Manual For Interpreting in Medical Setting

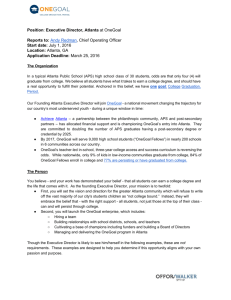

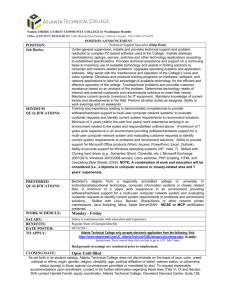

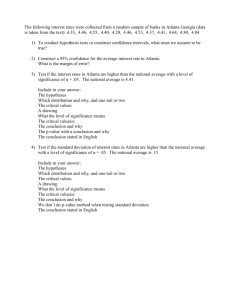

advertisement