may necessitate responding contingently, investing significance and intention to an idiosyncratic comment or reaction to fit the evolving fictitious context and to create a social meaning; inaccurate responses may be better ignored and followed up later, rather than break the evolving narrative. At other times, the narrative may need to be slowed down to prevent children from rushing headlong, to think through implications, establish consensus and consolidate developments. Information may need to be filled in sensitively, sufficient to ensure all are enabled to contribute, which helps their emotional investment in the activity and a sense of ownership. These strategies have enabled explication with children with wide-ranging learning difficulties of ‘lived through experience’ (Heathcote 1984: 97). Drama has also enabled them to explore cultures or worlds otherwise difficult or impossible for them to access; for example, experiences at the Home Front during the Second World War (Peter 1995). Even children with severe learning difficulties have surprised with the extent to which they have engaged in imagined worlds, and gained insight into the drama form, commenting on its relative effectiveness and negotiating their future 3 learning (Peter 1995), using drama as a metaphorical device for exploring a range of perspectives on a topic – a way of thinking about life (O’Neill 1996). Drama: narrative pedagogy Harnessing drama conventions from mainstream practice has enabled children with learning difficulties to explore issues embedded in texts, to go beyond using drama simply to act out a story line. Zipes (1983), recognised the liberating potential of fairy tales, and challenged Bettleheim’s (1976) Freudian view of them as concerned with psychological processes and socialisation of the child not to be tampered with. Gilligan (1982) considered narrative story telling as the most effective means of transmitting moral knowledge; similarly, Bruner (1990) points out that telling a story necessarily involves taking a moral stance. Young children may make their earliest moral judgements in terms of the powerful opposites found in stories - weak/strong, good/bad, happy/sad (Whitehead 1997). Developing drama from story therefore may enable exploration of cultural traditions and values (Godwin and Perkins 1998, Hendy and Toon 2001), with moral life at its core. Children may re-examine a story’s idea, experiment with the drama form and ‘play’ with the narrative, and then in reflection, come to an understanding of both the story’s possibilities and the art form used to create it (Booth 2000). Grove and Park (2001) illustrate how theatrical devices may be used for children with learning difficulties to explore key moments in Shakespeare’s Macbeth – ‘the territory of social relationships, of moral and emotional development’ (Grove and Park 2001: 18). I have extended them further to explore consequences and implications arising from key moments (Peter 1996, Peter 2003, Sherratt and Peter 2002). Deviating from a storyline as known is crucial for understanding that things can be different, and that they can be instrumental in causing that to be so. In the video age, even those with autism and severe learning difficulties may grasp that a narrative does not have to unfold at life pace, but can be ‘fast forwarded’ or ‘rewound’ to revisit a key moment as the starting point for drama. Also the idea that ‘conflict’ – feelings of unease in grappling with decisions, problems, dilemmas – are part of what constitutes being in the world, and that compromises can be worked at and agreed, and resolutions found as they create a new narrative and work through sorting out an analogous life situation. For example, Michael is five years old and has global learning difficulties compounded by a severe expressive language disorder and associated behavioural learning needs; he is included in a mainstream Reception class, where his favourite activity is to indulge his passion for playing with his model dinosaurs in the sand pit. Michael tended to be ostracised by his peers; some children also felt intimidated by older children with additional needs in the school. Content for the drama was selected to exemplify the issue: a children’s picture storybook Bear Snores On (Karma Wilson, 2001, Simon and Schuster) as a vehicle for exploring their feeling responses to moral dilemmas and possible problems arising. A stream of creatures seek shelter from wintry conditions by tiptoeing into the cave of a hibernating bear; a party gradually develops, Mouse seasons the stew, and a small pepper fleck makes the bear… [achooo!!!]. At this point of high tension, the story is stopped: the children help adapt the classroom to create the set (masking tape pathway leading to the Bear’s lair, 4 cardboard cut-outs taped onto chairs for trees), and the teacher goes into role as the sleeping Bear, donning fake fur wrap in full view of the children. This scary monster immediately holds salience for Michael and his attention is captivated! The moment is revisited when the Bear (teacher-in-role) awakes, and the class (notionally in role as creatures) flee shrieking back to the safety of their story corner! The atmosphere is electric as the Bear follows them snarling, responding to Michael’s interjections and soaking up potential management chaos through the role. The Bear start to sob, upset at their jeering, and having no friends and missing the party… Michael is the first to show compassion (‘Don’t cry, Bear’), and proceeds to take leadership responsibility for the group: they will continue the party at the lair and invite him too! Michael’s status is elevated in the eyes of his peers, and also his selfesteem: he beams delightedly at appreciation of his sustained initiatives and sensitivity. Sitting around the fire (improvised from twigs and red tissue paper) in the lair, and eating real popcorn - a symbol of shared connectedness – teacher-in-role slows the pace and asks if they ever feel left out; discussion is sustained in role as they explore the perspective of the ‘outsider’. Out of role, and the classroom returned to its original state, on resuming reading of the picture story, the children connect with deeper meanings in the text. In response to probing questioning, they comment that the Bear was angry not just because he had been woken up, but because he had missed the party and felt left out. The level of empathy these 4-5 year olds display is in advance of that suggested by Harris et al (1986) in research with 6 year olds: knowledge that the emotion displayed was not always the same as what was felt. The drama seemed to enhance a shift in their social perspective taking, through explicit presentation of the position of the ‘outsider’ via the teacher-in-role strategy: from initial guffawing, they were able to offer the kind of help they would find comforting. Questioning towards the end of the drama elicited a strategy from them for including an isolated individual in the play, with clear appreciation that the person would then feel happy. Several weeks later, a boy mentioned to me that he had seen [John] on his own in the playground, so he went up to him and asked him if he’d like to play hide and seek. This suggests the power of the drama medium for providing a memorable learning experience: the story had informed his capacity to make such generalisations, with the drama enabling him to capture the feel of the moral impulse (Winston 1998). Bolton and Heathcote (1999) identify three significant dynamics in drama that may either bring about a change of perspective directly (as in the lesson above), or through constructing a platform for developing a necessary further stage of constructive reflection beyond role-play. Firstly, an energising shared learning context (Michael was drawn irresistibly with sustained engagement hitherto unseen). Secondly, the children were stimulated by a vested interest derived from a point of view (enjoyment at participating in a party), highlighted by a contraposition (Bear left out of the fun). Thirdly, the self-spectatorship brought about had appeared to be about something else, however, one-step removed Michael’s peers could explore their possible reactions to his behaviour and begin to empathise with his and others’ positions on the margins. Drama: narrative social identity Through collaboration on a real and fictional level, drama moves children closer to enhanced social understanding as they explore a range of social roles, how responses 5 are apt to be construed and consequences of social behaviour (MacIntyre 1981, Winston 1998). Research has shown a correlation between the amount and complexity of role-play in typically developing children, and their developing social competence (Fein 1984, Connolly and Doyle 1984, Howes 1983). Dunn’s (1988, 1991) studies indicate the significance of warm family relationships and highly emotional interaction between siblings, with children as young as 18 months engaged in role-play instructed by their older brothers and sisters. This suggests the value of inclusive make-believe experience with more knowledgeable players for those at early stages of learning, and the significance of highly affective interaction. However, this rather assumes an innate predisposition towards relatedness. What of those children seemingly profoundly challenged in this regard, exemplified by those on the autistic spectrum? Mundy et al (1993) comment on the marked lack of emotional expression in children with autism and their apparent lack of engagement in pretend play activities. This view contrasts with my own experiences over the years, where even children with profound autism seemed responsive in my drama sessions. Why should drama be so potent? Frith (1989) explains autism as the inability to draw together information so as to derive coherent and meaningful ideas; there is a fault in the predisposition of the mind to make sense of the world. Grandin (1995), an adult with autism, describes how she uses her intellect to learn social skills, with logic guiding her decisions rather than her emotions. However, whilst it may be possible to ‘train’ people with autism to recognise and respond to certain social cues, social understanding has to occur at a deeper level. Life as it is experienced between individuals is bound up in complex social relationships and characterised by affective elements (Gilligan 1982, Hobson 2002). Recent neuropsychological research into brain functioning has highlighted the significance of these affective aspects for effective learning (Iveson 1996, Damasio 2003). It is plausible that drama stimulates neurochemical reactions that facilitate rational and irrational connections, so that more flexible patterns of thought emerge. It may energise those areas of the brain responsible for affective activity thought to be under functioning in autism (Damasio and Maurer 1978; Ramachandran 2003). This may provide a coherent rather than fragmented learning experience (Sherratt and Peter 2002), reaching to the very core of their difficulties by addressing their primary disconnectedness. As Neelands (1992) further posits, a sense of coherence is also afforded through the effect of using drama to recreate ‘real life’ demands and situations for the learner, which provides relevance to the curriculum. A crucial catalyst would seem to be the strong affective input infused by the teacher working in role – melodrama and blatant signalling of meaning, use of humour, excitement, suspense and injecting emotional warmth. Working inside the makebelieve facilitates a ‘meeting of minds’, a sense of relatedness and embryonic theory of mind (Trevarthen 1979, Oates 1994), similar to that experienced by a young infant with its caregiver. Nind (2000) acknowledges the natural flow of interaction may be difficult to sustain with some children, due to their irascibility, preoccupation, hypersensitivity to sensory stimuli, lack of feedback, or absence of mutual gaze. All the more reason for persisting! Mirroring and reinforcing emotional responses, and mutual imitation are key factors for sharing emotional meanings and for building a concept of self and other (Rogers and Pennington 1991, Meltzoff 1990, Hobson 2002). This requires senstitive attunement (Stern 1985) to express a shared feeling, 6 which for some children may necessitate a more oblique, less invasive approach (Williams 1996). From shared foundations and being drawn into the feelings and actions of others, this may led to mental perspective taking and creative symbolising (Hobson 2002) – social imagination will require a developing ability to incorporate a representation of others’ mental states without necessarily sharing them (Harris 1989). Hobson (2002) disputes whether children with autism are affected on a feeling level, commenting on the difference in the pull towards sharing experiences. However, their latent sociality has been apparent in my drama sessions, displaying uncharacteristic sustained affective engagement (Volkmar 1987). Enhanced emotional encounters engineered especially by teacher-in-role may have been the trigger for their more intuitive responses, also prompting an explicit sense of agency. This may accommodate views of autism as resulting from disturbance to primary instincts towards relatedness in infancy (Trevarthen 1979). It also challenges cognitive explanations of difficulties in autism associated with theory of mind (Baron-Cohen 1993) founded on their alleged inability to engage in pretence due to a possible fault in hard-wiring; this is claimed to undermine an innate predisposition to perceive and form representations of the intentions of others (Ozonoff et al 1991, Leslie 1987). Drama may address other cognitive explanations of autism that have highlighted difficulties with executive functioning, and failure of systems that guide behaviour using representations of affective and social information (Damasio and Maurer 1978). It may be that objects of reference used in the drama support engagement in pretence without having to generate the retrieval of a mental representation (Jarrold et al 1996). It is plausible that items of costume to indicate teacher-in-role may have similar affective resonance, and trigger recall of representations of affective and social information. Having been explicitly involved in creating the drama context, even non-verbal children with autism in my sessions do not appear to have difficulty in disengaging from the immediate environment and entering the make-believe and using representations (Russell and Jarrold 1995). It may be that drama can expedite the development of pretend play in children with autism: through an apprenticeship approach, they may be taught explicitly how to make their play more complex and how representation works, and so benefit from natural learning processes seen in typical development. In role-play children explore different perspectives with others and learn to manage themselves in situations (Vygotsky 1978, Bruner 1986, Harris 2000). Play activities based on real-life scenarios enable them to learn about cultural conventions and make them their own: children tend to stretch themselves and push boundaries as they explore and experiment with their social understanding, which in itself is a big developmental leap (Vygotsky 1978). They become ‘world weavers’ (Cohen and MacKeith 1991), suspending reality and creating novel forms of thinking and meaning, integrating cognitive logic and affective engagement in developing social cognition (Wood and Attfield 1996). Drama: a narrative intervention for autism However, social understanding is more than just a function of cognitive and affective processes: it has a distinct narrative dimension to it as well. As Kierkegaarde (cited in Lawler 2002) said, ‘life is lived forward but understood backwards’: the 7 significance of earlier events in conferred by what comes later, and provides a narrative sense of identity (Ricoeur 1991). Children create a sense of ‘self’ as they put their thoughts and experiences into a narrative and relate this to others, sharing in personal stories and also those contained in cultural texts; understanding of narrative form will be a crucial turning point (Jones 1996). Harris and Levers (2000) suggest that play in children with autism is necessarily restricted because of impairment in the generation or execution of internal plans or narratives. Whether this is a cause or a consequence of their difficulty with understanding other people’s intentions and possible consequences is a moot point. Bruner and Feldman (1993) actually propose autism as a failure in narrative ability – to recognise patterns and sequences in life: even though they can be taught predictable routines, they find anticipation and changes problematic; they also tend not to offer comment on their experiences nor involve themselves in chat for the sake of it (TagerFlusberg 1993). They claim this stems from early difficulty in ‘cultural framing’ gained through early interactive play formats with caregivers, such a peep-bo games. Jordan (2001) muses whether it is difficulty with seeing the narrative form that undermines early interaction, or whether difficulty in interaction makes it problematic to acquire appreciation of narrative form. Whichever, she acknowledges how this would interfere not only with early forms of play, but all subsequent make-believe (and therefore learning) in which joint narratives were developed, such that many of the characteristics of children with autism could stem from this difficulty. Over the years, I have developed a drama game strategy originally formulated by John Taylor (1986) for working with children with learning disabilities that was a prototype for my own pivotal framework subsequently termed a Prescribed Drama Structure (PDS – Peter 1994). This enables players to consolidate a ritualised play format as a template for subsequent understanding of social narrative and shared meaning, and to integrate cognitive and affective aspects involved in early development. It would seem that the predictable shape of the PDS offers the chance to consolidate the foundations of social patterning and the ability to use narrative form, ‘a way of giving meaning and significance to the endless stream of sensations and events’ (Whitehead 1997: 90). At early stages of learning, this enables children to revisit pretence as experienced in early interaction, founded in the psychological rationale of adults and older peers play tutoring as seen in typical development (Vygotsky 1978, Wood et al 1976, Dunn 1988, 1991). Once playing fluently, the PDS can then be opened up through an unexpected outcome rather than that predicted, as a way of easing children into more open-ended drama (Peter 2001). For example, a PDS was devised around the forgotten character of teacher-in-role as Mrs Pig (mother of the Three Little Pigs), fed up with housework; she is delighted as each child in turn helps with a chore by selecting an item from a number of photographs before finding the corresponding prop and improvising the activity. The pivotal key moment is Mrs Pig’s anticipated reaction when she realises she still has chores remaining; this is framed by a chant with strong rhythmic appeal (Park 2004). This activity was carried out with three profoundly socially challenged boys with autism and severe learning difficulties over several sessions (Peter and Sherratt 2003), at the end of which Joe showed ‘combinational’ creativity (Boden 2001) - he made new associations with familiar ideas, as he played functionally with a feather duster, utilising it appropriately on a table top and then the windows. 8 Norman showed ‘exploratory’ creativity (Boden 2001), spontaneously extending the boundaries of a familiar play narrative (drying up using a tea towel) by then picking up a cup and pretending to drink. Remarkably, he delighted in calling others’ attention, indicating his desire to share the format. Significantly too, Norman demonstrated ‘transformational creativity’ (Boden 2001), spontaneously assuming the teacher-in-role’s items of costume and using props in short socio-dramatic scripts (Smilansky 1968), suggestive that he was intrigued to explore a new perspective. From having been prompted to participate in role-play in previous weeks, the security of the predictable narrative of the PDS paradoxically liberated Norman into embryonic role taking (Fein 1984, Harris 2000). This took him beyond organising himself in the role of another, to a level where he was beginning to organise himself in the light of the attitudes and perspective of the role responses of another. Carl was most intrigued at moments when the familiar narrative was ‘tweaked’, for example, by a different member of staff playing teacher-in-role as Mrs Pig. This uncharacteristic receptiveness to embrace change suggests that exposure to makebelieve may have unlocked mechanisms otherwise unavailable. Increased fluency in play responses was also observed in a similar group of children – generalised too significantly, to purposeful play with props between sessions. Boden (2001) notes that familiar story structures afford conceptual spaces to be explored, so that gradually the child learns what lies within them and what does not. This may be expedited through drama when the generative conditions are right: an underlying framework that integrates children ‘s cognitive interest and affective engagement within an appropriately challenging play narrative. In devising a theoretical model for generative conditions for meaningful learning contexts in drama (see Figure 1), paradoxically I was struck by the inclusive relevance of Mönks (1992, in Eyre 1997) multi-factional model of giftedness if references to exceptional ability were removed. This indicates that whilst certain children (firstly) may have latent ability, this will only flourish if (secondly) they are suitably motivated, and (thirdly) if they have opportunity within an activity to ‘make it their own’. Mapping this multi-factional model onto a triad of competencies achieved by inverting the autistic triad of impairments in communication, social interaction and inflexible thinking (Wing 1996), highlights pedagogical implications for facilitating improvements in children’s communication, sensitivity and creativity. All three dimensions (cognitive, affective and narrative) need to be addressed as prerequisites to ensure an experience is meaningful and coherent, towards a more integrated and intuitive social understanding. 9 INTEREST AFFECT Object of reference: prop, scenery, costume – familiar or novel? Personally appealing or salient item Sensitive attunement by adult – high or low level? Developmentally appropriate level of challenge COMMUNICATION SENSITIVITY Emotional response Perceptual recognition Engagement ‘That’s my teacher wearing an apron’ ‘I like that – it has lots of blue on it and that’s my favourite colour’ ‘I want to play with her again’ Perceptual memory ‘I need something to use for a cooker’ Coherence a Affective memory ‘I played with her in that apron before & it felt good’ Play sequence (narrative framework) ‘I can pretend to cook the dinner and she can pretend to taste it’ CREATIVITY STRUCTURE Complexity of the drama - Element of change? Choices and decisions? Social grouping - play partner(s)? - adult or child(ren)? Fig 1: Drama as aesthetic pedagogy: generative conditions for meaningful learning (developed from Sherratt and Peter 2002, Peter and Sherratt 2003) 10 Conclusion Drama-in-education may facilitate flexible ‘possibility thinking’ (Craft 2001) crucially important if socially challenged children are to embrace change, especially in these fast-moving times. Drama may also support children in learning to be ‘mindful’ (Safran 2001) – not only an open attitude to life, but also an implicit awareness of more than one perspective in situations. Drama exemplifies aesthetic pedagogy: a humanistic narrative learning medium that offers children a unique reflective window onto their own and others’ play responses, to enable them to understand the consequences of social behaviour. This may afford even the most socially challenged children the opportunity to develop an understanding of their place in the world and how to participate within an increasingly inclusive society. Implications arising from early interaction difficulties exemplified by those on the autistic spectrum may account for their subsequent failure in socialisation. Early experiences of pretence would seem severely compromised, which cognitive, affective and some narrative explanations of the condition claim to be a significant factor. An apprenticeship narrative approach through drama enables even profoundly socially challenged children to recapture early experiences of pretence, as the foundation for social understanding and creative fulfilment. Without this, it is hard to see how life for some children will remain anything but fragmented and meaningless, and pedagogy as potentially mind-numbingly anaesthetic. REFERENCES Baron-Cohen, S (ed.) (1993) Understanding Other Minds: perspectives from autism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Bettleheim, B (1976) The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales. London: Penguin. Boal, A (1979) Theatre of the Oppressed. London: Pluto Press. Boden, M (2001) ‘Creativity and Knowledge’, in Craft, A; Jeffrey, B & Leibling, M (eds) Creativity in Education. London: Continuum. Bolton, G (1984) Drama as Education. London: Longman. Bolton, G & Heathcote, D (1999) So you want to use role-play? A new approach in how to plan. Stoke on Trent: Trentham Books. Bondy, A & Frost, L (1994) ‘The Delaware Autistic Program’, in Harris, S L & Handleman, J S (eds) Preschool education programs for children with autism. Austin: Pro-ed. Booth, D (2000) ‘Reading the Stories we Construct Together’, in Ackroyd, J (ed.) Literacy Alive! London: Hodder & Stoughton. Bruner, J (1986) Actual Minds, Possible Worlds. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. Bruner, J (1990) Acts of Meaning. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. Bruner, J & Feldman, C (1993) ‘Theories of mind and the problem of autism’, in Baron-Cohen, S (ed) Understanding Other Minds: perspectives from autism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Cohen, D & MacKeith, S A (1991) The Development of Imagination: The Private Worlds of Childhood. London: Routledge. 11 Connolly, J A & Doyle, A-B (1984) ‘Relation of social fantasy play to social comptetence in pre-schoolers’, Developmental Psychology, 20, 797-806. Craft, A (2001) ‘Little c Creativity’, in Craft, A; Jeffrey, B & Leibling, M (eds) Creativity in Education. London: Continuum. Damasio, A R (2003) Looking For Spinoza: Joy, Sorrow and the Feeling Brain. New York: Harcourt. Damasio, A R & Maurer, R G (1978) ‘A neurological model for autism’, Archives of Neurology, 35, 777-86. DfEE (1999a) The National Curriculum: handbook for primary teachers in England. London: The Stationery Office. DfEE (1999b) All Our Futures: Creativity, culture and education. Report by the National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education to the Secretary of Strate for Education and Employment, and the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport. Sudbury: DfEE. DfES (2005) Speaking, Listening , Learning: working with children who have special educational needs. Norwich: HMSO. Detheridge, T (2000) ‘Research involving children with severe learning difficulties’, in Lewis, A & Lindsay, G (eds) Researching Children’s Perspectives. Buckingham: Open University Press. Dunn, J (1988) The Beginnings of Social Understanding. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Dunn, J (1991) ‘Young children’s understanding of other people: evidence from observations within the family’ in Frye, D & Moore, C (eds) Children’s Theories of Mind. Hillsdale (N J): Lawrence Erlbaum. Elliott, J (2003) ‘Re-Thinking Pedagogy as the Aesthetic Ordering of Learning Experiences’. University of East Anglia, Norwich. Unpublished paper. Eyre, D (1997) Able Children in Ordinary Schools. London: David Fulton Publishers. Fein, G G (1984) ‘The self-building potential of pretend play or “I got a fish, all by myself”’, in Yawkey, T D & Pellegrini, A D (eds) Child’s Play: developmental and applied. Hillsdale (N J): Lawrence Erlbaum. Frith, U (1989) Autism: Explaining the Enigma. Oxford: Blackwells. Gardner, H (1983) Frames of Mind. London: Fontana Press. Gilligan, C (1982) In a Different Voice. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. Godwin, D & Perkins, M (1998/2002) Teaching Language and Literacy in the Early Years. London: David Fulton. 2nd edition, 2002. Goleman, D (1995) Emotional Intelligence. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. Grandin, T (1995) ‘How people with autism think’, in Schopler, E & Mesibov, G B (eds) Learning and Cognition in Autism. New York: Plenum Press. Grove, N & Park, K (2001) Social Cognition through Drama and Literature for People with Learning Disabilities. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. Harris, P L (1989) Children and Emotion. Oxford: Blackwells. Harris, P (2000) The Work of the Imagination. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. Harris, P L & Levers, H J (2000) ‘Pretending, imagery and self-awareness in autism’, in Understanding Other Minds, volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Harris, P L; Donnelly, K, Guz, G R & Pitt-Watson, R (1986) ‘Children’s understanding of distinction between real and apparent emotion’, Child Development, 57, 895-909. Heathcote, D (1984) – ref O’Neill, C & Johnson, L (eds) – op cit Hendy, L & Toon, L (2001) Supporting Drama and Imaginative Play in the Early Years. Buckingham: Open University Press. 12 Hewett, D & Nind, M (eds) (1998) Interaction in Action. London: David Fulton Publishers. Hobson, P L (2002) The Cradle of Thought. London: Macmillan. Howes, C (1983) ‘Peer interaction of young children’, Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, no 217, 53(1), Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Iveson, S D (1996) ‘Communication in the mind’, Paper to the International Congress of Psychology XXVI Montreal. International Journal of Psychology, 31, 254. Jarrold, C et al (1996) ‘Generative deficits in pretend play in autism’, British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 14, 275-300. Jones, R (1996) Emerging Patterns of Literacy: a multi-disciplinary perspective. London: Routledge. Jordan, R (1999) Autistic Spectrum Disorders. London: David Fulton Publishers. Jordan, R (2001) Autism with Severe Learning Difficulties. London: Souvenir Press. Lawler, S (2002) ‘Narrative in Social Research’, in May, T (ed.) Qualitiative Research in Action. London: Sage. Leslie, A M (1987) ‘Pretence and Representation: the origins of theory of mind’, Psychological Review, 94, 412-26. MacIntyre, A (1981) After Virtue. London: Duckworth. Maslow, A (1998) Towards a Psychology of Being. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. Meltzoff, A N (1990) ‘Towards a developmental cognitive science: the implications of cross-modal matching and imitation for the development of representation and memory in infancy’, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 608, 1-37. Mönks, F J (1992) ‘Development of gifted children: the issue of identification and programming’, in Mönks, F J & Peters, W (eds) Talent for the Future. Assen/Maastricht: Van Gorcum. Mundy, P et al (1993) ‘The theory of mind and joint attention deficits in autism’, in Baron-Cohen, S et al (eds) Understanding Other Minds: perspectives from autism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Neelands, J (1992) Learning through Imagined Experience. London: Hodder & Stoughton. Nind, M (2000) ‘Intensive Interaction and Autism’, in Powell, S (ed.) Helping Children with Autism to Learn. London: David Fulton Publishers. Oates, J (1994) ‘First Relationships’, in Oates, J (ed) The Foundations of Child Development. Oxford: Blackwell/The Open University. O’Neill, C (1996) ‘Into the Labyrinth: Theory and Research in Drama’, in Taylor, P (ed) Researching Drama and Arts Education. London: Falmer Press. O’Neill, C & Lambert, A (1982) Drama Structures. London: Hutchinson. O’Neill, C & Johnson, L (eds) (1984) Dorothy Heathcote: Collected Writings on Drama and Education. London: London Drama with Heinemann. Ozonoff, S et al (1991) ‘Executive function deficits in high-functioning autistic children: relationship to theory of mind’, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 32, 1081-106. Park, K (2001) ‘Oliver Twist: an exploration of interactive storytelling and object use in communication’, British Journal of Special Education, 28 (1), 18-23. Park, K (2002) ‘Macbeth: a poetry workshop on stage at Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre’, British Journal of Special Education, 29 (1), 14-19. Park, K (2004) ‘Interactive storytelling: from the Book of Genesis’, British Journal of Special Education, 31 (1), 16-23. Peter, M (1994) Drama for All. London: David Fulton Publishers. Peter, M (1995) Making Drama Special. London: David Fulton Publishers. 13 Peter, M (1996) ‘Developing Drama from Story’, in Kempe, A (ed.) Drama Education and Special Needs. Cheltenham: Stanley Thornes. Peter, M (2001) ‘All About…DRAMA’ (8-page pull-out feature), Nursery World, 6 December. Peter, M (2003) ‘Drama, Narrative and Early Learning’, British Journal of Special Education, 30 (1), 21-27. Peter, M & Grove, N (2005) ‘Getting in on the Act’, TES Extra for Special Needs, May 2005, p 3. Peter, M & Sherratt, D (2003) ‘Play-Drama Intervention: A narrative approach to developing social understanding in Children with Autistic Spectrum Disorders’, in conference handbook: Autism: alternative strategies. New Delhi: Tamana Association. (Sept 3-5), 52-67. Ramachandran, V (2003) ‘The Emerging Mind: Lecture 5 – Neuroscience, the New Philosophy’, Reith Lecture 2003, BBC Radio 4, 30th April. Ricoeur, P (1991) – ref Wood, D. (ed.) – op cit Rogers, S J & Pennington, B F (1991) ‘A theoretical approach to the deficits in infantile autism’, Development and Psychopathology, 3, 137-62. Russell, J & Jarrold, C (1995) ‘Executive deficits in autism’, paper to the Society for Research in Child Development: Indianapolis 1995. Safran, L (2001) ‘Creativity as “Mindful” Learning: A Case from Learner-Led HomeBased Education’ in Craft, A; Jeffrey, B & Leibling, M (eds) Creativity in Education. London: Continuum. Schopler, E & Mesibov, G (1995) ‘Structured teaching in the TEACCH approach’, in Schopler, E & Mesibov, G (eds) Learning and Cognition in Autism. New York: Plenum Press. Sherratt, D (2002) ‘Developing pretend play in children with autism: an intervention study’, Autism: the International Journal of Research and Practice, 6 (2), 169-181. Sherratt, D & Peter, M (2002) Developing Play and Drama in Children with Autistic Spectrum Disorders. London: David Fulton Publishers. Smilansky, S (1968) The Effects of Sociodramatic Play on Disadvantaged Pre-school Children. Newy York: Wiley. Stern, D (1985) The Interpersonal World of the Infant. New York: Basic Books. Tager-Flusberg, H (1993) ‘What language reveals about the understanding of mind in children with autism’, in Baron-Cohen, S (ed) Understanding Other Minds: perspectives from autism. Oxford: Blackwells. Taylor, J (1986) ‘Frankenstein’s Monster’, London Drama Magazine, 7 (3), Autumn, 17-19. Trevarthen, C (1979) ‘Communication and co-operation in early infancy: a description of primary intersubjectivity’, in Bullowa, M (ed) Before Speech. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Volkmar, F R (1987) ‘Social Development’, in Cohen, D J and Donnellan, A (eds) Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders. New York: Wiley. Vygotsky, L (1978) Mind in Society: the development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. Wagner, B J (1976) Dorothy Heathcote: Drama as a Learning Medium. London: Hutchinson. Whitehead, M (1997) Language and Literacy in the Early Years. London: Paul Chapman Publishing. Williams, D (1996) Autism: an Inside-Out Approach. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. 14 Wing, L (1996) The Autistic Spectrum: a guide for parents and professionals. London: Constable. Winston, J (1998) Drama, Narrative and Moral Education. London: The Falmer Press. Witkin, R (1974) The Intelligence of Feeling. London: Heinemann. Wood, D (ed.) (1991) On Paul Ricoeur: Narrative and Interpretation. London: Routledge. Wood, D J; Bruner, J S & Ross, G (1976) ‘The role of tutoring in problem-solving’, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17, 89-100. Wood, E & Attfield, J (1996) Play, Learning and the Early Childhood Curriculum. London: Paul Chapman Publishing. Zipes, J (1983) Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion. London: Heinemann. 15