Trespass to Chattels sample

advertisement

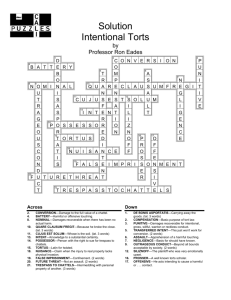

MEMORANDUM TO: Karin Mika FROM: 1513 DATE: September 24, 2003 RE: Applicability of trespass to chattels to unsanctioned mass emailings ISSUE WHETHER A STATE UNIVERSITY HAS A CAUSE OF ACTION FOR TRESPASS TO CHATTELS TO STOP STUDENTS FROM POSTING TO THE UNIVERSITY'S MASS MAILING EMAIL ADDRESS WHERE THE STUDENTS POST QUESTIONABLE MATERIAL AFTER DISCOVERING A GLITCH IN THE SYSTEM. STATEMENT OF FACTS In early August, 2003, Valencia State University (VSU), the potential plaintiff, realized that VSU students Joan and John Smith, the potential defendants, had discovered a way to use the university's "mass mailing" email address to send messages. The Smiths do not tamper with the computer system in any way, but make unauthorized use of a glitch to gain access to the email address. There are no other students who know how to access the "mass mailing" address and the university's computer technicians are attempting to fix the problem, thus far unsuccessfully. Each message sent from the "mass mailing" address goes to everyone at the university, including students and faculty at the graduate level (about 21,000 people). The Smiths, who are twins, have sent at least twenty emails thus far, and continue to do so despite VSU's request for them to stop. The subjects of their messages have included VSU's admissions’ policy, the cost of tuition, the locale of the bookstore, and commentary on certain professors and administrators. 1 Although the storage space of the university's computers is not affected by the messages the Smiths send, the university maintains that the emails cause problems. Graduate students, who are not concerned with the undergraduate issues about which the Smiths write, are insisting that their Deans do something about the mass mailings. Many have threatened to transfer out of VSU. Computer technicians and administrators are spending extra time and resources attempting to fix the glitch in the system and dealing with the fallout from the mass mailings. Students and faculty are annoyed by the "spam" and claim that important messages have been lost because of it. Filtering the messages is not an effective remedy because the university sends out important legitimate mass mailings. Finally, the professors and administrators named in the Smiths' emails are angry and humiliated. Some of their classes have dwindled to prohibitively small numbers, while professors who were not named in the messages are over-enrolled. VSU is considering suing Joan and John Smith for trespass to chattels in order to stop them from sending messages. DISCUSSION Trespass to chattels is a common law tort that occurs when: (1) (2) (3) (4) a person takes the personal property of another or, harms the condition, quality or value of that property or, prevents the owner from using that property for a substantial time period or, physically harms the property or the owner's legally protected rights to the property. Compuserve v. Cyber Prods. Inc., 962 F. Supp. 1015, 1017 (S.D. Ohio 1997). The wrongful interference with personal property that characterizes trespass to chattels is not strictly limited to physical damage, but must include actual harm to property in some form, or deprivation of use. Omnibus Int'l Inc. v. AT&T, Inc., 111 S.W.3d 818, 820 (Tex. App. 2003). Thus, in order to succeed, VSU must prove that, although the Smith twins' mass mailings cause no physical 2 damage to the university's computer system and deprive no one of its use, they are nonetheless liable for trespass to chattels because their emails damage the computer system's value. Although it appears evident that the mass mailings have been detrimental to the university, the damages to the computer system itself are of a predominantly intangible nature. With this in mind, it will be difficult for VSU to prevail using a trespass to chattels theory. There are several relevant trespass to chattels cases to consider. In a recent case, Intel Corp. v. Hamidi, 71 P.3d 296, 298 (Cal. 2003), the court held that the plaintiff could not recover for consequential injuries (e.g., damage to economic relations and reputation) using a trespass to chattels theory. In Intel, the defendant, an ex-employee, used the company computer system to send mass emails critical of the company's employment practices to employees. Id. at 297. The company asked the defendant to stop sending the emails and he refused, although he offered to take anyone who did not want to receive his messages off of the distribution list and did so. Id. at 298. Despite attempts to thwart him, the defendant was able to continue his emailings without tampering with the company's computer system in any way, doing any physical damage, or disrupting the functioning of the system. Id. In holding for the defendant, the court reasoned that his emails did not interfere with the use, possession or legally protected interest of the computer system itself. Id. The court further reasoned that, although the company may have suffered damages due to the content of the messages, trespass to chattels did not cover damages from emails unless they in some way harmed the personal property, i.e., the computer system, itself. Id. In another case, Omnibus Int'1 v. AT & T, the appellate court refused to uphold a summary judgment on the basis of trespass to chattels when a company (AT & T) sent unsolicited advertisements via fax machine to the plaintiff. 111 S.W.3d at 819. In this case, the 3 damages alleged by the plaintiff included the consequent costs for replacement paper and toner. Id. In finding for the defendant, the court reasoned that, because no actual damage to the fax machine or deprivation in terms of use was sustained by the plaintiff, the tort of trespass to chattels did not lie. Id. Based on the general rules concerning trespass to chattels, it seems unlikely that the university will succeed. In order for a trespass to chattels action to be successful there must be a showing of tangible damage. Omnibus, 111 S.W.3d at 820. In both Intel and Omnibus, the courts stated that damages that do not affect the nature or character of the personal property itself are not tangible and thus will not support a claim of trespass to chattels. See, e.g., 71 P.3d at 298. The Intel case is particularly persuasive precedent because the facts of the case so closely resemble the Valencia U./Smith situation and it is the most recent decision on the topic. Like the defendant Hamidi in Intel, the Smith twins have not physically damaged the university computer system, their messages have not been so numerous as to overwhelm the storage capacity of the system, and neither computer network is directly linked to the economic viability of its institution. It should be argued that the court's reasoning in Intel is applicable to the situation at hand. Despite intangible damages that the Smiths' emails may cause the university, the nature of the harm does not constitute damage to the quality, condition, or value of the computer system nor physically harm the system itself. The Omnibus case adds some persuasive currency to this line of reasoning in that it applies it to a different technology, fax machines, and reaches the same conclusion. 111 S.W.3d at 820. In response to this reasoning, the university could argue that Intel specifically is distinguishable in at least a couple of ways. First, the defendant in Intel offered to and did take anyone who did not want to receive his messages off of his distribution list. 71 P.3d at 298. The 4 Smiths have never made such an offer. Many of the alleged damages that are central to the university's objections to the Smiths' emails could be eliminated if the Smiths had made such an offer. For example, problems due to professors' difficulty in making sure they sort out the important emails and graduate students' disinterest in the Smith emails' subject matter would be almost eliminated. Perhaps more importantly, unlike in our case, none of the facts in the Intel case indicate that the defendant’s emails directly affected the success of the company. Id. The facts do not suggest that any employees even threatened to leave the company because of the emails; they were basically tangential to the functioning of the organization. The damages detailed in the Omnibus are also distinguishable. Whereas the damages in Omnibus were limited to the toner and paper used for seven or eight faxes, 111 S.W.3d at 820, here, the university presents information suggesting that the seamless functioning of their mass emailing computer system is central to the functioning of the university as a whole. For example, students are threatening to withdraw because of the Smiths' emails, and enrollment in certain classes has been significantly effected. Therefore, it should be argued that, if the university is so affected and the computer system is central to the functioning of the university, then the damages to the university as a result of the emails should constitute damage to the value of the computer system itself. See Intel, 71 P.3d at 12. There are, with respect to storage situations, at least two cases in which trespass to chattels was found to be applicable. The court in Compuserve Inc. v. Cyber Promotions Inc. held that trespass to chattels lies when a deluge of bulk email messages from a company clogs up storage space and thus damages the ability of the plaintiff company to provide service to their subscribers. 962 F. Supp. at 1022. In this case, the Compuserve computer system stored emails 5 sent to subscriber accounts so that users could access their messages freely. Id. at 1018. Defendants sent out bulk emails that slowed service and resulted in threats by subscribers to terminate service. Id. at 1023. Compuserve attempted to prevent the defendants from sending emails and asked them not to, but they deliberately evaded detection by concealing their identity as the sender. Id. at 1017. The court reasoned that the significant loss of storage space in Compuserve's computer system harmed the system's ability to serve subscribers. Id. at 1022. The court further reasoned that the negative effect of the defendant's "spam" emails on subscriber's use of the system damaged the quality of service their computer system could provide. For these reasons, the court found trespass to chattels applicable. Id. In America Online Inc. v. IMS, 24 F. Supp. 2d. 548, 549 (E.D. Va. 1998), the court held that the defendant, a bulk emailer, was liable for trespass to chattels against the plaintiff's computer network. In AOL, the defendant sent sixty million unauthorized email advertising messages to the plaintiff's subscribing customers after being notified in writing not to do so. Id. at 549. The defendants concealed their identity in the messages and avoided attempts to block them. AOL alleged that their equipment was burdened by the flood of messages from the defendant, their technical resources and staff members were stressed to defend their system from the defendant's bulk emails, and the goodwill of their subscribers was damaged to the tune of 50,000 complaints. Id. The court reasoned that the actions of the defendant met elements of trespass to chattels. The court concluded that the bulk emails flooding the storage space of AOL's computer system constituted an interference with the system. Id. at 550. The court also concluded that the consequent diminished value of the network to subscribers represented damage to the company's property sufficient for a trespass to chattels action. Id. 6 Despite the fact that there have been cases finding that intangible damages may be actionable, these cases appear to be distinguishable and may prove problematic for the university. Specifically, in both Compuserve and AOL, the court applied trespass to chattels largely because the plaintiffs convinced the court that the damages they sustained were actually sustained by their computer systems. See, e.g., 24 F. Supp 2d at 549. In contrast, the facts at hand indicate that the Valencia University computer system has not been flooded or overburdened by the Smiths' emails and thus the specific property in question has not been harmed in the same way. Furthermore, in Compuserve and AOL, the court recognized that the efficiency of the plaintiff's computer system was directly linked to the economic well-being of the company. Id. The courts concluded that, because the computer system is the product offered by the company, anything that makes it less attractive to a subscriber diminishes its value. See 962 F. Supp. at 1022; 24 F. Supp. 2d at 550. The VSU situation is not quite the same. VSU encompasses a broader objective than providing a computer system. In fact, it is safe to assume that students do not pay for the computer system in time increments or choose it for its efficiency. Although they may be said to pay for it proximately with their tuition, its quality likely not as fundamentally linked to the success or failure of the institution. Thus, it is easy to see why a court might decide that the damages in Compuserve and AOL are to the computer system itself while the damages sustained by VSU are merely consequential. VSU may argue that a precedent exists for using trespass to chattels to prevent interference with open computer systems. 24 F. Supp. 2d at 548; 962 F. Supp. at 1015. Although the facts indicate that VSU's computer system is not currently overburdened by the Smiths' mass mailings, they also indicate that there is a potential that imitators of the Smiths might begin to surface and eventually threaten to flood the system. 7 Such an eventuality could arguably constitute damages to the computer system itself, as trespass to chattels requires. 962 F. Supp. at 1015. There are other arguments that may be made by the university. With respect to the related argument that the damages in Compuserve and AOL are more specifically and definitely linked to the computer system itself, VSU should point out the tenuous nature of distinguishing damage to property and consequential damage in determining whether trespass to chattels will lie. 962 F. Supp. at 1022, 24 F. Supp. at 2d. at 550. That is, the value of a particular component of a business or institution like an internet service provider (Compuserve and AOL) or a university is extremely difficult to define without taking many variables into account. For example, the presence or absence of "spam" may have a very limited effect on subscription to a certain Internet Service Provider compared to the other features that make the product attractive, such as in a University setting. In both cases, it seems most likely a court would look at the product as a whole and analyze whether damage is to the property that is the product generally. In conjunction with this, the Smiths could argue that trespass to chattels is clearly defined as limited to damage done to the specific property in question, in this situation the university itself as opposed to a service provided by the university. 71 P.3d at 12. Based on the current interpretations of what is “damage” in electronic trespass to chattels situations, it seems as though this may be the more successful argument. CONCLUSION The general rule for trespass to chattels was established by the common law and refined with respect to the internet and technology. It is, that a person who harms the personal property of another by decreasing its quality, condition or value, causing it to be unavailable for an 8 extended period of time, or preventing its use or a legally protected right to it will be liable. 962 F. Supp. at 1015. The court has established that consequential damages not directly related to the personal property will not lie for trespass to chattels. Id. In this situation, the Smith twins are likely to rely on the enforcement of this general rule to say that the damages suffered by the university are consequential only, and not directly related to the functionality of the entire university. The university may argue that trespass to chattels should be extended to their situation, in which they have been damaged to a degree as a result of the exploitation of their computer system. With these two positions in mind, in seems more likely that although other actions may apply to this situation, trespass to chattels does not. 71 P.3d at 5. The damage does not appear to be tangible enough as contemplated by the courts. 9