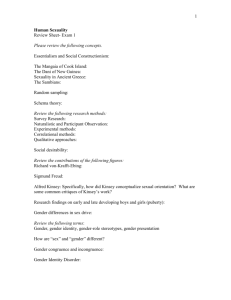

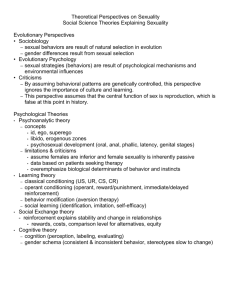

Aspects of education - Illinois Coalition Against Sexual Assault

advertisement