The Buddha: a lapsed Hindu

advertisement

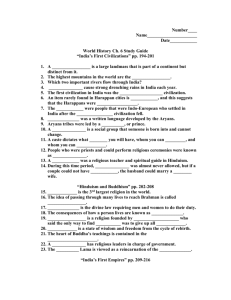

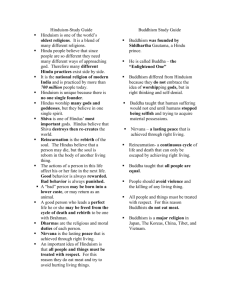

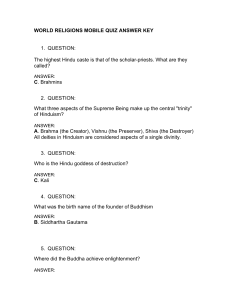

Lecture notes Week Three [This will not by any means be complete, but I wanted to supplement what your book text says, and what the two Power Point presentations convey with the following: ] It is vital to understand Buddhism by way of Hinduism. In other words, do not try to come directly to Guatama Buddha’s experiences and teaching from your occidental (Western) perspective and understand it as if he had “hatched these ideas” in Nebraska or London. Siddhartha was Indian; he was brought up in the classic Sanatana Dharma (what we call Hinduism now) and his understanding of the universe started there. As your Fisher text notes (p. 105), Siddartha tried to fulfill his religious destiny by following the paths of Hindu spiritual teachers; he led the life of a typical Indian sannyasin, fasting and denying himself physical pleasure, seeking to purify and liberate his soul from the endless wheel of karma by traditional religious means. When he pursued something, he pursued it doggedly. He eventually became, literally, skin and bones. The images of the Buddha that you see wherein he looks like the Scarecrow in the Wizard of Oz, as light as a feather and almost no flesh, stem from this period in his life. When he eventually despaired of coming to enlightenment , and stopped fasting and sat down in a restaurant and had a nice meal, his fellow disciples were aghast; horrified at his apparent indifference to “religious” solemnity. Guatama, it appeared, was not taking this religion business seriously. But he was. He just had lost faith in “religious” means to attain enlightenment and decided to live a more natural, balanced life of health instead of abstinence. In that renewed healthy state he sat down under a tree to re-commence the pursuit of enlightenment, much more comfortable, now that he had a bellyful. He reviewed his former lives and the cycle of existence on which he and other Hindus were dizzily whirling around. He saw his fellow Indians’ deeply religious (or, as he would say it: “superstitious”) affectations. He noted their multiple religious processes, elaborate rituals that kept them constantly thinking about the other world after death, and kept them seeking “help” from supposed spiritual beings or gods. He saw his community as addicted to religion, to the pantheon of deities and consorts of deities that we looked into briefly last week as we were introduced to the ancient Indian religion now called “Hinduism.” To Guatama it seemed futile and foolish to waste so much energy expressing extreme devotion to all of this, when, as he saw it, the existence of gods is even more illusory than our own existence – which is itself problematic. What he basically realized when he finally attained “enlightenment” is that his misery (one supposes: particularly his misery of recent years stemming from his fanatical religious excesses) and that of everyone derives from our mistakenly thinking we can find solutions to the problem of life in metaphysical (religious) exercises. We want and we do not have, so we suffer. We turn to religion to find solace from that suffering, but in doing so we cause ourselves MORE suffering, because we foster an illusion that help will be forthcoming from some heavenly being. Instead of nurturing and cultivating “religious consciousness,” as a Yoga master would urge us to do in order to become more “spiritual” and eventually attain moksha, that is, liberation from the karma-driven wheel of death and rebirth and existence, and unity with Brahman-consciousness, the Buddha says we should seek to rid ourselves of THAT desire, as well as all the other (less pure) desires. He too, like the Hindu culture of which he was a part, saw the problem as escaping the endless cycles of earthly existence. But to Buddha’s mind, trying to do so via devotion to illusory, non-existent deities was just a means to furthering one’s attachment to this samsara world. The goal, then, is to snuff out the desires that keep pulling us back into this cycle. The goal is to clear the mind of all chattering, both material and religious, that keep us focusing on our supposed “place in this world.” As long as we are striving to achieve any goal (even the goal of escaping samsara) we continue to foster the illusion that there is an individuated self who is thus striving. And as long as we perpetuate that false illusion we’ll never be free, for self-love (or flesh love) will continue to draw us back to this plane of existence, even after death. To a westerner, for whom existence is usually perceived as meaningful, and for whom, let’s face it: life is pretty comfortable, Buddha’s proposed “salvation” does not sound particularly inviting. But you have to put yourself in their (his contemporaries’) shoes and try to understand how bone-wearying and mind-numbingly miserable existence was. That one would want to escape the normal “daily life” would not have seemed odd there, then. Especially if one adds in the incredibly long eons of time that Hindu cosmology propounds, and imagines what a poor, dusty, disease-ridden denizen of a premodern society must have experienced life as, with nothing to look forward to except repeating this miserable dirty cycle again and again and again and again across millennia of millennia . . . If you’ve ever been really sick out in public – like, let’s say at a county fair, and someone keeps urging you to go on one whirling ride after another, and you’ve already got a splitting headache, and all you can think of is how much you’d like to find a cool dark place and just pass out from consciousness . . . . then maybe you can begin to relate to what Buddha was proposing. He was suggesting that if we could rid ourselves of concern with life, especially with ultimate concerns of life, we might have hope of eventually slipping into that cool dark oblivion in which there is no further consciousness of the wearying samsara, no further consciousness, in fact, of our own existence. To paraphrase Shakespeare’s Hamlet: “. . . or not to be. Ahh, to rest, perchance to sleep . . .” Bottom line: we need to understand Buddha first as an Indian; as a lapsed Hindu. As a thinker who renounced the entire religious superstructure that we glanced at last week under our study of Hinduism and said all that superstition (religion) hampers, rather than helps, our quest for nirvana, or non-consciousness. It should not surprise us, then, that Buddhism did not take hold in India. Instead, it flourished in China, in Thailand, in Burma, Tibet, Japan, Korea, Laos . . . cultures whose pantheons of deities were not developed so complexedly as that of the followers of Sanatana Dharma in the Indus valley and its neighboring subcontinent.