Nelson Mandela

advertisement

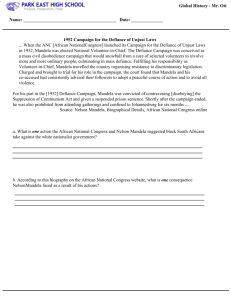

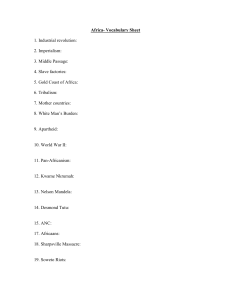

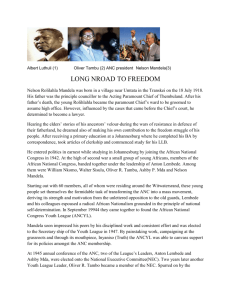

Anti-Apartheid Freedom Struggle – Events & Qualities (2.5) 9.5th Humanities 9 – Social Movements Nelson Mandela Reggie Finlayson Mayibuye Afrika: Let Africa Return By 1952 Nelson Mandela was president of the ANC Youth League, and he wanted a change in tactics. As Afrikaners celebrated their tricentennial, The ANC drafted a letter to Prime Ministers Malan, in it, they explained that they had exhausted all constitutional means of achieving rights for the black population. They demanded a repeal of the unjust laws that formed the basis of apartheid. If no action was taken, the organization would have to resort to extra-constitutional measure. Malan’s reply made it clear that this government had no intention of meeting the ANC’s demands. The prime minister stressed his desire to preserve white rule in South Africa and promised to use force if necessary to quell any black unrest. “We regarded Malan’s court dismissal of our demands as a declaration of war,” Mandela wrote in his autobiography. “We had no alternative but to resort to civil disobedience, and we embarked on preparations for mass action in earnest.” That was the start of the Defiance Campaign. One June 26, 1952, ANC leadership called for a national strike. Blacks, Indians, and colored marched through areas marked “White Only” and refused to carry passbooks that designated their racial status. Malan was as good as his word and met the strikers with mass arrests and police brutality. Mandela and others were arrested. But the strikers continued their efforts throughout the remainder of the year. The oppressed people of the country had awakened and did not plan another slumber. Walter Sisulu seemed to speak for many involved in the campaign when he made a statement upon his arrest. “As long as I enjoy the confidence of my people, and as long as there is a spark of life and energy in me, I shall fight with courage and determination for the abolition of discriminatory law and for the freedom of all South Africans” he said. He spent a week in jail rather than pay the finds that would have gotten him out immediately. The Defiance Campaign was largely nonviolent. In fact, international observers commented repeatedly on the peaceful nature of the protest. Yet confrontations sometimes did turn violent, often in response to police brutality. In New Brighton in October 1952, for instance, a white policeman shot two blacks who were suspected of theft. A crowd reacted angrily, and the policeman pumped more than twenty bullets into the charging mass before escaping. People continued their rampage, and before peace returned, seven blacks and four whites were dead. Another twenty-seven people were injured. The government used their example of the unrest as an excuse to clamp down even harder on the Defiance Campaign. In addition to arresting thousands of protesters, the government “banned” more than fifty strike leaders. Under South African law, a banned person was restricted from traveling, making public appearance, and speaking with other banned individuals, and participating in many other activities. By December 1952, arrests, bannings, and other government actions had halted the Defiance Campaign. Mandela, Sisulu and other were placed on trial. However, the courts refused to convict the men of the most serious charges of antigovernment activity. They were given nine-month suspended sentences. The movement gained ground. The ANC had succeeded in creating a united front against apartheid. It had focused world attention on the injustices in South Africa and had sprung into prominence. Membership increased greatly. Yet, while Mandela and other leaders celebrated these successes, the government in the capital city of Pretoria launched a defiance campaign of its own. Without a trial or formal charges, the government issued expanded banning orders against the bulk of the ANC leadership. It also declared that protesters could be whipped, jailed for up to three years, fined the equivalent of nearly $1,000, or be given any two of these penalties combined. Encouraging protest was punishable by an additional two years in prison for the equivalent of $500 in fines. These rulings forced the ANC to reconsider its strategy. Nearly 9,000 people had gone to jail during the campaign, and it remained nonviolent. The AND remained committed to peaceful demonstrations. It was the government that launched countless acts of violence against the people. In peaceful protest at a train station in 1960, a group of blacks refused to present their passbooks, or identification papers, to police. Sixty-nine people were killed and another 180 wounded when police opened fires. The incident was called the Sharpeville massacre. The world condemned the incident, as by now it had a number of other outrages by the South African government. The black community responded with more protests. In retaliation, the government declared a state of emergency, which allowed authorities to further suspend the rights of blacks and make even more arrests. Again, the crackdown had just the opposite effect of what was intended. With more of its leaders in jail, the ANC had a chance to plan new actions. The group selected Mandel to lead the ANC during the next phase of the struggle. The Black Pimpernel In 1961 the banning order ran out. Mandela had his public voice back, but he went underground to preserve it. With a frustrated police force frantic to keep an eye on him, Mandel began the live of fugitive. He traveled to the countryside. He met with rural activists and journalists to explain his positions and to argue his points. HE wrote letter to students, who were by then becoming a powerful force in the struggle. Mandela was invisible to the authorities, but he present was felt in nearly every part of the country. The police conducted a massive manhunt. But Mandela continued to escape them. Mandela’s courage and legend among the black people earned him the name, “the Black Pimpernel”. This was a label inspired by a literary hero who saves others from danger. Mandel sparked hope in a generation of black youth while at the same time upsetting the South African government. During this period, Mandela and a small group of ANC members formed a radical group called Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation). Previously the ANC had engaged in only nonviolent protests. But since peaceful protest had been met with police brutality and the loss of more and more rights, Spear of the Nation tried another tactic. The group decided to engage in acts of sabotage against property and the economy. These actions were designed to put pressure on the government to make changes. But the leaders were careful to plan acts that would not harm people. Just as the ANC moved towards limited acts of violence, the world praised its nearly fifty years of nonviolence. In December of 1961, the form ANC president, Albert Luthuli became the first African awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace. Within a week, Spear of the Nation bombed multiple sites. For example, ost offices and telephone booths were blown up, as were pass offices and electricity structures. After the bombings people began to listen to the problems of the black majority. But the government prepared for an internal war. Mandela explained that Spear of the Nation felt it had no course other than violence action. “All lawful modes of expressing opposition to [apartheid] had been closed during legislation, and we were placed in a position in which we had either to accept a permanent state of inferiority, or defy the government,” he said. By the mid-1970s, black students had stepped into the forefront of the struggle. Their work was similar to the student protests in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s. But unlike the US government, the South African government treated protesters like enemies of the state. Things came to a tragic end in 1976 when Afrikaans, the hated languages of the Bores, became a required course in South African schools. Students at all levels reacted by boycotting school. The largest boycott took place in Soweto township outside Johannesburg. Protests began peacefully, but the government took its usual stance of tolerating no defiance. The police moved in on the township. The events became known as the Soweto uprising. During sixteen months of the unrest, roughly 1,000 people died and 4,000 were injured. Most of the people killed or injured were children. Thousands of students were jailed. Some spent up to five year in prison, while others were never heard from again. The reign of terror continued the next year. So did the resistance. As soon as the authorities destroyed a leader, another would move to the front. The best-known student activist was Steven Biko. He was beaten to death in police custody. Other student leaders died mysteriously. All the while, the international community increased pressure on the government. Many countries stepped up economic boycotts of South Africa. They refused to invest in companies or buy products from South Africa. Since 1964, South African had been banned form the Olympics and other international competitions. It became apparent to the South African government that something had to be done. The only sane course was to release Nelson Mandela from prison and to open the political process to all South Africans. It would take the right leader to bring about change.