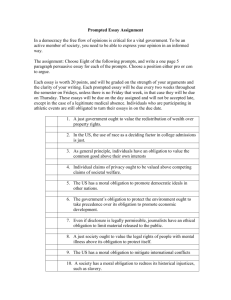

WORD

advertisement