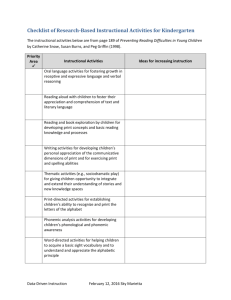

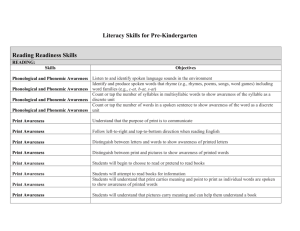

Preventing and Overcoming Reading Failure: Recent

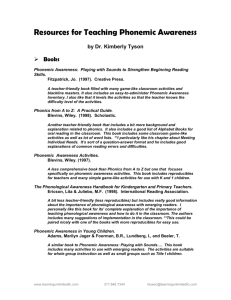

advertisement