Legal Defenses to Foreclosure

advertisement

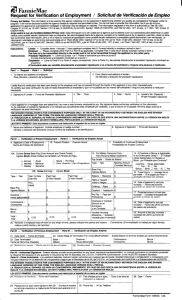

Page 1 LEXSTAT 1-13 DEBTOR-CREDITOR LAW § 13.04 Debtor-Creditor Law Copyright 2009, Matthew Bender & Company, Inc., a member of the LexisNexis Group. PART I Consumer Credit CHAPTER 13 Foreclosure Defense 1-13 Debtor-Creditor Law § 13.04 § 13.04 Legal Defenses to Foreclosure: Procedural Defenses [1] Introduction Before a legally valid foreclosure can take place, there must be a valid mortgage between the parties, a default by the borrower, proper foreclosure procedure, and no cure (where permitted) or redemption by the borrower. The procedure by which procedural challenges can be raised will depend on the method of foreclosure used. If the foreclosure is by judicial process, the homeowner/borrower will have the opportunity to raise defenses and counterclaims to the foreclosure in his or her answer to the foreclosure complaint. A trial will then be held to resolve the claims and counterclaims. With the more common foreclosure by power of sale, however, the foreclosure takes place entirely outside the judicial process. There is no court hearing, no opportunity to raise defenses or counterclaims, no judgement or decision by a court. Thus, to contest a power of sale foreclosure, the homeowner must file an affirmative action to raise these claims and enjoin the foreclosure. This action should be accompanied by a motion for a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction to prevent a foreclosure sale while the homeowner's claims are being litigated. In most states, the posting of a bond is a prerequisite to a temporary restraining order or preliminary injunction. Courts in most jurisdictions may waive this requirement, however, in appropriate circumstances, including indigence. Often the foreclosure is imminent when the homeowner first seeks legal advice, so the advocate must work very quickly to prevent the foreclosure. One potential problem that must be considered is whether the statutes of limitations governing some of these claims bars their assertion where the foreclosure is taking place many years after the original transaction. Whether the foreclosure is by judicial or non-judicial process, sometimes filing a bankruptcy petition is the easiest way to stop an imminent foreclosure and allow the homeowner time to initiate these claims.n1 Substantive and procedural defenses are not waived when a homeowner files bankruptcy. In most jurisdictions, foreclosures are seldom contested by the homeowner. As a result, lenders are often careless about complying with procedural foreclosure requirements, such as the proper and timely service of notice, service on the proper parties, or advertisement in the appropriate place and manner. Practitioners who represent homeowners in foreclosures have found that statutory requirements are not met in many cases. By Page 2 1-13 Debtor-Creditor Law § 13.04 raising a lack of compliance, the homeowner can force the lender to start the foreclosure process over again, or at least to correct the defect, providing the homeowner with additional time to arrange a workout refinancing or a private sale. Because foreclosure is such a harsh remedy, some courts take the position that strict compliance with statutory procedure, and the terms of the mortgage, is required before the foreclosure is permitted. Failure to strictly comply with statutory requirements can be a defense to foreclosure. [2] Default: Waiver and Estoppel While the provisions regarding default and acceleration in the contract documents should be checked for errors or ambiguities, almost all mortgages provide that the failure to pay any installment on its due date is a default which entitles the lender to accelerate the balance of the debt without notice to the homeowner. Some states, however, require that a notice be sent to the borrower indicating the lender's intent to accelerate and providing the borrower an opportunity to cure the default.n2 Some courts have refused to enforce an acceleration provision strictly where the lender has previously accepted late payments from the homeowner and has not insisted on timely future payments.n3 These courts generally hold that the acceptance of late payments by the lender modifies or waives the strict acceleration provisions or stops the lender from strictly enforcing the acceleration provisions. Thus, where there has been an acceleration without notice and subsequent foreclosure, the homeowner may be entitled to have the foreclosure dismissed and be given the opportunity to make timely future payments on the mortgage after notice that late payments will no longer be accepted. A pattern of acceptance of late payments at least creates a factual question as to whether a new agreement had been created. Likewise with accepting partial payments. Some mortgages contain a provision that a waiver of any breach shall not constitute a waiver of any other or subsequent breach or default. Most courts, however, have found such clauses do not bar the borrower from claiming waiver or estoppel. Estoppel may also provide a defense where a lender has agreed to delay foreclosure while the borrower attempts to refinance or to catch up payments, and the borrowers have relied to their detriment on the lender's promise. [a] Real Party in Interest in a Judicial Proceeding State law and rules of civil procedure determine who is a real party in interest and therefore has standing to bring a foreclosure action. The real party in interest is generally the entity that possesses the right sought to be enforced.n4 The question of standing, and a party's right to invoke the jurisdiction of the court, typically becomes an issue when the foreclosing entity was not properly assigned the note and mortgage, or the true holder of the loan is in doubt.n5 In that instance, courts often require proof of assignment of both the note and the mortgage to verify the identity of the holder. Challenging a lender's standing to bring a foreclosure action is a means of temporarily delaying the proceeding as the common law or rules may allow for substitution of the real party in interest.n6 [i] Proper Assignment of Mortgage Without a valid mortgage, a holder of the note has no lien on the property and generally can only institute a collection action, not foreclose on the home.n7 Of course, a successful collection action might give rise to a judgment lien, so defeating the mortgage and not the note may only delay the inevitable if the property can not be protected by a state homestead exemption. Page 3 1-13 Debtor-Creditor Law § 13.04 The statute of frauds requires that any interest in real estate be in writing.n8 Mortgages are now widely considered to create an interest in real estate.n9 Transferring the interest created by a mortgage via assignment should also be covered by the statute of frauds.n10 Using the statute of frauds to defeat a foreclosure action may be easiest when there is no writing transferring either the note or the mortgage to the foreclosing entity. Practitioners should remember that in many jurisdictions, the statute of frauds can be waived, either by failure to plead or failure to object to parole testimony.n11 Courts, primarily in Ohio, have dismissed foreclosure cases brought by assignees when the assignees could not produce a written assignment.n12 The decisions in Ohio are based in part on a requirement in Ohio's law that assignments of mortgages be recorded.n13 Several courts in other states have barred borrowers from asserting the failure of the assignment to comply with the statute of frauds primarily because they find that the borrower is not a third party beneficiary of the assignment contract.n14 As a general rule, only the parties to the contract transferring the interest in land are able to assert a defense of the statute of frauds.n15 This of course overlooks much of the reason for the statute of frauds: to prevent fraud, to protect title to land, and to prevent multiple claims. Borrowers in today's world of securitization, where mortgages are sold often and early, with correspondingly frequent false claimsn16 have reason to demand that any foreclosing entity demonstrate the validity of the documents relied on to assert the claim. [ii] Standing of Servicers to Foreclose Most mortgage loans are pooled and sold to investors on the secondary market. Mortgage originators retain the right to service the loans they sell to permanent investors. This includes collecting payments, maintaining all necessary accounts (including escrow accounts for taxes and insurance), making necessary disbursements, and forwarding the payments to loan investors. Investors such as Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae enter into contracts with servicers to administer the mortgages which they hold. Under Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae guidelines the servicer does not retain an interest in the mortgage or note. The original of any note sold to the investor must be endorsed in blank and delivered to the investor's document custodian.n17 The servicer is assigned the mortgage.n18 However, the servicer is then required to assign the mortgage to the investor, but this assignment is unrecorded.n19 Thereafter the servicer will be the mortgagee of record to ensure that legal notices related to the property are sent to it. [iii] Challenging a Servicer's Standing to Foreclose When a foreclosure action is initiated in the servicer's name, the servicers' standing to bring a foreclosure action depends mainly on state statute and case law. In securitized transactions, it is common for the servicer to file the foreclosure action though an investor or trust is the actual holder of the note and mortgage.n20 Borrowers are most successful in challenging a servicer's standing where state law clearly defines the holder of the note and mortgage as the real party in interest. Some courts have allowed a servicer to file a foreclosure action in its own name when the servicer's agreement with the holder gives the servicer a right to collect and foreclose on the mortgage.n21 Moreover, servicers and lenders often file affidavits from company executives asserting an ownership interest in the loan being foreclosed without providing proper documentation. The failure to produce sufficient evidence documenting the foreclosing entity's interest in the note and mortgage may necessitate a dismissal or delay in the proceedings. [iv] Standing of Mortgage Electronic Registration System to Foreclose The Mortgage Electronic Registration System (MERS)n22 is an electronic registry and clearinghouse established to track ownership and servicing rights in mortgages. Once a loan is assigned to MERS, all subsequent Page 4 1-13 Debtor-Creditor Law § 13.04 assignments will not be recorded in public records. The company will then internally track all changes of ownership, servicing rights, corporate names and mergers. MERS can become mortgagee of record in two ways. For a newly originated loan, a mortgage or deed of trust is prepared with MERS named as the nominee for the lender. MERS as nominee for the lender has been approved by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Ginnie Mae, FHA, and the VA. A lender may also execute an assignment to MERS immediately after closing. Unlike servicers which have an economic interest in servicing the debt, sufficient to confer standing in some jurisdictions, MERS has no beneficial interest in the mortgage in its role as nominee for the holder. MERS does not become the holder of the promissory note that represents the loans.n23 In most jurisdictions, however, MERS forecloses on the loan in its own name or assigns the mortgage to a servicer.n24 MERS has asserted that as the lender's nominee it has the right to foreclose in its own name. A borrower is most successful in challenging this assertion in jurisdictions where the holder of the promissory note is an indispensable party.n25 [b] Other Procedural Defenses Procedural defenses to foreclosure vary from state to state, and can only be determined by reference to state statutes and case law. In general, in states which require a judicial proceeding to foreclose, service of process and other procedural requirements must be met. Foreclosure pleadings may be subject to rules set by case law or rule. Similarly, rules may require that relevant documents be attached to the complaint. Failure to comply may be grounds to object to foreclosure or to move for dismissal, resulting in temporary delays.n26 Although a lender's failure to comply with statutory notice requirements may be a defense to foreclosure,n27 actual notice is generally not required: compliance with statutory notice requirements will usually be sufficient, even where the homeowner can prove that he or she did not receive the notice.n28 [3] Deed of Trust: Trustee Obligations In some jurisdictions, a deed of trust is used as security for a loan, instead of a mortgage. Although there is little practical difference between the two, because a deed of trust is held by a trustee who has an independent duty to protect the rights of the borrower (as well as the lender), borrowers in foreclosure under a deed of trust may be able to raise breach of the trustee's duty as a defense to a foreclosure sale or, after foreclosure, when seeking to set aside a sale. In most jurisdictions "a trustee under a deed of trust owes fiduciary duties both to the lender and to the borrower."n29 Because of her fiduciary relationship, the trustee must be "scrupulously fair and impartial" in carrying out these duties, including the foreclosure sale.n30 The trustee must comply strictly with the terms of the power of sale and with the statute. Failure to comply with statutory requirements may subject the trustee to liability for wrongful foreclosure and may constitute grounds to set aside the sale.n31 In addition, if the trustee has actual knowledge of anything which should legally prevent the foreclosure, she may have a duty to investigate.n32 If the trustee has any potential conflict of interest in acting as trustee, she must disclose this fact or will be required to prove that she was faithful to her duties.n33 Finally, selling the property at a price that is shockingly low may amount to a breach of the trustee's duty,n34 though courts usually look for some irregularity or unfairness in addition to a low price.n35 [4] Default: Enforceability of Due on Sale Contract Provisions Page 5 1-13 Debtor-Creditor Law § 13.04 [a] Overview Due on sale clauses are common contract provisions which give a lender the option to immediately call due, or accelerate, a real-estate secured loan when the borrower sells or transfers all or part of the security to a third party.n36 Almost all consumer mortgage loans contain such a provision in the loan note and/or mortgage. Many lenders seek to enforce this right (which can lead to foreclosure proceedings) even when the transfer is between family members or in the probate process upon death of the debtor. The enforceability of such clauses now is largely a matter of federal law, since state common law or statutory limits on the enforceability of due on sale clauses have been for the most part preempted by the Garn-St. Germain Depository Institutions Act of 1982 ("DIA" or "the Act"),n37 which makes such clauses generally enforceable. DIA applies to any lender, which is defined to include individuals, state and federal banks, state and federal credit unions, and finance companies,n38 and every loan, mortgage, advance, or credit sale secured by a lien on real property.n39 The Act provides that notwithstanding state law, the exercise of a due on sale clause by a lender is governed exclusively by the terms of the contract, subject only to the limitations contained in the Act. Most importantly, DIA prohibits the exercise of due on sale rights with respect to certain nonsubstantive or nonsale transactions, including intra-family transfers.n40 DIA also allowed states the opportunity to maintain some restrictions with respect to some loans. Michigan, New Mexico, and Utah exercised the right to continue state restrictions. In addition, the Act makes clear that it does not prohibit mortgage assumption. In fact, it specifically encourages lenders to permit an assumption of a mortgage, either at the contract rate of interest or at a rate between the contract rate and the market rate.n41 [b] Federal Exemptions Under DIA and Office of Thrift Supervision ("OTS") regulations issued pursuant to DIA, valid due on sale contract provisions are enforceable by lenders, but nine specific exemptions prevent the enforcement of the due on sale clause.n42 These federal regulations and their preemption of state law can be raised defensively to prevent foreclosure if one of these exemptions applies. [c] Intra-Family Transfers The federal law aims to protect intra-family transfers from triggering acceleration. These include transfers to the borrower's relative on the borrower's death, transfers to the borrower's children and spouse, and transfers resulting from a marriage dissolution or property settlement. [d] Lender Waiver by Agreement In all states other than Michigan, New Mexico, and Utah, if, before a transfer occurs, a lender and the proposed transferee enter into a written agreement for the latter to assume the loan, the lender waives its option to exercise a due on sale clause with respect to that transfer.n43 [e] Contractual Limits on Due on Sale Clauses Are Not Preempted With respect to all loans, contractual limits on the lender's right to accelerate still apply. Both parties are bound by the contract and the statute does not change that. [f] Prepayment Fees and Loan Acceleration Page 6 1-13 Debtor-Creditor Law § 13.04 Some mortgages include provisions which require a borrower to pay a penalty if the loan is repaid before it is legally due. The federal regulations prohibit the charging of such fees when the lender seeks to enforce a due on sale clause by written demand or formal proceedings on loans secured by the borrower's home.n44 [5] Other Procedural Defenses Other examples of successful procedural defenses may include the failure of the lender to introduce the original note in the foreclosure proceeding, the misjoinder of a claim for personal liability on the mortgage note in the foreclosure proceeding, failure to join a necessary party, the improper or ineffective assignment of the mortgage, or the failure to comply with statutory notice requirements. Legal Topics: For related research and practice materials, see the following legal topics: Real Property LawFinancingMortgages & Other Security InstrumentsForeclosuresGeneral OverviewReal Property LawFinancingMortgages & Other Security InstrumentsForeclosuresJudicial ForeclosuresReal Property LawFinancingMortgages & Other Security InstrumentsForeclosuresPrivate Power-of-Sale ForeclosureReal Property LawFinancingMortgages & Other Security InstrumentsFormalitiesReal Property LawFinancingMortgages & Other Security InstrumentsTransfersDue-on-Sale Clauses FOOTNOTES: (n1)Footnote 1. See Collier Consumer Bankruptcy Practice Guide Ch. 4 (Matthew Bender), for discussion of using bankruptcy to stop a foreclosure. (n2)Footnote 2. See Citimortgage, Inc. v. Lovelett, 2001 Conn. Super. LEXIS 581 (Conn. Super. Ct. Feb. 27, 2001) (notice of default may be required in order to accelerate and foreclose even when the mortgage note does not require such notice); Sarasota, Inc. v. Ballew, 2001 Tex. App. LEXIS 1262 (Tex. App. Feb. 28, 2001) (note and deed of trust do not require automatic acceleration of note upon default and mortgagee who did not clearly and unequivocally express intent to accelerate the note cannot foreclose). (n3)Footnote 3. See, e.g., Smith v. General Fin. Corp., 243 Ga. 500, 255 S.E.2d 14 (1979) ; Meehan v. Cable, 135 N.C. App. 715, 523 S.E.2d 419 (1999) (note holder who repeatedly accepted late payments waived the right to accelerate debt without first notifying mortgagor that prompt payment would be expected in the future). But see Ocwen Fed. Bank, FSB v. Weinberg, 1999 Conn. Super. LEXIS 2204 (Conn. Super. Ct. Aug. 11, 1999) (where mortgage expressly contains non-waiver clause, mortgagee did not waive right to accelerate mortgage by accepting late payment). (n4)Footnote 4. See First Union National Bank v. Hufford, 146 Ohio App. 3d 673, 767 N.E.2d 1206 (Ohio Ct. App. 2001) (a real party in interest is one who is directly benefited or injured by the outcome of the case). (n5)Footnote 5. See, e.g., Harmony Homes v. United States ex rel. Small Bus. Admin., 936 F. Supp. 907 (M.D. Fla. 1996) (lender who assigned away interest in property was not the proper party to file suit to foreclose a mortgage); Laing v. Gainey Builders, Inc., 184 So. 2d 897 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 1966) ; Redding v. Gibbs, 280 N.W.2d 53 (Neb. 1979) ; First Union Nat'l Bank v. Hufford, 767 N.E.2d 1206 (Ohio 2001) ; Washington Mutual Bank v. Green, 156 Ohio App. 3d 461, 806 N.E.2d 604 (Ohio Ct. App. 2004) (question of fact which existed as whether the lender was owner and holder of note and mortgage, precluding summary judgment); Kramer v. Millott, 1994 Ohio App. LEXIS 4454 (Ohio Ct. App. Sept. 23, 1994) . (n6)Footnote 6. See Div. 2003) . East Coast Properties v. Galang, 308 A.D.2d 431, 765 N.Y.S.2d 46 (N.Y. App. Page 7 1-13 Debtor-Creditor Law § 13.04 (n7)Footnote 7. But see Conn. Gen. Stat. § 49-17 (permitting foreclosure where the note is validly transferred even if the mortgage is not assigned); U.C.C. § 9-203(g) (right to foreclose belongs in equity to owner of the debt). (n8)Footnote 8. The Statute of Frauds was enacted in English law in 1677 and carried over, either by statute or common law, to all of the states except Louisiana. Restatement (Second) of Contracts ch. 5, statutory n. (1981) (listing the corresponding state statutes). (n9)Footnote 9. See, e.g., Manir Properties v. Resolution Trust Corp., 1993 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 13582 (E.D. Pa. Sept. 27, 1993) (explaining that Pennsylvania common law treated mortgages as a "chose in action" and therefore not subject to the statute of frauds but that Pennsylvania law now clearly treats mortgages as interests in real property). (n10)Footnote 10. Lininger v. Sonenblick, 532 P.2d 538 (Ariz. Ct. App. 1975) (holding, without discussion, that assignments of mortgages are covered by the statute of frauds). But see Levy v. McGill, 137 Fed. Appx. 613 (5th Cir. 2004) (statute of frauds may not cover assignments of mortgages); Love v. Irwin, 228 F.2d 501 (5th Cir. 1956) (holding in dicta that assignment of mortgages may not be covered by the statute of frauds). (n11)Footnote 11. Gramatan Home Investors Corp. v. Whittemore, 518 A.2d 32 (Vt. 1986) (overturning dismissal of foreclosure action for assignee's failure to produce documentary evidence of assignment because borrowers waived statute of frauds defense when they did not object to testimony of the assignment). But see Becker v. Dramin, 6 Conn. Supp. 33 (Conn. Super. Ct. 1938) (mortgage follows note, so assignment of mortgage is not covered by the statute of frauds, provided there is a valid transfer of the note). Cf. Levy v. McGill, 137 Fed. Appx. 613 (5th Cir. 2004) (asset purchase agreement, in lieu of assignment, was definite enough and did not need to be delivered to transfer trust deed). (n12)Footnote 12. See In re Foreclosure Cases, 2007 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 84011 (N.D. Ohio Oct. 31, 2007) ; KeyBank N.A. v. Estate of Wright, 2006 Ohio 4643 (Ohio Ct. App., Lucas County Sept. 1, 2006) (denying Countrywide leave to intervene and assert prior lien in mortgage foreclosure action since it had not produced or recorded an assignment of the prior mortgage). Cf. Everhome Mortg. Co. v. Rowland, 2008 Ohio 1282 (Ohio Ct. App., Franklin County Mar. 20, 2008) (reversing summary judgment in favor of assignee in foreclosure action since assignee failed to demonstrate it had an interest in either the note or the mortgage). (n13)Footnote 13. See In re Foreclosure Cases, 2007 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 84011 (N.D. Ohio Oct. 31, 2007) . Cf. In re Dimmings, 386 B.R. 199 (Bankr. N.D. Ohio 2008) (denying motion for relief from stay in part because original creditor and subsequent assignee failed to record mortgage). But cf. Martin v. Select Portfolio Serving Holding Corp., 2008 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 16088 (S.D. Ohio Mar. 1, 2008) (failure to record or produce assignment until requested by plaintiff in FDCPA action does not invalidate assignment). (n14)Footnote 14. See Countrywide Home Loans, Inc. v. Brown, 223 Fed. Appx. 13 (2d Cir. 2007) (borrower cannot raise of frauds defense because the defense is "personal" to the assignor); Austin v. Countrywide Homes Loans, 261 S.W.3d 68 (Tex. App. Houston 1st Dist. 2008) (homeowner was not a party to the assignment and so has no right to invoke the statute of frauds with respect to the assignment). Cf. Levy v. McGill, 137 Fed. Appx. 613 (5th Cir. 2004) (statute of frauds may not cover assignments and asset purchase agreement, in lieu of assignment, was definite enough and did not need to be delivered to transfer trust deed); Conradt v. Lepper, 81 P. 307 (Wyo. 1905) (borrower could not assert illegal assignment of mortgage as a defense to foreclosure if the underlying mortgage was valid). (n15)Footnote 15. Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 144 (1981). (n16)Footnote 16. See, e.g., Impac Warehouse Lending Group v. Credit Suisse First Boston LLC, 270 Fed. Appx. 570 (9th Cir. Cal. 2008) (litigation by warehouse lender against securitizer and mortgage broker; Page 8 1-13 Debtor-Creditor Law § 13.04 mortgage broker sold same loans to both warehouse lender and securitizers, apparently creating fake documentation for the sale to the warehouse lender). (n17)Footnote 17. See, e.g., Fannie Mae Single Family Servicing Guide, Part IV, Chapter 2, § 204. Notes and other key documents are held on behalf of investors by third-party document custodians which are approved financial institutions, by mortgage servicers, or by the investors themselves. (n18)Footnote 18. See Fannie Mae Single Family Servicing Guide, Part IV, Chapter 4, § 403; Freddie Mac Single-Family Seller/ Servicer Guide § 22.14. (n19)Footnote 19. See Fannie Mae Single Family Servicing Guide, Part IV, Chapter 4, §§ 402, 403. Fannie Mae requires that, for any mortgage not registered with MERS, the mortgage seller prepare an assignment of the mortgage to Fannie Mae; that assignment should not be recorded. If the mortgage seller will not service the loan, Fannie Mae requires a recorded assignment from the seller to the servicer. The note is not endorsed to the servicer. See also Freddie Mac Single-Family Seller/ Servicer Guide § 22.14. (n20)Footnote 20. If the servicer files suit in its own name instead of in the name of the holder, an argument could be made that this is a fraud on the court. On the other hand, if the creditor files suit in the name of the actual holder, it may be the unauthorized practice of law for a servicer to retain counsel to represent the holder. At least one court has come to such a conclusion. In re Morgan, 225 B.R. 290 (Bankr. E.D.N.Y. 1998) . (n21)Footnote 21. Bankers Trust v. 236 Beltway Inv., 865 F. Supp. 1186 (E.D. Va. 1994) (both lender and servicer had standing to sue on mortgage in default); First Nat'l City Bank v. Burton M. Saks Constr. Corp., 70 F.R.D. 417 (D. V.I. 1976) (servicer the proper party under Rule 17(a) when contract with holder gave it the authority to bring a foreclosure action); In re Tainan, 48 B.R. 250 (Bankr. E.D. Pa. 1985) (servicer, in capacity as representative of Fannie Mae for collection purposes, was the party in interest for Rule 17(a) purposes in a relief from stay proceeding). Green Tree Servicing L.L.C. v. Sanders, 2006 WL 2033668 (Ky. Ct. App. July 21, 2006) (under terms of pooling and servicing agreement, servicer became the real party in interest once the loan was automatically assigned to it at the commencement of a foreclosure action). (n22)Footnote 22. MERS' website, www.mersinc.org contains useful information on the company and a state-by-state summary of its recommended foreclosure procedures. (n23)Footnote 23. See Fannie Mae Single Family Servicing Guide, Part IV, Chapter 2, § 204. See also Taylor, Bean & Whitaker Mortgage Corp. v. Brown, 276 Ga. 848, 583 S.E.2d 844 (Ga. 2003) ; Nelson & Whitman, Real Estate Finance Law, § 5.34 (West Group 4th ed. 2002). (n24)Footnote 24. According to Fannie Mae guidelines, when MERS is the mortgagee of record (either as an assignee or as the nominee for the original mortgage), the jurisdiction in which the property is located will determine how foreclosure proceedings are initiated or conducted. In most states the foreclosure attorney should initiate the action in MERS' name. Fannie Mae Single Family Servicing Guide, Part VIII, Chapter 1, § 105. Freddie Mac requires foreclosure in the name of MERS or a transfer of the mortgage from MERS to servicer and foreclosure in the servicer's name. Freddie Mac Single-Family Seller/Servicer Guide, § 66.17. (n25)Footnote 25. Mortgage Elec. Registration Sys. v. Rees, 2003 Conn. Super. LEXIS 2437 (Conn. Super. Ct. Sept. 4, 2003) . (n26)Footnote 26. For a good listing of procedural defenses and case law, see National Consumer Law Center, Foreclosures, § 4.3 (1st ed. 2005 and Supp.). But see Ocwen Fed. Bank v. Harris, 2000 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 16649 (N.D. Ill. Oct. 23, 2000) (assignee did not need lost promissory note to foreclose). See, e.g., Hutchison v. Chase Manhattan Bank, 922 So. 2d 311 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2006) (mortgagor was not served with a summons or named as a party in foreclosure proceedings; he did not receive adequate notice or have an opportunity to be heard in accordance with due process under the state constitution). Page 9 1-13 Debtor-Creditor Law § 13.04 (n27)Footnote 27. Agricola Partners, Inc. v. Parker, 655 So. 2d 967 (Ala. 1995) . See Abdel-Kafi v. Citicorp Mortgage, Inc., 772 A.2d 802 (D.C. 2001) (notice of foreclosure sale was invalid when mortgagee sent notice to the wrong address); Ohio Sav. Bank v. Hawley, 2001 Ohio App. LEXIS 702 (Ohio Ct. App. Feb. 16, 2001) (foreclosure sale vacated when mortgagor did not receive actual notice of the sale; notice by publication was inadequate). See also G.E. Capital Mortgage Servs. v. Baker, 1999 Conn. Super. LEXIS 1791 (Conn. Super. Ct. July 2, 1999) (letter to mortgagor which improperly provided for a thirty-day cure period instead of the sixty days required by the mortgage is a special defense to foreclosure). (n28)Footnote 28. See Mississippi Farm Bureau Ins. Co. v. Coleman, 876 F. Supp. 111 (S.D. Miss. 1995) . (n29)Footnote 29. Perry v. Virginia Mortgage & Inv. Co., 412 A.2d 1194, 1197 (D.C. 1980) (citing S & G Inv. Inc. v. Home Fed. Sav. & Loan Ass'n, 505 F.2d 370, 377 n.21 (D.C. Cir. 1974)) ; see National Life Ins. Co. v. Silverman, 454 F.2d 899 (D.C. Cir. 1971) ; Maynard v. Sutherland, 313 F.2d 560, 565 n.16 (D.C. Cir. 1962) ; Spruill v. Ballard, 58 F.2d 517 (D.C. Cir. 1932) ; Killion v. Bank Midwest, 987 S.W.2d 801, 813 (Mo. Ct. App. 1998) ; Sloop v. London, 219 S.E.2d 502, 504-05 (N.C. 1975) . (n30)Footnote 30. Sheridan v. Perpetual Bldg. Ass'n, 322 F.2d 418, 421 (trustee breached duty by releasing first purchaser at foreclosure sale who had bid higher amount, then selling to second buyer for less, without consulting borrower); Killion v. Bank Midwest, 987 S.W.2d 801, 813 (Mo. Ct. App. 1998) (fiduciary relationship does exist between the trustee and the debtor and creditor; trustee is considered to be the agent of both debtor and creditor and should perform the duties with impartiality and integrity). (n31)Footnote 31. In re Worcester, 811 F.2d 1224 (9th Cir. 1987) (trustee's failure to accurately describe property in notice of sale and in deed was grounds for setting aside sale); Sloop v. London, 219 S.E.2d 502, 505 (N.C. 1975) (trustee's failure to attend sale and his signing of sale "report" before sale occurred were breaches of duty). (n32)Footnote 32. See Killion v. Bank Midwest, 987 S.W.2d 801 (Mo. Ct. App. 1998) (finding no breach of duty, but noting the trustee may proceed without making an investigation unless he has actual knowledge of anything which would legally prevent the foreclosure). But see Lewis v. Jordan Inv., Inc., 725 A.2d 495, 500 (D.C. 1999) ("Absent fraud, misrepresentation, or self-dealing, we do not impose any additional duties upon the trustee."); 2 Baxter Dunaway, The Law of Distressed Real Estate § 17:25 (2003) (no duty to investigate absent unusual circumstances). (n33)Footnote 33. Sheridan v. Perpetual Bldg. Ass'n, 322 F.2d 418, 421 (D.C. Cir. 1963) (because of their close connection with the lender, trustees were not qualified to act as trustees unless borrower, after full and fair disclosure, acquiesced); Lewis v. Jordan Inv., Inc., 725 A.2d 495, 500 (D.C. 1999) ; Perry v. Virginia Mortgage & Inv. Co., 412 A.2d 1194, 1197 (D.C. 1980) ; Mills v. Mutual Bldg. & Loan Ass'n, 216 N.C. 664, 6 S.E.2d 549, 552 (1940) (trustee who both acted as trustee and bid at sale on behalf of creditor breached duty of impartiality). (n34)Footnote 34. Lewis v. Jordan Inv., Inc., 725 A.2d 495, 500 (D.C. 1999) (finding that the foreclosure sale price was not shockingly low); see In re Krohn, 52 P.3d 774, 777, 781 (Ariz. 2002) . (n35)Footnote 35. See § 13.14[4] infra; see also In re Worcester, 811 F.2d 1224, 1232 (9th Cir. 1987) (inadequate price plus irregularity in sale constitute grounds to set aside sale). (n36)Footnote 36. See American Investors, Inc. v. King, 796 So. 2d 955 (Miss. 2001) (lender may foreclose when mortgagor deeded interest to third party without prior written consent of lender). (n37)Footnote 37. 12 U.S.C. § 1701j-3. (n38)Footnote 38. 12 C.F.R. § 591.2(g). (n39)Footnote 39. 12 U.S.C. § 1701j-3(a)(1). Page 10 1-13 Debtor-Creditor Law § 13.04 (n40)Footnote 40. 12 U.S.C. § 1701j-3(d). (n41)Footnote 41. 12 U.S.C. § 1701j-3(b)(3). (n42)Footnote 42. 12 U.S.C. § 1701j-3(d); 12 C.F.R. §§ 591.3-591.5 (1994): 1) the creation of a lien or other encumbrance subordinate to the lender's security instrument which does not relate to the transfer of rights of occupancy, provided that such encumbrance is not created pursuant to a contract for deed; 2) the creation of a purchase money security interest for household appliances; 3) a transfer by devise, descent or operation of law on the death of a joint tenant or tenant by the entirety; 4) the granting of a leasehold interest for three years or less with no option to purchase; 5) a transfer, resulting from the borrower's death, to a relative who will occupy the property; 6) a transfer to the borrower's spouse or children where they will occupy the property; 7) a transfer resulting from a decree of dissolution of marriage, legal separation agreement or incidental property settlement agreement where the transferee becomes the owner and occupier of the property; 8) a transfer into an inter vivos trust in which the borrower is a beneficiary and which does not affect a transfer of occupancy rights, provided that the borrower does not refuse to provide the lender with reasonable means to receive timely notice of a transfer of the beneficial interest or a change in occupancy; 9) any other transfer or disposition described in regulations proscribed by the Federal Home Loan Bank Board. (n43)Footnote 43. 12 C.F.R. § 591.5(b)(4). Lenders may also waive their option to exercise the due on sale clause by accepting payments from the transferee. See Brown v. Powell, 648 N.W.2d 329 (S.D. 2002) (court held that because vendor was aware that purchaser had assigned his interest to attorney while accepting payments on contract from attorney, thus vendor waived non-assignment clause and forfeiture of contract was inequitable). But see Kings Langley, Ltd. v. Federal Dep. Ins. Corp., 108 F.3d 338 (9th Cir. 1996) (table) (text available at 1996 U.S. App. LEXIS 33199 ) (no waiver by acceptance of payments after transfer when lender not aware of transfer and manner of payment designed to conceal transfer); In re Martin, 176 B.R. 675, 676 (Bankr. D. Conn. 1995) (lender does not waive its right to enforce a due on sale provision when it does not specify violation of due on sale provision when it accelerated the mortgage because the lender was not aware of the transfer at the time). (n44)Footnote 44. 12 C.F.R. § 591.5(b)(2).