Handout - Bargaining Power of Buyers

advertisement

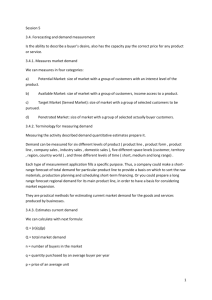

Handout for Business 189 undergraduate course in Strategic Management Bargaining Power of Buyers Simon Rodan Associate Professor Department of Organization & Management College of Business San José State University One Washington Square San José, CA 95192-0070 e-mail: simon.rodan@sjsu.edu Please do not quote or reproduce without the author’s prior agreement -1One way to begin thinking about the bargaining power of buyers is to ask how serious would it be for a firm in the industry to loose one buyer’s business. Put another way, what proportion of a firm’s output in the industry is bought by any one buyer. The proportion of a firm’s output a single buyer takes could be thought of as a first order measure of bargaining power. The two extreme cases that represent upper and lower bounds to this problem are when buyers spread their purchases evenly between all firms and when buyers place all their orders with a single firm. Buyers spread purchases evenly Firms Buyers Suppose there are F firms in our industry and B buyers to whom they sell. If all buyers are the same size and buy equally from each firm, then each buyer gets 1/F of what it needs from each firm and each firm sells 1/B of its output to each buyer. In the example in the diagram to the right, there are two firms and four buyers. Each buyer gets half its inputs from each firm and each firm sells a quarter of its product to each buyer. Here the loss of a single buyer would reduce out firm’s sales by 25%. As the number of buyers, B, increases the proportion of a single firms output sold to any one buyer falls. Note that the proportion of a firm’s output sold to a single buyer is independent of the number of firms in the industry. To illustrate this, suppose another firm enters the industry and all buyers now purchase from that firm also. Ignoring Cournot and price changes which apply best to fragmented markets (which this clearly isn’t), the amount sold to each buyer falls by 33%, as does the amount sold in total by each firm in the industry. However the proportions sold to each buyer remain unchanged. Thus the power of a buyer in this case is independent of the number of firms in the industry. Buyers focus on single suppliers Second, consider the case in which buyers ‘single source’ their inputs, that is, they buy from single supplier rather than spreading their purchases out across several firms. With B buyers and F firms, the number of buyers per firm is B/F (compared to F in the previous case). If firms have B/F buyers, then the proportion of output sold to one buyer is the reciprocal of -2this, or F/B. Fir first thing to note here is that F/B is greater than 1/B, the result from the first case. In other words, when buyers single-source, they take a larger proportion of a firm’s output so the first case is the best-case scenario for firms in the industry. As buyers focus their purchases more narrowly, the proportion of a firms output bought by each buyer rises, and with it, buyers’ barraging power. Firms Buyers The second point here is that if buyer power increases as buyers focus their purchases, they have an incentive to buy all they can from a single firm rather than spread their purchases across multiple suppliers. Of course this is a completely intuitive result. It’s also worth noting that here F has been assumed to be less than B; when F = B, we have a set of exclusively dyadic pairs or trading partners in which each firm supplies all its output to a single buyer which symmetrically sources all it’s requirements from one firm. When F > B, each buyer must source from multiple suppliers, but if buyers still maximize bargaining power, they will take all they can from a single firm which means 100% of each firms output. A few years ago, I was chatting with the owner of a small metalwork shop in San Carlos. He’d just been offered a contract to build parts for airport X-ray machines; the buyer in the case was the Department of Homeland Security. If he took the contract, he estimated he’d have enough work for at least 5 years taking about 50% of his production capacity. Yet, at least when I talked to him, he was leaning towards not taking the contract. This may seem strange – when someone offers you guaranteed work for 5 years that sounds like a gravy train. His problem was that he knew how demanding the government could be, and when a single customer is providing half your business you can’t really say no. And that could create pressure – for example if the DHS asked for shipments to be brought forward - that would interfere with the other half of his business. The bargaining power of a single buyer here was likely to be so great that he was leaning towards keeping his current customer base of smaller clients. So in summary, in a best case scenario, buyer power depends only on the number of buyers. In the worst case, buyer power declines with the number of buyers and increases with the number of firms in the industry. Since in considering rivalry we took into account the effect of increasing numbers of firms in the industry itself, we could think of bargain power as being what’s not accounted for by the structure of our industry, in other words the structure of the down- -3stream buyer industry. The last point to note here is that even when there are many firms in the industry (see inset), small firms can still decide to diversify their customer base if there are many potential customers. Firms get to choose scenario 1 to 2 above, and this choice applies quite generally, not only in the case of F < B considered here. Just as a large firm will supply many small customers a small firm can also – if it chooses to. The choice is whether to spend a great deal of effort going after many smaller customers who will not have very much bargaining power or one large one which will hold your feet to the fire. The only circumstance in which firms can’t make this choice is in a monopsony – when there are very few buyers. Another way to think about bargaining power is to ask the question of a transaction: “who can not afford to walk away from the deal”? Suppose you have a duopoly (two firms) and a duopsony (two potential customers). Here if both firms minimise their dependence on the two customers, each will be selling half their output to a single customer. Buyer power is high. Now suppose there are 10 firms in the industry instead of two. Does their number of potential customers change? No. Neither does the proportion of their product bought by each of their two customers. Few buyers Many buyers Few firms High Low Many firms High Low Bottom line (literally): Buyer power is all about the size/number of buyers.