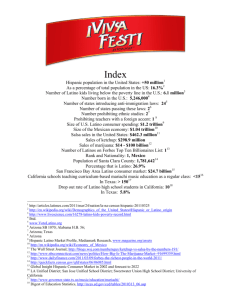

click here

advertisement