Educational Toolkit on Beverage Alcohol Consumption

advertisement

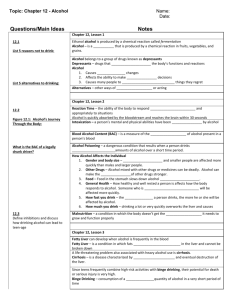

III. Starting the Dialogue This Tool Kit was developed to assist health care professionals in communicating the Dietary Guidelines for Americans’ (2005 (1)) guideline on beverage alcohol consumption with their patients and clients. This section focuses on assessing the individual’s knowledge of beverage alcohol and will assist the health care professional in determining which, if any, of the materials in this Tool Kit are appropriate for a discussion, or if the individual may need a referral for alcohol abuse or alcohol dependence treatment. A. Why talk about beverage alcohol consumption? Research findings suggest that adult patients who frankly discuss alcohol consumption with their health care professionals are able to make the most informed decisions about how to either include beverage alcohol as part of a healthy diet or abstain. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism has emphasized the critical role that health care professionals play in communicating about responsible beverage alcohol consumption or abstention. For example, “Your patients look to you for advice about the risks and benefits associated with drinking. Research, in fact, demonstrates that simply discussing your concerns about alcohol use can be effective in changing many patients’ drinking behavior before problems can become chronic” (2). Furthermore, a review of the literature on brief interventions concluded that patients reporting drinking alcohol at risky levels who received a brief counseling session from their physicians were likely to moderate their drinking or abstain (3, 4). A discussion with their patients on drinking will help health care professionals recognize potential problems early and help determine whether a patient is consuming moderately and responsibly, at risk for experiencing adverse consequences, but at a point when brief office counseling can be effective; or identify serious dependency problems that require more intensive treatment and intervention. More than 100 million American adults drink beverage alcohol responsibly. For these adults, moderate consumption of beverage alcohol – distilled spirits, beer or wine – can be an acceptable diet and lifestyle choice. Of course, some individuals should not drink alcohol beverages at all. Adults, who choose to drink, should drink in moderation and responsibly. According to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (2005 (1)) “Moderation is defined as the consumption of up to one drink per day for women and up to two drinks per day for men…. This definition of moderation is not intended as an average over several days but rather as the amount consumed on any single day.” Regardless of the type of drink (distilled spirits, beer, wine), beverage alcohol consumption is associated with health effects – both potentially positive and negative. A critical aspect of responsible drinking is understanding the facts of beverage alcohol equivalence. The alcohol in each type of beverage alcohol product is the same and has the same health effects. Each type of beverage alcohol product can be enjoyed responsibly and each can be abused. According to a 2004 survey of health professionals, 95 percent of the respondents surveyed reported that it is important for people to understand the standard drink definition taught by the federal and state governments to guide responsible decisions about drinking. They also believe that their patients do not know: What is a standard drink A standard drink of spirits, wine and beer each contains the same amount of alcohol The ethanol in all types of beverage alcohol has the same physiological effect on the body (5). The importance of providing information about standard drinks is evident by survey data. For example, a 2001 Gallup poll (6) showed that only 41% of adult Americans polled understood that a standard drink of beverage alcohol – 12 ounces of beer, 5 ounces of wine or 1.5 ounces of 80 proof distilled spirits – each contains the same amount of alcohol. In each edition of Dietary Guidelines for Americans, a standard drink has been central to the discussion on beverage alcohol consumption. What are beverage alcohol products? Fermentable plants are the primary raw materials for beer, wine and distilled spirits. Distilled spirits use the widest variety of plant materials. These can include cereal grains (e.g. corn, rye, barley malt etc.), sugarcane, sugarcane syrup, molasses, fruits, fruit juice and vegetables. Beer begins with grains such as barley and wheat. Hops are added for flavor. Grapes are usually used for wine, but apples, berries, or just about any fruit also can be used for wine production (7). All beverage alcohol products (distilled spirits, beer and wine) are fermented by yeast. Fermentation is a process whereby carbohydrates such as starch and sugars in the plants are transformed into ethyl alcohol and carbon dioxide. The ethyl alcohol molecule produced by the fermentation process is the same for all beverage alcohol products (7). Regardless of how they are produced, a standard drink of distilled spirits, beer and wine all contain the same amount of alcohol (approximately 0.6 fl oz. or 14 grams) (8). According to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (2005(1)) published by the U.S. Departments of Health and Human Services and Agriculture, a standard drink of beverage alcohol is defined as 12 fl oz. of regular beer, 5 fl oz. of wine and 1.5 fl oz. of 80-proof distilled spirits (for a copy of the Dietary Guidelines (2005), see tear pad in Section I and tools for professional education in Section IV). According to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (2005 (1)), a standard drink of regular beer, white/red wine and 80 proof distilled spirits provides 144, 100/105 and 96 calories, respectively. The effects of beverage alcohol on the body from distilled spirits, beer and wine result from the absorption, distribution and elimination of ethyl alcohol, particularly as it relates to blood alcohol concentration. The scientific literature concludes that regardless of the type of drink consumed – distilled spirits, beer or wine – the effect on blood alcohol concentration and related physiological effects are the same (9, 10). 2 B. Early screening and brief intervention 1. Recent Reimbursement Codes As of 2008 for commercial insurance and 2007 for Medicaid and Medicare, reimbursement for screening and brief intervention is available through commercial insurance Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes, Medicare G codes, and Medicaid Health Care Procedure Code Set (HCPCS) codes. A full listing of these codes can be found at www.sbirt.samhsa.gov/coding.htm. Moreover, providers may be reimbursed for screening and brief intervention without specific codes. For more detailed information regarding reimbursement issues, refer to the article Detailed Information About Coding for SBI Reimbursement at the end of this section or at www.ensuringsolutions.org. Coding for SBI Reimbursement Reimbursement for screening and brief intervention is available through commercial insurance CPT codes, Medicare G codes, and Medicaid HCPCS codes. Code Description Fee Schedule CPT 99408 Alcohol and/or substance abuse structured screening and brief intervention services; 15 to 30 minutes $33.41 CPT 99409 Alcohol and/or substance abuse structured screening and brief intervention services; greater than 30 minutes $65.51 G0396 Alcohol and/or substance abuse structured screening and brief intervention services; 15 to 30 minutes $29.42 G0397 Alcohol and/or substance abuse structured screening and brief intervention services; greater than 30 minutes $57.69 H0049 Alcohol and/or drug screening $24.00 H0050 Alcohol and/or drug service, brief intervention, per 15 minutes $48.00 Commercial Insurance Medicare Medicaid Adapted from SAMHSA’s Screening, brief intervention and treatment referral Web site: www.sbirt.samhsa.gov/coding.htm (January 2009). 3 2. Overview Detecting alcohol abuse and dependence early enables clinicians to get their patients the help they need, either by initiating a brief intervention or by referring the patient to treatment. Although screening and brief intervention can benefit all patients, it is most helpful for those who do not have an alcohol disorder, but who are drinking in ways that may be harmful (11). According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (8): Patients are likely to be more receptive, open, and ready to change than you expect. Most patients don’t object to being screened for alcohol use by clinicians and are open to hearing advice afterward. In addition, most primary care patients who screen positive for heavy drinking or alcohol use disorders show some motivational readiness to change, with those who have the most severe symptoms being the most ready. You are in a prime position to make a difference. Clinical trials have demonstrated that brief interventions can promote significant, lasting reductions in drinking levels in at-risk drinkers who are not alcohol dependent. Some drinkers who are dependent will accept referral to alcohol treatment programs. Even for patients who do not accept a referral, repeated alcohol-focused visits with a health provider can lead to significant improvement. At risk drinking is defined by NIAAA as more than 4 standard drinks in a day (or more than 14 per week) for men and more than 3 standard drinks in a day (or more than 7 per week) for women. According to epidemiologic research, at-risk-drinkers may be at increased risk for physical, mental and social problems, but at risk does not necessarily constitute alcohol abuse (8). Alcohol abuse among adults can be identified by screening in a variety of settings such as primary care, emergency room, prenatal care, nutrition consultations, etc. If appropriate screening tools are used, studies have shown that screening is sensitive and that patients are willing to give honest information about their alcohol consumption to health care professionals. There are several effective screening tools, described below, available to assess risk for alcoholrelated problems (8, 11). a. Screening and assessment A Pocket Guide for Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism can help in starting a dialogue on alcohol consumption with your patients and assess their pattern of beverage alcohol consumption. It also provides structured guidance on brief intervention. (A tear pad containing A Pocket Guide for each patient is provided in Section II – The Essentials: Tools and Handouts for Patient Education). 4 Additional and more detailed screening tools for adults, including quantity-frequency interview questions and questionnaires such as the CAGE and AUDIT can also be effective in assessing risk for alcohol-related problems. The CAGE and AUDIT questionnaires are discussed below (8, 11). CAGE questionnaire: In a health care setting, the four-item CAGE questionnaire can be used for early detection of alcohol problems. The first question, “Have you ever felt you should cut down on your drinking?” is an easy, non-threatening question to ask. A positive answer to the first two questions suggests a need for further evaluation and brief intervention. One “yes” response on the CAGE suggests an alcohol use problem and more than one “yes” is a strong indication that a problem exists (11, 12). The four questions are: Have you ever felt you should cut down on your drinking? Have people annoyed you by criticizing your drinking? Have you ever felt guilty about drinking? Eye opener: Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning (an eye-opener) to steady your nerves or get rid of a hangover? KEY: One “yes” response suggests an alcohol use problem. More than one “yes” is a strong indication that a problem exists. If someone is CAGE positive, or even if they are negative, but the clinician still has questions, the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) can be easily administered and is another useful test for early detection of alcohol problems (11, 12). AUDIT questionnaire: The AUDIT is a sensitive screening tool and can identify individuals who have problems with alcohol but who may not be dependent. The 10-item questionnaire can be used to obtain more qualitative information about a patient’s alcohol consumption. It includes questions about quantity and frequency of use, binge drinking, dependence symptoms, and alcohol-related problems (10, 11, 12). The AUDIT questionnaire takes more time than the CAGE or A Pocket Guide to administer. Scoring the AUDIT: Record the score for each response in the blank box at the end of each line, then total these numbers. The maximum possible total is 40. Total scores of 8 or more for men up to age 60 or 4 or more for women, adolescents, and men over 60 are considered positive screens. For patients with totals near the cut-points, clinicians may wish to examine individual responses to questions and clarify them during the clinical examination (8). 5 Place an X in one box that best describes your answer to each question: QUESTIONS 0 1 2 3 4 1. How often do you have a drink containing alcohol? Never Monthly or less 2 to 4 times a month 2 to 3 times a week 4 or more times a week 2. How many drinks containing alcohol do you have on a typical day when you are drinking? 1 or 2 3 or 4 5 or 6 7 to 9 10 or more 3. How often do you have five or more drinks on one occasion? Never Less than monthly Monthly Weekly Daily or almost daily 4. How often during the last year have you found that you were not able to stop drinking once you had started? Never Less than monthly Monthly Weekly Daily or almost daily 5. How often during the last year have you failed to do what was normally expected of you because of drinking? Never Less than monthly Monthly Weekly Daily or almost daily 6. How often during the last year have you needed a first drink in the morning to get yourself going after a heavy drinking session? Never Less than monthly Monthly Weekly Daily or almost daily Never 7. How often during the last year have you had a feeling of guilt or remorse after drinking? Less than monthly Monthly Weekly Daily or almost daily Never Less than monthly Monthly Weekly Daily or almost daily 8. How often during the last year have you been unable to remember what happened the night before because of your drinking? 9. Have you or someone else been injured No because of your drinking? Yes, but not in the last year Yes, during the last year 10. Has a relative, friend, doctor, or other No health care worker been concerned about your drinking or suggested you cut down? Yes, but not in the last year Yes, during the last year Total 6 b. Brief interventions Unlike traditional treatment, which focuses on helping individuals who are alcohol dependent, brief interventions – or short, one-on-one counseling sessions are best suited for individuals who meet the criteria for at-risk drinking or in whom the health care provider feels an alcohol-related problem is developing. The aim is to intervene early and target individuals whose drinking patterns are harmful but who do not necessarily meet diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence. Brief interventions, however, can also help motivate alcohol dependent patients to enter treatment. Brief interventions often emphasize reducing a person’s alcohol consumption to nonhazardous levels and patterns, although abstinence may be encouraged when appropriate (4, 13). Brief interventions typically consist of one to four short counseling sessions and may include approaches such as motivational interviewing. Motivational interviewing is designed to persuade people who are resistant to moderating their alcohol intake or who do not believe their drinking to be harmful or hazardous. It is a patient centered technique that encourages people to decide for themselves by using empathy and warmth rather than confrontation. In addition, health care professionals can assist patients in establishing specific goals and building skills to modify their drinking behavior (4, 13). Studies have shown that, among heavy drinkers, using brief interventions may reduce alcohol consumption by 13 to 34 percent. In these same populations, studies estimate a 23 to 26 percent reduction in mortality following brief interventions. In addition, brief intervention trials have also reported significant decreases in blood pressure readings, levels of gamma-glutamyl transferase, psychosocial problems, hospital days and hospital readmissions for alcohol-related trauma. The follow-up periods for many studies typically range from 6 to 24 months, although some studies have reported sustained reductions in alcohol use over 48 months. Moreover, in alcohol dependent individuals with alcoholrelated medical illness, repeated brief interventions at approximately monthly intervals for 1 to 2 years can lead to significant decreases in consumption, or abstinence (4, 8). Brief interventions can be administered in a variety of settings such as primary care, emergency departments, trauma centers, etc. These interventions can be delivered by health care professionals who do not specialize in alcoholism treatment. Often, a health care professional such as a physician, nurse, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, or a dietitian, whom the patient already trusts, can deliver the brief intervention (4, 13). Therefore, brief interventions can be a cost-effective tool in the prevention and reduction of alcohol abuse. The following steps are generally considered the important components for effective screening and brief interventions for at risk drinking (14): Assess alcohol consumption using a screening tool followed by clinical assessment Advise patients to reduce consumption to moderate levels 7 Agree on individual goals for moderate alcohol consumption or abstinence Assist patients with acquiring the motivations, self-help skills, or supports needed for behavioral change and Arrange follow-up support and repeated counseling, including referrals for further treatment. For more detailed guidance on screening and brief intervention, please refer to the resources provided at the end of this section. C. Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) are characterized by excessive alcohol consumption. The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) classifies AUDs as alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence. The DSM-IV criteria for alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence are set forth below (15, 16): Alcohol abuse A maladaptive pattern of alcohol use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by one (or more) of the following, over a 12-month period: Recurrent alcohol consumption that results in inability to fulfill obligations at home, school or work Recurrent alcohol consumption when it could be physically dangerous (such as driving a car) Recurrent alcohol-related legal problems such as arrests Continued drinking despite interpersonal or social problems that are caused or made worse by drinking. Alcohol dependence A maladaptive pattern of alcohol use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by three (or more) of the following, occurring at any time in the same 12-month period: 1. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following: o A need for markedly increased amounts of the substance to achieve intoxication or desired effect o Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of the substance 2. Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following: o The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance o Use of alcohol to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms 8 3. Alcohol is often consumed in larger amounts or over a longer period than was intended 4. There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control alcohol use 5. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain alcohol, use it, or recover from its effects 6. Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of alcohol use 7. Continued use of alcohol despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by alcohol. D. Biological biomarkers to detect alcohol dependence and alcohol-related diseases The relationship between alcohol and the liver serves as the basis for many tests that are currently used to identify possible alcohol abuse, but elevations may come from liver disease rather than alcohol abuse (12). The most sensitive and widely available test is the serum gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) assay. It is not very specific, therefore, reasons for GGT elevation other than excessive alcohol use need to be eliminated. If elevated at baseline, GGT and other transaminases may also be helpful in monitoring progress and identifying relapse, and serial values can provide valuable feedback to patients after an intervention (8). Other blood tests include the mean corpuscular volume (MCV) of red blood cells, which is often elevated in people with alcohol dependence, and the carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT) assay. The CDT assay is about as sensitive as the GGT and has the advantage of not being affected by liver disease. The CDT is elevated in alcohol dependent individuals and remains elevated for several weeks even after an individual has stopped drinking. It is often used to assess prolonged (weeks) ingestion of high amounts of alcohol (more than 50-60 g/day) (8, 12). Biological markers for recent alcohol ingestion include urine/breath/blood, AlcoPatch, Methanol, Ethylglucuronide and the ratio of 5-hyroxytryptophol to 5-hydroxyindole-3-acetic acid (12). E. Treatment referral, medications and follow-up The role of the health care professional in the care of the patient who abuses or is dependent on alcohol is to identify the problem, offer brief intervention if appropriate, and participate in or refer the patient for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up care. 9 Treatment referral The Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration has developed an online searchable directory of alcohol treatment programs: Substance Abuse Treatment Facility Locator. This directory shows the location of facilities around the country that treat alcohol dependence and alcohol abuse problems. The Locator includes more than 10,000 treatment programs, including residential treatment centers, outpatient treatment programs and hospital inpatient. The Substance Abuse Treatment Facility Locator can be obtained at http://www.findtreatment.samhsa.gov. Medications Three oral (disulfiram, naltrexone, and acamprosate) and one injectable (extended-release injectable naltrexone) medications are currently FDA approved and available to treat alcohol dependence. These medications have been shown to be helpful in reducing drinking, reducing relapse to heavy drinking, achieving and maintaining abstinence, or a combination of these effects (8). According to NIAAA, all approved medications have some efficacy as adjuncts to other treatment modalities in reducing alcohol dependence in clinical trials. Patients who have previously failed to respond to psychosocial approaches alone have been shown to be particularly strong candidates for pharmacological interventions. The choice of medication for treatment will depend on clinical judgment and patient tolerance. Each medication has a different mechanism of action and the patient may respond differently to these medications (8). For additional information on medications please refer to the NIAAA’s Updated 2005 Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician’s guide. A copy of the Clinician’s Guide is included in the folder at the end of this section. Follow-up Once the patient has achieved abstinence and is in recovery, it is important for the health care professional to monitor for relapse. Some reasons for relapse include stopping supportive therapies such as AA, depression, isolation, and anxiety. Health care professionals can encourage adjunct psychosocial support groups and also be aware that patients with anxiety or depression who receive treatment are less likely to relapse. F. Tools for professional education Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician’s Guide U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (Reprinted May 2007, Updated 2005 Edition). Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician’s guide (NIH Publication No. 07-3769). 10 Alcohol Alert – Screening for Alcohol Use and Alcohol-Related Problems U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2005, April). Alcohol Alert – Screening for alcohol use and alcohol-related problems (NIAAA Publication No. 65). Alcohol Alert – Brief Interventions U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2005, July). Alcohol Alert – Brief interventions (NIAAA Publication No. 66). Alcohol Education Center (AEC) (http://www.aeccme.org) An online continuing medical education course has been developed by Dr. Mark Gold for physicians, nurses and other health care providers. Topics covered include alcohol metabolism, blood alcohol levels, tolerance, standard drink information, alcohol abuse and dependence, treatment and relapse, contraindications, potential benefits of moderate beverage alcohol consumption, fetal alcohol syndrome, screening and brief intervention, genetic factors, risk factors, protective factors, age and gender issues, among others. The AEC offers a curriculum of free courses and is a great resource for health care professionals who would like to learn more about alcohol consumption and alcohol abuse. (For more information, please see the handout in the folder at the end of the Section III). Dr. Mark Gold is Donald Dizney Eminent Scholar & Distinguished Professor at the University of Florida McKnight Brain Institute, Departments of Psychiatry, Neuroscience, Community Health and Family Medicine; Chair, Department of Psychiatry, University of Florida College of Medicine. Ensuring Solutions to Alcohol Problems (www.ensuringsolutions.org) Ensuring Solutions is a project of the Center for Integrated Behavioral Health Policy, part of the Department of Health Policy at the School of Public Health and Health Services, The George Washington University Medical Center in Washington, DC. Over the past five years, Ensuring Solutions has: Helped businesses nationwide to demand better alcohol-related services from their health plans. Health plans following these new standards increased the identification of patients with alcohol problems by more than 15 percent in one year, ensuring treatment for tens of thousands of additional patients. Convinced the American Medical Association and the Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services to create new billing codes that encourage primary care physicians to identify and treat people with substance use disorders. Developed new research-based standards for the identification and treatment of substance use disorders. These standards were endorsed by the National Quality Forum in 2007. 11 Created an online technical assistance program to help repeal insurance laws that discourage emergency room doctors from identifying patients with alcohol-related problems. Since 2002, this resource has helped to repeal laws in nine states and the District of Columbia. Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) Resource (www.sbirt.samhsa.gov/index.htm) The purpose of the SBIRT Web site is to provide a single, comprehensive repository of SBIRT information. This information includes training manuals, online resources, links to organizations and publications, and a list of references. The site includes links to various SBIRT-related curricula, online resources, organizations, and publications as well as detailed information on Coding for Screening and Brief Intervention reimbursement. G. Supplemental Resources For a full description of the following agencies and associations, please refer back to Section I, Supplemental Resources. American Academy of Family Physicians Four Screening Steps (www.aafp.org) American Academy of Nurse Practitioners (AANP) (www.aanp.org) American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) (www.aap.org) American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) (www.aapa.org) American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) (www.acog.org) American Medical Women’s Association (AMWA) (www.amwa-doc.org) American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) (http://www.asam.org) Distilled Spirits Council of the United States (www.distilledspirits.org) Government Links: http://www.distilledspirits.org/govt_sites Industry Responsibility Links: http://www.discus.org/responsibility/ Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) (http://www.madd.org) National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) (http://www.niaaa.nih.gov) NIAAA Clinician’s Guide: Helping patients who drink too much http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/guide.pdf 12 http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/PocketGuide/pocket.pdf PowerPointTM Slideshow (80 slides) on the Clinician’s Guide http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/practioner/CliniciansGuide2005/UsingNIAAAClinici ansGuide.ppt National Medical Association (NMA) (www.nmanet.org) Nutrition Educators of Health Professionals a Dietetic Practice Group of the American Dietetic Association (NEHP/ADA) http://www.nehpdpg.org/ – NEHP/ADA http://www.eatright.org/cps/rde/xchg/ada/hs.xsl/career_dpg51_ENU_HTML.htm http://www.eatright.org – American Dietetic Association Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) (www.stfm.org) Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) (www.samhsa.gov) Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) Resource www.sbirt.samhsa.gov/index.htm SAMHSA: Substance Abuse Treatment Facility Locator http://www.findtreatment.samhsa.gov SAMHSA: National Clearinghouse for Alcohol and Drug Information (NCADI) http://ncadi.samhsa.gov/about/aboutncadi.aspx The Century Council (www.centurycouncil.org) G. References For copies of these references, please contact adulttoolkit@discus.org. 1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2005). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005. 6th Edition. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. 2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (Updated March 2000, Printed 1995). The physicians’ guide to helping patients with alcohol problems (NIH Publication No. 95-3769). 13 3. Moyer, A., Finney, J. W., Swearingen, C. E., Vergun, P. (2002). Brief interventions for alcohol problems: A meta-analytic review of controlled investigations in treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking populations. Addiction, 97(3), 279-292. 4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2005, July). Alcohol Alert – Brief interventions (NIAAA Publication No. 66). 5. American Medical Women’s Association. Press release: New survey shows that majority of doctors talk to their patients about alcohol. Alexandria, VA: American Medical Women’s Association; January 11, 2005 6. Multi-sponsor Surveys, Inc. The Gallup Organizations (2001). New Gallup Survey on Alcohol Equivalence. 7. Hui, Y. H. (Ed.). (1992). Encyclopedia of food science and technology (Vols. 1-4). New York: Wiley. 8. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (Reprinted May 2007, Updated 2005 Edition). Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician’s guide (NIH Publication No. 07-3769). 9. Gentry, T. R., et al. (2000). Workshop on the in vivo pharmacokinetics of alcohol. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 24(4), 399-427. 10. Kalant, H., LeBlance, A. E., Wilson, A., Homatidis, S. (1975). Sensorimotor and physiological effects of various alcoholic beverages. CMA Journal, 112, 953-958. 11. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2005, April). Alcohol Alert – Screening for alcohol use and alcohol-related problems (NIAAA Publication No. 65). 12. Gold, M. S. (2008). Alcohol, alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence. Continuing Medical Education Resource. Sacramento, CA. 13. Moyer, A., Finney, J. W. (2004/2005). Brief Interventions for alcohol problems: factors that facilitate implementation. Alcohol Research & Health, 28(1), 44-50. 14. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2004, April). Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse (AHRQ Publication No. 04-IP010). 14 15. Stewart, S. H., Connors, G. J. (2004/2005). Screening for alcohol problems: What makes a test effective? Alcohol Research & Health, 28(1), 5-16. 16. American Psychiatric Association. (2005). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 15