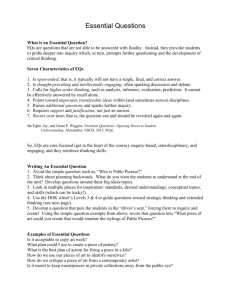

Appendix A: xxxxx thoughts on academic rigor, contributed post

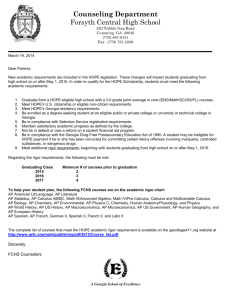

advertisement