Local Domestic Helpers in Hong Kong: A Vulnerable and

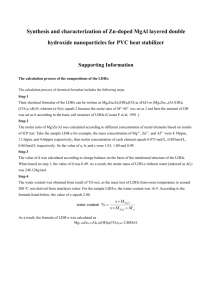

advertisement

Local Domestic Helpers in Hong Kong: A Vulnerable and Dispensable Lot? By Sally Chun in cooperation with the Hong Kong Domestic Workers General Union “I used to earn a lot working in garment factories before, and I felt good about myself. But now, I have to work as a domestic helper, being ordered around and yet earning so little. I feel really bad.” “I don’t have much choice [of jobs] because I haven’t studied much. I got married, then stayed home taking care of the kids, and now the children have grown up, but I don’t have that many job options any more.” The above comment expressed in a focus group discussion with six women domestic helpers stirred up a very strong reaction among them. While some domestic helpers do feel happy with their job, the ‘career path’ from an unpaid child-taker and home-maker to a low-paid domestic helper is typical of the working life of a certain section of the women workers in Hong Kong, the local part-time domestic helpers. To the amaze of many people, one out of ten families in Hong Kong hire domestic helpers cleaning up the house and/or taking care of their children/old people. According to a thematic household survey on "Views on employment of domestic helpers" in October-November 20001, out of the 2,105,800 households, 10.1% of them (212,500 households) employed domestic helpers, of which 87.9% hire foreign domestic helpers. The same survey showed that there were 214,100 domestic helpers, including 25,700 local domestic helpers (12.0%) and 188,400 foreign domestic helpers (88.0%). By law, all foreign domestic helpers 1 Thematic Household Survey Report No.5, Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong, August, 2001 were supposed to be working on full-time basis. And among the local counterparts, only 30.3% were working full-time. This brings us to the main issue in this study – the majority of local domestic helpers, invariably women, are working as part-timers whose entitlements to workers’ rights and benefits are called into question2. Full-time Foreign Domestic Helpers: A Policy Outcome in 1970s Every Sunday, foreign domestic helpers in Hong Kong have transformed the bustling central district in Hong Kong into a lively rest place on their day off. Many visitors to Hong Kong invariably have the same question in mind: “Do you really need so many domestic helpers?” This is a very good question – domestic helpers have always been a part of family life in Hong Kong in different mode. One local domestic helper interviewed recalls, back in the late 60s and early 70s, “It was very popular to work as a domestic helper in a western family…It was not easy to get the job. You had to be introduced by someone. A friend of my brother-in-law’s was working as a domestic helper in a western family at the Peak [area of the rich]. That family provided private tuition to my boss’s son. That friend introduced me to work for my boss, Chinese. That was my first job as a domestic helper, babysitting the kids…I was 17 or 18 at that time.” Layman memory of amahs is archived in pictures and movies in which local young girls in pony tail or single middle-aged women with hair tied up in a bun at the back worked in wealthy families. Unfortunately, at the time of writing, no statistics on the general profile of this kind of local domestic helper (commonly known as ‘amah’) is collated. What is clear though is that since mid-1970s, there was a shift to the hiring of foreign domestic helpers from Asian countries as a result of the government policy to ‘free’ the women population into the labor force in view of the growing economy. Instead of increasing child-care services and 2 Additional statistics obtained by email from the Census and Statistics Department, received March 2, 2004. Hong Kong statistics defines ‘part-time employment’ as employment fulfilling the following criteria: a) the number of usual days of work per week is less than 5 (for a person with a fixed number of working days per week); or b) the number of usual hours of work per working day is less than 6 (for a person with a fixed number of working days per week); or c) the number of usual hours of work per week is less than 30 (for a person without a fixed number of working days per week). facilities, the government opted for the importation of women workers from the poor provinces in Asia to take up the domestic work in local families. Against this background, the number of foreign domestic helpers has rocketed from roughly 8,000 in 1980 to 70,000 in 1990 and 213,891 by the end of July 2003. Among them, 60.67% came from the Philippines, 35.00% from Indonesia and 2.64% from Thailand3. Statistics in 2000 shows that in the main, foreign domestic helpers work in better off nuclear families with 3-4 family members and a household monthly income of $40,000 and above4. By late 1999, the tide took another turn when the Hong Kong government tried to combat the rising unemployment with the creation of part-time jobs. Part-time Local Domestic Helpers: A Policy Push in 2000s In October 2000, the Education and Manpower Bureau of the Hong Kong Government commissioned a consultancy firm to conduct a fact-finding survey on the domestic helpers market. The objective was to “create employment opportunities of local domestic helpers”, which in fact, was to reduce the unemployment rate among women workers5. 3 http://www.info.gov.hk/info/entry-dom.htm accessed March 11, 2004. Foreign domestic helpers are mostly live-in helpers. While foreign domestic helpers suffer various kinds of rights violations, this report will only study the problems confronting local domestic helpers in the context of informal workers. The plight of foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong is widely documented. For an overview, please visit Asian Migrant Centre at http://www.asian-migrants.org 4 5 Thematic Household Survey Report No.5, op. cit., page 60-61 In 2000, the government established a Task Force on Employment, comprised of the Financial Secretary, the Secretary for Works, the Secretary of Education and Manpower, the Secretary of Trade and Industry, and worker and employer representatives. It aimed to create 140,000 jobs in 2000-01, targeting women, single parents, youth, older workers and the disabled. (Source: Comments made by the ILO’s Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations in its 2000/71st Session on Employment Policy Convention, 1964 (No. 122) with reference to Hong Kong, http://webfusion.ilo.org/public/db/standards/normes/appl/index.cfm?lang=EN, accessed March 8, 2004) Economic Downturn and Unemployment after 1997 With no exception, Hong Kong was haunted by the specter of unemployment in face of slackened economic growth and corporate downsizing after the financial crisis in 1997. In the fourth quarter of 1997, real GDP growth decelerated markedly to 2.7% over a year earlier, following corresponding growth of 5.9%, 6.8% and 6.0% in the first three quarters of the year. For 1997 as a whole, real GDP grew by 5.3%. The economic downturn took its toll in1998 when the GDP contracted by 5.1% in real term. In1999, real GDP grew by 2.9% with the injection of government spending into the building and construction sector, and the economy picked up markedly in 2000 with a double-digit growth at 10.5%. However, in 2001, the economy dipped tremendously due to the economic downturn in the US and deepening slump in the world market, particularly after September 11. Real GDP recorded a marginal increase of 0.1%, and gradually picked up in 2002 and 2003 with a growth of 2.3% and 3.3% respectively. However, the problem of unemployment dragged on over the years from 1997 to 2003. It is noteworthy that underemployment6 increased in parallel to unemployment. The following table shows the corresponding GDP growth, unemployment and underemployment figures after the financial crisis in Asia: Year 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 Real GDP growth (%) +5.3 -5.1 +2.9 +10.5 +0.1 +2.3 +3.3 Unemployment Underemployment rate Rate (%) Rate (%) 2.2 4.7 6.2 4.9 5.1 7.3 7.9 Number (‘000) 71.2 154.1 207.5 166.9 174.8 255.5 277.6 1.1 2.5 2.9 2.8 2.5 3.0 3.5 Number (‘000) 37.1 81.8 96.9 93.5 85.5 105.2 123.5 (Source: Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong, various years) The ‘Underemployed’ is officially defined as employed persons who have involuntarily worked less than 35 hours per week but are available for additional work. 6 (Hidden) Unemployment of Women Workers: In the statistical landscape of unemployment, it is difficult to decode exactly how women workers are hit. Official statistics defines the unemployed as those persons aged 15 and over who are available for work but do not have a job. This definition excludes the ‘housewives,’ i.e. women who do not make themselves available for work. The statistical limitation is more complicated if we take into account whether the choice of staying home is ‘voluntary’ or not. An official survey in 2001-2002 reports that “some 88.8% of the female home-makers indicated that they decided to become a home-maker on their own accord and their mostly commonly cited reason for being a home-maker was ‘more time for taking care of household members’. The remaining 11.2% said that they became a home-maker based on the decision of other household members and their most commonly cited reason for their household members taking such a decision was ‘needed someone to handle the housework / take care of household members’.”7 The survey would have been more useful if the women were asked the following questions: “Will you prefer to work or become a home-maker if the government provides quality and easily accessible child-care services and facilities”; and “Will you prefer to work or become a home-maker if other family members share the housework?” Of course, this is just to lighten us up after going through the threatening figures and percentages. But the doubt is valid. Back in 1970s, women from other Asian countries started to take up much of the housework in Hong Kong, freeing the local women into the labor force and also freeing the government from increased expenses on child-care services and facilities. Those who cannot afford the foreign domestic helpers will have to ‘choose’ to stay home. In the same survey, it is reported that ‘too busy with housework’ was the most commonly cited reason for those female home-makers who indicated that they would not take up a paid job if being offered. Extracts from Thematic Household Survey Report No.14 on “Views on home-makers”, Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong, accessed online March 3, 2004 7 Less than one third of the female home-makers (a weird term to start with), however, did indicate that they would take up a paid job if being offered and the most common reason “to earn more money, more financially independent”. Put together, the lower female unemployment rate reflects the undercurrent of the traditional gender division of labor in household responsibilities, and the ‘decision’ of the women to stay home. The following table shows the unemployment rate by sex between 1997 and 2003: Year Male (%) Female (%) Overall (%) 1997 2.3 2.0 2.2 1998 5.2 4.0 4.7 1999 7.2 4.9 6.2 2000 5.6 4.1 4.9 2001 6.0 3.9 5.1 2002 8.4 6.0 7.3 2003 9.3 6.2 7.9 (Source: Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong, accessed online March 3, 2004) In a similar vein, some women workers may ‘choose’ to work less than 35 hours a week ‘voluntarily’ because they have to take care of household chores. This will suppress the number of underemployed women workers as well. The element of ‘voluntary choice’ is an interesting bridge explaining the difference in the number of employed persons working less than 35 hours a week and that statistically counted as underemployed as shown below: Year Underemployed Persons (‘000) Employed Employed Persons Working less than 35 Persons hours a week by sex Working less than 35 Number (‘000) Proportion of hours a week respective employed (‘000) persons (%) Male Female Male Female 1997 37.1 326.7 168.8 157.9 8.8 1998 81.8 321.3 174 147.3 9.4 1999 96.9 331.4 176.3 155.1 9.7 2000 93.5 323.3 171.2 152.1 9.2 2001 85.5 359.4 185.8 173.5 10.1 2002 105.2 368.8 184.6 184.2 10.3 2003 123.5 432.0 217.7 214.3 12.2 (Compiled from data by Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong, years) 12.6 11.6 12 11.2 12.3 12.9 14.9 various From the table above, it can be seen that while the proportion of men taking up jobs with shorter working hours increases over the years, signifying a growing trend of part-time employment, the ratio of women workers working shorter hours has always been higher than the male counterparts. This report will not go into the gender segmentation of the labor market. But the gender factors that brings women workers into part-time and casual employment, either ‘voluntarily’ or ‘involuntarily’, set the background for our study of the local domestic helpers in Hong Kong, numbering 25,700 by the end of 2000. Profile of the Local Domestic Helpers (LDHs) There is not much official statistics on the demographic profile of the LDHs. An official survey was conducted in October-November, 2000 to collect information from households on their preference of employing local and foreign domestic helpers. As mentioned earlier in this report, it was supposed to provide the statistical support to promote employment opportunities of LDHs in view of rising unemployment, with women as one of the target groups (please see footnote 5). As such, the findings are less on the LDHs themselves but the general employment environment from the perspective of the employers. The results were included in the paper prepared by the Legislative Council Panel on Manpower in October 2001. The major findings include: 1. 212,500 households, out of a total of 2.1 million, were hiring either a foreign domestic helper (about 185,700 FDHs)8 or a LDH (about 25,700 LDHs). Among the households employing domestic helpers, 87.9% were employing a FDH, giving a ratio of 7:1. 2. For those hiring LDHs, 34.7% cited ‘relative ease of communication with LDHs” as the primary reason for their choice. Other reasons included reliability (18.9%) and lower wages (18.4%) and more suitable working hours (14.2%). 3. 69.7% of the household employing LDHs did so on a part-time basis for a median of 12 hours per week. For the remaining 30.3% hiring full-time LDH, the majority (77.6%) did not stay overnight at the employer’s residence. 4. On the supply side, some 1.5% of the people interviewed indicated that they would take up job vacancies as LDHs. The majority is not prepared to work full time (69.8%). In another survey conducted by the Hong Kong Women Workers’ Association in 2001, there are more comprehensive figures on the LDHs themselves. Of the 50 LDHs interviewed, the following characteristics are reported: 8 The figure is slightly different from that provided in Thematic Household Survey Report No.5 which collates the statistics in question. The figure is quoted as it is. Age Mainly middle-aged women at the age of 30-39 (32%) and 40-49 (56%) Marital Status The majority was married Educational Level 46% has received primary education while 40% has studied up to Form 1-3 (corresponding to Grade 10-12). Length of employment in An overwhelming majority (72%) has worked less than present job one year in their present job Not working more than one year 82% due to household responsibilities Attended employee retraining 86% course Number of working hours per 22% worked for 18-39 hours while the majority (68%) week worked less than 18 hours a week. Wages On the average, the LDHs worked for 13.4 hours a week with an average monthly salary of $2005.2 or an hourly rate of $35 Wish to quit the job 66% have not thought about quitting the job mainly for the reason that it is easier to take care of the family in this job (66.6%) Job specification Mainly cleaning (84%) followed by ironing (54%). (Source: Survey on the Valuation of Low-Paid Jobs Taken Up by Women, Hong Kong Women Workers Association, October 2001) This profile coincides with the background information of the LDHs interviewed in this study (see Appendix). A distinctive feature in all these findings is that the LDHs take up the present job because it is easier for them to fulfill their domestic role i.e. they will not work full time. On top of this, middle-aged women with low education level and skills are actually left with little choice of employment, as pointed out by the LDHs in the focus group. Given the constraints of the domestic burden, age and educational background of this group of women, it doesn’t take much effort for the government to pin on domestic services as the ‘career path’ for them. The Manpower Panel paper mentioned above concluded that “while LDHs may not be able to compete with FDHs in the full time market, they would appeal to smaller households which do not have accommodation for a domestic helper and do not require full time domestic services”. [mainly general cleaning and tidying up the house] Since only 15,600 small households, out of a total of 504,900 in Hong Kong, were hiring domestic helpers, a conclusion was made that there was room to promote the employment of part-time LDHs. The government acted real fast. In 2002, the Employees’ Retraining Board (ERB) undertook a whole bunch of measures to implement the suggestion made by the Panel on Manpower. These included: 1. Pilot-run of a central job referral service, the Integrated Scheme for Local Domestic Helpers, in March 2002, comprising a Central Register of job vacancies and qualified retrainees, and the setting up of 13 servicing centres to offer referral services at district level. 2. Expand training capacity for LDHs (from 1700 in 1997-1998 to 12,000 in 2001-2002). 3. Pilot-run of a common assessment on DH courses. In late 2001, the ERB conducted skill assessment on its DH retrainees. Retrainees passing the evaluation would be issued a Competency Card. The ERB has also started planning for establishment of a Practical Skills Training and Assessment Centre tailored for common assessments of DHs. In 2001-2002, the number of retrainees in DH courses were 11,625, enrolled in 56 accredited training bodies (25.3% of total number of retrainees), and the placement rate was 82.2%. The Labor Department also runs an online job market for LDHs and other jobs (http://www.employment.labor.gov.hk/big5/domestic/jobseeker/seeker.asp), thus facilitating more direct and immediate job matching. In October 2003, the Panel on Manpower took one more step to boost the LDH market. It decided to relax the requirements to the Special Incentive Allowance Scheme which provides travelling allowances to qualified LDHs referred through the Integrated Scheme who have to travel across districts [following the administrative districts in HK) or work in “unsocial” hours i.e.6 pm to 9 am. The resources committed to the retraining of middle-aged women with little education and skill are phenomenal, and the ERB spares no effort to report the commendation of the UNESCR for its programme to help unskilled and unemployed workers in seeking employment9. While the government’s effort to combat unemployment is welcomed, its labor policy lags far behind the development of the growing size of irregular employment. The ERB puts it bluntly, the retraining programmes are designed from a market-driven approach. Decode – first and foremost, to satisfy the employers! 9 Annual Report 2001-2002, Employees Retraining Board, p.27 The LDHs, so employed, are strapped between either having no job or getting a harsh low-paid job that leaves them in pain and fatigue after work. Life as a Domestic Helper Given the time constraint, I have only talked with a focus group of six LDHs arranged by the Hong Kong Domestic Workers General Union (HKDWGU), an affiliate of the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions (HKCTU). All of them have taken the DH training course at the Retraining Centre at HKCTU, accredited by the Employees Retraining Board. In addition, in-depth interviews were conducted with the chairwoman and full-time organizer of the HKDWGU for further details and clarification, and their organising experience. Another in-depth interview was made with a staff member at the Hong Kong Women Workers Association, who has been involved in organising, without success, the LDHs in their district. It is aimed at collecting information to shed more light on the problems of organising. The focus group discussion is not meant to tap in-depth and comprehensive information about LDHs in Hong Kong. Instead, it is aimed to bring out the salient characteristics and concerns of the LDHs. Follow-up telephone interviews with the LDHs in the group were conducted to gather supplementary information. The LDHs are chosen on the criterion that they are not members of the HKDWGU. The choice is based on the consideration that they are least exposed to trade union education, and will thus more likely to respond as other LDHs. The following outlines the major problems as seen in the eye of the LDHs in the group. The legal and policy context that put the LDHs in a disadvantaged position is also discussed. Low Wages and Devaluation of Domestic Work On the average, LDHs fetch $35-$50 an hour, depending on the number of hours and days required. Usually, the rate is higher if they are only asked to go once a week and vice versa. Take the example of one LDH in the focus group. She is earning $1200 a week, working 5 hours a day, 34 hours a week. By the end of the month, she can get $4800 only, far below the median monthly earnings of $10,00010 in Hong Kong. 10 Figure obtained by telephone inquiry with the Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong, March 12, 2004. Another LDH gets even less. She has to work 3 hours a day and 6 days a week, and earns only $3000 a month! Others who are not that ‘lucky’ to get a regular DH job has to eke out their living by taking up more than one job. One LDH in the focus group has to work for three families in a week, 2-3 hours a day and once a week for $50-60 an hour. Assuming that she has two 3-hour jobs at $50 and one 2-hour job at $60, her weekly earnings will be $420. This means she earns $1680 a month only! To earn more, she also takes up casual one-off jobs that bring her some extra bucks. If she ever has to earn somewhere near $4000, she has to work for at least 6 families a week. THIS IS WHAT SHE IS DOING RIGHT NOW. For a government that only looks at figures, it is not surprisingly to have such a comment: “The Scheme [Integrated Scheme for LDHs] not only refers suitable candidates to employers, but also facilitates retrainees to obtain several part-time jobs [my own emphasis] to fit their schedules and needs. The Scheme is therefor a win-win solution for both the employers… and the retrainees… It is expected that in full operation, the Scheme would attract 2,000 to 3,000 LDH vacancies a month.” (Annual Report 2001-2002, Employees Retraining Board, Hong Kong) This says it all – the government is just trying to reduce the unemployment rate by exploiting the personal situation of middle-aged low-skilled women workers without paying heed to the quality of employment. The LDHs need to take several part-time jobs because the pay is shamelessly low and there is no minimum wage standard in Hong Kong. It must be noted that at the operational level, the ERB contributes directly to the low wages. The present requirement for an accredited training body to run a certain course is to achieve 70% placement rate. Otherwise, the course may be cut. The negative consequence is obvious. Instead of trying to maintain a reasonable level of wages for the LDHs, there is the tendency for the selected referral service centres to push the LDHs out to the market despite the low wages. However, it is astonishing that most of the LDHs interviewed (78%) in the survey by HKWWA are satisfied with their pay. It is doubtful whether they really mean it or whether they respond out of the mindset of ‘lesser evil’, i.e. better than nothing. The LDHs in the focus group do complain about the low wages, but then they generally say, “It’s very difficult. I have no choice. With my background and age, it’s difficult for me to get a job.” Furthermore, they generally see domestic service as dispensable and feel that they have very little bargaining power because “the job is dispensable”, and the employers can do without it. Work Intensity, Hidden Health Hazards and Dysfunctional Legal Protection Imagine cleaning up dishes piled up for one week, cleaning the kitchen, the floor and the window, and then ironing the clothes stacked for one week, all in three hours. This is a typical working session for the LDHs. If they are experienced, they will know how to do it in such a way that the tasks can be completed within the time slot. But very often, they have to work longer. Some get extra pay while others don’t, depending a lot on the employers because most of them feel “too embarrassed” to ask for it. The pay is of lesser concern to the LDHs I talked with because either they get paid extra or they don’t work that much longer. The impact of work intensity on their health is more of a concern. They say: “I feel very tired every time after the cleaning because it is very intensive. I have to finish the cleaning within a few hours, and it is really straining the muscle and very exhausting.” The hidden occupational health hazard is more serious than fatigue – the risk of developing tenosynovitis11 (locally dubbed ‘tennis-ball elbow’). The intensive repetitive movement in cleaning work poses potential danger to the LDHs, particularly because most of them work for a few hours, and thus have to work real fast to complete the tasks. Statistics from the Occupational Health and Safety Council indicates continuous increases of cases of tenosynovitis of Hand or Forearm: 1993 2 1994 1 1995 32 1996 54 1997 54 1998 71 1999 54 2000 81 2001 90 2002 35 However, there is no detailed breakdown by profession of the confirmed cases. It was reported that out of the 35 cases in 2002, 20 of them are in the “community, 11 Tenosynovitis is the tender swelling of the tendons, which connect muscles to the bones. It causes pain, tenderness, and swelling of the affected area, and also stiffness of the joint which is moved by the tendon. It may just last a few days, but in some cases can go on for many weeks or even months. Usually, however, treatment can help. Probably the most common recognisable cause is overuse through heavy and/or repetitive physical activity. It can affect any tendon in the body but is possibly most commonly seen in the wrist and hand. (Source: Medinfo at http://www.medinfo.co.uk/conditions/tenosynovitis.html, accesses March 12, 2004) social and personal services”12. Two domestic helpers were confirmed to have tenosynovitis in 1998 and 1999, representing a minimal proportion of the total number cases.13. The LDHs in the focus group do not mention that they have this problem. However, another interviewee, Ah Bo, Chairwoman of the Hong Kong Domestic Workers General Union, who has worked as a LDH for a decade, has this to say: “I don’t want to be a DH. It’s monotonous, and I have problems with my arm [tennis-ball elbow] because of the cleaning work. It hurts terribly in winter.” Under the Employees Compensation Ordinance in Hong Kong, which governs matters related to occupational health and safety, three common kinds of hand and arm problems inflicting domestic helpers are confirmed as occupational diseases14. As such, LDHs are entitled to get compensation if they have developed occupational diseases during the prescribed period (one year as laid down in the Ordinance). Another hazard in domestic service is back injury from falling. The LDHs in the group have not been injured but they express that this is a serious concern. Climbing up and down to clean the window or light bulb is common part of the domestic work. They have their own way to prevent accidents like this by refusing to do dangerous tasks. When asked what they will do if they are injured, they say that they will “take care of the problem by themselves”. This brings out one of the most serious problems confronting the LDHs – no insurance coverage for accidents and diseases. The major legal and policy defects are: 1. Legal constraint and Conflicts with Government Measures a. Casual vs. Part-time Employment 12 Statistics on Confirmed Occupational Diseases by Industry in 2002, Occupational Safety and Health Council, http://www.oshc.org.hk/eng/documents/statistics2/2002/OD-1e.html, accessed March 12, 2004. 13 In 1998 and 1999, there were 71 and 55 confirmed cases of tenosynovitis. (Source: Supplementary Information on Occupational Injuries to Hands and Arms sought by the Legislative Council Manpower Panel at its meeting on 15 Feb 2001, LC Paper No. CB(2)1145/00-01 (01)) 14 Item A7 -- Bursitis or subcutaneous cellulitis arising at or about the elbow due to severe or prolonged external friction or pressure at or about the elbow (Beat elbow); Item A8 – traumatic inflammation of the tendons of the hand or forearm (including elbow), or of the associated tendon sheaths due to manual labor or frequent or repeated movements of the hand or wrist; and Item A9 – carpal tunnel syndrome caused by repetitive use of hand-held powered tools whose internal parts vibrate so as to transmit that vibration to the hand. Some LDHs are excluded legal protection. Chapter 1 of the Employees Compensation Ordinance stipulates that casual employees are not covered, but the law is still applicable to part-time DHs. The Ordinance does not offer a definition of ‘casual’ employees. If it takes on the definition used for statistical purposes in Hong Kong15, LDHs working in one-off or short-term temporary jobs16 will be affected. The one-off job is of particular relevance to the LDHs who join the Chinese New Year Cleaning Scheme coordinated by the Employees Retraining Board. This is also a big annual event for the Domestic Workers General Union, which arranges some 300 LDHs to do the one-day cleaning job. However, the employers generally think that it stands less chance to have accidents in just one day. But in any event, the status of employment can be considered as casual, and leave the LDHs without legal protection. b. Employees vs Self-employed Another legal ambiguity is whether the LDHs are seen as self-employed or employees, particularly in one-off cleaning jobs like the Chinese New Year Cleaning. According to the law, self-employed persons have to take out their own insurance policy. Ultimately, it is up to the court to rule on the status of employment. The court will look at certain basic things like whether the employer provides the cleaning tools and agents, whether there are fixed working hours, whether the DH has to get the approval to take leave or to resign, whether the employer hires somebody to assist the DH, etc. The HKDWGU has not come across such cases yet, and they do not know what chances the LDHs stand. This is a ridiculous inconsistency on the part of the ERB. While it lauds the annual scheme in creating jobs for the LDHs, it is actually overtly pushing them into a legal vacuum, which saves the insurance expenses of the employers, but exposing the LDHs to potential physical and financial losses. However, the ERB does get worried that something serious will happen some day. This gives the leeway to work out something within the structure and policy of the ERB. 2. Enforcement Problem Under the same Ordinance, all employers are required to take out insurance policy for the LDHs regardless of the number of hours they work (except for the casual employees mentioned above). However, many of them fail to do so. The LDHs in the group do recall that some employers have asked for the personal information, which is supposed to be for purchasing policies. But they have no idea whether the employers really do so. And usually, they will not request the employers to take out policies for them, fearing that they will lose the job. At Casual employees’ are defined as those who are employed on a day-to-day basis or for a fixed period of less than 60 days. 15 16 There are two common temporary LDH jobs in Hong Kong: 1) when the foreign domestic helpers are off for holidays and 2) the month after child birth. times of injuries, the LDHs mostly will not pursue anything knowing that they cannot get anything. Ah Bo, Chairwoman of the Domestic Workers General Union, explains that more and more employers take out insurance policies especially after a DH fell from the 26th floor and died. Another problem is the apportioning of responsibilities in the case of occupational diseases. As outlined above, LDHs often work for more than one employer. When it comes to compensation, it is difficult to ascertain who should be bear the responsibility. Actually, the Employees Compensation Ordinance does address this situation. Chapter 2 of the Ordinance stipulates that “if the employee has been employed by more than one employer during the prescribed period in the same or in a similar occupation, all the employers may be responsible for paying compensation, though not necessarily to the same extent”. However, the Ordinance does not lay down how the legal provision is to be enforced in contrast to the detailed clauses on compensation for work-related injuries. 3. Inadequate Promotion of Remedial Services Occupation therapy and similar treatment can help with tenosynovitis of the hands and arms. There are currently two occupational health clinics operated by the Labor Department. However, Yu, organizer at the HKDWGU, comments that very few LDHs know about the clinics. Secondly, since they are not covered by insurance policies, the LDHs have to pay out of their own pocket, and there are no provisions of subsidies from any government department. Many LDHs do it their own way, taking painkiller or consulting Chinese doctors. In the worst scenario, when the pain is unbearable, the LDHs will simply quit the job without getting any cent from the employer, but bringing a painful body home. 17 There are isolated cases of accident claims made by the LDHs: The LDH fell and the shoulder joint was dislocated from a fall while cleaning the cupboard. She was sent to the hospital. She earned about $10,000 from various jobs like cleaning and street vending. She had to stop working for more than a year. Luckily, her employer is the boss of a company and the house is registered as the office. And so, she was covered under the company’s insurance policy as the company’s employee. The LDH was very independent and took care of the case by herself. The LDH cut her hand when she picked up the rubbish. The case was brought to the labor department for mediation, and the employer paid the compensation. Again, she took care of the case by herself. 17 The current fee is $100 for the first consultation, and $60 for each follow-up consultation. This and other information in this paragraph is obtained from the interview with the organizer at HKDWGU, February 2004. In the Chinese New Year Cleaning Scheme last year, the LDH fell from a height. She didn’t plan to seek compensation. But CTU’s Job Training Centre has taken out third party insurance policy and paid for some of the medical expenses. But actually, if they didn’t take the step to contact her, she would just leave it. Exclusion of DHs from Pensions Scheme All the LDHs in the focus group pinpoint pensions as the first thing to fight for. The reason cited is closely tied with their life pattern – they do not have much savings because they have not worked for quite some time when had to took care of the kids. And now they do not earn much as a DH. They are really worried about their livelihood when they get old. Ironically, while the LDHs as a disadvantaged group should be better protected, they are excluded from the mandatory contributory pension scheme, the Mandatory Provident Fund Scheme. Actually, the exclusion is applied to all domestic helpers, foreign and local. It is believed that originally it targeted foreign domestic helpers, but to avoid the accusation of racial discrimination, the government slashed the whole category altogether. As such, regardless of their status of employment and monthly earnings, LDHs do not enjoy any retirement protection. This is obviously another kind of discrimination. The 4.18 Rule and Exclusion from basic workers’ rights The LDHs in the focus group knows very little about the “4.18 Rule’, which is actually one of the major issues in the eye of the Hong Kong Domestic Workers General Union, and other workers’ groups in general. The 4.18 Rule is a local term to describe the legal definition of “continuous employment” that demarcates which categories of workers are fully protected. According to the First Schedule of the Employment Ordinance, “where at any time an employee has been employed under a contract of employment during the period of 4 or more weeks next preceding such time he shall be deemed to have been in continuous employment during that period” and “no week shall count unless the employee has worked for 18 hours or more in that week”. A survey in 2001 shows that there were some 128, 700 employees in the nongovernment sector working for less than 4 weeks continuously for their employers and/or less than 18 hours per week, representing 5% of the 2,592,200 employees in the non-government sector. Among these non-4.18 workers, 28,900 of them worked less than 18 hours irrespective of the length of service. The remaining 99,800 workers worked for 18 or more hours a week but for less than 4 weeks18. In practice, non-4.18 workers can either be casual or part-time workers. This complicates the issue of legal protection because, as in the case of occupational health and safety, casual workers are not covered while part-time workers are. For the purpose in this section, non-4.18 workers are seen only in terms of the hours of work. The very exercise to conduct a survey specifically on the non-4.18 workers, obviously in response to the pressure from the trade unions and workers’ groups to change the law, reflects the pressing nature of the issue. There are a certain sector of the workers, now termed as marginalised workers who are usually middle-aged workers in low-paid jobs (and predominantly women)19, do not enjoy the basic rights and benefits because they do not work for 18 hours a week. The finger specifically points to the dirty practices of employers who try to fix the terms of employment in such a way that the workers cannot work for 18 hours, and thus avoiding the expenses on various benefits laid down in the Employment Ordinance. As it stands, non-4.18 workers are only entitled to wage protection, protection against anti-union discrimination, granting of statutory holidays, protection against unreasonable and unlawful dismissal under the Employment Ordinance20, and are protected by the Employees’ compensation Ordinance and Mandatory Provident Fund Schemes Ordinance. This means that they’d better don’t get sick, pregnant, holidays and just work for whatever wages are offered to them! For LDHs, they have nothing when they retire. And if they happen to be casual workers, they have to take care of themselves if they are injured or develop “tennis-ball” elbows. Obviously, the 4.18 Rule is a top concern for the LDHs given the short working hours they normally work for. The ridiculous thing is that, when a LDH has to work long hours a week for different employers in order to maintain the earnings, she is still a non-4.18 employee with any one of the employers, and is therefore not fully protected by the Employment Ordinance. This is unfair and unreasonable. And one LDH in the focus group recounts that with one employer, she is asked to work for 3.5 hours a day, 5 days a week. How many hours is it in a week? 17.5 hours a week! With just a small click on the calculator by the employer, the LDH is stripped of a whole bunch of benefits. 18 Social date collected via the General Household Survey: Special Topics Report No. 32, Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong, 2001, soft copy downloaded March 10, 2004. 19 Non-4.18 workers are mostly in their late 30s (median age of 39) earning a median wage of $330 a day. The proportions of men and women are 58.1% and 41.9% respectively. The pattern is very different if we just look at those who work for less than 18 hours a week. In this category, the median age is 42, and the majority (73.4%) is women working on an hourly rate (42.4%) in ‘community, social and personal services’, earning a median wage of $200 a day. (Source: Social date collected via the General Household Survey: Special Topics Report No. 32, ibid.) 20 Full rights and benefits guaranteed under the Employment Ordinance include paid statutory holidays, paid annual leave, sickness allowance, maternity leave and pay, notification of termination of employment, etc. Organising and Advocacy From the interviews, three major issues have been identified: The 4.18 Rule related to the full rights and benefits of the LDHs under the Employment Ordinance; The legal constraints and enforcement problems related to the compensation for work-related injuries and diseases; and The absence of pensions scheme for LDHs. In the following sections, I will outline these initiatives and their outcome and highlight the possible points of departure for advocacy. 1. Abolishing the 4.18 Rule Actually, back in 2000-2001, there were coordinated efforts calling for legal and policy changes with specific reference to the 4.18 Rule21. The Hong Kong Domestic Workers General Union, formed in July 2001, acted on this issue right away, calling for the abolition of the 4.18 Rule to the effect that all workers, regardless of their status of employment, are fully protected by the Employment Ordinance. The HKDWGU is particularly concerned with gender discrimination implicit in the 4.18 Rule because many women workers are forced to work less than 18 hours due to the domestic burden22. The Hong Kong Women Workers Association and the Hong Kong Women Centre who also organized the LDHs joined the campaign as well. The problem has attracted much press coverage, citing employers’ practices in various sectors, which exploit the 4.18 Rule to avoid their legal obligations. With a legislature dominated by pro-government and business interests, the voices fall on deaf ears. The harvest is not good but there are still some fruits at different levels: The Census and Statistics Department was asked to conduct a survey on the profile and benefits of non-4.18 employers under the Employment Ordinance in the non-government sector. The findings were compiled into “Special Topics Report No. 32” cited above; In its paper written on January 18, 2001, the Labor Advisory Board made a recommendation to amend the Employment Ordinance so that all the workers are fully protected. The paper pointed out that the Hong Kong economy and labor In 2000, under the banner of “Marginal Workers Living Agenda”, Oxfam Hong Kong initiated a series of actions pushing for wider debate and policy changes on the problems related to irregular employment. The 4.18 Rule was a major issue in the advocacy campaign. A loose coalition comprising trade unions and workers’ groups was formed. Due to complexity of the issue and resilience of the government against granting more workers’ rights, nothing concrete came up. The campaign petered out with the staff changes at Oxfam Hong Kong. 21 22 Refer to Footnote 19 for the related statistics. The position of the union is outlined in the press statement of HKDWGU issued on October 14, 2001. force had undergone great changes over the decade and it’s time to review whether the 4.18 Rule was still appropriate. It further stressed that the Ordinance should be brought in line with the Mandatory Provident Fund Schemes Ordinance and Employees Compensation Ordinance, which did not limit the hours of work. The paper also highlighted the fact that more and more employers would exploit the 4.18 Rule to cut the employees’ benefits. This is a promising step. However, the recommendation has stayed as it is – a recommendation In the ultimate place, the Legislative Council, three labor councilors raised respective motions in 2000, 2001 and 200223: Chan Yuen Han from the Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions (FTU) urged the government to abolish the 4.18 Rule on October 18, 2000; Leung Fu Wah from FTU urged the government to relax the definition of "continuous contract" in the Employment Ordinance to reasonably cover all paid employees, including part-time employees on April 25, 2001. Lee Cheuk Yan from the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions (CTU) raised an amendment motion to Leung’s on April 25, 2001, urging for the abolition of the restriction on the hours of work in the Employment Ordinance, making reference to the ILO Convention No. 175 regarding the protection of part-time workers. Leung Fu Wah from FTU raised a water-downed motion on April 24, 2002, urging the government to “adopt active measures to ensure that employees enjoy reasonable and legitimate labor protection”, making no specific reference to the issue of 4.18. The advocacy campaign gradually petered out, and nothing concrete has moved so far. Back then, the alternative of legislating on a Part-time Law was raised. The general orientation at that time was towards an amendment of the existing laws, and the Part-time Law was put on the back burner. It should be noted that the Hong Kong government has not ratified the ILO Convention No. 175 on Part-time Work, and there is not much discussion on legal changes regarding part-time laws. This is probably due to the fact that discussion on the protection of irregular workers is overwhelmed by the main demand of abolishing the 4.18 Rule. A serious analysis of part-time work and relevant law is thus essential in bringing out alternatives for future action. In terms of policy, the study on parttime laws is highly relevant in view of the increasing number of part-time workers in Hong Kong, who are mostly middle-aged women workers (59.4%). Survey Period 23 Number of Part-time As % of Total Employees at Median Age Motion debates in the current setup of the Legislative Council are merely gestures with no teeth at all. But the motion debates quoted are important in a sense that the two trade union federations from the two poles of the trade union world in Hong Kong stand on the same side. In any event, it is not surprising that all the motions are defeated. Oct-Dec 1997 Jan-Feb 1999 July-Sept 2000 April-June 2002 Employees the Time of Survey 82 000 116 200 122 000 130 900 2.8 4.1 4.3 4.7 40 40 43 42 (Source: Special Topics Report No.33, Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong) 2. Instituting a central OSH compensation fund One of the missions of the HKDWGU is to “set up a centralised compensation scheme of work-related injuries and illness”. This is a logical policy recommendation in view of the problems discussed in previous paragraphs. In fact, a local industrial victims’ rights group, the Association for the Rights of Industrial Accident Victims (ARIAV), has also been fighting for such a fund. In its paper presented to the Legislative Council Panel on Manpower on January 18, 2001, ARIAV explained that the centralised system “seeks to transfer the duties currently undertaken by different private insurance companies, such as the underwriting of labor insurance, management of insurance levies and payment of compensation, to a centralised fund”. Business is business. Leaving the task of compensation to the private insurance industry is actually putting the injured workers to the axe of the insurers. The HKDWGU is also very clear on this stance, that it should be the responsibility of the government to ensure that the health and safety of the workers is well protected, and fairly compensated in case of injuries and diseases. HKDWGU organizer, Yu, recalls that when they approached the Labor Department on this issue, it offers a funny counter-suggestion – it asks the LDHs to set up an insurance company collectively and take care of the problem by themselves. As a matter, according to Yu, many employers are willing to pay a small sum of money to protect themselves. The point is that the government has not set up a mechanism to coordinate the whole thing. The current situation is that the employers have to take out individual insurance policies, and they may not want to spend the money. With a centralised system, the premium can also be shared among the employers, and all the LDHs are entitled to compensation benefits regardless of how many employers they work for. Although they haven’t come up with a detailed recommendation on the set up of the fund, the idea is seemingly the only solution way out in the current employment situation of the LDHs. Right now, there is a centralised compensation system catering to workers suffering from work-related hearing impairment. With this precedent, the idea in itself will not be new to the government and stands a better chance of being accepted. The remaining question is that who should administer the fund. One possible body is the Employees Retraining Board and its network of job referral service centres. For one obvious reason, the ERB and its network is the largest recruitment agency for LDHs, and the centres are in constant contact with the employers and LDHs. This means that some kind of institutional prototype is already in place. Secondly, as a matter of principle, the ERB should bear the responsibility of providing quality employment to the unemployed, but not just any jobs that help them boost the placement rate. However, there is not much concerted effort among the trade unions and workers’ groups to sustain the fight for the scheme. On top of it, the legal constraint that casual workers are not covered by the Employees Compensation Ordinance is seldom mentioned. Fresh inputs in this direction worth trying in order to raise the issue and the associated demand for a centralised compensation system. 3. Calling for a universal pension scheme Many trade unions and workers’ groups, including the HKDWGU, have been calling for a universal pension scheme that offers retirement protection to the whole population. As with other issues, the call has died down over the years. For the HKDWGU, even though the LDHs express grave concern about their life when they get old, and that they are excluded even from the not-satisfactory pension scheme, there are scanty actions working on the issue. Conclusion: Problems in Organising At this point, my friend suggested to me that I should make the conclusion short by saying “CHANGE EVERYTHING”. I suggested saying “NOT MUCH CAN BE CHANGED YET”. This is not an appropriate way to write a research report. But I am not an armchair researcher. Looking at the rough hands and beat elbows and tired bodies of the LDHs (I have tried to call one LDH late at night around 10pm. She was not still working. I called the next morning around 9am. She was also working), it is not appropriate to simply say that this and that should be changed. Putting the three major demands together, no one will say that the fight is easy. On top of that, in the case of the HKDWGU, it is pre-occupied by organizational consolidation and securing job placements for the LDHs. It is a hard fact that without a job, with the HKDWGU not addressing their employment concerns, the LDHs will just stay away from the union and organising. Chairwoman of the HKDWGU has put the fight for better travelling allowance as the No.1 task ahead. This is a practical concern for the LDHs. Their hard-earned income will otherwise be eaten up by the travelling expenses if they have to work far away from home. And we have to remember that they may have to travel across the city for more than one employer. Finally, the dispersed employment and job insecurity of domestic work makes it extremely difficult to organize. The HKDWGU fares better since they can gather the LDHs through the job training classes sponsored by the ERB. This means that the retrainees can get allowances and will enroll in the courses at their retraining centre. The physical space creates the space for organising whereby the organizers will chip in trade union education in between sessions and at break. This is how the HKDWGU was formed. The failure of the Hong Kong Women Workers Association in organising the LDHs is a vivid counter point. They refuse to take the money from the ERB because this will create conflicts in their fight for workers’ rights. A whole river of consequences sets in – no allowances for the retrainees, no retrainees, no organising. They have tried to run retraining classes out of their own resources but drowned by the river of consequences and the constant inadequacy of funds24. The classes were finally closed because there were not enough applicants. Their organising turns to the local community in that through their other activities, it aims at building up their image and reputation, and attracts more women workers to the centre. Rome is not built in one day and all paths lead to the same end. However, the lack of concerted initiatives deals a critical blow to their fight to protect a substantial proportion of women workers who have worked in their youth out of necessity, supplied the economy with new workers, but dumped and crushed when they get into their 40s. It is my sincere hope that this little research can breathe some fresh air into the stagnant sea of women workers organising in this city hailed as the model of free economy. DECODE – the pro-business government doesn’t give a damn to the workers’ rights. And I would like to end this report quoting Ah Bo, Chairwoman of the Hong Kong Domestic Workers General Union on her experience in the union: “I got involved in union organising not because I came across some problems. I did it because the sisters had no means to come together. 24 The formation of the Hong Kong Domestic Workers General Union gets critical financial support from the Oxfam Hong Kong. And the government will better heed our calls if we have a trade union. With the trade union, LDHs can catch more attention. When the media wants to cover this issue, they will come to us. So, it helps with our call for changes. Seven days after the union was formed, some sisters came to us to complain about a recruitment agency. They started as contract employees, and were cheated into signing as self-employed. We went to the agency trying to work out something. We had no idea what to do, but we knew that we had to be there during office hours. Otherwise, nothing could be done. So we charged to the office and unfurled the banner. I was very nervous, worrying that I could be seen. I was holding the banner real high up, covering my face. The company took our petition letter and promised that they would follow up. We then left and went for a snack at Hung Hom Train Station. It was about 2 hours after we left the office. We got a call from the company, saying that they were willing to revert to the original arrangement, and signed the contracts with the sisters. I felt excited. I thought, “Oh, it really works!” I was pretty encouraged by this action. When I turned up in protests on 4.18 and others, I was not afraid any more, and I showed my real face. I realised that it was no big deal and the trade union could really do something.” APPENDIX: Profile of the six local domestic helpers in the focus group (Names omitted as preferred by the LDHs. All of them have enrolled in the domestic helper training class at the training centre of the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions) Age Family Status Education DH course first DH job Number of jobs to Date 2 A 54 Married, 2 children Primary school July 2003 September 2003 B 44 Married, 3 children Secondary 3 1998 September 2002 C 31 Married, 1 child Secondary 1 October 2003 October 2003 2 D 42 Married, 4 children Secondary 2 October 2003 November 2003 1 E 45 Married, 2 children Secondary 2 April 2003 1998 11 F 40 Married, 2 children Secondary 1 November 2000 December 2000 36 5 Concurrent jobs now 1 family 2 hours/5 days/$40 1 family 6 hours/ 5.5 days/ $1200 a week 2 families --3 hours/1 day/$50 --4 hours/1 day/$40 1 family 3 hours/6 days/ $3000 a month 3 families --3 hours/3 days/$45 --2 hours/2 days/$50 --2 hours/1 day/$50 3 families --2-3 hours/one day/$50-$60 --several one- off jobs