Obvious Risks Policy and Claimant Inadvertence

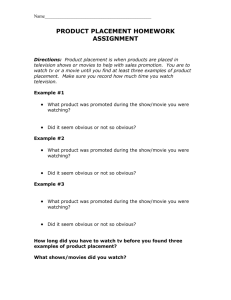

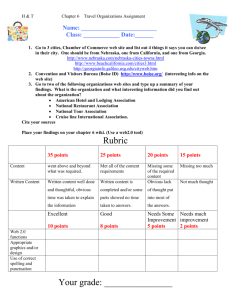

advertisement