CHY4U1 - Victoria Park Collegiate Institute

advertisement

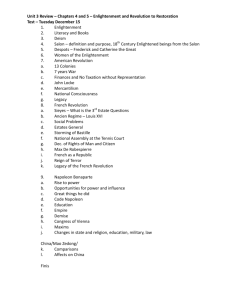

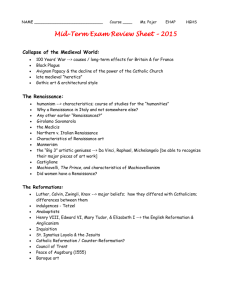

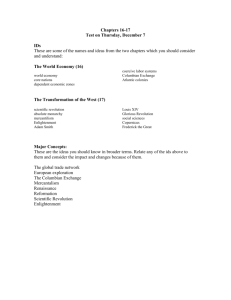

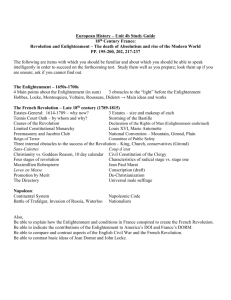

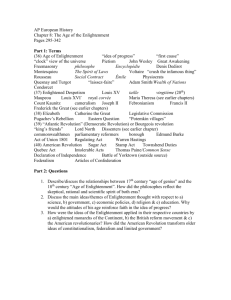

VICTORIA PARK COLLEGIATE INSTITUTE Teacher: Ms. Maize Email: susan.maize@tdsb.on.ca Location: History office, rm. 313 ACL: Mrs. Bremner The West and the World CHY4U Prerequisite Any University preparation course in Canadian and World Studies, English or Social Sciences and Humanities may qualify as a pre-requisite. If you have taken ‘M’ level grade 11 courses (University/College preparation), it is VERY strongly recommended that you come into this course with a (minimum) 75% average. This is a University level course—it is assumed that you have a variety of skills prior to the beginning of the course. There is a LOT of reading, writing and research required. Course Description This course is a ‘survey course.’ This means that we will be covering a variety of events, people and developments in the West from a variety of different perspectives. The focus will be on the major trends in Western civilization and world history from the 16th Century to the present. At various points different types of influences on history will be important—these will include and are not limited to economics, technology, philosophy, diplomacy, social/cultural trends, religion, science, literature and the arts. In addition, students will be learning about the interaction between the emerging Western powers and other regions of the world. The roots of modern social, political, and economic systems are one ongoing theme. The skills that are sharpened, along with the knowledge that this course develops will enable students to understand and appreciate both the character of historical change and the historical roots of contemporary issues. Learning/Assessment Strategies This course has been designed to provide a systematic approach to the analysis of World History: The West and the World, University Preparation, related to the strands and expectations in the curriculum document The Ontario Curriculum, Grades 11 and 12, Canadian and World Studies. The challenge presented by this course is the sheer breadth of history that is expected to be covered. The course should simultaneously engage student interest and develop their ability to read critically, and process information analytically, to critique primary and secondary sources in print and in audio-visual forms, and to respond thoughtfully to issues in a clear and original manner. Students have to actively discuss, debate and challenge ideas, have an opportunity to record their thoughts, and have a variety of ways to demonstrate their learning. Learning Skills In this course there is a strong emphasis on the development of higher order and critical thinking skills. In addition there will be a lot more reading than most students will expect—this is a University level course and students should be developing the ability to read for meaning and critique written and visual sources. For students to be successful in developing these skills requires the opportunity to learn and practice critical thinking skills, and an opportunity to share and defend the results of their study with their peers. There will be a variety of assessments to ensure students are working on developing these skills. 1 Course Content Units: Titles and Time Unit 1 Foundations and Institutions Challenged (intro, 1490—1715) Unit 2 Revolution and Change (1700—1815) Unit 3 Century of Transitions (1789—1914) Unit 4 Breakdown in International Order (1914—1945) Unit 5 Entering the People’s Century (1943—2000) Unit 6 Independent Study Project Units may not be taught exactly in this order; some units may overlap each other Unit 1 This unit sets the foundations for the inquiries that are germane to the study of the West and the World over a period of almost five hundred years. Students examine several historical underpinnings of the modern world and some of the critical ideas and definitions that have been developed in treating history and social sciences in ‘the West.’ The Renaissance and the Reformation will highlight this look at the 16th and 17th Centuries—times of social challenge including a huge increase in technological developments from approximately 1480--1715. Unit 2 Students explore fundamental changes in Western civilization and their impact on the non-Western world. The 18th Century is viewed here as an age of optimism and progress. The Reformation and Renaissance gave rise to the Enlightenment—a revolution in science, philosophy and politics that we are still experiencing today. Students scrutinize humanity’s relationships with the natural universe, religious values and institutions, and the social, economic, and political order in the era approximately between 1700 and 1815. Unit 3 The 19th Century saw Europe and the World radically transformed. At the time of the Congress of Vienna, all of Europe was governed by monarchies and most of the goods sold were still produced in small shops or out of the homes of artisans. One hundred (largely peaceful) years later, the Industrial Revolution had transformed how and where people worked, radically altered the landscape of Europe, launched massive urbanization, and established class divisions more clearly than ever before. This unit will recap much of the French Revolution (1789) and finish on the cusp of World War 1 (1914). Unit 4 The 20th Century was a century of extremes. Communism, fascism, and democracy were tested worldwide. Precipitated by the West, two World Wars were fought for global domination and the old ‘balance of power’ world of Europe was replaced by a bi-polar world (and the ensuing cold war). Technology, while it increased forms of communication and rapidly advanced scientific discovery, was also applied in a perverse way in the Holocaust. Unit 5 Nuclear weapons forever changed the nature of war and the diplomatic efforts of states would take on a new urgency in the face of the nuclear age. In the new bi-polar world, nothing would ever be the same. Democratic forces would emerge as triumphant in general but other social forces would emerge with new threats to the ‘western’ order. Unit 6 (research component) Each student selects a topic not covered in detail in the course and writes a research essay due one month before the end of the course. This essay based on independent research on a student-selected topic, provides a forum for intellectual activity and the development of critical analysis skills. 2 Achievement Category Weightings. History and Social Sciences: Knowledge/Understanding 25%; Thinking/Inquiry 25%; Communication 25%; Application 25% *This is a course designed around ‘University-bound’ students. There is a lot of ‘theory’ content and abstract thinking required. KU --Knowledge involves key people, events, trends (i.e. trends in intellectual history, diplomatic history etc.) etc. TI --Thinking/Inquiry involves critical thinking, reasoning and thoughtful analysis of historic documents and evidence. C --Communication involves both oral (a major seminar, several question sets) and written (a major essay, reflection pieces) A --Application involves both effective use of research processes as well as analysis of documents and debates in history. 70 % = Course work Evaluation (major assessments) **Throughout the semester the largest single evaluation will be the completion of a seminar presentation. Topics and ‘starter readings’ are posted in the school ‘pick-up folder.’ Choices of topics (with reading overviews) are appended below in the digital version of this outline (pick-up folder). 30 % = Final Exam *Board/School Policies all students are expected to be in class: on time and prepared with binder, paper, and writing materials; with a positive attitude towards participation and cooperative learning; with assignments complete and cared for; all assignments will have a specific due date clearly noted and/or discussed students are expected to submit their assignments by the stipulated deadline. A penalty of (up to) 10% per day will be applied to late submissions. Once an assignment has been returned any outstanding assignments will be assigned a zero grade. PLAGIARIZED WORK WILL BE GIVEN A MARK OF ZERO. Please refer to the student planner for the school’s plagiarism policy (i.e. plagiarism automatically merits a consultation with a vice-principal etc.) Resources Textbook: Legacy: The West and the World Replacement Cost: $80.00 See the course pick-up account for numerous resources, begin by making a digital copy of the extended course outline. also in the ‘pick-up’ you will find: a writing kit (with several practice exercises); a critical thinking kit; a ‘group-work’ outline (solve problems before they start by reading this), along with other ‘skills development’ material. None of these materials are required but they may all prove useful to your current and future academic pursuits—the ‘best study strategy ever’ piece has enjoyed a lot of popularity. 3 Online resources you should ‘bookmark’ (all three) Exemplars_Grade 12_ link http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/curriculum/secondary/canworld12ex/ --Examples of the Ministry of Education’s grading guidelines. These are real student‘s assignments, in various subject areas, each graded by a panel of Ontario teachers. THE BEST online resource for primary documents. Well sorted and thoughtfully selected, everything you would need for basic research in BOTH high school and undergraduate University is right here! Of course you’ll need other (secondary) resources as well. The ‘modern history sourcebook’ is divided into ‘Early Modern Europe,’ ‘Three Revolutions,’ the ‘19th Century,’ and the ‘Modern World’ www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/modsbook.html The ‘Legacy’ textbook online resource guide (sponsored by the publisher of your textbook) Click the ‘continue’ link at: http://www.mcgrawhill.ca/school/booksites/legacy+the+west+and+the+world/student+resources/index.php Unit one resources from this same site are appended below to help get you started. Unit 1: The World Reinvented Chapter 1 Renaissance and Reformation 1480 - 1600 WebMuseum: La Renaissance http://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/glo/renaissance/ From Paris, the WebMuseum provides a superb collection of online Renaissance art, focusing on the Renaissance in Italy, the Netherlands, Germany, and France. This informative site also offers art history of the period and presents the work of numerous painters, including Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Titian, and Michelangelo. Renaissance: What Inspired This Age of Balance and Order? http://www.learner.org/exhibits/renaissance/ The Annenberg/CPB Project invites you to explore the Renaissance at this well-designed site featuring sections entitled Out of the Middle Ages, Exploration and Trade, Printing and Thinking, Symmetry, Shape and Size, and Focus on Florence. This site also has hands-on activities. The Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci http://www.visi.com/~reuteler/leonardo.html A simple and very useful web site displaying an excellent collection of drawings by Leonardo da Vinci, thumbnailed and available for downloading. Chapter 2 The Age of Absolutism 1600 - 1715 4 The European Enlightenment Glossary: Absolutism http://www.wsu.edu:8000/~dee/GLOSSARY/ABSOLUTE.HTM A succinct, well-written history of the concept of absolutism during the European Enlightenment. This work, written by Richard Hooker, is part of the European Enlightenment Glossary. Creating French Culture: Treasures From the Bibliothèque Nationale de France http://lcweb.loc.gov/exhibits/bnf/bnf0001.html This U.S. Library of Congress online exhibition presents many items never before seen outside of France. Especially pertinent to this chapter are the sections called The Path to Royal Absolutism, and The Rise and Fall of the Absolute Monarchy. Includes a spectacular assortment of primary source illustrations. Internet Modern History Sourcebook: Absolutism http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/modsbook05.html Part of the Internet History Sourcebooks Project, this site provides links to a variety of primary source documents pertaining to absolutism, including important works by Thomas Hobbes, Cardinal Richelieu, Jean Domat, and Michel de Montaigne. Chapter 3 Contact and Conflict 1450 - 1715 The Mariners' Museum Age of Exploration Curriculum Guide http://www.mariner.org/educationalad/ageofex/ Based on The Mariners' Museum Age of Exploration Gallery located in Newport News, Virginia, this online curriculum guide offers a wealth of resources for students and teachers. It includes images, video, and text, and users are invited to download these resources for transparencies, presentations, or reports. The site also provides lesson plans, links to related web sites, and guides to other reference materials. Exploration and Settlement: Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage http://www.heritage.nf.ca/exploration/default.html This heritage web site was constructed by Memorial University in Newfoundland. It chronicles European exploration, with an emphasis on European discovery and its impact upon the East Coast of what is now Canada. It includes sections on early exploration, geographical knowledge, navigation methods, and the European migratory fishery. The Exploration and Discovery Home Page http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/gmdhtml/dsxphome.html The Geography and Map Division of the U.S. Library of Congress maintains this web site documenting the discovery and exploration of the Americas. It offers both primary source manuscripts and an impressive collection of digitized reproductions of original historical maps. The Middle Ages http://www.stratford.library.on.ca/kids/subjects/worldhist.htm Find out what happened on any day in history - like your birthday! Find out about the homes, clothing, health, and the farms of the people who lived in the Middle Ages! 5 Seminar topics (not in order of presentation dates) --read the overviews carefully before choosing a topic 1) Darwin (nature’s ‘purpose’?) 2) Deism 3) Liberalism: A new approach to Liberalism (Utilitarianism and its critics) 4) Locke: Using Newton’s method to understand the mind 5) Feminism and Women’s Rights 6) Hegel: German rationalism, Romanticism and the meaning of history 7) Freud’s new world (the triumph of the individual?) 8) Karl Marx: not dead yet (really) 9) The ‘birth’ of Nationalism (and national identities) 10) Romanticism Overviews of seminar topics 1) Darwin (nature’s ‘purpose’?) Outline: Science enjoyed tremendous prestige in the late 1800s. This new ‘faith’ in science, to solve the world’s problems, was no where more obvious than with new science of biology. Ultimately the cultural acclaim of the theories of Charles Darwin would put a final stamp on the importance of biology—possibly to explain the source and purpose of life itself. Darwin’s seminal work (‘Origin…’) was one of the most famously meticulous pieces of science in all of history. It had to be, he was saying something profoundly shocking to his era. His insights would fit into a wider cultural tendency to think about nature and culture inn terms of ‘evolutionary change.’ Darwin’s ideas grew from his own studies of Geology and his interest in Malthusian population theories, as well as his own travels in South America. His views about what would come to be called ‘natural selection’ and ‘survival of the fittest’ were a profound challenge to the enlightenment conception of a harmonious natural world and Christian beliefs about divine meaning (or divine purpose) in the process of nature. Eventually it was his second work (‘Decent’…)—decidedly less scientific but even more controversial—written as a reply to the racism of ‘social Darwinists’ of his time, that would lead to most of the misunderstandings of his theories that we still believe today. From global eugenics movements (in Alberta, for example), to genocide and onward to even modern atheism, Darwin’s has been grossly oversimplified and generally misunderstood. 2) Deism Outline: Beginning as a widespread religious phenomena among the educated classes of Europe, deism relates to a belief in a God whose existence and goodness are proven by nature ,and a disbelief in the Judeo-Christian tradition of belief through revelation (i.e. revealed biblical 6 texts, miracles). Deism also believes that there is a completely natural and general way to understand God’s providence. They believe that God’s sole relationship with his creation is through the natural order of things (nature) and this reflects his will/wishes/plans—this rules out all acts of particular providence, especially miracles and revelation. Historians traditionally distinguish between positive deism (the proof of God and his qualities) and negative deism (critique of claims of religious revelation and special truth). Criticisms range from moral criticisms about trying to interpret God and give ‘him’ human qualities, the social role of priests and religious hierarchies on to criticisms of the veracity of scripture itself. Above all, deists were marked by their common contempt for the Christian clergy, whom they saw as suppressing reason and free thought. This, they argued, was a false separation of mankind from their natural birthright. The struggle between deists and Christian intellectuals was on of the most defining characteristics of (over) a century. 3) Liberalism: A new approach to Liberalism (Utilitarianism and its critics) Outline: This reading looks at another important "ism" that gained intellectual followers in the early 19th century and sought to explain the meaning of the French Revolution. The topic area stresses the new ‘liberal’ philosophy of individual liberty and human rights; it also notes contrasts between Britain's liberal utilitarian movement and the French liberals' quest for a stable, constitutional political system. There is an underlying argument here about what the role of the state should be in providing for individual liberty—there is always going to be a trade off between increasing ‘equality’ or increasing ‘freedom’ and French vs British authors hammer at this argument in different ways. These differences appear in the works of two major thinkers from each camp. Jeremy Bentham and Benjamin Constant, whose lives and ideas are compared here as examples of the contrasting trends in British and French Liberalism(s), are only the ‘tip’ of the debate. It is a debate that still rages today and the shifting of the ‘utilitarian’ ideal from the greatest pleasure for the greatest number to the greatest good for the greatest number then, the greatest freedom for the greatest number underlines the impact of those same French thinkers. 4) Locke: A new way to understand knowledge (or: using Newton’s method to understand the mind) Outline: John Locke is not read today with much attention or enthusiasm but his ideas had an overarching influence on the thinking of people for over a century. It is almost impossible to overestimate the way he changed the culture of the thinking of intellectuals of his time. There is a classic distinction made between Descartes’ ‘rationalist’ view of the world and Locke’s ‘empiricist’ view but this is a VERY oversimplified tendency—both thinkers display elements of each other’s ideas. Locke’s version of empiricism (sensory based) comes out of his view that the origins of all our ideas/knowledge suggests clear implications for designing a society. Where Descartes held that ideas are innate and then will give us truth about the real qualities of the world, Locke holds the belief that all we know is ‘acquired’ so we only have knowledge that comes out of our experiences in the world. Ideas then must arise from ‘sensations’ (our senses) or reflection (the mind’s awareness of its behaviours) –simple sensations combine with simple reflections to create complex ideas. Our knowledge is therefore limited strictly to our experience, we cannot know the real essence of anything. Locke’s ‘epistemology’ will change the nature of the ‘problem’ for over a century—it will take Kant, over a century later, to provide an answer to Locke. For Locke the problem is not to know what the world is—we humans may not be ‘fitted out’ to know this—but to understand how the world behaves. Note: a ‘supplemental’ philosophy oriented reading is included to help clarify this material. 5) Feminism and Women’s Rights 7 Outline: The legacy of the French Revolution included a growing 19th Century debate about how the "Rights of Man" could be extended to women. This seminar involves an examination of the development of early feminism, one of the many new "isms" to emerge in the aftermath of the revolutionary upheavals. You’ll examine contrasting themes in early feminist works and note the ideas of Olympe de Gouges and Mary Wollstonecraft, who proposed that women should be granted all the new social and political rights that modem societies were then granting to men. Other writers, however, sought more opportunities for women to participate in the mostly male world of European cultural life—a theme that appears in the life and books of Germaine de StaeL. Concluding with a look at the continuing (and unsuccessful) campaign for women's rights in the French Revolution of 1848, some discussion of the way these early arguments for women’s participation in public life may or may not have been accepted in modern societies is clearly a starting point. Further investigation of cultural tendencies to distinguish between female (domestic) life and male (public) areas of social life—over several eras—would be helpful. Final investigation of arguments of George Sand and John Stuart Mill (though their approaches differed) as to how the (then) modern conception of ‘human rights’ would not be a reality until such rights were extended to women will finish this topic strongly. 6) Hegel: German rationalism, Romanticism and the meaning of history Outline: German thinkers had developed a wide and rigorous critique of French Enlightenment ideas before there was a French Revolution—indeed they did this long before there was even a (united) German nation. However, these ideas became influential in the decades after the French Revolution. German ‘idealist’ philosophy merged with the new nationalist ideas in the massive collection of German speaking states—formerly making up most of the ‘Holy Roman Empire’—i.e. the first Reich. When the Napoleonic wars spread nationalist ideas across Europe, German writers (i.e. Herder and Fichte) fed on this cultural influence and developed uniquely ‘German’ intellectual traditions. The most influential German philosopher in the decades that followed the French Revolution was Hegel. His ideas had a very complex relationship with the ideas of the Enlightenment, early German romanticism and all other wider Western traditions. A tremendously brilliant and gifted historian, it was Hegel’s philosophy of history that had the most profound impact. Hegel he saw history as a ‘dialectical process’ where a transcendent spirit (or ‘idea’) was seen to be “unfolding” in different societies and in historic eras. His theories encouraged Germans to study history deeply and to understand historic conflicts as having even deeper philosophical significance. His ideas would contribute directly to the establishment of no only a ‘new’ great power nation in Europe (Germany) but a new nation that would completely upset all old relationships between there ‘great powers’ because the newly constituted Germany was immediately the most powerful nation on the continent. 7) Freud’s new world (the triumph of the individual?) Outline: To a considerable extent, the Western intellectual community is still beholden to an essentially Freudian conception of human nature. There is still a major debate among many as to whether or not Freud’s ideas are truly scientific—either in their form or in content—in-as-muchas they can be refuted scientifically. Freudian theory is itself the culmination of the "Victorian era" where science was dynamic, opposing ideas, conflicts, and "conservation." Freud (18561938) was trained in medicine (he’d dissected thousands of eels as a young graduate student) and he was indoctrinated in the very positivistic philosophy of the science of his times. He also took more or less for granted the idea that human mental/psychic processes have roots that extend into the non-human animal world—where survival is the main challenge. 8 Freud's theory of mind suggests unconscious (dialectical) oppositions between the pleasure/pain principle of Darwinian survival and the social/cultural realities we face; those of morality and conformity. For Freud theses opposites are internalized as our conscience. As Freud sees it, in this struggle our ‘conscious self’ is formed and is never really authentic. We are all ‘selves’ that can only understand ourselves through lengthy analysis of our repressed desires—many of which are revealed in our dreams and the symbols to which we find ourselves attracted. 8) Karl Marx: not dead yet (really) Outline: Marx (1818-1883) defended a theory of economic determinism grounded in a more general theory of dialectical materialism. The central thesis is that any society does not actually create itself. It is instead itself a creation of economic forces—based on a given society's forces and modes of production. The state/government arises simply to protect the interests of those who command the productive forces. In capitalism, a class structure evolves in which workers create value by their labour. For Marx, this labour is expropriated (as profit) by the owners of the means of production and this ‘surplus value of labour’ (profit) is accumulated as capital. This capital is itself further used to continue the exploitation of labour. The exploitation of the working class is necessary in the capitalist state. Marx believed the overthrow of a capitalist state can be achieved only by revolutionary means. Ultimately, there follows classless state, following the dissolution of the state (a withering away of the state) as the apparatus of government would no longer be required to fulfill its conventional duties to the capitalist class (bourgeoisie). The workers of the world would have therefore united! (as per the preamble of Marx’s Communist Manifesto) The Marxist critique of society is today more of a subtext than a guiding bible of reform. What survives, apart from lingering ideological loyalties, is the promise of a reliable (bona fide?) social science. Possibly even capable of explaining the how society and social structures determine personal identity and analyzing different (perceived) injustices in modern capitalism. Though often quickly dismissed, Marxism is still very much alive in many critical schools of thought and all areas of the social sciences. 9) The ‘birth’ of Nationalism (and national identities) Outline: The growth of European cities and the expanding power of European nation-states steadily transformed the social importance of local and national writers, philosophers and intellectuals. This reading outlines how intellectuals became increasingly connected to the urban cultural institutions of modern nations, including the new schools/Universities and newspapers. These new institutions fostered nationalism and the national idea (having a country of your own) became a central component of cultural and personal identities for many smaller ethnic/cultural groups all over Europe. The writing of many Intellectuals, often making their arguments on behalf of specific peoples, played a major role in the expansion of nationalism. In the end, this powerful combination of new cultural and political ideas may very well be seen as the most influential "ism" of the entire post 1500 (modern) era. With a new Europe that was being transformed by the liberal and democratic ideas of post-French Revolution and, at the same time, the forces of an emerging new economy (capitalist) alongside the industrial revolution, the forces of change have possibly never been so powerful anywhere nor at any time. In the years immediately following the Congress of Vienna (1815) nationalism and liberalism were linked ideologies that challenged the more ‘reactionary’ and (hopefully) stabilizing plans of the Congress. Revolutionary movements thrived all over Europe—massive revolts against the old regimes in Spain and Poland (1820); 9 nationalist revolts in Greece and Serbia and even the Latin American colonies of Spain were among the most famous. In this piece we’ll look closely at the connections between intellectuals and a few specific nationalist movements. For simplicity we’ll focus on the examples of the French historian Jules Michelet and the Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz, both of whom lived and worked in Paris. 10) Romanticism Outline: The culture of the 19th -century created many responses to the French Revolution and the Enlightenment. These responses extended into the creative arts, literature, and poetry in dramatic ways. The single most influential cultural movement of this period became known as Romanticism, a term that refers to creative movements in a number of different countries and encompasses a wide range of literary and philosophical themes. This seminar examines why historians have increasingly turned to literature to understand 19th-century European ideas— though an examination (in the seminar) of all arts will make the themes clearer. Next, the main themes of Romantic thought are examined, stressing the ways in which it differed from the Enlightenment and gained influence in both philosophy and literature—above all else the romantics refused to se man as anything mechanical, they were horrified at what the industrial revolution had done to working life. It is necessary to recount some differences between German philosophical Romanticism and English literary Romanticism, drawing on the examples of Friedrich Wilhelm Schelling, Germaine de Stael, and Lord Byron to suggest the diversity of Romantic thought. In the end it is the new romantic literary tradition of the ‘hero’ (the romantic hero) that most strongly suggested the meaning of this social criticism of the faith the Enlightenment had in science and progress. These literary characters in popular European novels showed how unconventional and independent artists were deeply concerned with trying to sort out just what it meant to be ‘human’ in a world where science and progress were moving at breakneck speed. The echoes of these ideas are still very much with us today. Writers like Goethe, Rene Chateaubriand and Victor Hugo exemplify the later stages of this criticism even as the ‘romantic hero’ was becoming something of a cliché. The popularity of romantic-era literature, music and visual art led to a rich and complex reexamining of our humanity, a examination that continues today as well. “Those who do not study history are condemned to repeat it.” - Santayana 10