Notes on Conversation with Mr. Bevin, March 22, 1947

advertisement

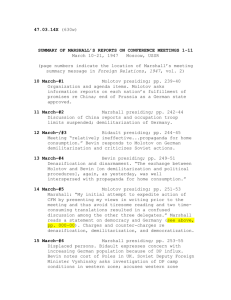

47.03.22B (1559w) NOTES ON A CONVERSATION March 22, 1947 WITH MR. BEVIN [Moscow, USSR] Mr. Bevin called on me at 12:45 and left at 2:30. We had lunch together. GREECE He first brought up the question of Greece. Mr. Bevin stated that the British Cabinet had agreed to meet the proposal of Mr. Acheson that the British carry the financial crisis in Greece after March 31, until our Congress had had an opportunity to act. Bevin said Britain had committed 18 million pounds for this purpose. He then stated that he had transmitted my request that the British not withdraw their military mission and the Cabinet have agreed not to withdraw it for the time being, and also to maintain the naval, air and police missions. However, in order to provide funds for the military mission, it would be necessary under their system to go back to Parliament, which would be a very undesirable procedure, having just obtained an authorization for 18 million pounds additional on the Greek situation. It was therefore the proposal of the British that some other arrangement should be made to meet the expenses of the mission and I believe Bevin said the British Government also proposed that the cost of the mission should be defrayed by the Greek Government, presumably out of money loaned by the American Government. He did not ask for a reply by me at this time, but 1 requested that I give it consideration. REPARATIONS: Mr. Bevin stated that he had only attended the Potsdam Conference during its last four days, arriving Saturday and the Conference completing work the following Wednesday, and had a very brief time to gain impressions. He himself was not clear on the over-riding completeness of the Potsdam Agreement on reparations in relation to the previous tentative agreement at Yalta.1 In other words, he did not feel that reparations from current production were by the Potsdam Agreement completely barred. Mr. Bevin reiterated his statements that the British Government would not commit itself to any reparations out of current production until Germany had been made self-sustaining. Mr. Bevin then inquired how fixed our stand was regarding reparations from current production—to what extent were we determined to stand on our statement that there should be no retreat from Potsdam to Yalta. I told Mr. Bevin that we were clear in our minds, particularly those gentlemen who had been present at both Yalta and Potsdam, that the Potsdam Agreement completely superseded the Yalta expressions regarding reparations. I summarized our view of the existing situation, that is (a) the fact that the transfer of plants and machinery generally had not been a profitable procedure (b) that the Soviets by their policy of a five-year plan for the building up of the military potential of their government now found themselves in a difficult, if not desperate, economic plight in some sections of the country and therefore would be the more determined in their negotiations to obtain reparations from current production, 2 particularly during the next two years (c) that we had been examining the situation to see if there might not be some procedure such as the operation in Germany of reparations plants for the benefit of the Soviets, they providing the raw materials, etc., which would permit a form of reparations from current production without delaying the creation of a self-supporting German economy. I indicated the political impossibility of securing agreement by an American Congress to a course of action which involved the indirect payment of reparations and I opposed this with the view that the Soviet demand for some form of reparations out of current production during the next two years would be implacable. Mr. Bevin said that he felt that it would require very expert investigation to determine whether or not such a course of operating reparations plants in our zones for the benefit of the Russians, they furnishing the raw material, was practical.2 He then turned to his relations with the French and explained that he had agreed prior to coming to Moscow on at least two occasions to delay any cut in the export of coal deliveries because of critical French election situations, but finally had been forced to advise Mr. Blum that he could go along no longer on that basis, that critical repairs would have to be made in order to really get ahead on the matter of production and had counseled a frank statement to this effect by Mr. Blum to the French people.3 Then Bidault had approached him for another delay and later had stated that unless a suitable adjustment in coal was made for France, the French could not go through with this conference regarding other matters. He had told Bidault that that was not acceptable procedure and advised 3 him not to bring it up in the Conference. However, it had been brought up and I had heard his remarks on the subject. He added that they were made as much for Molotov’s benefit as for Bidault’s—that he was opposing this business of stating that unless there was an agreement on one point, they would not go ahead on others, and that it would be his course throughout the Conference. He would not submit to such procedure. He stated, incidentally, that Mr. Molotov had been trying to draw him on the reason for the slow development of the capacity of the Ruhr mines, which in Mr. Bevin’s opinion was caused by his concession to the French to meet their political crisis which had thus delayed the genuine reconditioning of the mines. There followed a discussion on the Polish boundaries, density of population, and related matters, during which Mr. Bevin gave expression to no definite and important points of view. He did not state what the stand of the British Government would be on the subject. I failed to mention in the first place that I told Mr. Bevin that the American Delegation felt that it was very important to make no concessions, especially at this time, if ever, on the Potsdam Agreements, particularly as related to reparations. NA/RG 59 (Central Decimal File, 868.00/3–2247) 4 1. There had been considerable discussion at the Yalta Conference about reparations, beginning at the plenary session on February 5 when the Soviets first raised the issue of receiving $10 billion in reparations from Germany. One of the documents emerging from the Yalta Conference was the “Protocol on the Talks Between the Heads of the Three Governments at the Crimean Conference on the Question of the German Reparation in Kind,” signed by Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill on February 11, 1945. In it they agreed that “Germany must pay in kind for the losses caused by her to the Allied nations in the course of the war.” A US-UK-USSR reparations commission was to be established in Moscow. The protocol quoted the following agreement by the Soviet and American delegations: “The Moscow Reparation Commission should take in its initial studies as a basis for discussion the suggestion of the Soviet Government that the total sum of the reparation...should be 20 billion dollars and that 50% of it should go to the Union of Soviet Socialists Republics.” The protocol also noted, however, that “The British delegation was of the opinion that pending consideration of the reparation question by the Moscow Reparation Commission no figures of reparation should be mentioned.” (Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States: The Conferences at Malta and Yalta, 1945 [Washington: GPO, 1955], pp. 619–23 [plenary session], 982-83 [protocol].) Because of the reparations controversy, the State Department released this protocol to the press on March 24, 1947.) Following further discussions of reparations during July 1945 at the Potsdam Conference, the August 1 “Protocol of Proceedings of the Berlin Conference” included a section 5 on the subject. The Allies agreed that: (1) Soviet claims to reparations were to met by removals from their zone of Germany; (2) the Soviets were to settle Polish claims from their own share of German reparations; and (3) the Soviets were to receive from the British and American zones “15 per cent of such usable and complete industrial capital equipment...as is unnecessary for the German peace economy ...in exchange for an equivalent value of food, coal,...and such other commodities as may be agreed upon. [And] 10 per cent of such industrial capital equipment as is unnecessary for the German peace economy...without payment or exchange of any kind in return.... The amount of equipment to be removed from the Western Zones on account of reparations must be determined within six months from now at the latest.” (Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States: The Conference of Berlin (The Potsdam Conference), 2 vols. [Washington: GPO, 1960], 2: 1485–86.) A summary of the US position during the Potsdam Conference is in the extract of “Report on German Reparations to the President of the United States, February to September 1945, September 20, 1945,” ibid., pp. 940–49. 6 2. Bevin wrote Marshall on March 23 that the British government would reject “any settlement of the German problem involving reparation from current production” which would require the British to increase expenditures. (Foreign Relations, 1947, 2: 274.) 3. Léon Blum, twice prime minister of France (1936–37, 1938), had been chairman of the Provisional Government and minister of foreign affairs between December 16, 1946, and January 22, 1947. 7