University of Southampton

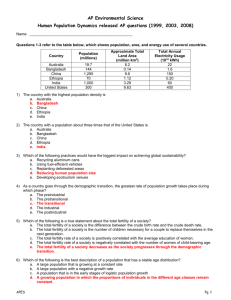

advertisement