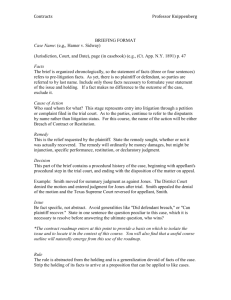

1985.010 - Supreme Court

advertisement

A10/1985 – Drew v Hobart Fire Brigade Full Court (Neasey J, Nettlefold J, Brettingham–Moore J) [Order Sheet] Serial No. 10/1985 List “A” File No. FCA 127/1985 ANTHONY BERNARD DREW v. HOBART FIRE BRIGADE REASONS FOR JUDGMENT FULL COURT: NEASEY J. NETTLEFOLD J. BRETTINGHAM–MOORE J. 15th March 1985 ORDERS OF THE COURT: 1. Appeal allowed. 2. Judgment given and entered after the trial of the action set aside and in lieu thereof, judgment for the appellant against the respondent for $85,000 damages. Full Court (Neasey J) [Page 1] Serial No. 10/1985 List “A” File No. FCA 127/1983 ANTHONY BERNARD DREW v. HOBART FIRE BRIGADE REASONS FOR JUDGMENT FULL COURT: NEASEY J. 15th March 1985 I agree with the reasons and conclusions of Brettingham–Moore J. and have nothing to add. Full Court (Nettlefold J) [Page 1] Serial No. 101985 List “A” File No. FCA 1271983 DREW v. THE HOBART FIRE BRIGADE BOARD REASONS FOR JUDGMENT FULL COURT: NETTLEFOLD J. 15th March 1985 The issue in this appeal is quite a narrow one. The only challenge to the judgment now pursued is to his Honour‘s conclusion that the facts did not establish a breach by the respondent of the duty of care which it owed to the appellant. At the trial of the action counsel agreed that it would be appropriate for the learned trial judge to apply the tests outlined by Mason J. in Wyong Shire Council v. Shirt (1979–80) 29 A.L.R. 217 at 221 in this passage:– “A risk of injury which is quite unlikely to occur, such as that which happened in Bolton v. Stone, may nevertheless be plainly foreseeable. Consequently, when we speak of a risk of injury as being ’foreseeable‘ we are not making any statement as to the probability or improbability of its occurrence, save that we are implicitly asserting that the risk is not one that is far–fetched or fanciful. Although it is true to say that in many cases the greater the degree of probability of the occurrence of the risk the more readily it will be perceived to be a risk, it certainly does not follow that a risk which is unlikely to occur is not foreseeable. In deciding whether there has been a breach of the duty of care the tribunal of fact must [Page 2] first ask itself whether a reasonable man in the defendant’s position would have foreseen that his conduct involved a risk of injury to the plaintiff or to a class of persons including the plaintiff. If the answer be in the affirmative, it is then for the tribunal of fact to determine what a reasonable man would do by way of response to the risk. The perception of the reasonable man‘s response calls for a consideration of the magnitude of the risk and the degree of the probability of its occurrence, along with the expense, difficulty and inconvenience of taking alleviating action and any other conflicting responsibilities which the defendant may have. It is only when these matters are balanced out that the tribunal of fact can confidently assert what is the standard of response to be ascribed to the reasonable man placed in the defendant’s position.” It is appropriate for us to apply that passage also. The dominant fact of the case is that the appellant suffered a life threatening injury while doing work he was employed to do in a manner not shown to have departed from the method accepted or acquiesced in by the respondent. I am satisfied that a reasonable man in the respondent‘s position would have foreseen that the method adopted for performing this recurring task involved a risk of injury to the employees called on to perform it. The medical evidence shows that an injury of the type suffered by the appellant could result from an application of force to an unprotected head of the order of severity of a punch. Other evidence, and in particular that of Mr. Johnston, shows that some application of force to the unprotected head of an employee was to be expected. And that evidence also shows that it was by no means unlikely that an event would occur in which such an application of force would be of the order of severity of a punch. I am satisfied that a reasonable man in the position of this respondent, in response to that risk, would have taken before the 19th August 1976 the steps which the respondent in fact took after the accident. Those steps could be taken [Page 3] easily and cheaply and they constituted a more efficient and much safer way of doing the work. If those steps had been taken before the 19th August 1976 this accident would not have occurred. I have given a great deal of thought to the question whether the approach which I have outlined has the effect of applying too high a standard of care. That is the real problem in the case, particularly in view of the opinion formed by the learned and experienced trial judge. But, after much thought, with respect, I consider that the learned judge gave too little weight to the following factors:– 1. The extremely vulnerable nature of the human head as shown by the medical evidence. 2. The confined space in which the work had to be done. 3. The fact that it was inevitable that from time to time a coupling on the end of a hanging hose would be in close proximity to the unprotected head of an employee who was concentrating on moving up and down to pull on the rope in order to raise the hoses to the top of the tower. It was to be expected that, when doing that work, an employee would be concentrating on his task and, hence, would not always be mindful of the proximity of the hanging couplings. It must not be overlooked that these couplings were heavy and there was a lug on the side of them. It was inevitable that, from time to time, there would be substantial movement of the hanging couplings. It is a trite piece of knowledge that a person is very vulnerable if he receives a blow to his unprotected head while his feet are firmly planted on the ground. It is that trite piece of knowledge which constitutes the principal reason why a responsible boxing manager will not let one of his charges fight if he is unfit; the risk of him being hit when his feet are flat on the ground so that he [Page 4] takes the unmitigated force of a powerful punch is far too great. As I have said, it was inevitable that, from time to time, the hanging couplings would be moving and, sometimes, moving to a considerable degree. There is a number of obvious reasons why movement would occur, not the least of which is force applied by hoses being raised to hoses already on pegs. Not infrequently movement would occur without an employee being conscious of it because he was concentrating on his task. An employee could get a solid blow to the head when the lug on a coupling came into his line of movement at a point above his head as he moved upwards to take fresh hold on the rope. While doing that his head could hit the coupling with considerable force while his feet were firmly planted on the ground. The probability is that this is precisely what happened to the appellant. I am aware of the fact that the learned judge rejected that view. But, with respect, I feel free to and I do differ from him on that point. The following is a significant passage in Pallier’s evidence, Pallier being a witness whom the learned judge accepted as truthful:– “As we were pulling up on the hoses, we‘d stand up grasp the rope and then you’d come down to a squatting position then stand up again to get afresh hold on the hose. During the standing up firefighter Drew grabbed his forehead and sat down and said he‘d hit his head.” Counsel for the respondent faintly argued that this Court should hold that, if the respondent was guilty of negligence, the appellant was guilty of contributory negligence. But the burden of proof of contributory negligence is on the respondent and that burden has not been discharged. The conduct of the appellant can be explained easily as understandable inadvertence not amounting to contributory negligence. [Page 5] For these reasons I am of the opinion that this Court should make the following orders:– 1. Appeal allowed. 2 . Judgment given and entered after the trial of the action set aside and in lieu thereof there is to be judgment for the appellant against the respondent for $85,000 damages. Full Court (Brettingham–Moore J) [Page 1] Serial No. 101985 List “A” File No. FCA 1271983 1855 of 1976 DREW v. THE HOBART FIRE BRIGADE BOARD REASONS FOR JUDGMENT FULL COURT: BRETTINGHAM–MOORE J. 15th March 1985 On or about 19th August 1976, the appellant was employed by the respondent. One of his duties was to hoist fire hoses to the top of a tower in order that they should dry. Whilst doing this, his head came into contact with a brass coupling on the end of a hose. This resulted in serious injuries. He brought an action against the respondent claiming damages for negligence and breach of duty and breach of contract of employment. The trial judge dismissed his claim, but assessed damages at the sum of $85,000. The appellant appealed from such decision on the following grounds:– “1. That the dismissal of the appellant’s claim was against the evidence and the weight of evidence and wrong in law. 2. That the learned trial judge erred in fact and in law in holding that a reasonable man in the position of an officer of the respondent would not have foreseen that the system of work involved a risk of injury to a class of persons including the plaintiff. [Page 2] 3. That the learned trial judge erred in fact in law in concluding that the magnitude of the risk of any injury and the degree of probability of its occurrence were not such as to call for any alleviating action. 4. That the findings referred to in grounds 2 and 3 hereof were against the evidence and the weight of evidence. 5. That the learned trial judge erred in assessing damages at $85,000 in that that sum was manifestly inadequate.” The Court was informed at the commencement of the hearing of this appeal that ground number 5 was abandoned. The relevant facts as found by his Honour the trial judge were not challenged. Those facts can conveniently be summarised as follow:– (1) The appellant and another employee were hoisting canvas hoses of a maximum length of 100 feet onto a tower to hang vertically to dry. This was done manually by means of a rope and pulley. (2) When fully hoisted, the centre of each hose was placed over a peg at a height of about 50 feet from the ground. (3) At each end of each hose was a brass coupling which weighed about 2¼ pounds. (4) The hoses were of variable lengths and therefore the brass couplings hung at variable heights from knee level to above head level of those standing on the ground. (5) These hose ends with the brass couplings were hanging in two rows about 1.2 metres apart at the base of the tower. [Page 3] (6) The men hoisting the hoses were required to work between these rows. (7) If the hoses were swinging or if they were obstructing those doing the hoisting they could be hung over the tower framework or could be tied back. (8) There was no wind at the time of the appellant‘s accident and they were not hung on the framework or tied back. (9) The ends of the hanging hoses were not “swinging” at the time of the accident although the ends of the hoses actually being hoisted were moving to a slight extent otherwise than in a vertical plane. (10) The appellant hit his head on a coupling when he stood up from a crouched position. (11) There had been no prior episode of injury from hose couplings but another employee, 6 feet 4 inches tall, had been hit by them on occasions around the shoulders and back when hoisting hoses. (12) The appellant said that he did not consider the hoses to be a danger during the process of hoisting them. It is clear that no protective headgear was worn prior to the accident by employees who were employed in hoisting the hoses but that such headgear was required to be worn subsequently. It is also clear that the hoses are now hoisted by means of an electric winch. His Honour’s comments as to the facts, his application of the law and his ultimate findings on the issue of liability are expressed in the following passage in his reasons for judgment:– [Page 4] “That the plaintiff suffered a blow to the head is undoubted. The difficulty is to determine the manner in which that blow occurred. I do not regard the plaintiff as a truthful witness. That fact has more importance in the context of damages than of liability, but it has some small significance in the latter context. Where there is a difference between his evidence and that of Pallier, I prefer the evidence of Pallier. But I can do no other than accept his evidence that he saw, or thought he saw, a coupling coming towards him; that he took evasive action, and that it was then that his head was struck. But I accept the evidence of Pallier that the plaintiff was not knocked down by the blow and he was crouched down heading outside the perimeter of the tower when Pallier saw him. Pallier said that the blow occurred as Drew was beginning to stand up from the crouched position. The conclusion seems inevitable that a hanging coupling and Drew‘s head made contact, but it seems to me, in the light of all the evidence, more probable than not that Drew moved towards the coupling rather than that the coupling swung towards him. The contact was not severe enough to knock him to the ground, but it was severe enough to have the medical consequences which have been detailed. The medical evidence was that in order to create those consequences the blow would have to be of the order of severity of a punch. But it is common knowledge that a blow of some severity can occur by a sharp movement of the head or body. Anyone who has struck his head on a cupboard door or in some other situation of reasonably close confinement can testify to the fact that it requires only a sharp movement of the head to cause a situation where some temporary loss of some part of consciousness can occur. Is the Board to be liable in damages to the plaintiff for an injury which occurred in these circumstances, and probably in this way? Both counsel were agreed that it would be appropriate for me to apply the tests outlined by Mason J. in Wyong Shire Council v. Shirt (1979–80) 29 A.L.R., 217 at 221, in this passage:– ’A risk of injury which is quite unlikely to occur, such as that which happened in Bolton v. Stone, may nevertheless be plainly foreseeable. Consequently, when we speak of a risk of injury as being ‘foreseeable’ we are not making any statement as to the probability or improbability of its occurrence, save that we are implicitly asserting that the risk is not one that is far–fetched or fanciful. Although it is true to say that in many cases the greater the degree of probability of the occurrence of the risk [Page 5] the more readily it will be perceived to be a risk, it certainly does not follow that a risk which is unlikely to occur is not foreseeable. In deciding whether there has been a breach of the duty of care the tribunal of fact must first ask itself whether a reasonable man in the defendant‘s position would have foreseen that his conduct involved a risk of injury to the plaintiff or to a class of persons including the plaintiff. If the answer be in the affirmative, it is then for the tribunal of fact to determine what a reasonable man would do by way of response to the risk. The perception of the reasonable man’s response calls for a consideration of the magnitude of the risk and the degree of the probability of its occurrence, along with the expense, difficulty and inconvenience of taking alleviating action and any other conflicting responsibilities which the defendant may have. It is only when these matters are balanced out that the tribunal of fact can confidently assert what is the standard of response to be ascribed to the reasonable man placed in the defendant‘s position.’ The first question to be asked then is whether reasonable men in the position of the officers of the Board would, or should have foreseen that the system used for raising the hoses to their drying positions was such as to involve a risk of injury to the plaintiff or a class of persons including the plaintiff. Injury in this context seems to me to mean much the same as the expression ‘bodily harm’ means in the criminal law, that is to say, a physiological change in the body which is more than trivial. Superintendent Johnson described having been ‘nudged’ in the course of carrying out this activity, but he did not depose to any injury having been sustained by a firefighter in the course of an activity which was carried out at very frequent intervals. It was not suggested that it had ever occurred to him that the process involved any risk of injury. The plaintiff himself said that he did not regard the system as dangerous. It was not suggested by Mr. Pallier that he saw any inherent danger in the process. It seems to me that there was nothing in the procedure used which would suggest to a reasonable person that it created any untoward risk of injury. Of course there is always risk of injury when a head is in proximity to a hard object, for example, the carrying out of work in confined spaces such as a boiler room, a yacht, a sawmill, a joinery room; wherever a person, by abruptly moving his head, may bring it into contact with a hard object [Page 6] there is some risk of injury, but it is not a duty of an employer to eliminate hard objects. I have come to the conclusion that a reasonable man in the position of an officer of the Board would not have foreseen that the system involved a risk of injury to a class of persons including the plaintiff. And even if such a reasonable man ought to have foreseen that there was some risk of injury, then, in my opinion, the magnitude of the risk and the degree of probability of its occurrence were not such as to call for any alleviating action. Accordingly, in my view, the plaintiff fails on the issue of liability.” Under s.47(2) of the Supreme Court Civil Procedure Act, a Full Court has full power to review the judgment appealed from on questions of fact as well as law. It is open to such Court to interfere with the decision of a trial judge because of failure to draw an inference which is open upon the evidence: Livingston v. Halvorsen (1978) 22 A.L.R. 213; Warren v. Coombes (1979) 142 C.L.R. 531; Sharma v. The Law Society of Tasmania, Unreported, Tas., Serial No. 221980, per Green C.J. I am unable to reach the same conclusion as the learned trial judge by applying the law to the facts and to the inferences to be drawn from the facts. I cannot agree with his Honour‘s view that there was nothing in the procedure used which would suggest to a reasonable person that it created any untoward risk of injury. It seems to me from the facts in this case that a risk of injury to persons such as the appellant when engaged in hoisting the hoses should have been foreseen. That risk was not, it seems to me, “far–fetched or fanciful”. There was a system whereby two men were pulling hoses up in a confined space with couplings hanging down, some at head height, quite close to them. Some of the hoses would move sideways for three or four inches from time to time. I consider that a reasonable person with knowledge of this system of work, as the respondent Board should have had, should have realised that there was a likelihood of injury [Page 7] to an employee placed in the same position as was the appellant at the relevant time. Such injury was not a matter of insignificance. Common experience indicates that, if the head comes into contact with a hard object such as one of these hose couplings, serious injury is possible. The evidence of Dr. Billings confirms this:– “HIS HONOUR: Well there is a question I want to ask, and it is probably appropriate to ask it now. Are you able to assist me at all, Doctor, in relation to the causation of the injury? I am a little puzzled that this subdural haemotoma could arise from an injury in which there was no apparent laceration or bruising of the skin of the scalp. WITNESS: Oh yes, that is absolutely consistent, Your Honour. In fact, it’s the rule, one could say, with subdural haemotomas that the injury can be relatively trivial, and what happens is that a little vessel which is running across the space between the dura and the brain is torn. And that can be in just a violent concussive movement the brain actually moves within the skull and tears the vessel. It‘s just a blow of that kind can cause that, even though it hasn’t been severe. HIS HONOUR: A slap you are illustrating, is that what you – WITNESS: Well, knocking the head, for instance, against a cupboard door is the kind of injury that I‘ve encountered on a number of occasions where a subdural haemotoma has resulted. HIS HONOUR: And just taking evasive action, could that do it? WITNESS: That would be very unlikely. That might occur in a very elderly person where the vessels, perhaps, were particularly fragile. But no normally it is a blow which is sufficient at any rate to cause movement of the brain within the cranial cavity.” The respondent could have adequately responded to the risk by requiring employees doing the work in question to wear protective helmets. The fact that these were required to be worn after the accident, and have in fact been worn, demonstrates that it was a practical step which [Page 8] could have been taken prior thereto. The provision of an electric winch subsequent to the accident also demonstrates another practical step which could have been taken beforehand. There is no evidence that either of these steps would have been impracticable or inconvenient or disproportionately expensive. There are accidents which occur in unusual circumstances and which are not due to any want of reasonable care on the part of the employer. But I do not regard this as being one of them. The presence of hoses hanging down with heavy couplings at their ends, near the heads of men working in a confined space, was something which in my view should have been regarded by the management as a potential cause of head injury unless protective steps were taken. The fact that the appellant did not consider the couplings to be a danger is not the end of the matter. The test is an objective one. It is a question whether a reasonable man in the position of the respondent Board ought to have foreseen the possibility of an employee hoisting the hoses sustaining an injury by hitting his head on a coupling. The dicta of Lord MacMillan in Glasgow Corporation v. Muir (1943) A.C. 448 at p.457 are apt:– “The standard of foresight of the reasonable man is, in one sense, an impersonal test. It eliminates the personal equation and is independent of the idiosyncrasies of the particular person whose conduct is in question. Some persons are by nature unduly timorous and imagine every path beset with lions. Others, of more robust temperament, fail to foresee or nonchalantly disregard even the most obvious dangers. The reasonable man is presumed to be free both from over–apprehension and from over– confidence, but there is a sense in which the standard of care of the reasonable man involves in its application a subjective element. It is still left to the judge to decide what, in the circumstances of the particular case, the reasonable man would have had in contemplation, and what, accordingly, the party sought to be made liable ought to have foreseen. Here there is room for diversity of [Page 9] view, as, indeed, is well illustrated in the present case. What to one judge may seem far–fetched may seem to another both natural and probable.” My own view is that no reasonable employer should have allowed its employees to work in the circumstances here without requiring them to wear protective headgear. The absence of accidents over a long period does not conclude the issue of foreseeability in favour of the respondent. It seems to me that this was due to good luck rather than good management. In my view the respondent was in breach of its duty to provide a safe system of work for the appellant. The question arises as to whether he was guilty of contributory negligence. In its amended defence the respondent alleged that the appellant was negligent in the following respects:– “(a) he did not keep a proper lookout whilst hoisting the hoses. (b) He placed himself in the vicinity of the hose couplings when he knew or ought to have known that they would swing and hit him. (c) He failed to cause the hose couplings to be restrained. (d) He hoisted the hoses without proper care causing the coupling attached to the hoses to swing about.” There is a relative dearth of evidence in relation to the issue of contributory negligence. I can find nothing to support the allegation contained in paragraph (d). As for (a), the trial judge’s finding that he accepted the appellant‘s evidence that he saw, or thought he saw, a coupling coming towards him and it was then that his head was struck does not support any inference that he was not keeping a proper look out. It seems to be open to find that [Page 10] the appellant was doing his best to keep an eye on the couplings in the course of hoisting the hoses in a confined space. As for (b), it does not seem to me that it was open to find that the appellant placed himself closer to the couplings than was necessary in the course of his duties, nor do I consider that it was open to find that he ought to have known that they would swing and hit him. That leaves paragraph (c) to be considered. I do not believe that it was open upon the evidence to say that the appellant was wanting in proper care in not restraining the hose couplings. There was no wind at the time. He was not the person in charge of the operation. If each hose had been secured to the side of the tower after it was fully hoisted, that would presumably have eliminated the danger. However, it seems to me that a direction to this effect was a matter for the management to decide upon and that the appellant cannot be blamed, under the circumstances, for not having taken the initiative. Since there is not now any challenge to his Honour’s assessment of damages, I would allow the appeal and direct that judgment be entered for the appellant (plaintiff) for $85,000.

![[J-56A&B-2014][MO – Eakin, J.] IN THE SUPREME COURT OF](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008438149_1-ddd67f54580e54c004e3a347786df2e1-300x300.png)