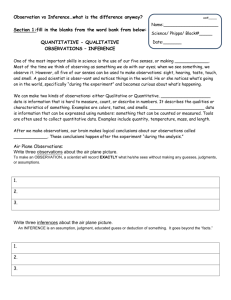

associative, inductive and deductive inference operations in

advertisement

INFERENCE OPERATIONS IN

DECISION SITUATIONS

Decisions exercises can generally be thought of being engined by one of three types of inference apparatus

(which correspond to the three different categories of cognitive capabilities that constitute human

intelligence):

ASSOCIATIVE

INDUCTIVE

DEDUCTIVE

One way of getting at the distinctions among these three inference modes is draw on a simple InputProcessing-Output type construct:

Predicates

Decision Choice

Experience,

Facts or

Empiricals

Inference Operations

Conclusion

Instrumental and/or

Intellectual Mediation

Of the several modes, associative inference involves the least in the way of intelligent mediation, meaning

that conclusions are intimately tied to facts (or strongly anchored in empiricals or experience). Inductive

inference (which, strictly speaking, involves moving from the more particular to the more general) is the

medium that allows us to arrive at conclusions that go somewhere beyond experience, precedent or the bare

facts of a matter…but not too far beyond them. Deductive inference, on the other hand, generates

conclusions that are only very weakly tied to —i.e., transcend— empiricals, experience or precedent.

Deductive inference capabilities may be taken as the highest expression of human intelligence enabling the

development of "original solutions to novel problems"; it's the engine of creativity, in effect.

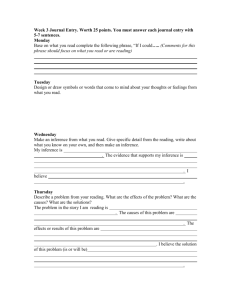

I. ASSOCIATIVE INFERENCE

Simple associative inference is the least demanding of the several modes in terms of the level of

intelligence (or cognitive capability) that's required. At its most elementary, associative inference is a

product of direct experience (I won't ever smoke any more of that stuff!) or classical conditioning (as per

Pavlov's dogs). Associative inference based behaviors can also be a product of collective experience that's

codified and passed down as "lore", indoctrination or rote learning. In any of its guises, associative

inference is the generally preferred —sufficient and efficient—medium for dealing with routine, repetitive

situations or well-precedented problems, as decision will be arrived at more or less automatically…with

minimal reflection and/or expenditure of analytical effort. On the downside, associative inference is not an

appropriate medium for coping with novelty, accommodating change or recognizing fine distinctions, etc.

Thus, over-reliance on associative inference apparatus is a hallmark of both primitive (tradition-bound)

societies and primitive intellects (those who are overly fond of generalization, as it were).

In organizational contexts, functionaries whose analytical responsibilities can be met via

associative inference capabilities can be comprehended as operating under what amounts to a decisiontable type logic:

O Em Rm :

{O}

Observables

EVENTS

E1

E2

…

Em

R1

R2

...

Rm

As an example, consider the paramedic:

1). He/she will have been taught to recognize some number of discrete medical events (broken arm, hypothermia,

incipient heart attack, etc.) that might be encountered in the field. More specifically, he will have been taught to

recognize the particular array of symptoms uniquely associated with each of these medical events. Therefore,

when encountering an emergency situation, the first task is for the paramedic is to map from the symptoms

(observable conditions) exhibited by the victim to a particular medical event: if {O} then Em.

2). The domain of a paramedic's competence is then bounded by the membership —in terms of breadth and

diversity, etc.— of the event set [E]. Paramedic's may then be deemed more or less capable depending on the

breadth and diversity of the set of medical events they have been formally trained to handle. But there is this

practical qualification: Paramedics will (generally, at least) not be expected to operate under conditions of

diagnostic ambiguity. Rather, associative mappings between symptoms (observables) and events (medical

syndromes) must be essentially deterministic, such that P(O (Em [E]) 1, i.e., the probability (P) that a

particular set of symptoms (O) points to a singular member of the event set (Em) is approximately equal to one,

thereby authoring a situation of effective certainty. In all other instances, paramedics would be required to

immediately pass the problem forward to a higher authority (e.g., make radio contact with an emergency room

physician and follow whatever advises are forthcoming). Or, in the absence of a real-time communication link of

this sort, there will probably be a generic default directive requiring paramedics to restrict intervention to the

minimum necessary to keep the victim alive until delivered to a hospital).

3). Anyway, for any given medical event, there will be one and only one appropriate/authorized response option

or course-of-treatment a paramedic is expected to enact. The content of a decision table thus consists of a set of

directive (associative) rules: if Em then do Rm. There is, then, little or no occasion for any discretion on the

part of the paramedic as to how medical conditions are to be handled.

Other examples of those whose decision responsibilities are rooted in associative inference are minor

bureaucrats operating "by the book" and military officers whose discretion on the battlefield is curtailed by

"rules of engagement", etc.

If one thinks of a decision table as constituting an information base, then we can also think of the

substance of associative inference driven decisions as being given; that is, the content of conclusions is, in

effect, predetermined by the content of the information base qua decision table. It's this that makes those

charged with carrying out decision-table like activities in any organization the prime candidates for

displacement by computers!

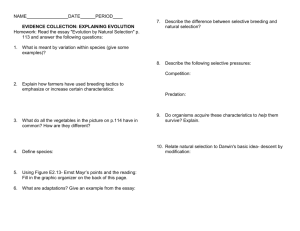

II. INDUCTIVE INFERENCE

Inductive inference invokes a higher level of cognitive capability than its associative counterpart

(and is a product of a more complex "learning" process as well … Operant vs. classical conditioning). In

essence, inductive inference apparatus enables generalizations, i.e.: Reasoning from the more particular to

the more general. Inductive inference thus leads to conclusions that involve a substantive extension of

experience, thereby allow us to move beyond what's already known (facts), what's already taken place

(precedent) or what's previously been learned (education, formal or otherwise).

A good bit of work has been done by analytical philosophers (mainly student and practitioners of

the Empiricist school, notably Carnap and his immediate successors) in devising rules to bring formal logic

discipline to inductive reasoning. More generally applicable to managerial decision-making, however, is a

pragmatic variant, ampliative inductive inference. To discipline decisions authored under ampliative

inductive inference, there is a wide variety of analytical instruments (statistical, most familiarly) derived

from the computational vis logical form of inductive inference, mathematical probability theory. There

are three variations on ampliative inductive inference:

LONGITUDINAL [constructing a future as a function of the past], the most obvious

managerial application of which is forecasting via a statistical-inference instrument (CorrelationRegression, Least Squares methods or econometric formulations of the BLUE variety …Best

Linear Unbiased Estimator) operating on historical data arrayed as a Time Series.

CROSS-SECTIONAL [arguing from the local to the universal], or the imputation of

properties to a population as a whole on the basis of attributes or behaviors observed in some

sample…as with market research exercises (usually cast as ANOVA-based experimental designs)

that use preferences exhibited by a limited number of individuals in test groups to infer to the

probable predilections of the broader community of consumers.

ANALOGIC [e.g., attempting to make a current event at least partially comprehensible in

terms of empirical precedents], or employing secondary evidence —observations made with

respect to some other subject, or data originally collected in or pertinent to some other context— to

impute properties to some new situation (e.g., defining prospects for a new product in terms of

market results obtained for more or less similar products elsewhere).

The rectitude/precision of longitudinal ampliative inductive inferences is sensitive to variance in

the historical data records (the 'spread' of the Time series). The confidence with which cross-sectional

inferences can be applied depends on the consistency of the sample results and the apparent

'representativeness' of the sample itself. The integrity of analogic inductive inferences is tied to the strength

of contextual correlations between the precedent(s)/setting in which evidence was originally collected and

the situation to which it now to be applied. Incidentally, weak contextual correlations can also compromise

cross-sectional inferences (as with the "new" Coke debacle).

In terms of technical implications, the difference between associative and inductive inference

operations corresponds roughly to the difference working under a decision table vs. decision tree, in that the

latter involves probabilistic (as opposed to deterministic) mappings, i.e.:

Observables to Event(s):

O (Em, Ej …) [E] and Pmax (Em [E]) 1

That is, there is no some degree of ambiguity to contend with, as observables will now point to two or

more event possibilities, with even the maximum-likelihood mapping (O Pmax Em) carrying a

probability significantly less than unity…or, alternatively, a significantly positive level of uncertainty.

Event to Response(s):

Em (Ri, Rj …) [R] and Umax (Rm [R]) 1

Instead of neat one-to-one mapping between event and responses, there's now two or more response

options that might be used to treat any Em and/or residual doubts about the efficacy of the assumedly

maximal-utility (Umax) choice.

In another sense, if the exemplary of an associative-inference functionary was the paramedic, the inductive inference

counterpart would be the physician. The latter (in large measure because his training in the 'principles' of medicine) is

presumably prepared to deal with diagnostic ambiguity (to make diagnoses that have some conjectural aspect to them)

and allowed —within the rather broad limits of acceptable professional practice— considerable discretion in

determining how any particular medical condition is to be treated.

III. DEDUCTIVE INFERENCE

In one of its strict or formal interpretations, deductive inference defines the process of reasoning

from the general to the particular (e.g., the application of broad theoretical provisions to some problem). A

more pragmatic appreciation has deductive inference operations leading to conclusions that are strongly a

prioristic or judgmental in content. Deductive inference driven decisions would thus owe relatively little to

facts, experience or empirical referents of any kind, much to conjecture, imagination or opinion (learned or

otherwise). Deductive inference driven behaviors span a continuum anchored on the one end by the

rigorous, axiomatic-type reasoning underlying hypothesis-formulation in fields like archaeology,

astrophysics and certain areas of mathematics (modern algebra, for example), and towards the other by raw

rhetoric, idle speculation or unbridled intuition…and, maybe, madness.

As a practical matter, deductive inference would be called on when inductive inference

capabilities cannot cope: (a). In contexts where the future is likely to be significantly different in kind from

the past, (b). Where factual and/or empirical decision predicates are extremely scarce (as in innovationdependent industries, with their premium on depriving competitors of any "hard" information about

product-development intents), or (c). When the situation at hand is essentially novel, such that there are no

applicable precedents.

In terms of technical implications, deductive inference based decision situations pose a

requirement for two types of facilities that the management/systems sciences are not as yet well-positioned

to provide:

concept-processing vs. data processing provisions.

analytical instruments to ensure the rationality of judgment-driven decisions.

The continuing absence of such facilities represents perhaps the most critical of the technical shortfalls that

need to be addressed so far as managerial matters are concerned…in all sectors, not just the commercial!

METAPHORS

Associative Inference:

A photograph that as faithfully as possible reproduces

the original subject

Inductive Inference:

A somewhat idealized portrait that diminishes flaws or

emphasizes assets; caricatures as per political cartoonists.

Deductive Inference:

Abstract art, where the finished product bears only

scant resemblance to the original subject