EQL 04 Constitutional Law I

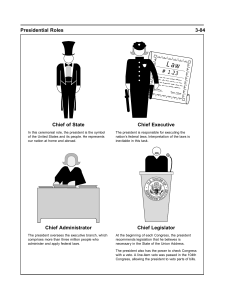

advertisement