The Cost of Early Termination

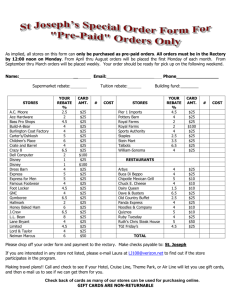

advertisement

Page 1 LEXSTAT 1-6 DEBTOR-CREDITOR LAW § 6.03 Debtor-Creditor Law Copyright 2009, Matthew Bender & Company, Inc., a member of the LexisNexis Group. PART I Consumer Credit CHAPTER 6 The Cost of Credit 1-6 Debtor-Creditor Law § 6.03 § 6.03 The Cost of Early Termination [1] Overview A distinct form of overcharge often appears when credit is retired early by prepayment of the debt (including by refinancing) or when a debt matures early because of default and acceleration. Since the amount of interest due is in part a function of the time the credit is outstanding, shortening the time should, as a matter of logic and fairness, reduce the amount of interest the borrower pays. But that may not always happen. The creditor may impose hidden charges, consisting of any unearned amount of insurance premiums and precomputed interest that it retains upon the early termination of credit. The windfall that a creditor would receive if it could retain unearned charges upon prepayment or acceleration of precomputed debt has been widely recognized, and almost all state consumer credit statutes have long required the rebate of unearned interest and insurance charges. Failure to give those rebates, or to calculate them correctly, gives rise to usury or overcharge claims.n1 As is discussed in this chapter, there are numerous exceptions and limitations to this policy. [2] When Are Rebates Required? [a] Precomputed Charges One of the two key words in determining when rebates are necessary is "unearned." Issues about the proper rebate of interest should arise only with respect to precomputed credit, because, by definition, interest is added to the debt only as it is earned in an interest-bearing contract.n2 Thus, as a general rule, there is no unearned interest involved in interest-bearing credit, though, as is discussed below, that is not an absolute. A precomputed transaction, in contrast, folds into the borrower's legal obligation at the outset all the interest to be earned over the originally scheduled life of the loan. As payments are made, they are subtracted from the "total of payments" and not allocated between interest and principal,n3 so at any point prior to the scheduled maturity, the remaining debt (the sum of the remaining payments due) will include some interest not yet earned. It is primarily this context in which rebate issues arise. However, rebate issues can also arise in interest-bearing transactions, as contract interest may not be the only type of charge imposed. Most commonly, both precomputed and interest-bearing loans may contain other Page 2 1-6 Debtor-Creditor Law § 6.03 charges which are priced in relation to time, such as credit insurance premiums. These will need to be rebated upon early termination.n4 The second key word in determining when a rebate is required is "early." For example, if a borrower defaulted on the last two payments of a loan, which was scheduled to mature on April 1, 1994, but the creditor did not file a collection action until June 1, 1994, there will be no rebate issues. Since the loan went to (and past) maturity, all the precomputed interest would have been fully earned, as would any credit insurance premiums.n5 Also related to the "early termination" prerequisite is how rebates are to be handled when the transaction is involuntarily terminated prior to scheduled maturity. In the event of default, the loan may mature early through acceleration. Involuntary early termination of a consumer credit transaction may trigger state and federal rebate requirements. Finally, the federal law and most state laws typically do not require rebates for "partial prepayments."n6 These are early payments which are too small to retire the consumer's total debt. Advocates representing borrowers who have made partial payments in precomputed transactions should check the language of both the state usury statutes and the credit contract to see how partial payments are treated. [3] What Charges Are Subject to Rebate? In precomputed transactions, by definition, there will be unearned interest when the loan is prepaid and so a refund is necessary. In contrast, generally there is no unearned interest to rebate in an interest-bearing transaction when it is properly amortized. However, it is nonetheless necessary to check the creditor's accounting on interest-bearing loans, too. As is discussed elsewhere in this volume, creditors usually charge debtors numerous fees in addition to the stated contract interest.n7 Creditors typically claim that these fees are earned at the consummation of the credit contract and need not be rebated because they are unrelated to the term of the credit. The validity of this argument depends on the particular type of fee which has been assessed and the language of the controlling statute. The argument that a fee is earned at the outset of a credit transaction makes no sense in the case of fees that are clearly related to the term of credit. Credit insurance premiums, for example, usually vary with the term of credit, and the difference between a two-year premium and a one-year premium is unearned if prepayment occurs after one year.n8 The logical relationship between a fee and the term of credit is, however, only part of the rebate story. As with other usury issues, whatever fee the controlling statute says is rebatable is rebatable, and whatever fee the statute excuses from rebates need not be rebated, common sense notwithstanding. One potential area of dispute is whether the federal or a relevant state law governing the transaction requires the rebate of points, service charges, origination charges, or other one-time fees charged at the time the loan is consummated.n9 State statutes differ on this issue, some deeming points or similar prepaid finance charges as "nonrefundable" or clearly stating that they are to be considered earned at consummation. Other statutes are silent on this matter. Where not expressly addressed, a mandate to rebate points may nevertheless follow directly from standard statutory rebate language. Page 3 1-6 Debtor-Creditor Law § 6.03 In the absence of any controlling statute or case law, the need to rebate points may depend on the underlying economic validity of the creditor's argument that they are earned at the time of loan consummation.n10 This argument depends on the existence of some separate service which the creditor provides at the beginning of a credit transaction and for which it may claim immediate compensation. Some courts considering the nature of points and similar fees have found no such separate service and have held instead that these fees merely constitute profit or compensation for overhead expense.n11 Additional authority for this proposition is found in generally accepted accounting principles, as well.n12 With respect to the rebate of points, a particularly interesting issue is whether points are "interest" for purpose of the federal rebate statute. It is by no means clear that TIL definitions do--or should--apply here, for the rebate statute is not part of TILA despite its location in the code books. An argument can be made that, since the federal rebate statute is not part of TIL, the federal common law definition of "interest" should be the relevant one. Using this body of law as the relevant definition, then, would mean that a great many kinds of charges, such as points, would be "interest charges" subject to the federal rebate mandate. As with state laws, there remains the question of whether a given item in that broad category of charges is "unearned." It is important to keep in mind other theories to attack abusive use of points as well. Where not explicitly sanctioned, a failure to rebate points might be argued as a prepayment penalty.n13 If the points are excessive, as some high-rolling mortgage lenders imposed in the mid-1980s (25 to 40 points),n14 borrowers might also challenge such nonrefundable fees as unconscionable,n15 particularly in the context of refinancings.n16 [4] Calculating Rebates [a] Initial Steps in Calculating the Rebate The first step in any rebate calculation is to determine the precise date as of which the rebate must be calculated. If a loan is prepaid, either directly by the borrower or through refinancing, the controlling date will be the date of prepayment, although as discussed subsequently, that date may be rounded to the nearest regular payment date preceding or following the actual date of prepayment. If a debt is matured through acceleration rather than voluntary prepayment, however, determining the date when a rebate must be credited is more complicated.n17 In some states, acceleration is simply treated as a form of prepayment and the controlling date for rebate calculations is the date on which the creditor accelerates the debt.n18 Some courts have held that rebates are required when a post-repossession sale is held.n19 In other states, however, acceleration is not viewed as terminating the credit, and the creditor continues to earn interest until some later date, such as the date the creditor files an action on the debt or the date of final judgment on the debt.n20 If the date of filing or the judgment date, as the case may be, is later than the date on which the debt was originally scheduled to terminate, the creditor will have earned all the interest due under the contract, and no rebate will be required. The next complication in calculating the time that a precomputed loan has been outstanding is that contractually interest is "earned" and payments are due at specific intervals, usually monthly, during the term of the loan, but prepayments and accelerations generally do not occur exactly on a payment date. Rather than giving the borrower a partial rebate for the days remaining in the payment interval,n21 lenders have traditionally rounded up to the next payment date (rarely back to the previous payment date). The practice of rounding payment intervals in a lender's favor has traditionally been sanctioned by state law. As consumers and regulators have become more sophisticated, however, more and more statutes have pro- Page 4 1-6 Debtor-Creditor Law § 6.03 hibited the rounding of intervals in the creditor's favor during the first fifteen days of the payment period,n22 and improper rounding has been challenged in court.n23 Specific statutory rounding rules, even if they still favor creditors,n24 provide clear standards against which a creditor's calculations may be measured. Creditors who claim excess interest through improper rounding will be charging illegal hidden interest.n25 [b] Rebate Formulae [i] Determining Which Formula to Use Once the particular charges that are subject to rebate are identified and the duration of the credit has been determined, the final step in computing the amount of the rebate is to apply to these figures one of the three rebate formulae which are generally used: the pro rata formula, the actuarial formula, or the Rule of 78. For transactions consummated prior to September 30, 1993, the appropriate formula will be a question of state law. However, for consumer credit transactions with terms longer than 61 months consummated after that date, federal law now prohibits the use of the Rule of 78. It requires instead the use of a formula at least as favorable to the borrower as the actuarial method.n26 This federal law will preempt any contrary state law. After 1994, certain closed-end, high cost home equity loans are also subject to federal rebate rules.n27 But for transactions consummated prior to the effective date of these federal statutes, and for transactions not subject to it, the appropriate rebate formula remains a matter of state law.n28 [A] Pro Rata Rebates The simplest but least used rebate formula is the pro rata method. This formula assumes that interest is earned in direct proportion to the time that a loan or credit has been outstanding. For example, if a prepayment occurs four months into the term of a precomputed loan that had been scheduled to be repaid in twelve months, the pro rata method proves that 4/12 of the interest has been earned. Consequently, the remaining 8/12 of the interest is unearned and must be rebated. If the total finance charge subject to rebate had been $1,000, then 8/12 x $1,000 = $666.67 should be rebated to the consumer. The pro rata rebate method is simple to apply, but it is statistically very crude because it fails to consider the effect of a declining principal balance on the earning of interest. Not because of its statistical inaccuracy, but because the pro rata method yields larger rebates for borrowers than other methods, it is rarely used. Statutes requiring pro rata rebates do, nevertheless, crop up at times, particularly for those rebates required when a creditor accelerates a debt because of default or some other contingency,n29 or in the event of a quick-flip on a loan.n30 [B] Rule of 78 The Rule of 78 is nothing more than a shorthand formula designed to approximate the results of an actual amortization with a single, simple five-step formula, which is all the more efficient because it can be applied to all transactions irrespective of term or interest rate. There is, however, a hitch in this shorthand approximation: It has an inherent bias in the creditor's favor. There will always be a smaller rebate to the consumer when the Rule of 78 is used than when the actuarial method is used, so the borrower always loses.n31 As discussed above, the use of the Rule now is prohibited in all precomputed consumer credit transactions with terms longer than 61 months consummated after September 30, 1993.n32 [C] Actuarial Rebates Page 5 1-6 Debtor-Creditor Law § 6.03 The most accurate and the fairest way to balance creditor and debtor interests in a rebate calculation is to determine the actuarial interest that the creditor has earned at the time of prepayment and to refund to the borrower the difference between the total contract interest and this actuarially earned amount.n33 Generally accepted accounting principles consider this the economic reality.n34 A special rebate calculation issue arises under actuarial "split" rate usury statute, which apply one interest rate to part of the outstanding balance and another, usually a lower rate, to the rest. State law and regulations must be consulted to determine which actuarial rebate is correct. However, if the applicable statute does not specify the type of "actuarial" rebate, consumer advocates should argue that the very existence of the split rate statute constitutes a statutory specification that interest may only be earned in accordance with a split rate amortization pattern.n35 [5] Proving Rebate Violations Are Illegal Charges [a] Usury Upon a Contingent Event Until the 1960s, it was common for usury statutes to neglect the issue of rebates upon the early termination of precomputed debt. In essence, the courts reasoned that a contract which would not have been usurious if its anticipated payment schedule had been met could not be made usurious by some "contingency," such as the "voluntary" action of the debtor in prepaying or defaulting on the debt. It is critical for consumer advocates to recognize that this rule against the existence of usury in contingencies is simply a rule of construction developed by courts interpreting statutes that were silent on the need for rebates.n36 If a statute specifically requires the rebate of unearned interest or premiums, as do almost all modern statutes regulating precomputed consumer credit, then the failure of the creditor to provide such rebates triggers whatever remedies that statute provides for in the event its terms regarding allowable charges are violated. The rule against usury through contingencies nevertheless continues to affect some consumer transactions. [b] Intent to Collect Unearned Charges: What Constitutes "Charging," "Receiving," or "Contracting For" Unearned Charges? Under some consumer credit statutes, specific remedies are authorized wherever finance charges (or simply charges) in excess of that allowed are charged,n37 or, more generally, where provisions of the act are violated.n38 Any time the statute provides for a specific remedy for imposing charges in excess of that allowed, a provision requiring rebates should be considered to be encompassed by that language.n39 In general, there are two ways in which a creditor may violate usury law rebate requirements: Either the creditor can provide a contract, which on its face fails to provide for the appropriate rebate, or it can neglect in actual practice to give a rebate which it is both contractually and statutorily required to give. Where intent is required, demonstrating a usury violation in the first situation may be considerably easier than in the second because the contract itself can show the creditor's intent. In many jurisdictions, it is usurious merely to "contract for" usurious payments. If a credit contract properly provides for a rebate upon the early termination of a precomputed debt, the next question is whether, when the prepayment or acceleration finally occurs, the creditor actually gives the rebate properly. Statutorily, the issue is typically whether the creditor "charged" or "collected" usurious interest, and a significant number of cases have focused on this point. [c] Special Issues Regarding Remedies for Violations of the Federal Rebate Statute Page 6 1-6 Debtor-Creditor Law § 6.03 The federal rebate statute does not include any provisions for a specific remedy in the event a creditor violates it. Nonetheless, there are several viable theories which the consumer could assert in the event a creditor violated the statute. [i] Truth in Lending Irrespective of whether it is considered part of TIL or not, a violation of the federal rebate statute probably does not directly lead to a viable claim for private TIL remedies.n40 It may, however, lead indirectly to a TIL violation. In brief, in the event the creditorn41 refinances the loan, and calculates the prior loan's payoff in violation of the statute, either by failing to give rebates or by using the Rule of 78 when the actuarial method is required, the new loan will include an "unearned portion of the old finance charge that is not credited to the obligation."n42 Under TIL rules, that is to be considered part of the finance charge in the new loan.n43 Thus, the disclosed amount financed, finance charge, and APR on the new loan all will be inaccurately disclosed,n44 and those violations, in turn, lead to TIL statutory damages as well as actual damages.n45 [ii] UDAP Failure to comply with the rebate law should also state a UDAP claim, where the transaction and lender are subject to the statute: The amount of the improperly calculated rebate would be actual damages.n46 [iii] Contract Law Common law contract principles may also be invoked to seek a remedy, as applicable law is an implied term of every contract.n47 [6] Prepayment Penalties In its simplest form, a prepayment penalty is a fee that a borrower is contractually obligated to pay if he or she chooses to pay off a debt prior to its scheduled retirement date. In the absence of statute or contract authorization, common law may prohibit prepayment of a debt.n48 However, in the consumer credit context, most state laws require that borrowers be allowed to prepay their debts and often limit or prohibit prepayment penalties.n49 Such statutory provisions are usually closely associated with the state's rebate requirements because the failure to provide a proper rebate upon the prepayment of a precomputed debt is essentially a form of prepayment penalty.n50 However, rebate requirements and prepayment penalty prohibitions are not interchangeable. The most obvious difference is that statutes prohibiting prepayment penalties typically are invoked when debt is retired through voluntary prepayment, while rebate requirements apply to precomputed debt regardless of whether it is prepaid, accelerated, or otherwise matured.n51 The new federal legislation regarding high rate mortgages addresses this issue of prepayment penalties. For most covered loans,n52 no prepayment penalties are permitted at all, and use of any method of rebate less favorable than the actuarial rule is specifically defined to constitute a prepayment penalty.n53 There is one very narrow, complex exception.n54 Finally, the laws of most states forbid prepayment penalties in consumer transactions, but borrowers' attorneys should be aware that these prepayment penalty prohibitions have been overridden in the case of some mortgage loans.n55 Specifically, if permitted by a loan contract, state and national banks may impose prepayment penalties on adjustable-rate mortgage loans,n56 and federally chartered savings and loan institutions may impose prepayment penalties on both fixed and variable rate mortgage loans.n57 Up until July 1, 2003, Page 7 1-6 Debtor-Creditor Law § 6.03 the Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS) allowed "housing creditors," defined as non-depository lenders who regularly make loans or credit sales secured by residential realty or mobile homes, to impose prepayment penalties in loans that fell under the Alternative Mortgage Transactions Parity Act.n58 Effective July 1, 2003, however, OTS amended its rules to no longer authorize these lenders to impose fees for prepayment.n59 As a result, these creditors are subject to any state restrictions on prepayment penalties. Further, non-depository lenders who regularly make loans or credit sales secured by residential realty or mobile homes may impose prepayment penalties in loans that fall under the Alternative Mortgage Parity Act.n60 However, federal credit unions are specifically prohibited from receiving prepayment penalties,n61 as are any lenders making FHA-insured mortgage loans.n62 Another limitation is that OTS forbids collection of prepayment penalties by federal thrifts when they accelerate mortgage notes pursuant to due-on-sale clauses.n63 A creditor may attempt to evade a prohibition on prepayment penalties by creative labeling of the charge. For example, one bank waived the borrower's obligation to pay closing costs, as long as the borrower did not prepay the obligation for three years. Maryland's highest court held that, because the closing cost charge was imposed on the borrower only in the event of prepayment, it was a prepayment penalty no matter how it was labeled.n63.1 [7] Preemptive Effect of the New Federal Consumer Protection Statutes In some cases, the federal rebate statuten64 and the high cost mortgage statuten65 will provide greater protections to borrowers than they would otherwise have under state or other federal law. In other states, though, state law may still provide greater protection. The high cost mortgage statute is explicit about preemption. Even in the limited circumstances where a creditor is permitted to impose a prepayment penalty in a covered loan under that statute, it can only do so if otherwise applicable law also permits it.n66 Further, the new disclosure and substantive prohibitions do not affect state law "except to the extent that those State laws are inconsistent, and then only to the extent of the inconsistency,"n67 by which Congress intended "to allow states to enact more protective provisions than those in this legislation." The federal rebate statute included no specific preemption language. However, it, too, should not preempt state laws more protective of the consumer since consumer protection statutes are to be liberally construed to effectuate their purpose.n68 Legal Topics: For related research and practice materials, see the following legal topics: Banking LawFederal ActsGeneral OverviewBanking LawNational BanksInterest & UsuryGeneral OverviewBanking LawNational BanksInterest & UsuryInterestBanking LawNational BanksInterest & UsuryUsury LitigationContracts LawDebtor & Creditor Relations FOOTNOTES: (n1)Footnote 1. See, e.g., Circle v. Jim Walter Homes, Inc., 479 F. Supp. 39 (W.D. Okla. 1979) , aff'd, 654 F.2d 688 (10th Cir. 1981) ; Clyde v. Liberty Loan Co., 249 Ga. 78, 287 S.E.2d 551 (1982) ; G.A.C. Fin. Corp. v. Hardy, 232 Ga. 632, 208 S.E.2d 453 (1974) . (n2)Footnote 2. At any given time, the amount due on an interest-bearing contract is the unpaid principal balance plus accrued interest. See, e.g., In re Curtis, 83 B.R. 853 (Bankr. S.D. Ga. 1988) ; Myles v. Resolution Trust Corp., 787 S.W.2d 616 (Tex. Ct. App. 1990) (no usury contracted for in acceleration clause of interest-bearing contract). (n3)Footnote 3. See generally James H. Hunt, The Rule of 78: Hidden Penalty for Prepayment in Consumer Credit Transactions, 55 B.U. L. Rev. 331, 331 n.2 (1975). Page 8 1-6 Debtor-Creditor Law § 6.03 (n4)Footnote 4. See § 6.03[3] infra. (n5)Footnote 5. There may be another issue, however, as to how the creditor calculated any interest due after maturity and before the legal action. Some contracts provide for lower post-maturity rates (though rarely these days), others provide for continuing at the original rate, and yet others provide for a higher "default" rate. Some predatory home equity lenders have contracted for default rates of 36% to 42% on fully secured loans. As a consequence, Congress limited default rates on high cost mortgages. Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act, codified at 15 U.S.C. § 1639(d). Some state statutes may regulate default rates, as well. See, e.g., Ala. Code § 5-18-15(j) (small loan maximum interest reduced to 8% six months after maturity). (n6)Footnote 6. See, e.g., 15 U.S.C. § 1615(a); Neb. Rev. Stat. § 45-137(2)(c) (1988). But see Cal. Fin. Code §§ 22480(a)(3), 24480(a)(3) (West 1981 and Supp. 1994) (recomputation required for partial prepayment of three or more installments). (n7)Footnote 7. See § 6.05 infra. (n8)Footnote 8. See Varner v. Century Fin. Co., 738 F.2d 1143 (11th Cir. 1984) ; Clyde v. Liberty Loan Co., 287 S.E.2d 551 (Ga. 1982) (maintenance charges and credit insurance premiums must be rebated if unearned); Brown v. Associates Fin. Servs. Corp., 346 S.E.2d 873 (Ga. Ct. App. 1986) . But note that some types of credit may charge for credit insurance on a monthly installment basis, as is typically the case with credit cards. (n9)Footnote 9. For a discussion of points as interest, see § 6.05[2][b] infra. (n10)Footnote 10. Cf. In re Tucker, 74 B.R. 923 (Bankr. E.D. Pa. 1987) (though persuasive authority and public policy suggest a "service charge" should be rebated, the controlling statute is clear that no such rebate is required). (n11)Footnote 11. See § 6.05[2][b] infra. (n12)Footnote 12. See FASB Statement No. 91, Accounting for Nonrefundable Fees and Costs Associated With Originating or Acquiring Loans and Initial Direct Costs of Leases (effective for fiscal years beginning after Dec. 15, 1987). See generally FASB Accounting Standards, § L20 (1993/94 ed.). (n13)Footnote 13. See § 6.03[6] infra. Cf. In re Jungkurth, 74 B.R. 323 (Bankr. E.D. Pa. 1987) (absent statutory authorization, Rule of 78 is a prepayment penalty). Note that non-depository lenders who regularly make loans or credit sales secured by residential realty or mobile homes may impose prepayment penalties in loans that fall under the Alternate Mortgage Parity Act. 12 U.S.C. § 3801. See § 6.02[7] supra; National Home Equity Mortg. Ass'n v. Face, 239 F.3d 633 (4th Cir. 2001) , cert. denied, 534 U.S. 823, 122 S. Ct. 58, 151 L. Ed. 2d 26 (2001) ; McCarthy v. Option One Mortg. Corp., 2001 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 22711 (N.D. Ill. Feb. 11, 2001) (non-federally chartered housing creditor can charge prepayment penalty, but only if it complies with OTS regulations); Shinn v. Encore Mortg. Servs., 96 F. Supp. 2d 419 (D.N.J. 2000) (housing creditor that complied with OTS regulations could charge prepayment penalty notwithstanding state law restrictions). (n14)Footnote 14. E.g., First American Mortgage Company and Landbank Equity, two major multi-state lenders, both of which eventually went into bankruptcy, leaving their loans in the hands of other lenders which had purchased them on the secondary mortgage market. (n15)Footnote 15. See, e.g., Williams v. E.F. Hutton Mortg. Corp., 555 So. 2d 158 (Ala. 1989) . (n16)Footnote 16. See § 6.04 infra. (n17)Footnote 17. Of course, accelerating an interest-bearing debt, instead of a precomputed debt, will not require any rebates, as there is no unearned interest to rebate. See In re Curtis, 83 B.R. 853 (Bankr. S.D. Ga. 1988) ; Myles v. Resolution Trust Corp., 787 S.W.2d 616 (Tex. Ct. App. 1990) (no usury contracted for in acceleration clause of interest-bearing contract). Page 9 1-6 Debtor-Creditor Law § 6.03 (n18)Footnote 18. See, e.g., Iowa Code Ann. § 537.2510(6) (West 1987) (if judgment is obtained, rebate is calculated as of date of acceleration); N.Y. Pers. Prop. Law § 408(6) (McKinney 1992); N.C. Gen. Stat. § 25A-32 (1986) (15 days after acceleration); Pa. Stat. Ann. tit. 69, § 622B (1994). (n19)Footnote 19. Union Trust Co. v. Tyndall, 428 A.2d 428 (Md. 1981) ; First Va. Bank v. Settles, 588 A.2d 803 (Md. Ct. App. 1991) . (n20)Footnote 20. For example, both the 1968 and 1974 versions of the Uniform Consumer Credit Code (UCCC) provide that "if the maturity is accelerated for any reason and judgment is entered, the consumer is entitled to the same rebate as if payment had been made on the date judgment is entered." UCCC §§ 2.210(8), 3.210(8) (1968); UCCC § 2.510(7) (1974). See also Hawaii Rev. Stat. § 408-15(f) (1985); Neb. Rev. Stat. § 45-137(2)(c) (1988); W. Va. Code § 46A-3-111. (n21)Footnote 21. Such partial rebates may be required only for prepayments in the first 30 or 60 days of a loan. See, e.g., Ohio Rev. Code Ann. §§ 1321.13 (Baldwin 1993) (small loans); 1321.57 (second mortgages) (if payment is made before first installment is due, lender may keep 1/30 of monthly finance charge per day loan was outstanding). (n22)Footnote 22. See, e.g., Ala. Code § 5-19-4 (1981 and Supp. 1993); Neb. Rev. Stat. § 45-137(2)(c) (1988); Ohio Rev. Code Ann. §§ 1321.13, 1321.57 (1998); S.C. Dep't of Consumer Affairs 3.210-7609 Consumer Cred. Guide (CCH) P 98,318 (Oct. 21, 1976) (one day cannot be treated as one month for rebate purposes); see also Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. Ann. § 5069-3.15(6)(b) (1987) (pro rata earnings for odd days when prepayment is not on installment date). (n23)Footnote 23. Compare Steele v. Ford Motor Credit Co., 783 F.2d 1016 (11th Cir. 1986) (truth in lending case), with In re Jones, 79 B.R. 233 (Bankr. E.D. Pa. 1987) (state law permits use of Rule of 78 and rounding forward to allow a fraction of a month to be considered a full month). See also Webster v. International Harvester Credit Corp., 51 Ohio App. 2d 192, 367 N.E.2d 924, 5 Ohio Op. 3d 332 (1977) . (n24)Footnote 24. For example, the Ohio RISA arbitrarily requires rounding in the borrower's favor only in the first ten days of the payment interval. See Webster v. International Harvester Credit Corp., 51 Ohio App. 2d 192, 5 Ohio Op. 3d 332, 367 N.E.2d 924 (1977) . (n25)Footnote 25. Cf. Steele v. Ford Motor Credit Co., 783 F.2d 1016 (11th Cir. 1986) (hidden finance charge under Truth in Lending Act). (n26)Footnote 26. 15 U.S.C. § 1615. Consumer credit transactions have the same definition that they do in Truth in Lending, except that "creditor" includes any assignee. 15 U.S.C. § 1615(d)(3). (n27)Footnote 27. Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act, codified at 15 U.S.C. § 1639. See Ch. 2 supra. (n28)Footnote 28. See, e.g., Zwayer v. Ford Motor Credit Co., 279 Ill. App. 3d 906, 216 Ill. Dec. 585, 665 N.E.2d 843 (1996) (where court held that rebates computed by the Rule of 78s are not allowed where contract terms are ambiguous). Certain transactions may be subject to other federal law which may also prohibit the use of the Rule of 78, such as federally related loans secured by first liens on mobile homes. See 12 C.F.R. § 590.4 (1994). (n29)Footnote 29. See, e.g., Walter E. Heller & Co. v. Mall, Inc., 267 F. Supp. 343 (E.D. La. 1967) (pro rata refund of discount interest upon acceleration under Louisiana law); Varner v. Century Fin. Corp., Inc., 253 Ga. 27, 317 S.E.2d 178 (1984) (interpreting Off. Code Ga. Ann. § 7-4-2(b)(1) (effective Mar. 1, 1983)). (n30)Footnote 30. E.g., Ala. Code § 5-19-4(d) (pro rata rebate if refinanced by same creditor or affiliate within 90 days). Page 10 1-6 Debtor-Creditor Law § 6.03 (n31)Footnote 31. Bonker, The Rule of 78, XXXI Journal of Finance 877, 885 (No. 3, June 1976); Hunt, The Rule of 78: Hidden Penalty for Prepayment in Consumer Credit Transactions, 55 B.U. L. Rev. 331 (1975). See § 6.03[3] supra. (n32)Footnote 32. 15 U.S.C. § 1615(d). Contrary state law will be preempted. For an explanation of how to calculate a Rule of 78 rebate, see National Consumer Law Center, The Cost of Credit: Regulation and Legal Challenges § 5.6.3.3.2 (2d ed. 2000). (n33)Footnote 33. Even prior to the 1992 federal rebate statute, actuarial rebates were frequently required by state statutes and federal regulations, especially for contracts with longer terms and high principal amounts, because of the Rule of 78 inaccuracy for such transactions. (n34)Footnote 34. James H. Hunt, The Rule of 78: Hidden Penalty for Prepayment in Consumer Credit Transactions, 55 B.U. L. Rev. 331 (1975). (n35)Footnote 35. For how to calculate actuarial rebates, see National Consumer Law Center, The Cost of Credit: Regulation and Legal Challenges National Consumer Law Center, Unfair and Deceptive Acts and Practices §§ 2.2, 2.3 (5th ed. 2001 and Supp.). (n36)Footnote 36. See B.F. Saul Co. v. West End Park N., Inc., 250 Md. 707, 246 A.2d 591 (1968) (distinguishing loans to which rebate statute applies). (n37)Footnote 37. E.g., Ala. Code § 5-19-19 (consumer credit code); Iowa Code § 537.5201(2), (3) (consumer credit code). (n38)Footnote 38. E.g., Mich. Comp. Laws § 445.868 (RISA). (n39)Footnote 39. Since failure to rebate unearned interest results in excess charges, that should trigger any remedy authorized for excess charges. For such statutes, the question may be whether the excess was "charged," or whatever the operative verb in the statute is. (n40)Footnote 40. Civil liability applies to violations of Parts B, D and E of TIL. 15 U.S.C. § 1640. The rebate statute was codified in Part A, 15 U.S.C. § 1615. (n41)Footnote 41. The rebate statute defines creditor by reference to TIL's definition, but specifically includes assignees as creditors, as well. 15 U.S.C. § 1615(d). (n42)Footnote 42. Reg. Z, 12 C.F.R. § 226.20(a). See, e.g., Steele v. Ford Motor Credit Co., 783 F.2d 1016 (11th Cir. 1986) . See generally Ch. 1 supra. Note that this would also be the case when a creditor used the rule in violation of any other applicable statute. See Steele, supra. (n43)Footnote 43. Reg. Z, 12 C.F.R. § 226.20(a). See, e.g., Steele v. Ford Motor Credit Co., 783 F.2d 1016 (11th Cir. 1986) . See generally Ch. 1 supra. Note that this would also be the case when a creditor used the rule in violation of any other applicable statute. See Steele, supra. (n44)Footnote 44. That assumes, of course, that the creditor included the full payoff balance of the prior loan in the amount financed on the new loan. It is unlikely that a creditor would go to the trouble of separating out an illegal overcharge to properly account for it in its TIL calculations. Even if it did so, arguably there is still a TIL violation. TIL requires that disclosures reflect the legal obligation, Reg. Z, 12 C.F.R. § 226.17(c). At least with respect to the finance charge, the legal obligation is to pay charges in accord with applicable law. Applicable law says that the consumer should not have to pay the excess charge at all, irrespective of whether denominated finance charge or amount financed, thus, all the financial disclosures would be skewed because the total loan should be less. See In re Brown, 134 B.R. 134 (Bankr. E.D. Pa. 1991) ; see Ch. 1, § 1.05[2][c], [e][ii] supra. (n45)Footnote 45. 15 U.S.C. § 1640; see Ch. 1, § 1.10[2], [3] supra; National Consumer Law Center, Truth in Lending §§ 8.5, 8.6 (5th ed. 2003). Page 11 1-6 Debtor-Creditor Law § 6.03 (n46)Footnote 46. For a discussion of scope issues under UDAP statutes, see National Consumer Law Center, Unfair and Deceptive Acts and Practices §§ 2.2, 2.3 (4th ed. 1997 and Supp.). For a discussion of UDAP damages, see § 4.06 supra. (n47)Footnote 47. 17A Am. Jur. 2d Contracts § 381. (n48)Footnote 48. E.g., C.C. Port, Ltd. v. Davis-Penn Mortgage Co., 61 F.3d 288 (5th Cir. 1995) (Texas law); Metropolitan Life Ins. Co. v. Strnad, 876 P.2d 1362 (Kan. 1994) . E.g., Norwest Bank v. Blair Road Assocs., 252 F. Supp. 2d 86, 97 (D.N.J. 2003) ; MONY Life Ins. Co. v. Paramus Parkway Bldg., Ltd., 834 A.2d 475 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. 2003) (commercial loan); Westmark Commercial Mortgage Fund IV v. Teenform Assocs., 827 A.2d 1154 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. 2003) (commercial loan). (n49)Footnote 49. E.g., Del. Code tit. 6, § 4322 (RISA: right to prepay and receive rebate of unearned interest); Md. Code Ann. Com. Law § 12-308 (consumer loan law); Miss. Code § 63-19-47 (MVRISA: same); Garver v. Brace, 47 Cal. App. 4th 995, 55 Cal. Rptr. 2d 220 (1996) (prohibitions and limitations in Cal. Civ. Code § 2954.9(b) against prepayment penalty in mortgages on owner-occupied residential real property is extended to include the situation where the borrower builds a home on the property after the loan is executed, but before the prepayment fee is paid). See also Nelson v. Associates Fin. Servs. Co., 253 Mich. App. 580, 659 N.W.2d 635 (Mich. Ct. App. 2002) (construing Mich. Comp. Laws §§ 438.31 and 438.31c to place cap on prepayment penalties for certain deregulated first mortgage loans); Glukowsky v. Equity One, Inc., 360 N.J. Super. 1, 821 A.2d 485 (App. Div. 2003) (New Jersey law prohibits prepayment penalty; OTS regulation preempting state prepayment penalty laws is invalid as exceeding OTS's authority). Cf. In re Curtis, 83 B.R. 853 (Bankr. S.D. Ga. 1988) (Ga. Code Ann. § 57-101(6)(2) (1988 & Supp. 1993) prohibits prepayment penalties only in absence of contractual agreement for one; court validated express provision for prepayment penalty of 3 year's interest). But compare George v. Fowler, 978 P.2d 565 (Wash. App. 1999) (clause prohibiting prepayment is valid in absence of legislative ban on such clauses). (n50)Footnote 50. Note that even if the statute does not spell out the right to prepay, that right is implicit in any statute which requires a rebate upon prepayment. (n51)Footnote 51. The existence of a statute requiring rebates upon prepayment, in the absence of a statute compelling rebates upon default and acceleration, need not, however, be read as allowing the retention of unearned interest upon acceleration. See Glacier Lincoln-Mercury, Inc. v. Freeman, Consumer Cred. Guide (CCH) P 99,567 (Alaska Dist. Ct. 1970). (n52)Footnote 52. See Ch. 2 supra for an explanation of the Act's scope. The background of this legislation, and the issues arising under it, are discussed more fully in National Consumer Law Center, Truth in Lending Chapter 9 (6th ed. 2007). (n53)Footnote 53. 15 U.S.C. § 1639(c)(1). (n54)Footnote 54. A prepayment penalty, including use of the Rule of 78 to calculate rebates in loans with terms of 60 months or less (use of the Rule in all consumer credit transactions with terms 61 months is prohibited in any event), may be imposed where all elements of a five-prong exception are met as set out in 15 U.S.C. §§ 1639(c) (n55)Footnote 55. For a general discussion of federal preemption of mortgage loan limitations, see §§ 6.02[4] et seq. supra. Note, however, that federal preemption of usury ceilings on first mortgage loans under § 501 of DIDA does not preempt state limitations on prepayment charges. 12 C.F.R. § 590.3(c). See also S. Rep. No. 368, 96th Cong., 2d Sess. 19, reprinted in 1980 U.S.C.C.A.N. 236, 255. Further, state-chartered S&L's or other housing creditors may not invoke federal preemption under AMTPA to circumvent state restrictions on prepayment penalties. 12 C.F.R. §§ 560.34, 560.220 (1996). Non-depository lenders who regularly make loans or credit sales secured by residential realty or mobile homes may impose prepayment penalties in loans that fall under the Alternative Mortgage Parity Act. See 12 C.F.R. § 560.220 (allowing housing creditors to make alternative mortgage transactions, which under 12 C.F.R. § 560.34 may include prepay- Page 12 1-6 Debtor-Creditor Law § 6.03 ment penalties). See National Home Equity Mortg. Ass'n v. Face, 239 F.3d 633 (4th Cir. 2001) , cert. denied, 534 U.S. 823, 122 S. Ct. 58, 151 L. Ed. 2d 26 (2001) ; McCarthy v. Option One Mortg. Corp., 2001 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 22711 (N.D. Ill. Feb. 11, 2001) (non-federally chartered housing creditor can charge prepayment penalty, but only if it complies with OTS regulations); Shinn v. Encore Mortg. Servs., 96 F. Supp. 2d 419 (D.N.J. 2000) (housing creditor that complied with OTS regulations could charge prepayment penalty notwithstanding state law restrictions). (n56)Footnote 56. See 12 C.F.R. §§ 34.23, 34.24 (1996) (Regulations of the Comptroller of the Currency). (n57)Footnote 57. Prepayment penalties must be disclosed under 12 C.F.R. § 560.210 (1996). (n58)Footnote 58. 12 C.F.R. § 560.220 (allowing housing creditors to make alternative mortgage transactions, which under 12 C.F.R. § 560.34 may include prepayment penalties). See Nat'l Home Equity Mortg. Assn. v. Face, 239 F.3d 633 (4th Cir. 2001) . (n59)Footnote 59. 12 C.F.R. § 560.220 (as amended by 67 Fed. Reg. 60,542 (Sept. 26, 2002)) ; see Nat'l Home Equity Mortgage Ass'n v. Office of Thrift Supervision, 271 F. Supp. 2d 264 (D.D.C. 2003) (upholding amended regulation as within discretion of OTS). (n60)Footnote 60. 12 C.F.R. § 560.220 (allowing housing creditors to make alternative mortgage transactions, which under 12 C.F.R. § 560.34 may include prepayment penalties). See National Home Equity Mortgage Assn. v. Face, 239 F.3d 633 (4th Cir. 2001) ; McCarthy v. Option One Mortgage Corp., 2001 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 22711 (N.D. Ill. Feb. 11, 2001) (non-federally chartered housing creditor can charge prepayment penalty, but only if it complies with OTS regulations); Shinn v. Encore Mortgage Servs., 96 F. Supp. 2d 419 (D.N.J. 2000) (housing creditor that complied with OTS regulations could charge prepayment penalty notwithstanding state law restrictions). (n61)Footnote 61. See 12 C.F.R. § 701.21(c)(6) (1993). (n62)Footnote 62. See 24 C.F.R. §§ 201.17, 203.22(b) (1993). (n63)Footnote 63. 12 C.F.R. § 591.5. (n64)Footnote 63.1. Bednar v. Provident Bank, 937 A.2d 210 (Md. 2007) . (n65)Footnote 64. 15 U.S.C. § 1615. (n66)Footnote 65. See Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act, Ch. 2 supra . (n67)Footnote 66. 15 U.S.C. § 1639(c)(2)(D). (n68)Footnote 67. Home Ownership & Equity Protection Act, at § 151(e)(2)(C), amending 15 U.S.C. § 1610(b). (n69)Footnote 68. Singer, Sutherland Statutory Construction P 71.01 (5th ed.) See § 6.07[2] infra; see also National Consumer Law Center, Truth in Lending § 1.4.2.3 (5th ed. 2003).