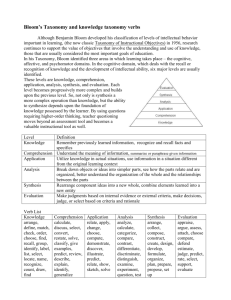

Bloom's Levels of Cognitive Skills

Bloom’s Levels of Cognitive Skills

. . . More subtle distinctions can be made among types of cognitive skills, and these are important because they are what we are most concerned with in education. Probably the most famous instance of classifying cognitive skills can be found in Bloom’s taxonomy. He established six ascending levels of thinking: Knowledge, Comprehension,

Application, Analysis, Synthesis and Evaluation.

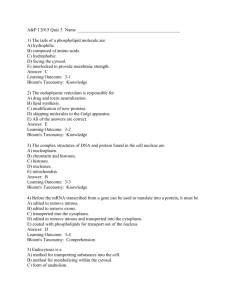

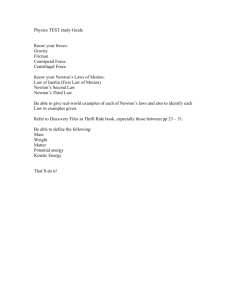

Knowledge is the lowest level of cognition, and it involves merely remembering factual material. Although knowledge is important, it may not be significant in and of itself. That is, knowledge is valuable mainly insofar as you can use it to think in more profound ways. Knowledge gains its importance primarily because it may underlie the other five types of cognition. Thus, when we give students lessons that involve memorization of facts, we should be sure not to stop there. We need to take them to other levels as well. When we access whether someone has gained knowledge, we usually do so by having them recite facts, list them, identify the correct response, and so on. For example, we might ask students whose three laws of motion underlie much of classical physics (Sir Isaac Newton).

The second level, Comprehension, takes us another step. Certainly, we have all known people who can support facts without convincing us that they really understand what they are talking about. At the Comprehension level, we are checking for understanding. We might do this by asking students to paraphrase a theory rather than simply recite it. For example, we could ask them to explain what Newton’s third law of motion means. Certainly this is more valuable than just knowing disconnected facts, like

Newton’s birthplace, the date of his death, or how old he was when he “discovered” gravity.

Application is the third level of cognition in Bloom’s taxonomy. At this level, learners can take what they already know and use it in some way. For example, Newton’s third law states that F=ma, which means force equals mass times acceleration. It is relatively easy for most of us to memorize the formula and its verbal equivalent

(Knowledge). It is a bit more difficult for many of us to describe in our own words what it means (Comprehension). Even harder is to use the formula to solve a real-world physics problem (Application). Clearly, to assess student’s ability to apply what they know, we need to assign tasks that require them to actually solve problems, complete challenging projects, and so on.

Next in Bloom’s taxonomy is Analysis. This skill is more complex still and involves taking an object, a process, or a situation and breaking it down into its constituent elements. For example, faced with a new piece of hardware, an electronics engineer might study its design to figure out what it does and how it works. A scientist can analyze a chemical by literally breaking it into its elements. A historian might analyze the causes of the American Revolution by examining specific aspects of the historical experience. This is not a skill that comes automatically when you know, comprehend, and apply a topic. It takes a student a step beyond those levels of learning.

Some of the thinking processes involved in an analysis might include deduction, induction, generalization, specification, comparison and prediction. When Sir Isaac

Newton formulated his third law of motion, he had to analyze which factors most affected objects in motion, and he came up with mass and acceleration as the two that contributed to the force imparted by moving objects.

The next level, Synthesis, is a mirror image of Analysis. Instead of breaking things down into their constituent elements, with Synthesis we are building them back up.

Synthesis is the ability to put back together to form new ideas, new theories, or new creations. Often it is a design process. An architect might examine the various needs, opportunities, and constraints of the situation and address them in the design of a building that has never been seen before. Or a teacher takes ideas from several different sources to create a lesson that grabs students’ attention and makes that day’s work special. Newton was able to synthesize what was known about the force with which objects move into a formula that established the relationship between the critical variables (F=ma).

Finally the sixth level of Bloom’s taxonomy, Evaluation, involves intelligent critiquing of a product, a process, or a theory. It may rely upon any of the five types of cognition. To make a reasoned and accurate judgment, one may need to have knowledge, comprehend the situation, be able to apply skills and knowledge, analyze the situation and synthesize your ideas. Otherwise, the evaluation is likely to be ill-informed and mere opinion. By Evaluation, Bloom meant an assessment by an expert, not the uninformed opinion of a novice. For example, Einstein evaluated the Newton’s formulations about the universe and knew that his laws did not fully explain all phenomena. Einstein’s theory of relativity was developed to explain aspects of physics that Newton’s laws did not account for.

Why are we telling you all this? We believe that good teaching requires us to push students further up through the progression represented by Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Merely teaching facts and Knowledge isn’t enough.

Comprehension is better, but moving from here to Application is even better. As students progress, they should acquire skills in Analysis, Synthesis, and Evaluation as well.

Similarly, if the vast array of instructional technologies that we now have at our disposal, including the World Wide Web, is used primarily for fact finding, then we have not made good use of them. However, if we incorporate the use of these technologies into lessons that require higher levels of thinking, then we can improve instruction considerably.

To summarize, there is little doubt that the Web can be a tremendous source of educational materials and experiences. But we all know that it is not enough for us merely to point students to a networked computer and tell them to find important information. Students deserve well-constructed lesson plans, engaging them in important tasks that could benefit from the use of Web resources. When the Web is harnessed to a powerful teaching strategy, it can have a major effect on the teaching and learning process and on the achievement of students.

Tiene, D. & Ingram, A. (2001). Exploring current issues in educational technology.

New York, NY, McGraw-Hill. Pg 58-90