HOW TO LEARN WEIQI (GO GAME) FOR FUN AND HARMONY IN

advertisement

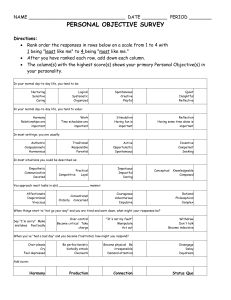

LEARN WEIQI (GO), THE HARMONY CULTURE GAME, FOR FUN Presenter: Francis C W Fung, Ph.D., Director General, World Harmony Organization Education: B.Sc. Aeronautical Engineering, Brown University M.S. Fluid Mechanics, Johns Hopkins University Ph.D. Aerospace Engineering, University of Notre Dame Dr. Fung is an aerospace engineer by profession. His multidiscipline experience includes energy and harmony research, U.S. – China technology transfer, academic teaching of fluid mechanics, international commerce, and creative thinking. As Director General of the World Harmony Organization, he is a prolific writer. His articles on Harmony Renaissance, Harmony Culture, Harmony Diplomacy, Harmony Governance, and Harmony Faith appear regularly worldwide on leading international media and websites. From Shibumi, bestseller by Trevanian Those interested in impressing others with their intelligence play chess. Those who would settle for being chic play backgammon. Those who wish to become individuals of quality, take up Go [Weiqi]. Weiqi, the ancient Asian chess game, is all about harmony philosophy and extending influence by people soft power. It is about sharing through extending influence and not confrontation. Also known as GO in some parts of the world, Weiqi is played by two with 361 equally ranked black and white stones (influences). Players take turns to deploy a stone of their color one at a time to gain more presence (influence) on a board with 19X19 horizontal and vertical intersecting lines (in the full version) representing potential points of influence. The objective is to extend influences across the playing board, and not to annihilate the opponent’s influence or pieces, leading to capturing the king as in western chess. When equally matched, players usually win by only a few extra stones on the board. Weiqi is easy to learn and fun to play, but hard to play well. It requires good mental discipline, a deep philosophical attitude, and a multi-campaign mentality. Unlike western chess, the best known computer program still loses to the best Weiqi human player, despite the advances of computer programming. Western chess is basically a game of attack in which you must take your fight to the enemy to win; you will not win just defending. In contrast, with Weiqi’s objective of spreading influence, one generally only captures opponents if it is for strategic locations and when in ones acquired sphere of influence. It is never efficient to capture just for capture’s sake. According to tradition, Weiqi was thought to have been invented by the first legendary sage king of China, the great Yao Shun, to teach his son to be a future wise king. To extol the harmony philosophy of Yao Shun, Confucius said in the Classic Zhongyong, “Great indeed is the wisdom of Shun! Shun likes to ask and to investigate the words of those who are close to him. He omits the bad and propagates the good. He holds fast the two extremes and uses the in-between for the people. This is what makes him Shun!” In Confucius’ harmony philosophy, from the two extremes comes the in-between. Only where there is a third that is the in-between of the two can the dispute be resolved and harmony be achieved. When there is no third, no in-between, the two will compete and fight with each other. This will lead to mutual destruction and not harmony. In ancient China, Weiqi was given the second most important position as the “must learn” discipline, along with Ku Zeng, poetry, and calligraphy, for accomplished scholars. Both Confucius and Lao Tze considered playing Weiqi as an important accomplishment for a Confucian scholar. In Asia there were also important talented ladies recorded in history who excelled in playing Weiqi. Today it is played for fun and big prize money. In modern Japan, Weiqi has attracted as many amateur female as well as male players. In modern days, among some learned circles in both East and West, Weiqi is considered as must training of business acumen for prospective entrepreneurs, along with reading Sun Tzu’s “Art of War”. It is also a recommended game at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point for counterterrorist influence training. For today’s multilateral world, Weiqi is essential training for our youth to learn how to share in a multi-ethnic and multicultural planet. Weiqi exercises both sides of our brains in spatial and analytical skills and cultivates our use of nonconfrontational soft approaches. It will be a desirable skill that will enable us to live in harmony with ourselves and with the world around us. It is a diplomat’s game to learn for the 21st century multilateral world. In this workshop, we will do a lot of practice playing between beginner students guided by experienced teacher players. By the end of this short workshop, you will have a strong feeling of accomplishment in playing and will come away with a good sense of Weiqi harmony culture. Ultimately, the play of Weiqi is a shared negotiation and not simply outright conquest nor religious influence combined with military power, as in Western chess.— photo from Wikipedia BEGINNER WEIQI (GO) AND INTERACTIVE PLAYING THE CLASS WILL BE CONDUCTED IN ENGLISH WITH BOTH ENGLISH AND CHINESE TERMS. STUDENTS WILL BE GIVEN A LOT OF OPPORTUNITY TO PLAY WEIQI WITH TEACHER GUIDANCE. THROUGHOUT THE COURSE, WEIQI PHILOSOPHY WILL BE DISCUSSED BY STUDENT PARTICIPATION USING KNOWLEDGE LEARNED FROM THE CLASS AND OUTSIDE READING. THE CLASSES WILL BE CONDUCTED WITH INTERACTIVE EXAMPLES AND LECTURES ON HISTORY AND THE WEIQI HARMONY PHILOSOPHY. (FOR EXAMPLES, SEE INTRODUCTION AND WEIQI QUOTABLE VIEWS HANDOUT.) STUDENTS WILL BE GIVEN EXERCISES TO PRACTICE AFTER CLASSES. 1) WEIQI AND PHILOSOPHY INTRODUCTION; LEARN TO MAKE A WEIQI BOARD 2) THE RULES OF WEIQI AND DEMONSTRATION GAMES 3) ELEMENTARY TACTICS AND STRATEGY 4) GRAND STRATEGY AND PLAYING 5) EXAMPLE GAMES WITH COMMENTARY AND INTERACTIVE TEACHING 6) CLASS TOURNAMENT AND SPEECH CONTEST; PRIZE AWARDS FOR TOURNAMENT, SPEECH, AND PARTICIPATION WINNERS. THREE EQUAL HONOR CLASS PRIZES OF YOUNZI CHESS STONES SETS WITH WOODEN BOWLS WILL BE AWARDED TO THREE TOP-PERFORMING STUDENTS. YOUNZI STONES ARE CLASSIC CHINESE STONES FROM YUNNAN PROVINCE USED IN CHINESE WEIQI TOURNAMENTS. PRIZES WILL BE DONATED BY CLASS SPONSOR. THE SPEECH COMPETITION TOPIC WILL BE “WHAT I HAVE LEARNED FROM PLAYING WEIQI”, A WRITTEN SPEECH OF ABOUT 5 MINUTES. WINNER WILL BE SELECTED BY STUDENT VOTING. THE SECOND EQUAL PRIZE FOR TOP CLASS PARTICIPATION AND MOST HELPFUL STUDENT WILL ALSO BE SELECTED BY STUDENT VOTING. THE TOURNAMENT WINNER WILL BE AWARDED THE REMAINING WEIQI SET. THE LAST CLASS WILL BE THE AWARD CEREMONY WHEN THE TOP THREE SELECTED SPEECHES WILL BE DELIVERED. PARENTS OF THE CLASS STUDENTS ARE INVITED TO ATTEND. Francis C W Fung, Ph.D. Director General World Harmony Organization San Francisco, CA Edited by James C Townsend, Ph.D. Director, World Harmony Organization francis@worldharmonyorg.net What is GO? Viewpoints . . . [it is] something unearthly . . . If there are sentient beings on other planets, then they play Go. – Emanuel Lasker, chess grandmaster Go uses the most elemental materials and concepts -- line and circle, wood and stone, black and white -- combining them with simple rules to generate subtle strategies and complex tactics that stagger the imagination. – Iwamoto Kaoru, 9-dan professional Go player and former Honinbo title holder There are on the Go board 360 intersections plus one. The number one is supreme and gives rise to the other numbers because it occupies the ultimate position and governs the four quarters. 360 represents the number of days in the [lunar] year. The division of the Go board into four quarters symbolizes the four seasons. The 72 points on the circumference represent the [five-day] weeks of the [Chinese lunar] calendar. The balance of Yin and Yang is the model for the equal division of the 360 stones into black and white. – From The Classic of Go, by Chang Nui (Published between 1049 and 1054) The board has to be square, for it signifies the Earth, and its right angles signify uprightness. The pieces of the two sides are yellow and black; this difference signifies the Yin and the Yang — scattered in groups all over the board, they represent the heavenly bodies. These significances being manifest, it is up to the players to make the moves, and this is connected with kingship. Following what the rules permit, both opponents are subject to them — this is the rigor of the Tao. – Pan Ku, 1st century historian Beyond being merely a game, to enthusiasts Go can take on other meanings: of a nature analogous with life, an intense meditation, a mirror of one’s personality, an exercise in abstract reasoning, or, when played well, a beautiful art in which Black and White dance across the board in delicate balance. – Terry Benson Unlike chess and its different pieces and complicated rules, Go is played with black and white stones equal in value, seemingly making it compatible with the binary nature of computers. Since the aim of a move is to control the most territory, the optimal move yields the maximum amount of territory — a simple counting procedure and a chore computers excel at. Yet in spite of the efforts of the world’s best programmers over the last 30 years, the level of computer Go remains about that of a human who has studied Go for a month. – Richard Bozulich Studying go is a wonderful way to develop both the creative as well as the logical abilities of children because to play it both sides of the brain are necessary. – Cho Chikun, among the world’s strongest players and one of the three great prodigies in Go history The difference between a stone played on one intersection rather than on an adjacent neighbor is insignificant to the uninitiated. The master of Go, though, sees it as all the difference between a flower and a cinderblock. Certain plays resonate with a balletic grace, others clunk, hopelessly awkward, and to fail at making the distinction is a bit like confusing the ping of a Limoges platter with the clink of a Burger King Smurfs tumbler. – From The Challenge of Go: Esoteric Granddaddy of Board Games, by Dave Lowry That play of black upon white, white upon black, has the intent and takes the form of creative art. It has in it a flow of the spirit and a harmony of music. Everything is lost when suddenly a false note is struck, or one party in a duet suddenly launches forth on an eccentric flight of his own. A masterpiece of a game can be ruined by insensitivity to the feelings of an adversary. – From The Master of Go, by Yasunari Kawabata, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature Go is to Western chess what philosophy is to double entry accounting. – From Shibumi, bestseller by Trevanian Those interested in impressing others with their intelligence play chess. Those who would settle for being chic play backgammon. Those who wish to become individuals of quality, take up Go. – Microcomputer Executive and an expert player, when asked to compare Go with other games Monks who have a talent for it play go with women and become their lovers. – Yamaoka Genrin, Edo-period essayist There are Oriental folk tales reminiscent of Rip Van Winkle in which people have been stopped by an old man [one of the Immortals], played a game of Go, and upon getting up from the board have found a hundred years have gone by. This purely mental aspect of the game is in its intellectual dynamic. These Chinese had seen it as encompassing the principles of nature and the universe and of human life, as the diversion of the immortals, a game of abundant spiritual powers. – From The Game of Go, by Robert Buss You’re striving for harmony, and, if you try to take too much, you’ll come to grief. – Michael Redmond, American Go player when 23 years old and already a 5-dan professional About three hundred years ago an eminent Chinese monk came to Japan on a visit and was shown the diagram of a game of Go which a master of that time had recently played. Without knowing anything of the game save the sketchy description they gave him, the monk studied the moves as shown on the record, and after a few moments remarked with much admiration and respect that the player must have been a man who had become enlightened, which was indeed the case. It is interesting to note that this story is told on the one hand by Go players to illustrate the quality of the game and on the other hand by Buddhists to show the acuity of the monk from China. – From Go and the Three Games, by William Pinckard The board is a mirror of the mind of the players as the moments pass. When a master studies the record of a game he can tell at what point greed overtook the pupil, when he became tired, when he fell into stupidity, and when the maid came by with tea. – Anonymous Go player Go and the ‘Three Games’ by William Pinckard Games-playing is one of the oldest and most enduring human traits. Disparate pieces of evidence such as dice discovered at Sumer, game-boards depicted on Egyptian frescoes, Viking chess pieces, and ball parks constructed by ancient empires deep in the Andes link up directly with contemporary phenomena such as Saturday night poker games in Kansas City and the annual go title matches in Tokyo. Games are undeniably a concomitant of civilization and even in their most primitive forms presuppose some degree of sophistication. Most of all, they require the ability to think in abstractions and to manipulate ideas in logical terms, thereby giving form to what is formless and creating small, recognizable patterns in the shadow of great mysteries. From ancient times in Japan the so-called ‘Three Games’ were backgammon, chess and go. Chess probably comes from India, backgammon from the Near or Middle East, and go from pre-Han China. Backgammon is a gambling game which, using dice, gives luck or chance the preponderant role. Chess in one of its earlier forms also used dice, but takes its present shape from the structure of a royal society and from war maneuvers. Go is the most abstract and ‘open’ of the three; and with its freedom from complicated rules, its simplicity of form, its fluidity and spaciousness, it comes remarkably close to being an ideal mirror for reflecting basic processes of mentation. Go is played with black and white ‘stones’ all of exactly the same value, thus somewhat resembling the binary mathematics which is the basis of the computer. The stones are played onto the board and are left as they stand throughout the game, so that the game itself takes shape as a visible record of the thinking that went into it. About three hundred years ago an eminent Chinese monk came to Japan on a visit and was shown the diagram of a game of go which a master of that time had recently played. Without knowing anything of the game save the sketchy description they gave him at the time (this was after go had more or less died out in China), the monk studied the moves as shown on the record and after a few moments remarked with much admiration and respect that the player must have been a man who had become enlightened -- which was indeed the case. (It is interesting to note that this story is told on the one hand by go players to illustrate the quality of the game and on the other hand by Buddhists to show the acuity of the monk from China.) The great 17th century Japanese playwright Chikamatsu, in a famous passage, compares the four quarters of the go board to the four seasons, the black and white stones to night and day, the 361 intersections of the board to the days of the year, and the center point on the board to the Pole Star. It would be easy to erect a tower of fanciful theory along these lines, but that would only obscure the obvious point. In this striking analogy Chikamatsu is describing a feeling of hugeness and all-inclusiveness -- the board conceived as a complete world system in potential form. The board and pieces can be thought of as limitless: any number of lines and an endless supply of stones to play with, the game itself being the life of the players. (In Chikamatsu’s play a young man becomes old and grows a long beard while watching a single game.) Only because we are human and must put practical limits to our activities, do we use just a small part of the infinite board. But this field of nineteen by nineteen is large enough to contain everything we are able to put into it. The number of possible games playable on this board has been reckoned to be more than the number of molecules in the universe. An anonymous go player has written: ‘The board is a mirror of the mind of the player as the moments pass. When a master studies the record of a game he can tell at what point greed overtook the pupil, when he became tired, when he fell into stupidity, and when the maid came by with the tea.’ Contrary to the opinion of many people, go has nothing to do with Buddhism. Because it is a valid system in itself, it offers nothing contradictory to other systems, but in fact go is an older inhabitant on this planet than is Buddhism. In China it became one of the Four Accomplishments, the others being poetry, painting and music. It reached Japan around the 6th century and for a long time remained the exclusive property of a leisured noble class. Then during the 16th century all this changed. The many great families and clans which had warred happily against each other for a thousand years were gradually brought under the hegemony of the Tokugawa Shogunate. It was during the subsequent period of the Tokugawa era (roughly from 1600 to 1868) that go, along with haiku, kendo, tea ceremony and so on, was most actively cultivated as a way of constructively channeling the mental energies of the people during the long years of peace. One formal word for go in Japanese is Kido. Ki is the old Chinese word for go, and -do is the Chinese word for Tao, which means Way -- or, more specifically, a Way to enlightenment. All games channel mental energies, whether they lead to enlightenment or the reverse, but it is suggestive to consider the ‘Three Games’ in their social context because then we can see how each of them reflects certain basic characteristics of a general or regional type. Chess, for example, the great historical game of the West, involves monarchs, armies, slaughter, and the eventual destruction of one king by another. The game appears to be entirely directed along the lines of the great myths of the West from the Mahabharata to the Song of Roland -- the overthrow of a hero and the crowning of a new hero. The pieces, from king down to pawn (peon), give a picture of a hierarchical and pyramidal society with powers strictly defined and limited. Backgammon, the favorite game of the Near and Middle East, is preoccupied with the question of Chance and Fate (Kismet). All play is governed by the roll of dice over which the player has no control whatever. The players are matched against each other, but each tries to capture a wave of luck and ride it to victory. The loser curses his misfortune and tries again, but the individual is helpless in the grip of superior forces. Go, the game of ancient China and modern Japan (and now popular throughout the world), is unique in that every piece is of equal value and can be played anywhere on the board. The aim is not to destroy but to build territory. Single stones become groups, and groups become organic structures which live or die. A stone’s power depends on its location and the moment. Over the entire board there occur transformations of growth and decay, movement and stasis, small defeats and temporary victories. The stronger player is the teacher, the weaker is the learner, and even today the polite way to ask for a game is to say ‘Please teach me.’ Things are different now, but in earlier times, when go was so much admired by painters and poets, generals and monks, the point of the game was not so much for one player to overcome another but for both to engage in a kind of cooperative dialogue (‘hand conversation’, they used to call it) with the aim of overcoming a common enemy. The common enemy was, of course, as it always is, human weaknesses: greed, anger and stupidity. Every year in March department stores all over Japan present elaborate displays in connection with the Doll Festival. If one looks carefully at the miniature weapons, musical instruments and furniture of a really complete display one will find a tiny backgammon board, a Japanese chess (shogi) board and a go board. The ‘Three Games’ is a useful classification because taken together they make up a coherent world view. Most of philosophy boils down to speculation centered around the three basic relationships of the human species. The first is man in his relationship to the remote gods and the mysterious forces of the universe. The second is man in the society he builds up around him. The third is man in his own self. Or, to put it another way, man the backgammon-player, man the chess-player, and man the go-player. That we have these three shows that they answer basic needs in the human spirit. People everywhere are preoccupied with social structures, position and status; and everyone who is capable of reflection must sometimes speculate on his private relationship to fortune and fate. But go is the one game which turns all preoccupations and speculations back on their source. It says, in effect, that everyone starts out equal, that everyone begins with an empty board and with no limitations, and that what happens thereafter is not fate or wealth or social position but only the quality of your own mind. — photo from Wikipedia