Public Health Data Management at the Local Level

Evolving the Mindset: Public Health Data

Management at the Local Level

2008 - 2009

Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute Fellow(s):

Lisa Swanson; BA

Environmental Health Officer; Black Hawk County Health Department

1407 Independence Ave, 5 th

Floor, Waterloo, Iowa 50703 phone (319) 292-2202 email lswanson@co.black-hawk.ia.us

Mentor(s):

Joy Harris; MPH

Redesign Coordinator; Iowa Department of Public Health

(Acknowledgements):

I am grateful to my team and mentor for encouraging me as we finish the year together. I am also thankful for the expert review and advice from our Systems Thinking coach,

Michael Goodman. I am indebted to have received their support. I value the friendships and connections made through EPHLI. I also want to acknowledge my superiors in

Black Hawk County who have supported me by allowing me to dedicate time and effort for this year of personal and professional growth.

Russell Hadan; MA

Air Quality Officer; Douglas County Health Department

Kristi Campbell; BS

Deputy Administrator ; Section for Disease Control and Environmental Epidemiology,

Division of Community and Public Health, Missouri Department of Health

Michael Goodman; MSME, MS

Principal; Innovation Associates Organizational Learning

2008–2009 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 76

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY:

Technology has advanced to the point where data in almost any format is more easily collected than ever before. Public health practice is no exception to this trend and every program or grant project has data points associated. With no lack of data being collected, management of public health information presents a new challenge. As we amass information about clients, health indicators/risk factors, grant required statistics, data for mandated reporting and internal metrics the challenge emerges. How are we making sense of the data we collect? Ideally, the environmental public health system would be supported by an information plan to ensure that data is managed in a way that it can effectively meet current and future needs.

In the absence of a long term data management plan, existing data is often stand-alone within a program area and fragmented from the “big picture”. This makes it difficult to manage data in a way that it can be easily analyzed, summarized geographically, related to other datasets or integrated into the planning process. When data needs present themselves, ad-hoc solutions only perpetuate the problem.

At the local level, the issue of information management needs to be approached in a proactive way. Foremost, challenge the assumption that there isn’t time to plan for data management. By understanding how data is interrelated (surveillance data vs. outbreak investigations, for example) a procedures/template can be built to ensure that data collection methods no longer perpetuate the fragmented data of the past. A vision must be established amongst all stakeholders in the organization. The mindset of quick fixes to data needs must be evolved so that data management is treated with the same deliberate attention as any other tool invested in.

As environmental public health moves toward major initiatives and public health agency accreditation, it is vital that information management not be a barrier. The more carefully we plan for, anticipate and proactively manage public health data, the more value it can be to the agency.

INTRODUCTION/BACKGROUND:

Agency Introduction:

The Black Hawk County Health Department, a local governmental entity, is the largest local public health agency in the State of Iowa with more than 100 staff personnel providing more than

35 programs and services in areas including Health Promotion, Planning, and Development;

Schools, Clinics, and Outreach; and Enforcement, Surveillance, and Preparedness. The current budget is $4, 841,563, of which, nearly 70% is externally funded from non-property tax sources such as grants and contracts. The Black Hawk Health Department is closely involved with and serves in a leadership role in more than twelve community health coalitions and collaborative partnerships. This is essential to ensure adequate capacity to deliver necessary community health services to our targeted populations.

Under the direction of a five-member governing Board of Health appointed by the Black Hawk

County Board of Supervisors, the Black Hawk County Health Department is a local public health

2008–2009 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 77

agency providing community health services within the State of Iowa. The Black Hawk County

Health Department was established as a full service agency in 1969 under the authority of

Chapter 137 of the Code of Iowa, which states a local Board of Health can “make and enforce such reasonable regulations...provide personal and environmental health services, as may be necessary for the protection and improvement of the public health.”

Agency program areas are organized within the remaining three divisions. See Figure 1 on the next page.

The Health Promotion, Planning, and Development Division employs thirty-four staff members including one Program Manager and one Service Supervisor. Community Health Needs

Assessments; agency fund development; strategic and operational planning; Home Care Aide services; cancer screening and care coordination services; evidence-based health promotion curriculum; and tobacco use prevention activities are facilitated by this division.

The Enforcement, Surveillance, and Preparedness Division has a total of twenty staff members including two Program Managers. Health Officers are responsible for food-borne disease surveillance and State-mandated or municipally contracted environmental health inspection services. Food establishments, hospital and school cafeterias, tanning beds, tattoo parlors, swimming pools, and waste water treatment systems are among sites subject to inspection by staff within this division. Public health preparedness and disease surveillance activities, including Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) clinic operation and case investigation; HIV and

Viral Hepatitis services; Tuberculosis case management; immunization auditing; flu vaccination; and emergency response coordination, are coordinated by a Communicable Disease program tasked with surveillance. Testing, counseling, immunization, and referral of high-risk persons are provided by Disease Prevention Specialists within the division.

The final division, Schools, Outreach, and Clinics , is comprised of a total of fifty-three staff.

The programs associated with Childhood Immunization Services, Immunization Registry

Information System (IRIS) management, Adolescent Immunization Services, and Immunization

Referral and Follow-up Services are administered by this division. School-based Success Street immunization services for children and adolescents are provided through this division.

“The mission of the Black Hawk County Health Department is to promote optimal health policy through education, advocacy and effective regulatory action for the benefit of all citizens within its service area. Through ongoing assessment of public health conditions, the Agency works to protect community residents from disease and disability; and through provider collaboration and service delivery, strives to assure access to appropriate prevention and treatment.”

Black Hawk County Health Department works cooperatively with surrounding Health

Departments to provide regionalized services in a 14 county area in northeast Iowa. The Agency currently operates an annual budget of more than $5 million and works collaboratively with over

15 community health coalitions and partnerships. More than 40 ongoing programs and services are provided by the Agency within its Black Hawk County service area.

2008–2009 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 78

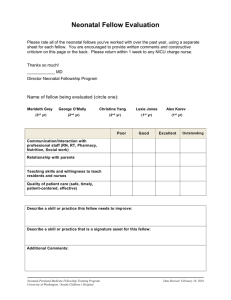

Figure 1.

Organizational Program flow-chart, updated 2007.

Project Background:

In the mid-1980’s Black Hawk County Health

Department purchased their first computer. The first computer was centrally located and available to all staff that wanted to learn how to use it to perform various tasks. In most cases, the preferred method was still either paper-based or typewriter for document output. A few adventurous souls self-taught and managed to create templates for billing and other forms that would have otherwise taken hours of retyping. These little beginnings paved the way for bigger projects and more computer integration into word processing projects. As computers became more common place in the government setting, the use of a computer for organization and efficiency in daily tasks became the norm.

In the years that followed, the Health Department continued to upgrade computer equipment and soon there was a computer at every workstation. Applications such as spreadsheet, database and word processing became necessary tools for collecting and displaying information in a digital

2008–2009 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 79

format. Gradually, inspection records, permit records and other tabular data were transferred from paper format onto computer systems. In the case of Black Hawk County, there were still paper-based datasets in every program area up until the early 1990’s. This meant the translation of handwritten or typed permits, inspections and assessments into spreadsheets and database tables. This conversion opened the door to the ability to query across a dataset for faster and more reliable recall of information that was already entered. In the mid-1990’s the Department implemented a geographic information system (GIS) where tabular data that had a spatial component (address, coordinate, etc) could be mapped out. In more recent years, more and more internet based data collection tools were introduced. These systems have become important for coordination with other agencies as well as State offices, so that data could be collected in collaboration with other stakeholders into one central database in a central hosted location.

Black Hawk County is not unlike other local government agencies. The struggles to embrace new technologies can be a challenge even if there is support. Focus has always been on the efficiencies and improvements to the daily workflow and less on the “bigger picture”. There was never a data management component in any strategic planning.

Every year data is collected to support trend analysis, comparative statistics, GIS analysis, surveillance of health indicators, disparity studies and needs assessments. These more sophisticated uses of data bring to light some of the strains caused by not managing data with any strategic planning. In Black Hawk County, an information technology committee was convened to deal with the hardware needs of the department (physical computers, printers, internet connections, servers, backup options), software needs (database, spreadsheets, word processing, web-based programs) and training needs. While the committee was helpful and continues to be important, the long term needs for data management strategy have never been addressed.

Focusing Questions:

Why don’t we have a system that is responsive and effective for public health information management? Why don’t we have a system in place for management of public health data that can effectively respond to our questions in a timely and flexible manner?

Problem Statement

No system is in place to ensure that public health data is managed to most effectively support the

Department’s functional decision-making and future data.

Key Project Variables:

There are many variables at play when it comes to public health data management: Recognition of need, amount of data generated, number of events that require data management (outbreaks, grants, surveillance), willingness to collaborate, number of decisions that are based on real data, funding opportunities that require measurability, number of programs/efforts that require data sharing and/or data coordination, complexity of generating necessary statistics, security/protection issues with sensitive information, current level of inefficiency, duplication of effort, timelines, ability to update, and ease of accessibility.

2008–2009 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 80

For the sake of consistency in this paper, I will focus on a few key variables that we can study over time:

Demand for data, which seems to be on a pattern of steady increase as time goes on.

Ad-hoc that require response (outbreaks, grants, surveillance efforts)

As ad-hoc response continues, the amount of fragmented data (silos of data in each program area) increases

As we increase the amount of data collected over time, the amount of complexity in the system increases (time/effort required for change) especially as fragmentation continues to rise.

Behavior Over Time:

As we can see in Figure 2, this problem is not on a course to self-correct. Over the course of time, demand for access to the kinds and quantities of data necessary to answer questions to support decision making and measure outcomes is increasing. This increase in need for accessible data is a phenomenon that is not only internal (statistics, trend identification, resource tracking, determination of effectiveness) but also external (indicators required for the State

Health Department, grant related datasets, reportable instances of disease and health hazard). As data-intensive projects and events fluctuate over time, the after-effects of the quick-fix (ad-hoc silos of data) will increase and drop off but with an overall increase. As a result, we have a greater degree of data fragmentation, which increases the effort it would take to correct the problem. The more we neglect to address the issues of data management, we move farther away from a flexible and accessible data system. If we continue to react to data needs in ways that further exacerbate this trend, it becomes harder and harder to bring the information back together at a later point.

Figure 2: Graphical estimation of the behavior of project variables over time

2008–2009 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 81

Figure 3: Shifting the Burden causal loop

Underlying System Theory – Causal Loop Explained

The problem is best described in terms of the Shifting the Burden archetype. The central driving force is the pressure for accessible and meaningful analysis of collected information. Taking a look at the top loop, which is the “business as usual” response to data needs, reflects an attitude that we need a quick solution. Lacking a strategic plan for health data management has meant that each information need was addressed as an isolated dataset. The result (whether it is immediately clear or not) is that we end up with stand-alone data sets that may be significantly less useful or a duplicated effort. As we continue to add these ad-hoc solutions, we have satisfied the apparent urgency for a speedy way to collect and report information but in fact, we have unintentionally increased the complexity of the system. So while we are doing the right thing by using the available technology to add ease of data manipulation, the lack of a plan has some unintended effects on the overall functionality of the data management system. Sooner or later, this unintended outcome is felt, and the difficulty to correct at that point is a barrier to being able to fully use the data we have collected in terms of how it relates to other data collected, other environmental hazards and indicators. Once this sometimes overwhelming

2008–2009 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 82

conclusion is reached, we are then further away from implementing a data management plan than we ever were.

Taking a few steps back, we can explore the bottom loop. In this alternative response to the need for data inputs to decision-making, there is a delay of implementation. This does not need to be a significant delay, so long as the planning is appropriate for the dataset in question. The delay is needed (more so in the initial phases of this more deliberate approach) for examining how each dataset fits into the bigger system picture, how it relates with other datasets, and future needs concerning the dataset. If we can get past the perception that the changes to the process are too overwhelming or that we don’t have time at the beginning of a project (or in the planning phase of a project) to think about data management, improvements can be made. Once there is a commitment and a willingness to consider data management as an important part of the planning process, we can ensure that time spent collecting data will be balanced out with usability and value added to the system.

To clarify the system theory, I will go through the archetype using a well water testing example.

Regular water testing takes place at private wells in our region. The site evaluation details

(environmental descriptors at the time of visit), well construction details (age, depth, type of construction) and water test results are logged by address into a custom in-house database. The custom database enables records to be exported and queried in tabular format. The in-house system also prints out letters to the homeowner relaying the results of their water test and instructions if there are any issues that need attention. The records in this format are loosely tied to other datasets maintained in other formats. The address locations are brought into this database from a central master list of valid address points maintained by the County Auditor.

The water testing records are then loosely tied to a Geographic Information System for postanalysis by address. The same information about the site visit is logged in a web-based state database to satisfy grant requirements. By this description, the data management scheme has some very practical functionality and potential for expanded use.

In the case of the summer flooding, we found out quickly that the inflexibility of a fragmented system was a problem. Iowa found itself in the middle of the worst flooding since the early

1900’s. When flood waters surpassed the “500 year flood” levels and 40,000 people were displaced, private water wells were just one of many public health concerns 1 .

There was an immediate need to mobilize to monitor water quality for residences that have private water wells.

Priority for water quality was making testing available as electricity was restored, helping to supply sanitization information and collecting location/contact logs of affected areas. Because the water was higher than ever before, the affected area was extensive and due to the severity of the flooding, there was a longer than normal time required before residents could re-enter their homes.

Water Testing Example: Quick Fix Response, Business as Usual

Networked log created for calls, water test requests - no address id link, no duplicated record control, lag time with some officers entering log information late which resulted in chaotic scheduling for water testing

Inspections and well evaluations conducted, inspection sheets entered into in-house database by valid address

2008–2009 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 83

Limited ability to accurately determine if an address was directly affected by the flooding, difficulty in separating between flood-affected and lower priority water test requests.

Because water test kits were in great demand, we did have to start to ration the tests and should have had a better system for making sure that available test kits were used on truly affected residences.

Some test kits were directly mailed to the laboratory in Iowa City, who sent the results directly back to the residency, which cut the health department out of the loop and made follow-up impossible. Also, in the cases where the home owner was displaced, the results were sometimes not ever received (if the results were sent to the house that had been flooded and wasn’t livable). This aspect of the water testing results had a drastic effect on our ability to look at overall private water impact by the flooding and any follow-up query regarding severity of contamination, number of times the sanitation process was used and even just the ability to speak with the homeowner to address any issues of water quality as a direct result of the flooding event.

Had time been invested during the flood response planning sessions for how we could best handle the data aspect of our environmental health efforts, we might have done things very differently. Because a flood event is highly location specific, the basis for each log should have been a valid address. The phone log and water test request lists should have been all crossreferenced back to a valid address so it could be supplied with known affected areas (from the geographic information system by spatially querying the affected areas and exporting the addresses). If the phone log and water testing log were relationally linked based on address, keeping track of duplicate testing requests and progress with testing affected wells would have been a much more streamlined process. So the better approach to this data management need would have been to take a step back to figure out a way to incorporate the new event into the existing system instead of introducing stand-alone solutions for each aspect of our response.

Because we did the easier/quicker solution by creating separate trackers, we actually made it harder to look at the event as a whole and failed to use the technology as effectively as possible by implementing appropriately.

How can we conquer the habit of taking the path of least resistance?

Breaking out of “Business as Usual”

Because it is inherently easier to leave things the way they are, there are certain factors to overcome so that there can be unity behind the vision of change in the system. Arguments against change are based on the fears that transition/planning takes time, commitment and willingness to step back and think long-term for data management decision making. At the same time, there is a tendency to convince oneself that the current system is not so bad (denial or ignorance to the backfire). Efforts to gain commitment to a change will require a general shift to long term planning where data management is concerned and a demonstration of efficiencies and added value to the system. The current mindset and/or lack of awareness of the inadequacies and consequences of the short term solutions to data management must be brought to the attention of the stakeholders. Only when there is awareness and support for the needed planning can there be change. If properly communicated, the benefits of eliminating the unintended backfires (which are directly related to “business as usual”) will be a motivating factor for change.

2008–2009 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 84

10 Essential Environmental Health Services:

As we look at the beneficial impacts of effective data management in the environmental public health workflow, it is natural to study in terms of the essential services

2

. Because data is so integral to program planning, implementation, tracking and outcome measurability, it is reasonable to expect that a strategy aimed at improving the management of data can improve capacity to deliver these core functions.

The following section discusses each of the essential services, separated into core function area:

ASSESSMENT

• Monitor health status to identify community

The ability to compare, trend, aggregate and analyze data in our field is a very important health problems

• Diagnose and investigate health problems and health hazards in the community way to get valuable insight into the work we do. All of the data we collect should be deliberate and in line with specific, meaningful goals. When this is accomplished, the data is more valuable to us and is a vehicle for answering questions and helping to truly monitor health indicators and understand the true status of the community.

2008–2009 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 85

POLICY DEVELOPMENT

• Inform, educate, and empower people about health issues

• Mobilize community partnerships to identify and solve health problems

• Develop policies and plans that support individual and community health efforts

• Enforce laws and regulations that protect health and ensure safety

• Link people to needed personal health services and ensure the provision of health care when otherwise unavailable

ASSURANCE

• Ensure a competent public health and personal health care workforce

• Evaluate effectiveness, accessibility, and quality of personal and population-based health services

• Research for new insights and innovative solutions to problems

Data is a fundamental basis for understanding health status in our community, an important part of being able to effectively match policies to target populations, study the effectiveness of policies and program efforts.

Closely monitoring how data is managed will ensure that we will be able to take a more intelligent, informed look at services and outcomes with the flexibility to adapt the system to meet evaluation needs.

When a strategy is in place for effective data management, it is possible to gain a greater insight into how indicators and program information (and the “real world” indices that the data describes) relate to other datasets and how they change over time. This flexibility means that we will have a more accurate way to evaluate program effectiveness (Are we getting the expected outcome? Can we measure progress and success as a direct result of our use of resources?). Data is the backbone of being able to support evidence-based environmental health programs.

State of Iowa Goals Supported

In The Future of Public Health , the Institute of Medicine (IOM) charges all public health agencies to regularly and systematically collect, assemble, analyze and make available information on the health of the community, including statistics on health status, community health needs, and epidemiologic and other studies of health problems.

3

In a more recent IOM report, focus on population health and assessing the multiple determinants of health was again emphasized.

4 As a result of these national recommendations, the Iowa Department of Public

Health (IDPH) developed a comprehensive reporting tool to assist communities across Iowa with communicating their community health needs and planning initiatives. This assessment process a public health initiative that enables communities across Iowa to assure the health of their citizens through the development of a comprehensive report on leading health indicators, health priorities and health improvement plans.

2008–2009 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 86

The success of the CHNA & HIP initiative depends on an organized assessment and planning process. The CHNA & HIP process has three modules:

1.

Community Contacts - This module is the directory of the local public health leadership and community partners who contribute to the CHNA & HIP process.

2.

Leading Health Indicators - This module is the repository for health and related data specific to the county. This data-driven profile will be reviewed by the community contacts to determine community health priorities.

3.

Health Improvement Plans - This module is the blueprint for addressing community health priorities through structured health improvement plans.

The coordinated effort and standardized reporting tool of this process establishes a solid framework for all of Iowa to better carry out the first and most significant core function of public health: Assessment. Consistent, comprehensive reports for all of Iowa will allow for a solid profile of the health needs of the state and local communities. The plans submitted provide guidance on resource needs to successfully address health priorities. Appropriate allocation of resources and consistent planning efforts help ensure successful implementation of all core functions of public health. Any improvements made in data management of public health information at the local level will only help the system to better support this process.

National Goals Supported

CDC Health Protection Goals

In the 2007 document, Health Protection Goals and Objectives

5 , the goal to “be prepared for emerging health threats” overarches the following objectives:

Integrate and enhance the existing surveillance systems at the local, state, national, and international levels to detect, monitor, report, and evaluate public health threats.

Support and strengthen human and technological epidemiologic resources to prevent, investigate, mitigate, and control current, emerging, and new public health threats and to conduct research and development that lead to interventions for such threats.

Enhance and sustain nationwide and international laboratory capacity to gather, ship, screen, and test samples for public health threats and to conduct research and development that lead to interventions for such threats.

Assure an integrated, sustainable, nationwide response and recovery capacity to limit morbidity and mortality from public health threats.

Expand and strengthen integrated, sustained, national foundational and surge capacities capable of reaching all individuals with effective assistance to address public health threats.

It is arguable that the basis for evaluating the effectiveness of any intervention is our ability to monitor health status through public health information. Efforts to improve the management of public health data can indirectly benefit each of the health protection goals in the sense of evaluating and assessment. In the case of the above mentioned objectives, the ability to study health status requires the ability to monitor and understand health status in measureable ways.

Appropriate data management enables us look at environmental health as a system and provides a means to consistently measure effectiveness.

2008–2009 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 87

National Strategy to Revitalize Environmental Public Health Services

The objectives highlighted in the CDC’s “National Strategy to Revitalize Environmental Public

Health Services” include the aspect of supporting research. The intent is that public health services can be improved with the identification of emerging needs, identification of antecedents of disease outbreaks, defining interventions and evaluating the impact of decisions on environmental practice (goal II) 6 .

Environmental Health Competency Project

The aim of the project is to “provide broadly accepted guidelines and recommendations to local public health leaders on the core non-technical competencies needed by local environmental health practitioners working in local health departments (LHDs), to strengthen their capacities to anticipate, recognize, and respond to environmental health challenges”.

7

As such, the recommendations include several areas that are directly aided and supported by appropriate data management:

Data Analysis and Interpretation: The capacity to analyze data, recognize meaningful test results, interpret results, and present the results in a meaningful way to different types of audiences.

Evaluation: The capacity to evaluate the effectiveness or performance of procedures, interventions, and programs.

Managing Work: The capacity to plan, implement, and maintain fiscally responsible programs/projects using appropriate skills, and prioritize projects across the employee's entire workload.

Computer/Information Technology (IT): The capacity to utilize information technology as needed to produce work products.

Reporting, Documentation, and Record-Keeping: The capacity to produce reports to document actions, keep records, and inform appropriate parties.

Communication: The capacity to effectively communicate risk and exchange information with colleagues, other practitioners, clients, policy-makers, interest groups, media, and the public through public speaking, print and electronic media, and interpersonal relations.

The emphasis on these competencies makes it clear that it is important that we have at least a basic ability to manipulate and manage data pertaining to environmental health. Whether the purpose of the dataset is to help understand or allocate resources, to study a target population, to communicate effectively or in interpreting an outcome, as an agency, we have a responsibility to be stewards of our supporting data so that we can build capacity and be as effective as possible.

2008–2009 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 88

Figure 5: Project Logic Model

2008–2009 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 89

PROJECT OBJECTIVES/DESCRIPTION/DELIVERABLES:

Program Goal

A public health information plan needs to be in place to ensure that data is managed in a way that it is accessible, protected, scalable and adaptable to meet current and future needs of the Department.

Health Problem

Data is only valuable when it can be used. Without taking action to manage public health information, we are limited on the amount of value we can get back from our tracking and recording efforts.

Outcome Objective

By 2010, data management considerations reflect an acknowledgement of the importance of considering data management in public health programming and strategic planning.

Tools for data management will be deliberately designed to be in line with the strategic goals of the Department.

Determinant

The pivot point for the success of this project lies in willingness to abandon the old mindset and adopt a proactive approach to data management.

Impact Objective

By 2010 we will have an established process for ensuring that environmental public health data is managed in a flexible and accessible manor such that we can support decision making, needs assessment and

Contributing Factors

If our current reality is the proverbial “point A”, then the “point B” where we want to be for the purpose of agency accreditation, that tension is a motivating factor.

Reporting that is not currently possible or that needs to be a reality by a set date; for example the 2010 phase of our Community Health Needs Assessment. Many indicators need to be collected over time need to be part of the strategic data management plans as soon as possible.

Lack of awareness regarding the limitations of business as usual

Lack of set policies and inclusion of data management in the planning process

Process Objectives

Managers and grant administrators will be taking an active role in the determination of how information for their program relates to the Departmental goals/objectives

2008–2009 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 90

A Department-wide inventory of current/existing datasets will give insight into the information already collected, gaps in necessary indicators being collected and the relationship between the two.

Steps are taken to ensure that we can more quickly adapt our data collection in ways that will still fit into the data management system. Templates to enable the quick set up of data collection tools that are already integrated with core datasets.

Value added to efforts in digital information storage because of expanded ability to access the data in a system

METHODOLOGY:

The following methodology describes the steps involved to accomplish the goal(s) of this project. Acknowledging that Black Hawk County is not so very unlike other local health departments (taking into consideration jurisdiction size and stage of technological advancement), the following activities/outcomes could be replicated anywhere there was a willingness to support this sort of shift in approach to data management.

Key Resources

Human capital: technical expertise, trained staff

Commitment to investment of time for development, implementation and expansion

Technology: hardware/software to support, network ability

Partnerships

Key Stakeholders

Health Department Director

Division and Program managers

Board of Health

Partnering agencies

Grant administrator(s)

Outbreak investigators

Management Information Systems (MIS) committee

Event: Stakeholder Involvement

Activities: The Management Information Systems (MIS) committee needs to be instrumental in helping to guide this shift in mindset. The committee is an already established body of invested persons in the Department, made up of responsible representatives from each of the 3 divisions (see Figure 1) charged with panel discussions of information technology issues Department wide. This body is positioned to put into place recommendations to enforce the proactive approach to data management and oversee that strategic planning has an information component in every program area.

2008–2009 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 91

Event: Inventory of Current Datasets

Activities: Black Hawk County Health Department is currently in the process of completing a comprehensive dataset inventory. When complete, this inventory will serve as a basis for evaluation of existing systems to ensure that opportunities for efficiencies are being taken. Relationships between previously unrelated datasets can provide new insight for program evaluation, determination if we are getting desired outcomes, health indicator tracking and target population identification.

Activities: As programs evaluate if it is determined that some of the data currently collected is not being used for planning, steps need to be taken to determine what indicators should be tracked in addition or instead.

Event: Alignment with Future Data Needs

Activities: As we move toward major initiatives, our ability to provide specific indicators of success and demonstration of agency need will require that we have been diligent to collect and maintain key datasets. We are at a crossroads now for preparing to be able to answer those questions and ensure that we are positioned to grow with the demand for useful and accessible information.

Community Health Needs Assessment and Health Improvement Plan (CHNA

& HIP): 2010 is the next evaluation year for the Black Hawk County Health

Department. This is a revisit to detailed evaluation of our services done in

2005. The 2007 mid-year report was completed and submitted.

National Goals - Healthy People 2010

8

Accreditation: The demand for proof of program effectiveness and agency accountability will drive how we collect and report information. Indicators tracked over time provide a basis for program quality improvement, selfassessment on service delivery and capacity building.

Event: Development of Templates

Activities: Proactive development of forms that are already planned for and integrated into currently maintained datasets will assure that reduce the amount of adhoc data collection and unintentional silos of information that have proven to be a barrier for effective use of data in the past.

Example: outbreak investigation templates that tie in with inspection programs and contact forms, ensuring that data collected in the heat of an investigation can be reported in terms of code violations and status of a contact.

Example: data collection protocol dictates that site evaluations, water test results, response activities and other indicators make use of common identifiers such as valid address, parcel number or standardized state identification number.

2008–2009 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 92

NEXT STEPS/EXPECTED OUTCOMES:

1.

Complete and continue to maintain the dataset inventory.

2.

Explore new solutions for integrating various database systems together; examine available resources for further expansions such as using Business Objects to tie datasets together for more intelligent and complicated query options.

3.

Continuous involvement of stakeholders in data management. The need for integration into strategic planning is not going to go away. Over time, it should become a natural consideration in project development and program evaluation.

4.

We will test the resolve and commitment of the agency to consider environmental public health data management issues as a very important aspect of all projects, initiatives and assessments. The first big outbreak, special project or new grant will be our chance to prove that the mind-set has indeed changed from the old

“quick fix” response to a process of deliberate strategy with an eye for the future.

2008–2009 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 93

LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITIES:

Lisa Swanson

The opportunity to participate in the Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute has meant a year of personal and professional growth. The insight provided by the assessments and self-evaluation has helped me to find areas for improvement or underdevelopment. It has been invaluable to have access in such a personal way to the wealth of expertise from our guest speakers, who are well respected experts in their fields. It has been a pleasure to get to know them and even receive input on our projects.

Having a personal development coach, the support of my wonderful team and the guidance of our mentor has enhanced the experience. Colleagues met through EPHLI are going to be friends and resources well beyond the course of our fellowship. I am grateful to have been selected for Cohort IV. Above all, I look forward to years of continued personal and professional development as a leader in public health.

ABOUT THE EPHLI FELLOW

Lisa Swanson is a Public Health Officer at the Black Hawk County Health Department.

She works out of the Environmental Health program of the Enforcement, Surveillance &

Preparedness Division. Lisa's training includes GIS Certification, a BA in Computer

Information Systems from the University Of Northern Iowa and a Public Health

Certification from the University of Iowa. Lisa has been a health officer since 2001, primarily dealing with data management, database development, technical support and

Geographic Information Systems for the Health Department. Professional involvement includes the Iowa Geographic Information Council and the Iowa Environmental Health

Association. She serves on several committees relating to Public Health, Environmental

Health and GIS.

2008–2009 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 94

REFERENCES

1.

Swails, T and Carolyn Wettstone. Un-Natural Disasters, Iowa’s EF5 Tornado and the Historic Floods of 2008. (2008) Sweetgrass Books,Inc.

2.

Osaki, C. Northwest Center for Public Health Practice. 10 Essential

Environmental Health Services.

3.

Institute of Medicine. The future of public health. Washington, DC: National

Academy of Sciences Press, 1988.

4.

Institute of Medicine. The Future of the Public’s Health in the 21st Century.

Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences Press, 2002.

5.

US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention. Health Protection Goals. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/about/goals/default.htm

Accessed January 3 rd

, 2009.

6.

US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention. National Strategy to Revitalize Environmental Public Health

Services. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nceh/ehs/Docs/nationalstrategy2003.pdf

Accessed January

3 rd

, 2009.

7.

US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention. National Center for Environmental Health and American Public

Health Association. Environmental Competency Project. Available at http://www.apha.org/programs/standards/healthcompproject/corenontechnicalcom petencies.htm

Accessed January 3 rd

, 2009.

8.

US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and

Human Services. Healthy People 2010. Available http://healthypeople.gov/

Accessed January 3 rd

, 2009.

2008–2009 Fellow Project National Environmental Public Health Leadership Institute 95