"Trespass to Chattels" Finds New Life In Battle

advertisement

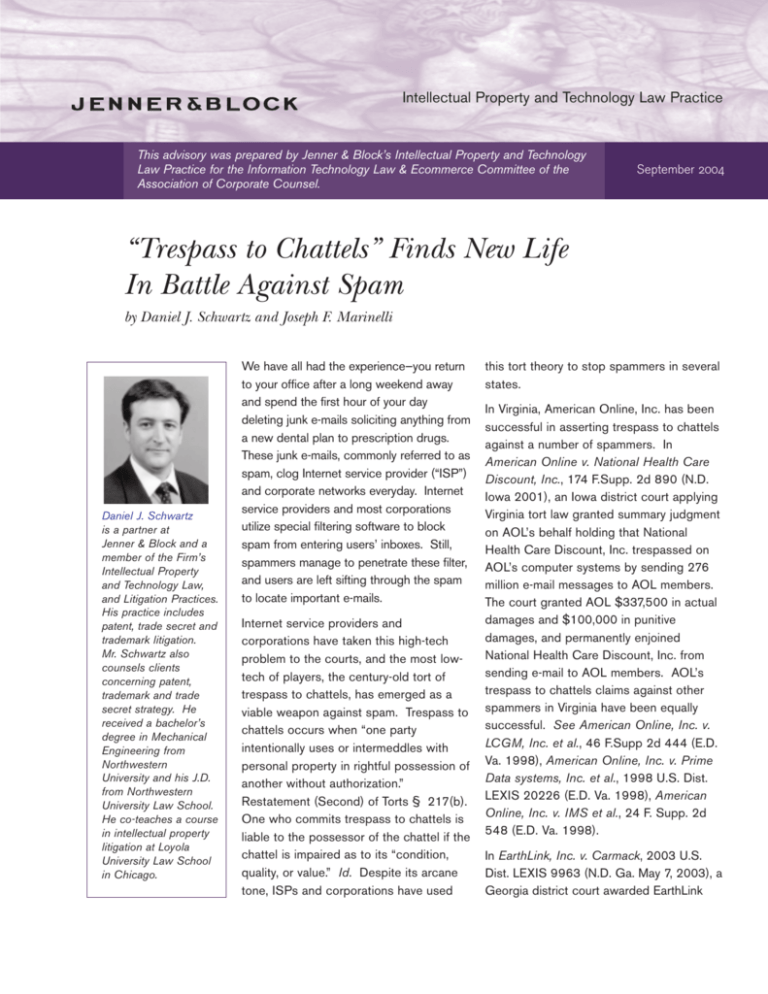

Intellectual Property and Technology Law Practice This advisory was prepared by Jenner & Block’s Intellectual Property and Technology Law Practice for the Information Technology Law & Ecommerce Committee of the Association of Corporate Counsel. September 2004 “Trespass to Chattels” Finds New Life In Battle Against Spam by Daniel J. Schwartz and Joseph F. Marinelli Daniel J. Schwartz is a partner at Jenner & Block and a member of the Firm’s Intellectual Property and Technology Law, and Litigation Practices. His practice includes patent, trade secret and trademark litigation. Mr. Schwartz also counsels clients concerning patent, trademark and trade secret strategy. He received a bachelor’s degree in Mechanical Engineering from Northwestern University and his J.D. from Northwestern University Law School. He co-teaches a course in intellectual property litigation at Loyola University Law School in Chicago. We have all had the experience—you return to your office after a long weekend away and spend the first hour of your day deleting junk e-mails soliciting anything from a new dental plan to prescription drugs. These junk e-mails, commonly referred to as spam, clog Internet service provider (“ISP”) and corporate networks everyday. Internet service providers and most corporations utilize special filtering software to block spam from entering users’ inboxes. Still, spammers manage to penetrate these filter, and users are left sifting through the spam to locate important e-mails. Internet service providers and corporations have taken this high-tech problem to the courts, and the most lowtech of players, the century-old tort of trespass to chattels, has emerged as a viable weapon against spam. Trespass to chattels occurs when “one party intentionally uses or intermeddles with personal property in rightful possession of another without authorization.” Restatement (Second) of Torts § 217(b). One who commits trespass to chattels is liable to the possessor of the chattel if the chattel is impaired as to its “condition, quality, or value.” Id. Despite its arcane tone, ISPs and corporations have used this tort theory to stop spammers in several states. In Virginia, American Online, Inc. has been successful in asserting trespass to chattels against a number of spammers. In American Online v. National Health Care Discount, Inc., 174 F.Supp. 2d 890 (N.D. Iowa 2001), an Iowa district court applying Virginia tort law granted summary judgment on AOL’s behalf holding that National Health Care Discount, Inc. trespassed on AOL’s computer systems by sending 276 million e-mail messages to AOL members. The court granted AOL $337,500 in actual damages and $100,000 in punitive damages, and permanently enjoined National Health Care Discount, Inc. from sending e-mail to AOL members. AOL’s trespass to chattels claims against other spammers in Virginia have been equally successful. See American Online, Inc. v. LCGM, Inc. et al., 46 F.Supp 2d 444 (E.D. Va. 1998), American Online, Inc. v. Prime Data systems, Inc. et al., 1998 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 20226 (E.D. Va. 1998), American Online, Inc. v. IMS et al., 24 F. Supp. 2d 548 (E.D. Va. 1998). In EarthLink, Inc. v. Carmack, 2003 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 9963 (N.D. Ga. May 7, 2003), a Georgia district court awarded EarthLink Joseph F. Marinelli is an associate at Jenner & Block and a member of the Firm’s Intellectual Property and Technology Law Practice. His practice focuses on patent and trademark litigation and prosecution, licensing, and intellectual property counseling. He is a registered U.S. patent attorney. He received his bachelor’s degree in Mechanical Engineering from Purdue University in 1996 and his J.D. from the University of Wisconsin. over $16 million in actual and punitive damages against Howard Carmack for trespass to chattels and violations of other state and federal laws. Carmack engaged in a massive spamming campaign, sending an estimated 857.5 million e-mails, which the court deemed as trespass to EarthLink’s service provider system. The court stated that the substantial award was “to serve a clear message and warning to Carmack and all other similarly-situated wrongdoers that such crime and misconduct will not be tolerated.” Spam as trespass to chattels has been recognized by courts in New York and Ohio as well. In Tyco International (US) Inc. v. Doe, 2003 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 25136 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 29, 2003), Tyco was awarded only $1 in compensatory damages, but also awarded $10,000 in punitive damages by a New York district court against an individual who had attempted to overload Tyco’s e-mail server with 30,000 e-mail messages. The compensatory damage award was nominal because Tyco failed to adequately set forth its actual losses. In CompuServe Inc. v. Cyber Promotions, Inc., et al., 962 F. Supp. 1015 (S.D. Ohio 1997) an Ohio district court granted CompuServe a preliminary injunction against spammers who sent e-mails to CompuServe subscribers. The court found that even though CompuServe’s servers were not physically damaged, their value was diminished by the spam which consumed disk space and processing capacity that would have otherwise been available to CompuServe’s subscribers. The court found that even though CompuServe’s e-mail service allows subscribers to receive messages from anyone on the Internet, the spammers were specifically warned against using CompuServe’s equipment to send their spam messages. While trespass to chattels has been successfully asserted in several spam cases, at least one court has denied the claim. In Intel Corp. v. Hamidi, 30 Cal.4th 1342 (Cal. 2003), the California Supreme Court held that under California law, the tort of trespass to chattels did not encompass an electronic communication that neither damaged the recipient computer system nor impaired its functioning. The court in Hamidi did not rule out trespass to chattels altogether as a cause of action. It simply illustrated its boundaries and found that Intel was outside those boundaries. In that case, Hamidi, a former employee of Intel, sent six different e-mail messages, each to as many as 35,000 Intel employees over a period of two years. The e-mails criticized Intel’s employment practices, warned recipient employees of the dangers those practices posed to their careers and suggested employees consider moving to other companies. Hamidi breached no computer security barriers in order to send the e-mails, and he offered to, and did, remove from his mailing list any recipient who so requested. Intel’s efforts at blocking the transmission of the messages were only partly successful. Intel demanded that Hamidi stop sending the e-mails, but Hamidi persisted. The California Supreme Court ruled that without any evidence that Hamidi’s actions caused or threatened to cause damage to Intel’s computer system, Intel was not entitled to an injunction as a matter of law. Looking to earlier California law and the Restatement (Second) of Torts § 218, the court stated that trespass to chattels required some injury or damage occur to the property. An e-mail that neither damages the recipient computer system nor impairs its functioning is not a trespass because such an e-mail does not interfere with the possessor’s use or possession of the personal property itself. Analyzing the facts under this framework, the court found that there was no evidence indicating that Intel’s computer infrastructure or software was actually damaged or even threatened to be damaged. Intel was not 2 dispossessed of its computers. Hamidi’s messages did not prevent Intel from using its computers for any appreciable length of time. Intel also failed to prove that its system was slowed by the influx of Hamidi’s messages or that the messages imposed any marginal operation cost on Intel. The court distinguished Intel’s situation from those cases discussed above like CompuServe, Inc. v. Cyber Promotions, Inc. in which spamming was found to be actionable trespass. In each of those spamming cases, the plaintiff showed some interference, or threat of interference, with the efficient functioning of its computer system. Compuserve, for example, presented evidence that the defendant’s mass e-mails placed a “tremendous burden” on CompuServe’s equipment by using disk space and draining processing power, leaving those resources unavailable for subscribers. The burden on Intel’s computer system caused by Hamidi’s e-mails did not in the court’s mind measure up to the burden or threat of burden proven in cases like CompuServe. The court recognized that although Hamidi sent thousands of e-mails, the burden on Intel’s computer system was incomparable to the burden caused by spam to an ISP like CompuServe. While trespass to chattels is a formidable weapon for ISP’s and corporations against spam, Hamidi reminds us that it has its boundaries. The one thing Hamidi makes clear — before deciding to bring a trespass to chattels claim, a party must consider the evidence of damage or impairment inflicted by a mass e-mail campaign and how to present that evidence to the court. For more information, please contact any of the following Jenner & Block attorneys: Raymond N. Nimrod Adam Petravicius Daniel J. Schwartz rnimrod@jenner.com adamp@jenner.com djschwartz@jenner.com All attorneys may be contacted by phone at 312 222-9350 ©Copyright 2004 Jenner & Block LLP. Jenner & Block is an Illinois Limited Liability Partnership including professional corporations. This publication is not intended to provide legal advice but to provide information on legal matters and Firm news of interest to our clients and colleagues. Readers should seek specific legal advice before taking any action with respect to matters mentioned in this publication. Under professional rules, this publication may be considered advertising material; the attorney responsible for this publication is Daniel J. Schwartz. Cover image from the Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States. 3