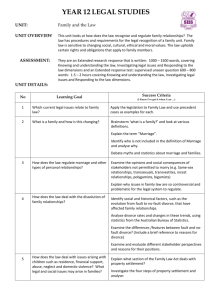

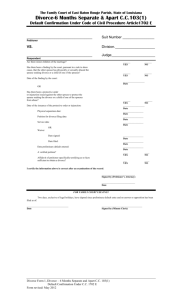

petitions for divorce - The Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong

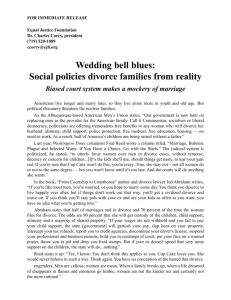

advertisement